What are the best walk-around settings for wildlife photography? Perhaps you just bought your first camera and want to photograph some wildlife. Or, maybe you’ve been struggling with capturing crisp and properly exposed images of wildlife for a while, and you need some guidance. If that sounds like you, read on!

Photographing wildlife can be a real challenge. Animals have sporadic movements, an affinity for low-light conditions, and (literally) minds of their own. Almost anyone with a camera has dabbled in wildlife photography at some point. But good results can be scarce at first, and many photographers don’t go any further in the genre.

That’s why I wrote this article. Today, I will introduce you to the proper walk-around settings for beginning wildlife photographers to ensure you capture images you can be proud of. I’ve covered shooting modes, autofocus modes, and how to optimize your settings to take better wildlife pictures.

Table of Contents

Challenges of Wildlife Photography

What makes wildlife photography difficult? For starters, most animals you’ll encounter are moving subjects. Birds are almost always on the move, bugs will sway on a leaf in the wind, or a coyote could be on its morning prowl. This is why it’s so important to shoot with a fast shutter speed so that your images are not blurry due to motion blur.

The second challenge is that, by definition, wildlife is wild. The animal you’re photographing may not decide to stand in the perfect spot for a photo. Or, it could suddenly face away from you or change direction entirely. You need to be aware of these possibilities when setting up your composition and autofocus settings, or you risk poor framing and out-of-focus images.

Thirdly, it’s often dark when wildlife is the most active. For many animals, the best time to photograph them is early in the morning or during the last hours of twilight. Even if you find a good subject during the middle of the day, the animal may be in a forest or burrow where the ambient light level is low. In low light, you’ll be straining your camera settings in order to properly expose the image.

There are other challenges when photographing wildlife, too, but those are the three that I find the most important to keep in mind.

Recommended Camera Settings

In photography, three camera settings determine how bright your image will be: shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. (Flash intensity is another, but flash photography is a more advanced topic in wildlife photography that needs an article of its own – and many wildlife subjects are too far away for flash to be helpful in the first place.)

The optimal settings depend on the ambient light level when you’re taking pictures. Generally speaking, low light requires a longer shutter speed, wider aperture, and higher ISO. Bright ambient light allows you to use a faster shutter speed, narrower aperture, and lower ISO.

Let’s dive into exactly how each of these factors affects your exposure and other aspects of the image.

1. Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is the amount of time your camera allows light to hit the sensor and expose the image. We’ve covered it in detail before if you want to refresh your memory.

Most cameras can be set to have fast shutter speeds like 1/4000 of a second, as well as long shutter speeds like 30 seconds. The faster your shutter speed, the less light that hits your camera sensor, which puts you at risk of underexposure. But it also allows you to freeze movement.

This doesn’t just include the movement of your subject, but also camera shake caused by handholding the camera. With fast-moving subjects and telephoto lenses (which magnify shake), wildlife photography is the perfect storm that requires a fast shutter speed.

Personally, I try to stick to 1/250th of a second for wildlife photography, and faster (sometimes even 1/1000 second or 1/2000 second) if my subject is moving very quickly. With too long of a shutter speed, like 1/60 second, you’ll start to need a tripod in order to eliminate camera shake, and a moving subject would not turn out sharp.

