For the past year or so, my main camera for landscape photography hasn’t been one of the newest high-resolution mirrorless cameras that I spend so much time writing about. Nor has it been an ol’ reliable DSLR. Instead, I’ve been using large format film, especially a 4×5 camera.

When other photographers see the camera, they usually say something like “Wow, old-school!” But that’s only partly correct.

On one hand, 4×5 cameras are the definition of old-school photographic technology. They’ve existed in some form since about the 1830s. Yet they’re still made today with the most current manufacturing techniques. My 4×5 camera was built in 2021, making it the newest camera I have. In its own ways – including the modern materials like carbon fiber – it’s surprisingly cutting-edge.

I’m working on a longer guide that’s a full introduction to shooting 4×5 film: whether it’s right for you, what gear you’ll need, how to process your images, and so on. Today, though, I just want to explain why 4×5 film (and larger) continues to be relevant even in the 2020s.

The truth is that there’s no perfect tool in photography, and everyone’s needs are different. But there are still a few reasons why film makes sense these days and why I’ve been using it for most of my recent landscape photography work.

Detail and Sharpness

I’m a sucker for maximizing image quality. It’s why I go through the hassle of focusing at the double-the-distance point, setting the optimal aperture, using good lenses, and doing everything else in my power to take landscape photos that are as detailed as possible. Certainly, detail isn’t the most important part of a photo, but there’s some satisfaction – maybe just satisfying my misguided perfectionism – to capturing the highest possible image quality anyway.

The stereotype of film is that it takes the exact opposite approach. It is unavoidably imperfect. Film offers color shifts, light leaks, endless grain, and countless other artifacts in your images. It’s meant for, I don’t know, Wes Anderson? Hipsters? That sort of crowd.

But while film can be like that, it doesn’t have to be. It’s very flexible. You can shoot expired film on a broken Pentax K1000 and get all manner of “interesting” effects. Or you can shoot a modern film like Kodak E100 (most recently re-formulated in 2018) on a large format camera and get detail in spades.

4×5 film – which I used to take most of the photos in this article – is the smallest “large format” size. The biggest popular size is 8×10, which is four times the area of 4×5 (similar to the difference between Micro Four-Thirds and full-frame cameras). Other film sizes are even larger, albeit exponentially harder to work with, and rarely available in color.

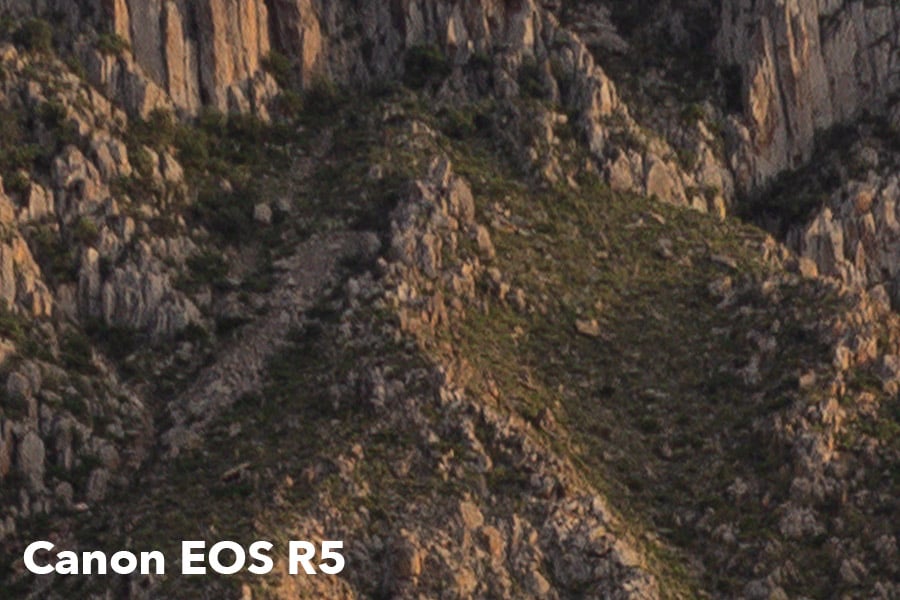

So, when I show you the following comparison of sharpness and detail – the 45-megapixel Canon EOS R5 versus 4×5 film – keep in mind that it’s possible to achieve more detail than this with large format film if you’re so inclined (or with digital, by using higher resolution cameras).

