Maximizing Opportunities

Below I would like to share some very important things to consider when trying to maximize on a rare wildlife opportunity.

It has been a long term dream of mine to have the chance to photograph a great gray owl up close and personal. After nearly ten years of being too late to the scene of reported great gray owls within driving distance of where I live, it finally happened, not once but twice (two owls). Go figure! I suppose I shouldn’t complain, its like a wow sequence of events for me.

So what you have to understand here, is, that the GGO was and probably will remain one of those ‘once in a lifetime photographic’ opportunities for me, so how do I maximize the quality and diversity of the photos I come home with. This event may never happen again like this for me, as you can see, I had been trying for ten years before it happened this time. When you think of that long timeframe, you must understand how important it was for me to come home with something I was proud of, if I didn’t I would be really disappointed in myself.

To those that haven’t had the chance to photograph a GGO up close and personal, I would say that this owl is one of the most friendly and tolerant to humans that I have ever seen in a raptor. It makes for some wonderful photographic chances from a totally wild bird acting and hunting naturally in its temporary environment before it heads back to its home base.

Before I go into details of how I photograph such a raptor, let’s remove the question that almost always comes up with high action up close owl photos. “Did you bait ?” / “Is this owl being baited ?”. The answer for my photos here is “no baiting was involved” and the owl was quite adept at hunting by itself, on many occasions, in fact. I am not stupid, I have seen and heard of others baiting and I am fully aware it happens, but let me tell you, it does not need to happen.

Where I live this is a rare bird event, really rare! The first and very important thing is to find the bird or be told about it early enough upon its arrival to have the chance to photograph it. How does that happen? One of the best ways is to join a birding group or monitor some form of e-bird listing on social media and the web. Birders are very good at finding and reporting rare birds, they also have ethics and bird watching guidelines, so be sure to follow those if you do join a group. For a rare single bird like this, if you are first on the scene, you will have to walk / search the area the bird is being reported in yourself to try and find the bird. If others are already onto it, just look for the huge group of photographers/ birders and you will have found the bird. I was lucky enough to have the bird by myself / in a small group and a very large group (about 70 people), the smaller the group the better your chances for the good stuff.

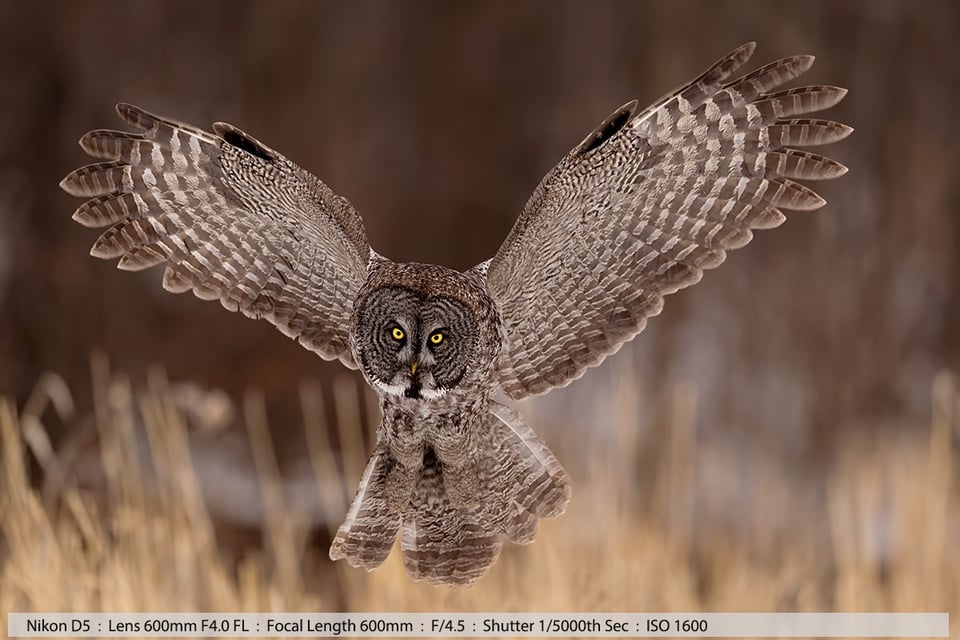

Why did I choose to use mostly a 600mm? Because in my experience raptors/birds generally need longer focal lengths to help fill the frame of what is generally a smaller subject relative to other animals like bears/moose etc. Even though the GGO is the largest owl in North America is still a relatively small subject, its about the size of a bald eagle. I also like the way the 600mm makes the owl fill the frame more on flying shots and the bokeh it produces to help separate the subject from the background. I did use the 200-400mm F4 lens several times because of how friendly this owl was and we could get relatively close to it at times.