2. Aperture

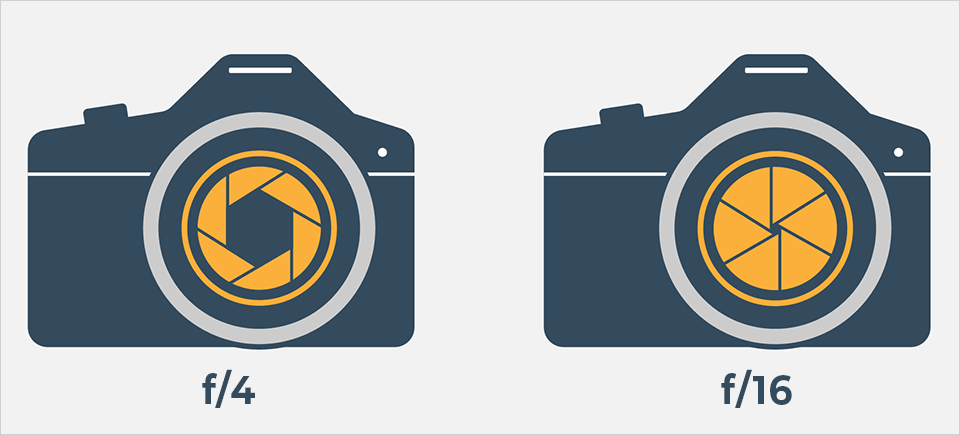

Aperture is the size of the opening in your lens and how much light it can gather. It looks like this:

You can read our full article on aperture if you aren’t familiar with it, but the basic idea is this. The larger the aperture, the more light you capture. That’s why a large aperture is such a useful feature in wildlife photography.

As you may have heard before, your aperture value is written in f-stops. If you set your camera to an f-stop of around f/2 or f/2.8, it means that the aperture blades in your lens are open fairly wide, capturing a lot of light. As you jump the f-stop to higher numbers like f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, and so on, it means that you are closing the aperture blades more and more, which results in much less light being captured.

Aperture is very important in wildlife photography not just because of how much light it captures, but also because of depth of field. At wide apertures like f/2.8, your photos will have a “shallow focus” effect where only your subject is sharp, and the foreground and background are out of focus. At narrower apertures like f/11 and f/16, depth of field increases. This changes the look and feel of a photo, so it’s important to get your aperture right.

3. ISO

ISO is the third camera setting that changes how bright and dark your photo is. However, unlike shutter speed and aperture, changing the ISO doesn’t actually capture more or less light. Instead, it’s a lot more similar to changing a photo’s brightness in post-processing software like Photoshop. (More on how that works in our detailed ISO article here.)

So, even though higher ISO values will brighten your photo, it’s not a magic solution to shooting in low light. You’ll notice that if you set too high of an ISO – as opposed to capturing enough light in the first place – your photos will turn out very grainy and noisy, with strange colors and a lot less detail.

What ISO values should you use for wildlife photography? My recommendation is to stick to ISO values between about ISO 100 (best image quality) and 800 (acceptable image quality) with most entry-level cameras. Even cameras that are 10+ years old can still produce usable images up to about ISO 800. Some of the newest full-frame cameras still look good up to ISO 3200 or 6400.

But whenever you have the choice, it’s best to avoid having the boost the ISO too high. Take a look at your shutter speed and aperture and see if you can capture more light in the first place. Maybe you’ll notice that you’ve programmed a shutter speed of 1/2000 second when you could easily get away with 1/500 second (capturing four times as many light) and a substantially lower ISO.

I recommend doing some test photos at different ISO values to see what looks acceptable on your camera. Sometimes, we are forced to push the ISO higher than is ideal and settle for a slightly grainy image. But that’s still better than getting a blurry subject because your shutter speed is too long.

If your camera doesn’t have a designated ISO button, I recommend making one of your customizable buttons your ISO control. You want fast access to changing your ISO because you will find yourself changing it frequently.

Combining the Three

Now for how these factors relate to each other. A properly exposed image is produced when shutter speed, aperture, and ISO are balanced with the ambient light. In darker environments, shutter speed must be longer, aperture must be wider, and ISO must be higher. In brighter situations, you have a lot more flexibility to use a faster shutter speed, narrower aperture, and lower ISO.

In any light level, there’s not just one combination that results in a well-lit image. In fact, there is a wide range of combinations that can properly expose the image. The challenge is to find a combination that eliminates unwanted motion blur, provides the right depth of field, and doesn’t capture excess noise.

In wildlife photography, the priority is usually to have a fast shutter speed. This is because the subjects are frequently moving, plus we are often zoomed in, which magnifies any camera shake in the first place. The most common cause of a blurry wildlife photo is too long of a shutter speed.

Camera Shooting Modes

With most entry-level cameras, you will have the option to shoot in automatic mode, shutter speed priority, aperture priority, or manual mode.

In automatic mode, the camera automatically sets shutter speed, aperture, and ISO to properly expose the image. However, it gives you no control and isn’t geared toward photographing wildlife, so I never recommend using it.

