For a number of years I have been recommending our readers to convert RAW files from their cameras to Adobe’s DNG format. In my DNG vs RAW article from 2010, I pointed out the reasons why using DNG over RAW made sense – it simplified file management, resulted in smaller files (when compressed or when embedded JPEG image size was reduced) and seemed like a good way to future-proof RAW files. But as time passed, higher resolution cameras were introduced and I started exploring other post-processing options, I realized that DNG had a few major disadvantages that made me abandon it. In this article, I will revisit the DNG format and bring up some of my concerns on why it might not be the ideal choice that I once thought it was.

Let’s take a look at some case scenarios and see what advantages and disadvantages the DNG format has when compared to RAW files.

Table of Contents

1) DNG Conversion Increases Workflow Time

Whether I choose to convert my RAW files to DNG upon import or at a later point of time, the conversion process puts a significant burden on my import time and only complaints my workflow. While converting small RAW files from low resolution cameras is barely noticeable, converting anything over 24 MP does take quite a bit of time. Add the option of generating 1:1 previews on top of that process and I could be sitting and waiting for a while in front of my computer before I can finally start post-processing images. Keep in mind that DNG conversion is not a simple process – the DNG converter must not only copy and generate EXIF data, but it also must generate a JPEG preview to save into the DNG file, if you choose to do so (and it is always a good idea, since images can be previewed quickly). Depending on the size of the file and its resolution, this could take a long time, especially if you are dealing with thousands of images.

2) Disk Space Concerns – Does DNG Really Save Space?

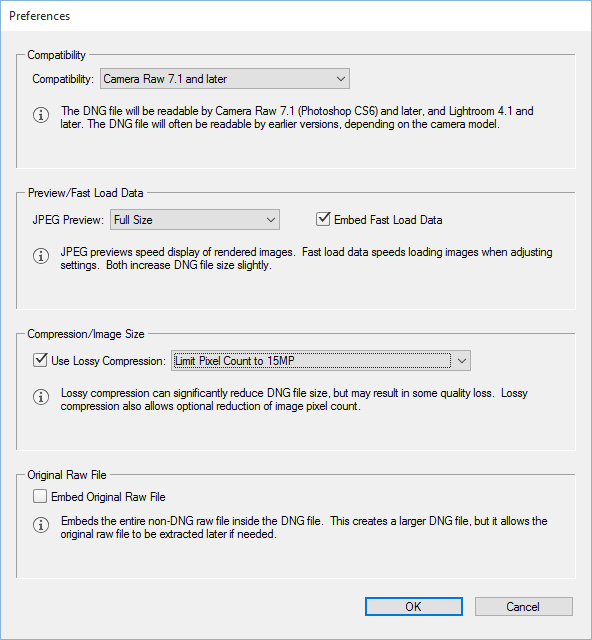

The DNG format is a lot more versatile than a RAW file, because it allows you to tightly control the RAW file conversion process and specify conversion options. When dealing with uncompressed RAW files, DNG certainly does save a lot of space by converting huge uncompressed RAW files to losslessly-compressed RAW files. This alone can result in 50% or more in space savings. In addition, there is an option to generate smaller JPEG previews, which results in additional space savings. And if you do not need full-resolution DNG files, there is even an option for lossy compression, with the ability to limit the total megapixel count. So you could potentially save a lot of space by using the DNG format, provided you fully understand the implications of such things as lossy compression and down-sampling.

However, if you are smart about your camera settings, the space savings offered by the DNG format are more or less insignificant. There is no reason why you should ever shoot uncompressed RAW in your camera, so just don’t – always use the lossless compression method instead. If you do that, the space savings from DNG compared to RAW will be minimal. I did a test run with NEF images that I converted from my Nikon D810 to DNG. With medium-size JPEG previews, the space savings amounted to less than 15% and when I rendered full-size JPEGs, that number got reduced to 10-12%. Given the cheap cost of storage today, these numbers are not something I can be really excited about, especially considering my wasted time converting those images and taking into account all the other disadvantages of the format mentioned in the article.

