Spend enough time reading about photography, and you’ll come across the phrase “infinity focus.” It may sound like nonsense – how often do you need to focus on a subject that’s infinitely far away?! – but there are many reasons why focusing at infinity can be useful in photography. In this guide, I’ll introduce infinity focus and explain how to use it as a photographer.

Table of Contents

The Definition of Infinity Focus

At the most basic level, infinity focus is pretty simple. If you manually focus your lens “to infinity,” then any object that’s infinitely far away will be in-focus in your photo.

Of course, even the most distant stars in the night sky aren’t infinitely far away. But lenses have depth of field, so if you set your lens exactly to infinity focus, then you’ll generally get the distant horizon, the moon, the stars, and other very distant objects in-focus.

Many lenses have a focus distance scale that includes the “∞” symbol representing infinity focus. If you turn the focusing ring precisely to ∞, you will have successfully focused at infinity, at least in theory. (Manufacturing tolerances and ambient temperature can affect this slightly.) Here’s one such lens:

Some lenses have a hard stop at infinity focus, and you can’t turn the focusing ring past that. Other lenses let you move the focusing ring past infinity to account for manufacturing tolerances in the lens. (There is no such thing as a subject that’s farther away than infinity, so these focus distances are rarely used otherwise.)

A more technical definition of “infinity focus” is to set a lens’s focal point so that parallel light rays form the image of an infinitely distant object. That definition may help you understand a bit of the physics behind the scenes, but it’s beyond what most photographers care about.

In the next few sections, I’ll be looking at the reasons why a photographer would focus at infinity, plus how to do so.

Why Focus at Infinity?

“Focusing at infinity” is generally done when everything in your photo is far in the distance (at least, everything that you want to be sharp). Astrophotographers are very familiar with the concept of infinity focus, but it can also apply to other types of photography, like landscape, aerial, and cityscape photography.

If you’re standing at an overlook, and there is nothing in the foreground, you can safely set your lens to infinity and expect the entire photo to be in-focus. Even if there is a foreground, you may still decide to focus at infinity if you prioritize the sharpness of the distant object over the foreground.

For example, I took the following photo at infinity focus to maximize the sharpness of the stars, even at the expense of a slightly out-of-focus foreground in the very bottom left corner:

This is much better than focusing in the tiny sliver of foreground at the bottom left and having the mountain and the stars look soft.

Normally, you would not try to focus at infinity if there is an important foreground in the photo. In the photo below, I wanted both the foreground and the background to look sharp. So, I focused roughly in the middleground between the foreground and background. If I had focused at infinity (AKA focused on the distant mountains), the bottom portion of the road would be a bit blurry:

In general, you should reserve infinity focus for times when everything in your photo is pretty far in the distance. There are of course exceptions – maybe you want the foreground to be blurry for a creative effect – but that’s the general rule. (Another exception is if you’re planning to focus stack images; in that case, you might take one photo at infinity focus and one photo focused on the foreground to blend them later.)

Your subject doesn’t need to be infinitely far away – which again, is impossible – for infinity focus to be right for your photo. It’s relevant any time that you don’t have a nearby, important foreground.

How Does Depth of Field Affect Infinity Focus?

Depth of field refers to how much of the area in front of and behind the focal point is in acceptable focus. I say “acceptable” because technically only a single distance, the focal point, is truly in focus.

Your depth of field increases when you use wider focal length lenses, stand further away from your subject, and use a narrower aperture. For more on the subject, consider checking out Elizabeth’s excellent overview of depth field.

On one hand, depth of field does not change the infinity focus point at all. The same spot on your lens will be infinity focus whether you’re at f/1.4, f/16, or anything else (assuming a lens without focus shift issues). Still, depth of field plays a big role in this discussion.

For example, if you’re photographing the Milky Way with a 50mm f/1.4 lens, you will have very limited depth of field, and you’ll need to focus very precisely in order to get sharp stars. Your foreground is probably going to be severely out of focus unless it’s something very far away, like a mountain. On the other hand, you have a lot more leeway if you’re using something like a 14mm f/4 lens to photograph the Milky Way, since it has more depth of field.

In both cases, infinity is still infinity, but the greater depth of field gives you a sharper foreground and allows you to be more relaxed about how far you’ve actually focused. This ties into the next concept I’ll talk about, which is hyperfocal distance.

What is Hyperfocal Distance?

A closely related concept to infinity focus is called “hyperfocal distance.” Spencer already has an in-depth guide to the complexities of hyperfocal distance, but you can get a basic understanding just from the concepts I’ve already covered today.

In practice, hyperfocal distance is the focusing distance that maximizes the sharpness of your photo from near to far. Generally, this means that subjects around infinity focus (like the horizon) will be just as sharp as the closest foreground element.

If you have no foreground to worry about, by all means, set the lens to infinity focus. But if there is a foreground that you want to be sharp, I recommend focusing a bit closer than infinity to get the foreground to look sharper. It will come at the expense of sharpness at infinity, but you can usually account for that by stopping down your aperture a bit.

An easy way to find the hyperfocal distance in any scene is to use Spencer’s double-the-distance focusing method.

How Can You Easily Focus at Infinity?

So far, I’ve talked about all the ways that infinity focus is useful in photography. But how do you actually focus there? Even if your lens has the “∞” mark (and not all of them do), it can be tougher than it looks. There are a few methods to focusing at infinity, and each has its benefits and drawbacks.