In shutter speed priority mode, you manually set the shutter speed and the camera automatically chooses the correct aperture to properly expose the photo (ISO can be manually set or on auto). Aperture priority works the same way except you set the aperture and the camera chooses the shutter speed. In manual mode, you set all of the settings yourself.

1. Aperture Priority

The best shooting mode for wildlife photography is aperture priority.

You may wonder, “If I want to prioritize a fast shutter speed, why not shoot shutter speed priority?” The answer is that aperture priority speeds up the process. In low light conditions, you simply set the widest aperture on your lens – something like f/2.8, f/4, or f/5.6 on most wildlife photography lenses – and pay careful attention to where your camera is floating the shutter speed. If the shutter speed gets into dangerously slow territory, just bump up the ISO, and you’ll be good.

For my wildlife photography, I usually set my aperture at f/5.6 (the widest on my lens) and keep it there the whole time. I set my ISO to about 800 in typical lighting conditions, and as the evening progresses and it gets darker, I usually have to increase my ISO to maintain a fast shutter speed.

You can automate this “steadily increase ISO through the evening” process using your camera’s Auto ISO dialogue. Don’t be fooled by “auto” in the name, because it’s an advanced technique that requires you to have full understanding of how shutter speed, aperture, and ISO work. We have covered the Auto ISO process before and why it can be so powerful for wildlife photography.

2. Shutter Speed Priority

Even though shutter speed is so important to wildlife photography, I don’t usually recommend shooting shutter priority. In bright lighting conditions, shutter priority will change your aperture value too much (which can give you the completely wrong depth of field). In dim lighting conditions, you run the risk of the camera pushing the ISO too high if you don’t constantly change your shutter speed.

It’s not the worst mode in the world for wildlife photography and I know that some photographers prefer it, but I like the extra control of aperture priority, not to mention its versatility in different lighting conditions. If you do choose shutter priority, just be careful to watch the aperture and ISO values at all times.

3. Manual

Many wildlife photographers like to shoot in manual mode with Auto ISO. This involves setting your shutter speed to a manageable speed and, in most cases, using the widest aperture on your lens to capture as much light as possible. The camera will then float ISO depending on how the light changes.

This is a perfectly good way to shoot in low-light conditions. However, in bright light, you run the risk of hitting the camera’s ISO floor (like ISO 100) where it can’t go any lower. After that point, if the light gets any brighter, your photos will be overexposed, because the camera has no remaining way to darken them.

Also, I strongly recommend that you do not manually set the ISO as well when you’re in manual mode. If you do, and all three settings are manual, you’ll need to do too much trial-and-error and fiddling with your camera settings constantly. This can cost you precious time when you’re photographing an animal that may not be in the perfect spot for long.

4. Automatic

Do not use auto mode! If up until now you have been shooting on automatic, this is your sign: it’s time to step up your photography game. Automatic is a wild card because it may not optimize your shutter speed to capture a sharp wildlife subject. It may prioritize a low ISO instead of a fast shutter speed, or it may narrow down your aperture when you desperately need to capture more light. You never know when it will do something funky that results in a suboptimal shutter speed, bad depth of field, or high grain. And worst of all, it takes away your control of how the photo looks.

Exposure Compensation

Although the camera’s aperture priority mode tries to properly expose the scene, wildlife photographers often find ourselves shooting in scenarios with harsh light, as we can’t control the scene. Examples of this are shooting against the sun or upwards into a tree on a backlit subject. Other times, you may be shooting a very bright subject like a white bird against a much darker background. Even though modern cameras are pretty good at metering, these situations can still cause the camera to fail to properly expose your subject.

To quickly correct any errors, you should take advantage of exposure compensation. This is usually represented by a +/- symbol on the camera. An exposure compensation of +1 will make the image 1 stop brighter (AKA twice as much) compared to how the camera would otherwise expose the image. Likewise, an exposure compensation of -1 makes the image 1 stop darker (half as bright).

Often, the camera isn’t going to be that far off, and your exposure compensation adjustments will be fairly minor. I usually only adjust it by +0.3 or -0.3.