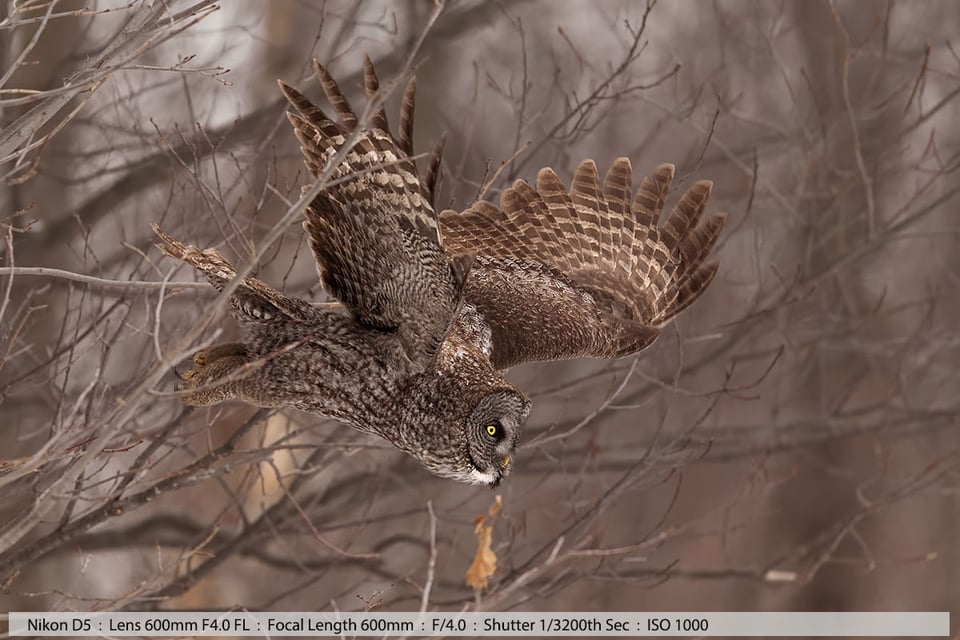

You have to be wise with your lens choice, you need to be ready for hours of boring sitting/sleeping shots that suddenly turn into fast-flying, high activity shots. You have to be able to handle all the situations fluently, panning on the bird in flight, holding steady for sitting shots, being immediately ready if the bird transitions from sleep mode to hunt mode. Maybe you can only handhold a big lens for a short period of time, maybe you need a gimbal, maybe you don’t pan as well from a gimbal, maybe a gimbal/tripod allows you to lock the lens on the subject as it stays stationary for hours and get the shot as the action happens. Maybe a short focal length is the right choice, but maybe it makes the background too distracting. Maybe two bodies and two different focal length choices is the way to go. All I am trying to point out here is you need to consider this stuff and be ready for it, because the owl could be there for just one day, just one flight, just one hunt or it could be there for a week. You never ever know, its a wild animal.

If distances are right, I prefer the 600mm – it usually works out to be the right focal length for me for this type of bird and it produces photos that are pleasing to my eye, at times it might have been a bit longer focal length than I needed and on other occasions, I needed more than 600mm.

So, the mention of photographers and long lenses gives me a visual I often see and don’t understand. I make the terrible assumption that a person with expensive equipment (which long lenses usually are) knows what they are doing or should know what they are doing. But anyway, what I see is this, a group of photographers 500mm plus lenses, some with teleconverters attached, all with tripods and gimbals, have their cameras pointed towards the owl (bird) and the sun directly behind the bird. In other words, these photographers are pointing their long lenses into the sun with a subject in-between, no matter how I visualize this, I see a dark bird with no detail, bright, overpowering background blowing out the scene. There may be interesting shots to get pointing into the sun, maybe a silhouette shot is a go, but no sensible photographer would be shooting this way for the whole day, the photos will be sub-par. You need to consider the direction of the light, the sun behind your back, the subject in front of you when possible (specialty shots excluded) – bright overcast might be even better. But no matter what, you must consider the light, direction of the light, how that light affects the subject and its environment. The light can be your partner or it can be your enemy – you make the choice!

You also need to be looking at the background behind your subject, not just the subject. This is important, really important!

- Are visually horrible branches or tree trunks that might overexpose or ruin the scene in the background

- Is the background dark and horrible or soft and beautiful, does it have harsh contrasts, does it make the bird blend with the background or stand out?

