One of the more common exposure tips in photography is called the sunny 16 rule. Although it dates back to the early days of photography, and some would argue that it is obsolete at this point, most photographers still hear about this rule while learning about exposure. So, what is the sunny 16 rule, and does it still matter for taking pictures today?

Table of Contents

Introducing the Sunny 16 Rule

The sunny 16 rule is a simple way to determine a good exposure for a photograph. On a clear, sunny day, when you are using an aperture of f/16, this rule recommends a shutter speed equal to the reciprocal of your ISO (1/ISO value).

At ISO 100, for example, use a shutter speed of 1/100th of a second. At ISO 200, use a shutter speed of 1/200 second. That’s all there is to it.

Keep in mind that all the various exposure settings recommended by the sunny 16 rule are not equally worthwhile, even on a sunny day, and the rule itself doesn’t claim they are. For example, you probably will not want to shoot at settings like f/16, ISO 3200, and 1/3200 second for many photos.

Instead, the sunny 16 rule is all about providing a quick set of exposure settings which will result in a photo of the proper brightness. You still need to pick from those settings to determine which one is ideal for the scene you’re capturing.

Also, it is easy to expand the sunny 16 rule further by assuming a different aperture value or a darker scene. For example, if the settings f/16, 1/100 second, and ISO 100 provide a bright enough photo on a sunny day, the same will be true for f/11, 1/200 second, and ISO 100 in the same conditions. That still counts as a “sunny 16 exposure,” even though you’re at f/11. These numbers are meant to be shifted.

Does the Sunny 16 Rule Work?

Although the sunny 16 rule can work as a general guideline, you will find situations – even on clear, sunny days – in which it leads to underexposure or overexposure. The colors and reflectiveness of your subject make a big difference here, and so does the direction you face (into the sun, or away from it). If your standards are too high, the sunny 16 rule plainly does not work.

However, it never was meant to be a precise way to find your optimal exposure – simply a guideline to help you down the right path. By following the sunny 16 rule, you immediately know a range of camera settings that will be roughly correct, and you have the ability to bracket or consult your meter to refine things more precisely.

What About Your Camera’s Meter?

Most photographers don’t use the sunny 16 rule for their daily work. Instead, they use the camera’s own meter to find a good exposure, adjusting exposure compensation as needed. That’s probably what you should do as well.

The sunny 16 rule isn’t better than your meter in most cases. Originally, it was used as a way to calculate exposure if you didn’t have a meter with you, or to serve as a sanity check on your meter’s reading (since you couldn’t just review a photo you had taken with film).

Today, essentially every digital camera on the market has a built-in meter, and you can review your photos immediately to judge exposure (as well as consult tools like your histogram for greater precision). So, the sunny 16 rule is a bit of a relic. It is rarely used in the field any longer.

However, that does not mean this rule is useless. Personally, I believe that you can improve your photography skills by forming a deep, intuitive understanding whenever you learn about an important topic like exposure. In this case, the sunny 16 rule helps you learn an instinctive range of reasonable settings for a scene even before you decide to take a photo.

In other words, the sunny 16 rule is a good starting point to formulate your own “mental meter” if you have not begun to do so already. It is also a useful way to teach beginning photographers about the concept of exposure – how your camera settings relate to one another, and to the scene you are photographing.

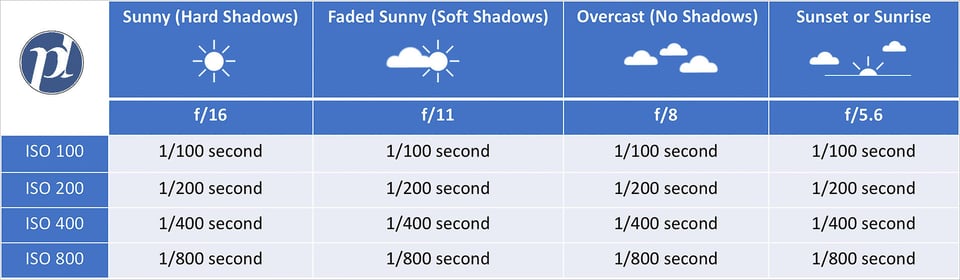

Sunny 16 Rule Chart

Below, you will find a chart with the sunny 16 rule’s recommended exposure settings. This chart also includes the equivalent exposures for darker scenes:

Note that these values are not precise, and, again, the optimal exposure depends upon a number of additional factors. It is important to check your camera’s meter reading if you want a more specific suggestion for exposure. Also, the chart above does not cover all the potential settings which will work for a given scene. (You certainly can take high-quality photos at sunset at f/11, for example.)

Conclusion

The sunny 16 rule is not the optimal way to capture a good exposure. It is not even a technique, most likely, that you will need to think about at all in the field. Useful tools like your camera’s built-in meter, histogram, and blinkies have rendered basic tricks like this generally obsolete in today’s world.

However, for photographers who are trying to expand their personal skillset and intuitive understanding of photography, the sunny 16 rule still has value. There is something to be said for refining tools like your “mental meter” and visualization skills if you want to become a better photographer. It also helps beginners understand the relationship between a scene’s appearance and the camera settings needed to capture it successfully.

So, there are at least a couple good reasons why the sunny 16 rule has lasted until today (aside from old habits dying hard). Hopefully, this article helped you determine whether or not it will be useful for your photography as well.