3) Limited DNG Format Compatibility

Although Adobe has been pushing hard to make the DNG format open and widely adopted for many years now, it seems like very few companies actually give a damn about DNG. Aside from a couple of companies like Leica, Ricoh and Samsung, all the big boys like Nikon, Canon, Sony, Panasonic, Olympus, Sigma and Fuji continue ignoring DNG and pushing their proprietary RAW formats. And the list of DNG “ignorers” is not limited to camera manufacturers – most post-processing software packages out there either do not read DNG at all, or read it poorly, making DNG a lot less useful than it was designed to be in the first place. If you open a converted DNG file in anything other than Adobe software, you might find yourself dealing with excessively slow rendering time, odd colors, inability to read metadata and all kinds of other issues. Of course this is all not Adobe’s fault, which has provided plenty of documentation on DNG, made it royalty-free and even proposed DNG to be controlled by a standards body, if needed. But it turned out that other companies simply did not believe in the DNG format having as bright of a future as Adobe believed it would have, so support for DNG has been quite limited as a result.

Hence, at this point of time, you would be locking yourself to Adobe products if you utilize the DNG format, as others provide limited to no support for it.

4) Processing DNG with Other Software

One of the main reasons why I moved away from DNG back to RAW files is compatibility. Most software out there either has limited support for DNG, or it cannot properly read DNG files at all.

And this includes metadata – although Adobe keeps telling us that all the original metadata is fully preserved, other software engineers did not properly implement a way in their software to read that embedded metadata. I have yet to see a software package that can read all the original RAW metadata such as picture profiles, lens corrections and other data from DNG files properly. The funny thing is, even Adobe itself does not want to mess with all that metadata in its Lightroom and ACR software! If they did, you would not have to keep switching those camera profiles or applying color, sharpness and other adjustments to images. So if Adobe itself cannot do it, how would others with much more limited resources? RAW files already tons of proprietary metadata to begin with (some of which is sometimes encrypted) and you cannot even obtain proper documentation from manufacturers on how to read it. In fact, manufacturers are so reluctant in providing proper documentation with their RAW files that software companies have to reverse-engineer the process of reading and demosaicing RAW files.

As a result, pretty much the only software that can read all that proprietary metadata is provided by the manufacturer, such as Nikon’s Capture NX or Canon’s DPP. And none of the manufacturer software is capable of reading DNG files, yet alone properly extract and read the metadata from those Adobe-converted DNG files!

5) Point of No Return

Once you convert to DNG and wipe out your original RAW files, you are at a point of no return – there is no way to convert a DNG file back to the original RAW file. Adobe gives an option to embed the original RAW file into DNG files upon conversion, but that is an absolutely pointless option, as you will end up wasting a lot of space as a result. So you will have larger files than you started with, making the DNG format even less appealing.

Why might it be important to keep your original RAW file? If you ever wanted to switch from Adobe to any other software package, you would be better off with your original RAW files instead of DNG. There is always a chance that the software you want to use might not work with DNG properly, or in the case of manufacturer software, there might be no support for DNG at all. What are you going to do in such cases? I experienced this first hand when experimenting with other software, some of which either could not read DNG at all or could not read it properly.

6) The Future Compatibility Myth

We have been previously told by Adobe and other DNG supporters that the DNG format would be the format of the future, which gets rid of proprietary RAW files and simplifies them all to a single, open format. In addition, we have been fed with arguments like “your current RAW file may become unreadable some day in the future”. Well, the whole “compatibility” argument and inability to read RAW files in the future are myths for several reasons. First, post-processing and conversion software we see today does not just drop support for older cameras and their proprietary RAW formats. In fact, I have yet to see any software seize support for old RAW files – all that typically happens is newer cameras are added to the list of supported cameras. Why would anyone drop support for something they have been historically able to do well? No company wants to hear complaints from angry customers that are using very old gear. And it is not like the code for reading old RAW formats is so huge and complex that companies need to get rid of the old ones to make space for new ones. Hence, I would not be concerned with software not being able to read your RAW files in the future.

The only case where there might be a legitimate concern, is if one relies on manufacturer’s software to convert RAW files. If a camera is really old, older manufacturer-provided software might not run on newer operating systems. If manufacturer refuses to provide support for newer operating systems, it would be somewhat difficult to go back and run an older version of the operating system just to be able to run the software. It is possible, but would require some effort. There are workarounds though – one could always use third party software, or even revert to Adobe’s DNG converter in the future, if there is no other option.