- Could you move slightly or change the camera angle to improve the background/subject composition.

- Does changing the angle make the snow stand out more because the background contrasts better with the snow

- Does the background distract from the bird, is the light on the bird and background working together to produce a possible wow shot?

And so it goes on, it’s critical you look at both subject and background, evaluate the whole composition and make adjustments as needed, so many people don’t pay enough attention to the environment.

The other visual horror story I see many times is photographers oblivious to where their uncapped lens is pointing. Leaving it on the tripod pointing straight up in the air, while chit-chatting, oblivious to what might fall or drop onto their unprotected lenses (rain, snow, dust etc.) Why not point it towards the ground where it won’t get crap on it or put the cap/hood on – you can see where I am headed, right?

Ok, shooting in the snow – again, watch where you point your lens, which way is the snow falling, is it swirling around, will it land on your glass, do you have a lens cloth or lens cleaner if it does. Be aware of what is going on in settings like this, you can be out in a full-on snowstorm and manage not getting snow on your glass if you are careful. eg: Change direction so the snow blows away from the front of your lens, not towards it. Snow is very wet and will also freeze if its cold enough, maybe rain gear is appropriate to protect your camera in snow conditions.

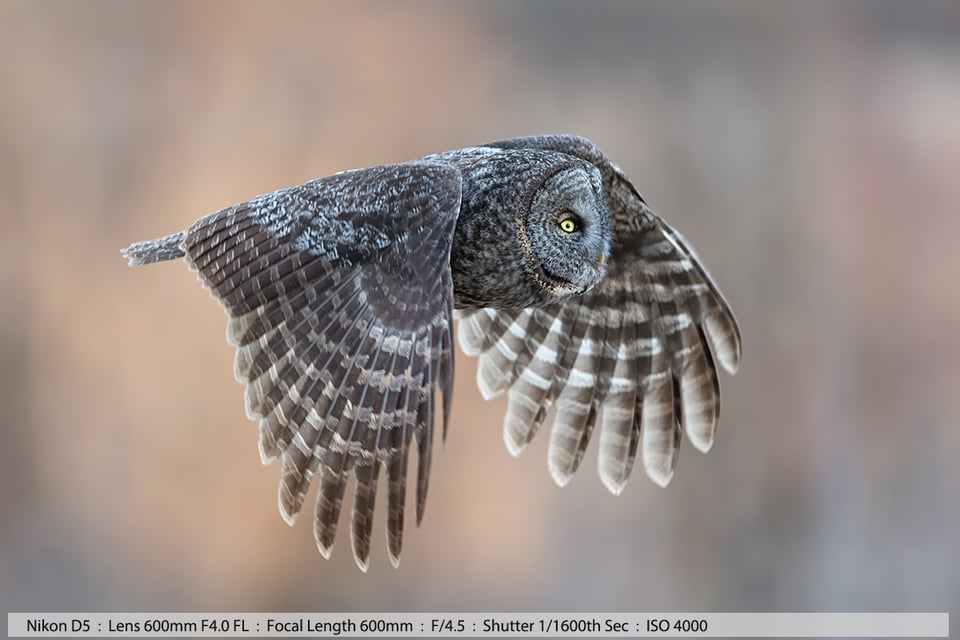

I have mentioned this kind of thing in previous articles – The eyes have it, the eyes are the passageway to the soul, what are the eyes doing on the owl? Are they wide open, can you see those glorious yellow and black eyes, do they stare back into your camera and make contact, when does this happen? Do you even notice what the status of the eyes are? When an owl is about to fly or about to hunt or when it pruning itself or there is a distraction, there is a huge chance the eyes will open wide and if you are aware of that, you will wait for it.

The eyes on this owl are quite impressive and can have a big impact on your photo, in the above photo taken as the sun sets, the owl had just pounced on a vole in the grass (50 people looking on) – it is wound up and hyper (hunting mode) look how wide open and impressive the eyes are in this photo (above). Just an observation: overcast light equals bigger pupils, bright sun equals smaller and sometimes un-even pupils.

Flying shots – how do I get impressive high action flying shot? Ask someone else to give you their photo, just kidding!

First, you have to anticipate the flight or the possibility of flight. Then you have to evaluate the situation, where might it fly, are their obstructions in the way, do you have the speed needed, what is your distance if it flies. After flying there could be landing shots. The great gray owl (GGO) we were following here in New Hampshire, would sit for hours, eyes closed or semi-closed (snooze mode), around 3 to 4 pm it would start to get active, start to hunt, It would drop to the ground, sometimes coming up with a vole, sometimes not, then fly to a lower sitting perch, maybe fly again to another perch or try again to get a vole, but not unusual to have several short flights once it started moving. This is your chance to get glorious flight shots if you are ready for them.

