Some photographers have no intention of using flash or light modifiers. Sometimes this is because it does not suit their style, but other times, it is because they do not feel comfortable using flash in first place. While we as photographers often love the look of natural light, knowing how to utilize artificial light can be of tremendous value in low-light environments. In this chapter of Photography Basics, I would like to introduce flash photography and go over situations when flash can be worth using.

How Flash Works in Photography

At some level, flashes are simple devices. They light up brightly, illuminating your photo. But there are also a lot of hidden complexities to modern flashes, and you need to have a basic understanding of how flash works if you want to use it to your advantage.

1. Flash Power

The first thing to know is flash power. This is expressed as a fraction, going up to 1/1 (which is full power). For example, your flash may fire at 1/64 power, 1/8 power, 1/2 power, and so on. The more power, the more light that shines in your photo.

Often, flashes achieve their lower power settings not by actually dimming the output brightness, but instead, by using a shorter flash duration. For example, the flash duration at 1/64 power may be a rapid-fire 1/25,000th of a second!

Flashes really can fire that quickly. With a really good flash at a low power, the duration of the flash may be so brief that it could freeze a bullet in its tracks.

Usually, if a flash fires at full power or nearly full power, it will take a couple of seconds to recharge for the next shot. This can be a big factor if you’re doing something like macro or wildlife photography with a flash, where your subject isn’t in one place for long. In those cases, you may want to use a lower flash power so that your recycle times are quicker.

2. Flash Sync Speed

On most cameras, you are limited to using the flash at certain shutter speeds. For example, on a lot of modern mirrorless cameras, you can only use a flash at 1/200th of a second or longer. If you try to use a flash at a faster shutter speed like 1/500th of a second, the camera may not allow you to set those shutter speeds.

That may sound like a surprising limitation, but it is not done out of maliciousness on the part of camera manufacturers! The culprit is the design of the camera’s shutter curtain. At ultra-fast shutter speeds, the shutter curtain acts like a thin slot that moves quickly across the sensor. So, the whole sensor is not being exposed to light at the same moment. If a flash were used, only one segment of the photo would receive the flash, and the rest of the photo would be very dark or black.

Some cameras and flashes allow you to get around this limitation in various ways. For example, features like high-speed sync, global shutters, and leaf shutters can get around the normal flash sync speed limitations.

However, it is often the case that the 1/200th second limit (or whatever it is on your camera) is not actually a big problem. Remember that the flash duration itself is extremely fast, usually in the range of 1/1,000th to 1/25,000th of a second, so you can easily freeze the motion of a fast-moving subject.

The main situation where you’ll run into problems here is when you’re taking pictures outdoors on a sunny day and want to use a flash. In those situations, the sunlight may be so bright that you cannot use a 1/200th second shutter speed and need to use something faster like 1/1000th. This could prevent the use of a flash. A good solution is to use a darkening filter (called a “neutral density” filter) on front of your lens to reduce the amount of light reaching your camera sensor, enabling the 1/200th-second shutter speed again.

3. TTL vs Manual Flash

Just like your other camera settings, flash can be set automatically or manually. In the flash world, this is known as TTL (“through the lens”) versus manual flash.

TTL flash is automatic. It determines the optimal flash power by measuring the actual amount of light that goes through the lens of your camera. TTL flashes achieve this by employing a “pre-flash” right before the photo is taken – this pre-flash does not end up in your photo, but it does send information to your camera about how bright the flash is. The flash then raises or lowers its power so that the photo is the proper brightness.

To adjust the power of a TTL flash, you can use your camera’s regular exposure compensation dial (though this also affects your other camera settings) or the dedicated flash exposure compensation settings on the flash itself. Many photographers who enjoy using a flash prefer to use manual mode in combination with TTL flash. It is a good combination and very versatile.

As for manual flash, that’s probably self-explanatory. In this mode, you select the flash power manually, such as 1/8 or 1/32 power. Usually, manual flash is best if you need absolute consistency from photo to photo, and your flash is staying in exactly the same spot. It can also be useful for avoiding the pre-flash, such as when photographing certain insects that can be scared away by the pre-flash.

4. Front vs Rear Curtain Sync

You have the choice of when during your exposure the flash will fire. To wrap your head around this, it is probably best to envision using the flash in combination with a long exposure of 10 seconds. Is the flash going to fire at the very beginning of that 10-second exposure, at the very end, or somewhere in between?

Normally, it is a choice between firing at the very beginning or the very end. This is the difference between “front-curtain sync” and “rear-curtain sync.”