Here’s the image from the EOS R5:

And the image from a 4×5 setup:

The compositions aren’t perfectly equivalent because the two cameras have different aspect ratios. The Canon EOS R5 has the typical 2×3 aspect ratio of a full-frame mirrorless camera, while the 4×5 setup has, of course, a 4×5 aspect ratio, which is more squarish. Still, I framed them as best I could so that the two photos would be comparable.

In fact, taking a closer look at the images above, it’s difficult even to tell that one is film and one is not. I do like the colors a bit better on the 4×5 shot, but the two images are close enough that I could probably make them look about the same in Lightroom. In other words, film can look very digital-esque if that’s what you’re after.

Detail slightly favors the 4×5, as shown in the 100% crops below (click to slide between the two images), but they’re pretty similar:

If I had paid big bucks to have the film drum scanned, the 4×5’s quality would a bit higher than it is, but I’m perfectly happy with the file from my desktop Epson scanner. That said, the film photo does have slightly more grain in uniform areas like the sky (though not much, as Kodak E100 is a pretty low-grain film). In any case, if you’re after the totally clean look, digital has the edge.

So, hopefully it’s clear that large format film doesn’t lack image quality. However, some digital cameras can beat the level of detail from a 4×5, such as a 100-megapixel medium format camera or the sensor-shift mode on cameras like the Panasonic S1R and Sony A7R IV. The good thing with film is that there’s always a format with increasingly more detail if you need it. Jumping up to 5×7 or 8×10 – especially combined with drum scanning – will increase your resolution many times compared to what I’ve shown here.

Dynamic Range and Colors

Digital sensors today have simply outstanding dynamic range and almost limitless shadow recovery. What about film? You may have heard conflicting things – either that it has a narrow dynamic range, or that it has far better highlight recovery than digital. Which is true?

The answer is that it depends on the film. Color negative film like Kodak Portra 160 has fantastic highlight range, practically unlimited. I’m working on direct, side-by-side tests, but my initial impression is that color negative film roughly matches digital sensors in total dynamic range (though it’s biased toward good highlight recovery with film and good shadow recovery with digital).

Meanwhile, color positive film – AKA slide film – like Fuji Velvia 50 and Kodak E100 have a more limited dynamic range with less shadow or highlight recovery. They need to be exposed more carefully. Still, I’ve found very few real-world situations where I run out of dynamic range on slide film, especially on Kodak E100 and Fuji Provia 100.

As for colors, it’s an interesting situation. To me, the color rendition of a good film is better than a digital sensor, especially in red tones, but some of that advantage is thrown away when scanning the film (as opposed to printing optically from a negative or looking at a slide on a light table/projector).

There’s also a difference between color negative film and slide film, especially if you’re scanning them yourself. Color negative film can take a long time to edit digitally to get optimal colors. On the other hand, slide film requires minimal edits and almost always boasts great colors. Digital raw files are somewhere in between. I still find it’s possible to get a similar appearance among the three after pushing them around for a while, but the differences out-of-the-box clearly favor slide film.

I’ve also noticed that film tends to capture finer color details than digital, which are visible if you magnify the images substantially. In the extreme crop of the photo below, for example, I don’t believe I could have captured the variety of nearby, distinct colors on digital as well as Portra 160 negative film did:

Overall, the three choices – color negative, slide film, and digital – are simply different beasts. Digital is extremely versatile if you shoot raw, especially in terms of dynamic range and shadow detail. Meanwhile, the best colors I’ve captured have been on film, especially slide film, and the best highlight rendition is the domain of color negatives. That’s why I always carry both slide film and color negative film (plus some black and white negatives) when I shoot large format film! And why there’s still usually a digital camera in my bag, too.

Movements

On a typical large format camera, every lens becomes a tilt-shift lens. Moreover, if you buy lenses with large enough image circles, you’ll have almost unlimited levels of tilt and shift at your disposal, along with rise, fall, and swing.

This lets you adjust two major factors of an image – depth of field and composition – in ways that are often impossible with digital. Tilt (as well as swing) lets you align the plane of focus with your subject, while shift (as well as rise and fall) lets you adjust the composition without realigning the camera itself.