The above are the reasons why I personally abandoned DNG. If you actively use DNG and convert your RAW files, I would love to hear your thoughts on this article.

For the past 10+ years I have converted all my Nikon nef files to Adobe dng and deleted the original nef’s. My belief is that one day after I upgrade to a new PC with new operating system I will find that when I try to open an old nef, it will not open.

I still believe that a 10+year old dng file has a far greater chance of opening with a new PC with new operating system than does a 10+ year old nef file!

I have been stung previously with a “Microsoft works” database that I can no longer open on current Microsoft software.

I MUST use the NEF to DNG conversion as I have a D810 and PS CS6 standalone. The NEF files are not compatible with this version, thus the DNG requirement :-(

I have been using a D810 and D850 since they were available and CS6 standalone instead of CC software. Until the last update of CS6, the NEF file was readable, but that changed with the final update. I found that the easy work around was to use Lightroom to open my NEF files and do some of the upfront adjustments (or not) and then select EDIT IN PHOTOSHOP. CS6 took the Lightroom generated copy and allowed me to do all of my work with layers or other editing. At the same time CS6 saved the finished edited photo in DNG format for later use by Adobe or publishing software. From a storage point of view, I only have the additional DNG files of a far lower number of selected photos and they are filed side by side with the NEF file.

DNG means order and saving space, it wins.

As a pentax user I don’t have this problem. It saves to dng natively Without silliness like encrypted white balance.

It is difficult to justify supporting propitiatory and obsolete file formats just because you want a certain brand of camera. But there appears to be no choice. Raw file formats serve no purpose that benefits the consumer. And we still use low quality JPEG because people are too lazy to install the much superior J2K file readers.

All that is necessary is for the camera manufacture to change the firmware to offer DNG and J2K. Perhaps they could offer Two models to change over.

I wouldn’t hold your breath.

Using a Macbook Pro with older OS (10.7, and 10.12) and my preferred software (iPhoto 9.6.1) does not support NEF RAW files from newer Nikon cameras, but will open DNG files. It dose wipe out all meta data though. I was considering a new Nikon 850, and downloaded some test files to see if my system would be able to use the software I have since apple doesn’t give two F’s about its customers using older systems. I don’t care for the Nikon software, but I will try to see if it will work with older iPhoto etc.

I use multiple cameras across my family and have been using digital cameras since 2000 and do not want to manage the 15 different file formats that would mean, without dng.

In addition, your argument that software companies will continue to support all the (exponentially) increasingly different RAW file formats is a risky one to make. For example, most automobile companies stop making spares for all cars > 10 years old as the cost of support becomes greater than the cost of upset customers. I see no reason why software and hardware companies would take a different approach.

I convert my Nikon nef to dng. I love dng but after reading this article am fearful dng may die out before I do!

Nasim, thanks for a good article. It strikes a great balance of breadth vs. depth and opinion without biased agenda. The article and related respectable discussions are helpful. Rare article properties indeed esp. where art, science, experienced readers, the Internet, and big companies are all at play.

DNG was always a risky move because of the lack of support and now that risk is on. The best way to deal with photos is to ignore file space requirements and the format-of-the-month and do what’s needed to preserve your photos. If your hard drive isn’t big enough to store them all, get a bigger drive. If you can’t afford a bigger drive than you underestimated the needs of your hobby/business.

Once your drive storage is sorted out, the steps below will keep the originals untouched, allow easy flexibility for sharing, and make a copy that can be discovered by your descendants far in the future.

1. Archive original RAWs to offline permanent storage (NAS, tape, online, etc).

2. Import to software for editing.

3. Export as JPGs for easy public sharing.

4. Export as uncompressed 16-bit TIFFs and burn to M-Disc* for multi-generational preservation, per Smithsonian archival best practices.

siarchives.si.edu/what-…ic-records

*M-Disc is an archival optical disc tested by the U.S. military to last at least 500 years. Data is written as physical holes in the disc so it can’t be wiped off or faded. In the far future– when optical drives are long extinct– these discs can be scanned and the data recreated. No drive needed.