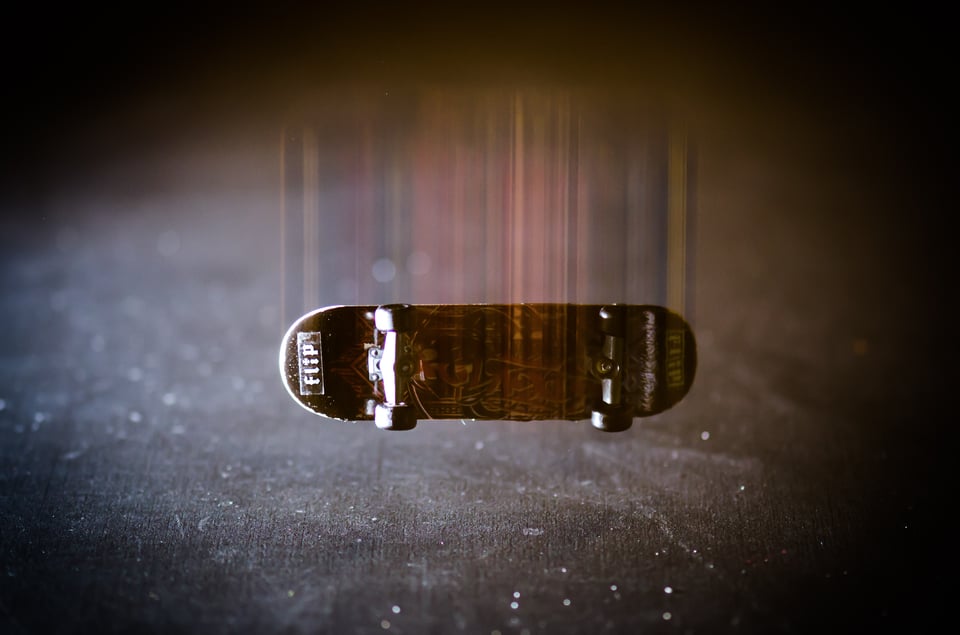

In most cases, rear-curtain sync is preferred. This makes motion in your photo look more natural – motion blur will be followed by a frozen subject, rather than vice versa. When I took the photo below, I used rear-curtain sync for exactly this reason.

Shutter Speed, Aperture, and ISO

This one is very quick, but important! When you use a flash, it interacts with some of your other camera settings. But it doesn’t interact with shutter speed, aperture, and ISO in the same way.

- Shutter speed: Your choice of shutter speed does not affect how bright the flash appears in your photo. That’s because again, the flash only fires for a brief fraction of a second. Whether your shutter speed is 1/100 second or 100 minutes long, the impact of the flash will not change. (Although the brightness of any ambient light will.)

- Aperture: A wider aperture means a brighter photo, including from your flash.

- ISO: A higher ISO means a brighter photo, including from your flash.

You can get away with using a lower flash power if you use a wider aperture or a higher ISO, but the same is not true of changing your shutter speed.

Quality of the Light from a Flash

If you don’t do anything to modify the flash, you will typically get very harsh light with sharp-edged shadows and almost a “deer in the headlights” look. It is occasionally useful for very punchy photos, but usually is not a very appealing look. Luckily, there are a few ways to improve the quality of light that your flash produces.

1. Flash Modifiers

The biggest reason why flash light can look bad is that the source of light isn’t big enough. In photography, the light grows softer when the size of the light source grows larger (relative to the size of your subject). A small flash simply cannot produce soft light unless your subject is microscopic.

However, it is very easy to modify your flash so that it is much softer. There’s a whole industry around flash modifiers! Most flash modifiers are variations on diffusers, which soften the light.

Some diffusers attach directly to the flash and spread out the light. Others are umbrella-shaped diffusers that you fire the flash into. And at a very basic level, a diffuser could even be the wall or ceiling of a room! Fire your flash upward, and suddenly the entire ceiling will flood your photo with soft light.

This only touches the surface of flash modifiers. Some modifiers even do the opposite and create a spotlight effect! Suffice to say that if you’re interested in flash photography, flash modifiers will become an essential part of your kit. But the exact modifiers strongly depend upon the types of photos you intend to take.

2. On-Camera vs Off-Camera Flash

Another way to improve the quality of light as a flash photographer is to take your flash off-camera. This can be accomplished by giving your flash to a friend or assistant, or by using light stands to hold the flash.

Off-camera flash is not always practical unless you’re in a studio environment, but it can really improve your flash game if you’re willing to put in the effort. Photos look best when lit from a variety of different directions, like overhead lighting, backlighting, or sidelighting.

To use an off-camera flash, you need a way to sync the flash to your camera so that they fire when you take the photo. The most common method is to use a radio transmitter and receiver. The transmitter goes on the flash, and the receiver goes on your camera. You can also use optical flash triggers, or even wired flashes, but these typically have more downsides in flexibility and distance.

Finally, one more benefit to shooting with an off-camera flash is that it opens the path to using multiple flashes at once. This can give you even more flexibility in how your photos turn out. While it’s usually best to start flash photography with just a single flash, there is a good chance that you will eventually grow to want a multi-flash setup.

Indoor Flash Photography

High-end cameras may be flexible enough to capture decent images in poorly lit environments, but it is a game of compromises. Using a flash can elevate the quality of your indoor photos substantially.