How do you know the owl might fly ? Ask it to give you a heads up, sounds simple right !

Actually birds of prey do display some hints they may fly before they actually do. In this example the common signs of an upcoming launch into flight from our owl was:

- Pre-flight poop – a lot of raptors will poop before they fly

- The bird goes from being fairly relaxed and sleepy to eyes opening more, paying attention to something on the ground

- You can almost see the owl honing in on the possible position of prey on the ground it might attempt to kill and eat

- The owl gets very attentive before flying, it will also lower into a launch position, but launch comes very quick after this

- Also it won’t stay on the ground for that long, be ready after its had a hunt attempt, successful or not – flight is imminent

- After observing it closely for a few times / hours – you start to sense when it will happen.

This GGO stayed in NH for just shy of two weeks allowing for sunny days, overcast day and then a blizzard (March Blizzard) with lots of snow. Snow-covered ground and also ground with no snow, all in 4 days of shooting (I went 4 times). I also travelled to Ottawa Canada before this owl showed in NH.

A consideration when shooting in a snowstorm – lots of snow equals lots of obstacles between your lens and the subject’s eyes – what I try to do here is shoot fast (11fps) bursts and many of them in the hope that one frame will have both eyes clear of any snowflake obstruction or blur from snowflakes. I might, for example, take 10 or 15 short bursts of 10 plus frames when I review, I am looking for the one or two frames where the eyes are clear and sharp, too much snow can act like a fog or haze rather than snow, too little can just be a nuisance rather than look like snow. The further you are away from the subject, the more chance snow flakes will be an issue as there is more snow between you and the subject. Maybe sneaking a little closer will result in a clearer shot. But more shots are better in this situation, many shots will be trash can material because of environmental issues caused by the snow.

I have used my GGO experience here to cover some of the important things to consider for what might be a very short photographic opportunity, I may not get to see another GGO in New Hampshire in a long long time.

So how did I maximize my opportunity here.

- I went as often as I possibly could, it was a 2 hour drive and I work a day job, but we did what we could to get there (my friend took days off work)

- I stayed as long as I could, but I also learned it was more active in the afternoons so that was more productive time.

- I brought lots of empty memory cards – took more frames than I normally would, can always delete if crap.

- I changed my angles and backgrounds to give different looks to the photos

- I looked for snow opportunities – both falling and owl on ground with snow

- I waited for hunting and flight opportunities and was extremely attentive to the owls disposition to get these shots

- I waited until sunset / dusk to try and get shots at last light

- I experimented with distances and angles to create artistic shots

- I went home and evaluated my days work, to see what I had gotten, what I needed to get, what I needed to improve on, mistakes

- I tried to understand the owls behavior and patterns, like when it hunted, it often flew along the tree line from perch to perch in a semi predictable manner

- I made sure my camera settings and speeds would work for the scenarios presented to me – ISO / Shutter Speed / Focal Length etc

- I recognized this may be a once in a lifetime event here in NH and that made it important to get things right – the first time.

This final photo below is one of my favorites from my 2017 GGO experience:

That photo highlights some of my key points of why I made the choices I did, the 600mm focal length is creating beautiful bokeh that totally separates the bird from the background, the 600mm focal length helps make the owl fill more of the frame than the background, the 600mm focal length kept me far enough away to allow flight but close enough to get the shot. By being aware of the background, I saw the opportunity to place this pastel-like background behind the bird rather than the dark gray forest. I did get lucky: the wings almost got clipped (cropped) but I consider my 600mm choice a high risk / high reward one. But this kind of photo is what I strive for, the separation / the clarity / the light / the action – I wish they could all be like that – lol

I hope you recognize and maximize the rare opportunities that might come your way. Now, go out there, have fun, enjoy the experience and good luck

PS: In the short time this GGO was accessible in NH, the owl created quite a following from both birders and photographers. Try googling “Newport NH Great Gray” and you will see some photos including this owl deciding to land on someone’s lens as they are taking photos of the owl in flight and once it even landed on a persons head (wearing a hoodie) of its own free will. I have never seen such behavior before from a wild bird, but I am told that this can be common for the owl (great Grays). In any case, I did see it land on a persons lens then move to a freestanding tripod and use it as a perch – a lifetime experience for me – wow!