When I started shooting large format film, I expected to use tilt far more than any other movements. But it’s actually been rise and fall that I use the most. The reason is that a classic challenge with forest photography – a subject I’ve been shooting a lot recently – is to avoid skewed trees. Pointing the camera even a bit upward will angle your trees as if they’re all falling away from you. It’s not always a bad effect, but it can get old quickly.

On the other hand, with my large format camera, I just point straight at the trees and use rise instead. The trees don’t go askew, and the photos look more natural to me.

Certainly, the same thing is possible with digital images if you do keystone corrections in Lightroom or Photoshop. But those corrections come at the expense of stretching the image, not to mention losing resolution when you inevitably need to crop the corrected shot.

Even though I’ve been using rise and fall more than the other movements, tilt corrections – and occasionally swing – are also a big help for aligning the plane of focus to the subject. They work great on “classic” landscapes where there aren’t any foreground elements breaking the horizon. This way, you can maximize sharpness across the image.

Of course, digital photographers have ways to extend depth of field, too. The main technique is focus stacking, which does a great job extending depth of field when nothing in the scene is moving very much. Still, I find the film process more flexible, especially if you want to combine tilt and shift effects. You can easily compose a large format film image with the optimal rise, shift, and tilt all at once. By comparison, on digital, you’d need to capture a focus stacked image and then perform keystone corrections on the resulting composite – potentially leading to some unwanted artifacts from either process.

Enjoyment

The final and possibly most important reason why it can be worth shooting large format film is simple enjoyment.

I love digital photography. And I love film photography too. They’re different processes and both rewarding in their own ways. I find that I take slightly different photos with large format film, since it slows me down (which is both good and bad) to really linger on my subject.

Shooting 4×5 film – and larger – has also sparked some extra interest in photography for me. I’m going out more often and spending more time putting conscious thought into my photos again. I’m also re-evaluating some of my skills like my tripod technique and metering process that had lapsed some over the years.

Then there’s the entire darkroom process, which I’ve finally started doing for the first time since college. It’s a lovely way to spend time and a hobby in and of itself – which is really what all this is about for me. Yes, I write for Photography Life as a job, but I still consider photography my hobby and want it to be something I keep enjoying. Every photographer is different, but for me, film has helped with that.

This is far from a “film beats digital” article, and frankly if I had to choose either I’d say that “digital beats film,” especially for most professional use today. Yet I’m shooting film more and more. Part of that is because the results – if everything goes well – beat what I’m personally capable of achieving with digital.

But the other part is enjoyment. At the end of the day, that’s really why large format film (and film in general) remains relevant and is even seeing a resurgence. Simply put, it’s a lot of fun. In a very digital world where many of us, including me, are addicted to our screens, the tangibility of film is a welcome relief.

What you don’t mention is, that you lose quite a lot of quality digitizing film.

Best way to compare digital and analog, is making prints.

Visualize the grain in film and the pixels in digital, each with their own qualities and you will see that digital can never reproduce the structure of film in pixels.

Most of the time, that’s not a problem, but in fact it’s unfair to film, compairing like this.

There is a photo that was taken in the early to mid 1930’s that has very small wording in one particular area which is not at all clear. I am wondering if I can take a photo of this 1930’s photo that would produce a photo that could possibly make the wording easier to read. The 1930’s photo is of historical interest.

Very objective analysis indeed. Perhaps within one of your images, the first rocky outcrop image, in my view the 4X5 version is hands down the choice. Does it come down to word analysis? Acuity? Or acutance? That image is a good general case of that. I also agree with the color accuracy, or prowess in film. To be brief. It all makes one wonder where we would be in this issue if in rewind, technology stuck with film and improvised on it. Labels like, “Organic,” when referring to film is tired. I feel, and the operative word is, feel, that film given a chance finds our hearts.

Really great article. Thank you so much for your objective analysis. I am about to embark late in life into 4×5 complete with darkroom processing. Personally I am not enamoured with digital. My early teenager and beyond years of B&W processing are deeply rooted in my psyche and we are so fortunate we are still able to shoot film.

I‘m in the same situation, working mainly with 50mp DSLR‘s every day I enjoy my new found love for LF film so much… starting my work as a photographer in the film age and using only MF cameras, I love your image comparison at the beginning with the color mountain image. Just looking at both images my heart opens up when seeing the 4×5, it is just something pleasing to my eyes and to my visual memory, the 3 dimensionality and aspect ration just adds to that and so when there is something important for my personal work I take the LF camera out… Thank you for the inspiration.