1. Lighting Ballrooms, Churches, Wedding / Corporate Reception Areas

Most indoor spaces have less-than-ideal light, including wedding venues and corporate reception areas. The goal with flash is to create a primary source of light that is brighter and more pleasant than the dim ambient light.

So, what is the basic setup? First, make sure the venue is okay with flash photography. Then, if you have white ceilings that are not too high, you can mount flash on your camera and simply bounce light off the ceiling or nearby white walls. If the walls / ceiling are of different colors, I would not recommend to bounce flash, though. Light will assume the color of whatever it hits, and green walls will create a green skin tone on your subjects!

Aside from bounce flash, a more complex setup involves putting a diffuser on your camera to soften the light a little, or using an off-camera flash with a diffuser. An off-camera flash setup is ideal from the quality of light. For example, shooting through an umbrella can create great photos indoors. However, off-camera flash setups are not very portable, so they are mainly used in studios or for posed shots, rather than for capturing fast-paced events.

2. Photographing Details Indoors

If you are an event photographer, part of your job is to photograph details for vendors who made that particular event happen. The vendors will vary and include things like florists, bakers, and so on. As an event photographer, you are expected to capture those details well.

In terms of flash, working with stationary items is much easier, since they do not move or talk! Usually, they are also much smaller, which makes it easier to capture them with soft light. (Remember that the softness of the light is determined by how large your light source is relative to the size of your subject.)

For this purpose, a flash on top of your camera bouncing off a white card might suffice. But you can go a little more complex with off-camera flash for a more balanced and professional look. A good two-light setup would be a diffused flash illuminating one side of your subject, and a low-power “fill flash” on the other side to keep the shadows from going too dark.

Outdoor Flash Photography

Most photographers do not bother with flash outdoors. I love natural light! On a sunny day, you can put your subject in the shade and capture a bright, beautiful background behind them. Even on a cloudy day, it is like having a giant diffuser overhead. Not to mention if you are photographing late in the afternoon or at sunset, when the light is as gorgeous as it can get. But flash photography is actually a very valuable tool even in these situations!

1. When Your Subject is Poorly Lit

As the day progresses, your camera will start struggling to keep up with the available light. You will need to start thinking about using alternative light to get the job done. Much like photographing indoors, you may need to expose your subjects with an artificial light source.

The considerations here are similar to what they were for indoor photography. You are relying on the flash to provide most of the light in the photo, so you need to make sure that it is as soft and beautiful as possible. This means using a diffuser and off-camera flash if possible. The good news is that outdoors, you will often have more space to set up some light stands in your preferred spot.

2. Fill Flash When Shooting Backlit

You can get some very cool photos outdoors with a flash by positioning your subject with the sun behind them. Normally, they would show up as a silhouette, but a flash can bring back those details and give you a well-exposed photo.

While you could use a basic reflector in these situations (and potentially an assistant for holding it), fill flash can do wonders, too. I usually use one medium size umbrella or a softbox on a stand to do the trick.

3. Fill Flash to Avoid Harsh Shadows

You might think that a sunny day would be the last time a flash could be helpful. But it’s actually one of the best times to use a flash! If you’re taking pictures with the sun directly overhead, you will get very harsh light on your subject. While some gorgeous photos can be taken in harsh light, it usually is not flattering for portrait photography. You can end up with ugly shadows on people’s faces and “raccoon eyes” that just don’t look right.

A flash can solve these problems. Using a diffused flash on low power, fire the flash toward any shadows that look too harsh. This is one case where on-camera flash works pretty well, since the flash is not the main source of light in the photo – it is just filling in the shadows. I constantly use flash for outdoor photos in daylight, and I recommend that you do, too!

4. Counteracting Color Casts

One problem that often comes up with outdoor photography is the presence of color casts. For example, if you place your subject next to some beautiful green plants, some of that green color will reflect onto your subject’s skin!

Fixing this after the fact can cause a lot of hassle during post-processing. Although there is no cure for it in the camera, you can reduce this effect by using a fill flash (along with an umbrella, softbox or other modifier) to illuminate your subject. This will help isolate your subject from the surroundings and reduce color reflections. You can even attach a “color gel” to your flash to change the flash color in subtle ways.

On a similar note, you can use flash gels to change the colors more dramatically in your photos if you want! This applies both in the studio and outdoors. It’s possible to take some very interesting photos with unique colors thanks to your use of a flash. Always make the time to be a little creative at any event that you photograph, and you could end up with some very good photos as a result.

I hope that gives you a good idea of how flash works in photography! Now you’re nearing the end of our Photography Basics guide, just two more chapters left. You can jump to those articles below.

Download as an eBook

I’ve received many requests over the years to download Photography Basics for offline viewing. As of 2025, I’m excited to announce that I now have a dedicated eBook version of Photography Basics! The eBook covers the same information but is optimized for offline reading/printing, with a beautiful design and updated text. Photography Life members get this eBook included with their membership ($5/month, cancellable any time) alongside a lot of other benefits – including a Q&A group if you have questions about the topics I’ve covered in these articles. You can read more information about our memberships here.