But in some scenarios, you’ll have to more drastically adjust the exposure compensation. For example, let’s say I’m shooting a crow up in a tree on an overcast day. The dark crow is in front of some bright clouds. When I review my first shot, I notice the crow is just a black silhouette against some properly exposed clouds. This is because the camera was a little confused and exposed for the clouds instead of the crow. Since I want to be able to see the details of the crow, I bump my exposure compensation up a couple stops to +2. Now when I take the shot, my subject is properly exposed and the background is slightly overexposed.

That’s why it’s useful to have a wide range of exposure compensation values at your disposal. Wildlife photography can fool a lot of cameras, so if you want to prioritize the exposure of your subject, exposure compensation is a very valuable tool.

(I will mention as a final note that exposure compensation is not a variable of exposure on its own. All it does is shift shutter speed, aperture, or ISO in order to change the exposure.)

Autofocus Modes

Along with motion blur, the other most common cause of blurry wildlife photos is missed focus. The best way to understand your camera’s focus system is to practice, but I also recommend relying less on the automatic focus modes and giving yourself more manual control.

1. Single Point vs Wide Area Autofocus

Exactly how to set your autofocus depends on your camera model. They all have different options, so I’ll make my recommendations more general in nature.

First, I recommend using a small autofocus box rather than a large one. Many cameras have an Auto Area Autofocus mode, where the camera decides on what it “thinks” your subject is in the photo and tries to focus on it. I hope I don’t have to explain why that’s a problem!

Another common mode is Wide Area Autofocus – a large box that you can position in your frame, at which point the camera will focus on something in the box (usually the nearest object). The problem with wide area autofocus is that it doesn’t always pick your subject out of the box. Often, we are shooting through vegetation, which will attract the attention of the focus system. The camera will end up focusing on some blade of grass or leaf instead of your subject’s face.

The option I prefer is a small autofocus box that you can position across the frame. Whatever it’s called on your camera, the key is that the camera will focus on whatever is in the little box. While you do give up some speed since you need to move the box to the perfect spot, you’ll end up getting sharper photos in the end, where the camera focuses on the subject instead of its surroundings.

In some autofocus modes, the camera can lock onto your initial subject and then track it around the frame. In others, you must manually move around the focus point as your subject moves. You’ll want to test out both approaches to see which one gives you quicker and more consistent results. I personally favor moving the box around manually much more than some wildlife photographers, so I often stay away from the tracking modes. But if you shoot very fast-moving subjects like birds in flight, you may find that autofocus tracking is a lifesaver.

Either way, you should make sure you can quickly change your autofocus point when you need to. It may be possible to assign one of your camera’s custom buttons to turn autofocus tracking on and off. Refer to your camera manual and spend some time practicing to figure out which technique you prefer.

Single vs Continuous Servo Autofocus

Your camera likely has the option of AF-S (single-servo autofocus) or AF-C (continuous-servo autofocus). When shooting with continuous autofocus, your camera will keep refocusing constantly so long as you hold down your focusing button. Whereas in single-servo autofocus, the camera will only engage autofocus once each time you press the focusing button.

Continuous servo can be useful for rapidly moving subjects such as flying birds. But, like autofocus tracking, I find that it is often overused by wildlife photographers. In my experience, AF-C often ends up racking focus too far and misfocusing when your subject is staying pretty still, getting stuck in an out-of-focus state. AF-S provides more certainty that your camera will focus exactly where you want.

Even though wildlife is constantly on the move, most animals also spend a lot of time waiting or resting in one particular spot. Continuous autofocus is a good idea when your subject is truly going wild, but don’t discount single-servo AF for day-to-day wildlife photography. You may find that it gives you better results overall.

Conclusion

I hope you now have a better understanding of how shutter speed, aperture and ISO affect your exposure, and how to best optimize these settings for wildlife photography. I also hope that my autofocus tips gave you something to think about.

To sum everything up, I recommend shooting in aperture priority mode. In low light, set your aperture as wide as possible, and bump up your ISO until your shutter speeds are fast enough for your subject (meaning at least 1/250 for a lot of wildlife). In brighter situations, you have the luxury of lowering the ISO and getting better image quality. Lastly, if your images are still turning out slightly too dark or bright, you can use exposure compensation to correct for that error.