I have worked for 40 yrs with 13x18cm Linhof, Sinar/Schneider cameras/lenses and I still have those files (scanned with 800.000$ Hell drum laser scanners in the 2000’s ). No comparison with my digital Hasselblad files of today. World moves forward (in photography at least!). Not to speak about the film holders loading and unloading hassle.

Thanks for the article, Spencer. Inspiring. I have a Zone VI 4×5, purchased new in the early 1990s. Two lenses, the Nikon 90mm f/8 and the Rodenstock Sironar N 210mm f/5.6. I may compare the large format images, especially the Nikon 90/8, to the digital images from either the Z9 or D850 with my Zeiss 25/1.5 Milvus. It should be interesting. Any bets? The sharpest print I have in my house was taken with the Rodenstock on Velvia 50, developed by a local lab, then scanned on my Epson 700 perfection flat bed. At 20×24, the corner to corner detail is amazing.

I’m in the process of setting up my darkroom. I plan to do mostly B&W, as I can develop it quite easily using the Stearman Press sp-445. I’ll even be able to print B&W if I so desire. I’m looking forward to shooting more 4×5 film, the process is more contemplative than digital.

Almost 55yo and 40 shooting photos. I Bought my 4×5 back in 2000 after falling in love with it back in ’95 when a photographer came to my office to shoot some commercial images.

I am deeply in love with this camera mostly because you need to take your time before shooting. Time to frame, to think, to wait for the right light. It feels like painting, you sit in front of your subject and wait for the magic to happen.

So after my camera has been sitting in the bag for “long time” last year I decided to take it with me. Again the feeling of using this kind of camera as no comparison with Digital. I had 150 sheet stored in my freezer for 15y and yet, after developed, are just perfect. Both color and BW are perfectly working.

However there is a big cons. In Italy it is very difficult to find film and it is very expensive to develop it. As I don’t have the space and time to develop color (not E6 only C41) and BW myself I took my sheets to a very well known local shop in Bologna. I paid €90 to develop 9 photos!!!

So I decided that until I buy all the tools I need to develop my film the camera will have to go back to the basement. :(

Thank you for helping keep film alive.

Explaining analog at times is trying at best but I get a lot of photographers converted once they see the final image.

Again, thank you for sharing your knowledge

I’m 55yrs behind the ground glass and love it as much now as I did then

Davidbinnick.photography

I appreciate you working up a comparison of image detail with the R5 and 4×5 film. Really wish you would have used the highest quality lens available for the R5, and spent the extra $ for high quality Tango drum scans. That’s the only way we would know for sure how the R5 stacks up to 4×5 film.

I have my 4×5 transparencies scanned on a Tango, and the final image size is 1.2 GB. The results are spectacular.

I’ve been shooting the landscape with 4×5 since 1982, and the camera movements afforded are what keep me shooting large format. The control over depth of field (mostly extending it), and perspectives is so easy to accomplish, and such a joy.

Neither system can do it all. 4×5 is limited in longer focal length lenses, and digital can’t provide practical offerings for perspective controls, and depth of field. That’s why I carry both systems.

‘Thank you’ for putting this article together.

Sure thing Bruce! I do intend to do a proper comparison in a later article — this was mainly a proof of concept that film can reach the level of full-frame, high-res digital.

I carry both systems too, although more for weight purposes than anything else. I try to pack along the biggest feasible camera for any given trip, whether that’s digital, 4×5, 8×10, etc.

I do not agree Spencer. A H4D Hasselblad file is way better than a Ekta E6 13x18cm scanned in a Hell DC350 drum scanner and shot with a Schneider 90mm XL on a Linhof. New digital lenses deliver better performances (because the sensor requires better performances than chemical). You shold specify if you are talking poetry or performances/usability. I have had 8 Linhofs, Sinars and other BF cameras with lots of Schneiders, Rodenstocks and Nikkors BF lenses…. sorry but, poetry apart, photographic technology is way better now.

Do you mean way better as in image sharpness? or overall image quality. I had a Hasselblad digital and I still prefer my large format film shots. I think it’s just subjective. plus you have movements with view cameras. Fun to use over a digital camera in my opinion.