Autofocus

The quickest way to focus at infinity is to autofocus on any part of your photo that’s far in the distance. The horizon is usually a good spot to focus, but you could also autofocus on something like the moon.

Most of the time, this will be all you need to do in order to focus at infinity. That said, not all lenses have autofocus. Even if yours does, the autofocus may not work properly in low-light situations, or it may not give you the accuracy that you need for maximum sharpness. A lot of Milky Way photographers avoid autofocus for these reasons.

To increase your success rate with autofocus, I’d suggest aiming at a high-contrast object in the distance and using just one autofocus point. Set single-servo autofocus instead of continuous-servo. And if it’s an important photo, review the picture in-camera at a high magnification to make sure you’ve successfully nailed focus at infinity. If you haven’t, either try again or use manual focus instead.

Manual Focus – Looking at the Lens

If your lens has a focusing scale, you might be able to turn the manual focus ring to the infinity symbol and call it a day. It’s a very fast method. However, it is not always very accurate. Depending on your copy of the lens or even the ambient temperature, the “∞” marker on your lens may not be exactly the same as infinity focus. This won’t always matter, but for very demanding subjects like the stars at night, I wouldn’t recommend this method.

Manual Focus – Magnifying Live View

A more assured way to focus on tricky subjects at infinity, like the Milky Way, is to use live view and focus manually. The idea is to go into live view, magnify the image as far as possible on a bright star, and slowly spin the lens’s focus ring back-and-forth until you’re confident that it’s focused properly. This is a slower method, of course. It also requires a tripod most of the time. But the accuracy makes it a valuable technique if you enjoy astrophotography.

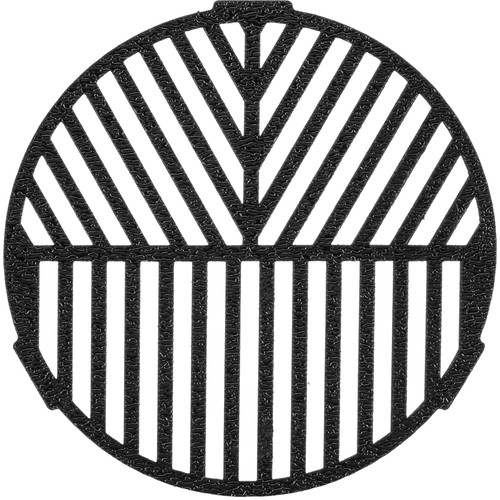

Manual Focus – The Bahtinov Mask

One of the most common scenarios for setting infinity focus involves astrophotography. If you’re a dedicated astrophotographer, it may be worth picking up a Bahtinov mask. This piece of equipment is quite affordable, since it’s just a plastic grid that goes in front of your lens. Once in place, this grid makes it far easier to set focus manually on stars, by creating bright diffraction spikes around them. When you focus and then remove the mask, the stars will remain completely sharp.

Conclusion

Infinity focus is an important concept to landscape photographers, astrophotographers, and others. It also matters when you’re reading about photography, choosing equipment, and learning various concepts. For example, when we review a lens, we always mention whether it has any image quality issues like vignetting that get worse at infinity focus.

While not every situation requires infinity focus, I’m sure you’ll find photos where you want distant objects to be as sharp as possible. That may require focusing at infinity, or it may require focusing at the hyperfocal distance and using a narrower aperture. Either way, now you have the knowledge to make the right decision. Let me know in the comments if you have any more questions about infinity focus!

Alex, some YT macro tutorials suggest putting the focusing lens to infinity, leaving it there, and focusing on the subject by moving the subject or camera as necessary.

Three questions about that-

Why set the lens to infinity first?

My lens has no infinity indicator, how would I know, when shooting macro, when my lens is at infinity?

As I use extension tubes, I presume that “infinity” changes with each change of focal plane – would that be correct?

Many thanks for your anticipated response.

Mike

Hi Mike. That’s odd advice. Unless you’ve got something like focus bellows or other specialty equipment, you won’t be able to get a macro subject in focus if your lens is at infinity. Are they instead advising to focus your lens at a set distance or magnification ratio, like 1:2, then move your camera to adjust the plane of focus? I’ve occasionally heard of that approach.

Something I find helpful after I’ve focused to my satisfaction and turned the lens to Manual: apply a piece of blue painter’s tape to the edge of the focus ring and a bit of the stationary part of the lens. That way I don’t mess up and accidentally change the focus in the dark. It removes easily, or it can be lifted a bit to adjust the focus and then battened down again. I read this hint somewhere, not sure where now, and it works great, for me anyway.

Great article! I’ve noticed that autofocus will change ever so slightly from objects that should be at infinity…ridge line vs. the moon for example. For that reason I double check the most important part of the frame using the Live View method.

Thanks for the article, and if you were only to work out the focusing distance by the numbers on above Otus lens, does it say past 15 meteres is where you reach infinity? Why the markings donot say exactly where about you reach this point?

On most lenses, you reach infinity focus when the marker is at the very center of the “∞” symbol. In the photo of the Otus lens above, the focusing ring is currently set exactly to infinity focus.

(There is no 15 meter focusing mark, because lens focusing scales aren’t linear. And thankfully not! Otherwise, you’d have to spin the focusing ring infinitely many times to reach infinity focus :)

Thanks, I get that but I guess each lens has some distance past which everything becomes infinity in practice, i.e incoming rays in parallel, and was curious if you can figure out this distance from markings but I understand you can not