As for autofocus, use a small focusing box so that you have control over where your camera focuses. And keep in mind that you don’t always need to use continuous-servo autofocus with full subject tracking around the frame; single-servo can often do a better job if your subject isn’t moving too fast.

With these settings, you will be able to photograph active wildlife in suboptimal lighting conditions and still get results you can be proud of.

What an invaluable and clearly set down piece of information, to anyone new to a more serious interest in photography.

Thank you.

I have tried doubling the focal length for shutter speed (1/500), largest aperture (5.6) and auto ISO for shooting birds and squirrels in the back yard. (Roughly 10-30 ft) Color saturation and clarity is good. 5 big trees in the back for broken shade. Auto focus on. No filters. It works in this situation

Why do you have females running around naked on your website?

Why do you have three clipart images of men on your webpage, but no women?

Whenever you feel compelled to ask such questions then, for your own safety, try to remember that it’s nature’s way of telling you to:

1. stay indoors

2. keep away from everything that’s connected to/with:

• cell towers

• telephone lines

• radio or TV antennas

• satellite dishes

• the Internet

• people

• pets

• pot plants (especially)

Deet mosquito spray erased all of the lettering on my cameras buttons. I hope photography life has some suggestions. I think I will try a paint pen. It will be very expensive to repair. You should write an article about deet. Does damage the weather sealing and the plastic housing?

Very useful article! Thanks for sharing and providing a quick crash course 👍

Very useful article! I like Wildlife photography though I am mostly a seascape photographer. I am totally agree about one shot AF vs AI Servo (I am Canon user, forgive my different terms). For years I used AI Servo along with back button focus for being able to have the best of both worlds BUT, that is very bad for stills! The camera never locks the focus perfectly (though it gives a focus lock signal) even if you release the focus button and that gave me a lot of misfocused images. Initially I blamed it to my Tamron 70-210 f/4 for bad calibration but that wasn’t the case, since I had the same issue with the Canon 70-200 f/2.8 and in any case, there was also photos that was razor sharp (let’s say I had 6 out of 10 perfectly focused images). After a lot of trial and error I tried to use One shot AF and suddenly I had perfectly (9 out of 10) sharp photos, both on OVF and DualPixel AF and even in low light!

I have only one objection for using Aperture Priority in cases where shutter speed is critical, especially on cameras that doesn’t allow a setting of minimum shutter speed. It will be too difficult to control the shutter speed and you will often end up with unnecessary ISO. For me a general rule of thumb here is to use Manual only. Just set an aperture and a comfortable ISO (depending on your camera) that allows you speeds over 1/500th for 0 EV. Then you can adjust only your shutter speed for EV or fast moving subjects.

I am not a beginner (well, maybe at wildlife photography), but this article was a great refresher. I found your recommendation of using a single focus point instead of continuous focus tracking to be interesting and counterintuitive. Finally, great shot of the Tule Elk at Pt. Reyes at sunset!

Many people who benefit from this article are going to be out there with their first new-to-them long lens (say, 500mm), and they’re going to wonder why they keep missing focus, even on shots where the subject was still. Nobody seems to care much about focus fine tuning until you whip out a 500mm lens and try shooting it wide open, but it is quite common for long lenses to need to be fine tuned to match the DSLR body. If you are shooting gnatcatchers at 15 feet and your focus is off by half an inch, most of your shots will be garbage. If that’s happening to you, and you haven’t focus fine tuned that long wildlife lens to your DSLR body, spend the $5.50 for a cheap Lens Focus Calibration Tool (it’s a foldable piece of cardboard with patterns printed on it), and Google “how to focus fine tune [your camera model].” It is the second best bargain in wildlife photography (after the low, low cost of reading photographylife.com).

Great article! I only would add Back-Button Autofocus as a superior alternative to half pressing the shutter button to the list. That way you have the benefits of single and continuous AF without the respective shortcomings. Nasim described this once in an article in these pages, I tried it and never went back.