Great article, thank you for posting. Question: I’m shooting w. the Nikon F4s w 400 ISO film. I can only dial in a 250 or 500 shutter speed. Any recommendations?

This is the simplest explanation I have read so far. I’m not a beginner by any means. I have benn into photography for at leas 30 years. However the Sunny16 rule seems to escape me most of the time. I just can’t remeber it when I’m out in the field with no meter. This time I hope it sticks, thank you/

Thank you Spencer. I like to comment some more and answer some questions as well, if you permit me so. And again thank you for the wonderful article of yours!

Tommy, I use f/11.

Harvey, My old rangefinder camera suggest f5.6 apperture for a full overcast.

What concerns the geolocation – we live in Finland which is quite on the North and sunny 16 rule works perfectly. So far it is the only way to capture dertails in the skies for sure without washing skies out in white. It seems it does not really depends that much on where you live, though the sun must be high enough. When sun goes down, one need to add to exposure.

WHY SUNNY 16? Using this rule is possible to gather details in bright area of the image without problems in general. However objects in shadows may and will suffer from lack of light. (The lattitude of the camera is much narrow than human eye and gamma is different. Human sees 18 percent white as 50% white because of the human eye responce to darker areas is not being linear!) If you photograph landscapes on a wde angle lens then above mentioned issue it is not a problem at all. However, would you like to zoom in to some object (under condition there is no skies in the image), you will find out that it requires some more light, usually about one full stop to expose the scene corretcly and still maintain natural look.

Example, typical scene 24mm 1.5 crop, bright blue skies, deep blue whater, snow, some trees, sun is somewhere behind and no clouds, 2pm. Sunny 16, perfect shot, but some shadows may appear too dark, that can be corrected in RAW processing but not a problem for wide angle shot to leave it as is. The atmosphere is recorded successfully.

Zoom in on water with swans, 120mm. One stop extra. Scene looks brighter and more appealing for eyes. Snow is bright but still ok. No sky in picture or it would wash out.

maybe I can write later independent article on the exposure compensation with sample shots.

Spencer, Modern Nikon cameras use color matrix metering system, which is unlike older fashion metering system does not have the issue with black and white subjects. You can rely on this if your concern is the subject you photograph and not the landscape. Generally meterring system of most recent and expensive cameras is quite accurate unless you have sun reflections or sun rays getting into the scene toward you. Then and when you shot landscapes you better go Manual.

To RULE or not to RULE? IMO, it is much more simpler to adapt to Natural condition and learn to compensate plus/minus 2 stops than trying to adapt to the metering system of your cam and (again) trying to guess the compensation values for it’s AI algorithm, which will change from one model to another. In the best scenario, camera (latest and expensive model) gives you 80% of success and you will be able to compensate as much as 10. Intuition gives you 95% of success +5 with some metering and braketing. Learning curve is fast, believe me, just give it a try.

Metering in MANUAL? Or hot to learn use M mode? M mode has a scale in the viewfinder where you can see the in-camera metering system’s recommendation. Set metering to spot meter and try to move the spot area around the scene. If all ther objects are inside of plus/minus 2 stop zone, then ou would succeed. If there are some brighter or darker objects/areas in the scene, then you have to think on composition and sacrifice on something. Remember it is reflective metering and final results will be little bit different, so you still will be able to succeed and gather shadow details from the RAW image!

How to be 100 procent sure? Well, set 5 braketing shots and fire a sequence of five every time. It will work for digital, but if you shot on film, better learn the Sunny 16 rule and be successfull with it. If in doubt, check spot meter from the sky just above the horizont in direction of North. It will replace the gray card. For VERY important “a million dollar” shots use BRAKETING as a rule.

Remember that a million dollar image is either CAREFULLY planned or SPONTANEOUS image you would not be able ever to repeat.

To compensate or to not? Think, what you prefer, a “perfect” or the Natural exposure. Many shot on Automatic white balance. Try Sun light balance. Answer, must it be evening blue moment as bright and white as the day shot or it shall look as you have seen it, little bit darker and bluesh, otherwise natural.

And, finally, WHICH METERING to use? Incandescent metering gives natural results and is superior but not always possible. Metering from skies above horizont, is reflective metering, but it works. Metering from gray card installed in the scene or from gray rock is reflective and it works too.

When I photographed on slides I was using only Sunny 16, Manual exposure, spot metering and graycard or horizont metering. It worked always. Hope it helped.

I wanted to mean – incidental light metering, not incandescednt :)

Diffraction sets in. f/16 not very usable in digital age.

I would just add that for those of us who use, or have used, low-end Nikons which do not meter at all with manual lenses, the sunny 16 rule is a very handy thing. Of course you can look at the histogram after a shot, but it’s good to have a place to start, and it’s often right anyway.

In some scenes like snowscapes, where the average is not gray, it may be a better guess than the meter’s, and closer to the ambient light.

Thank you! I had forgotten about this.

Thank you so much.

Normally I used to the sunny 16 rule in my photography.

This took me back to when I was learning photography as a teenager and I used to carry film boxes with this sort of info printed, I remember having one with some handwritten corrections based on my own experience and perception/taste!

Now I’m curious to test it on my Fujifilm gear and that got me thinking about something I’ve read over and over about Fujifilm’s sensor… The native ISO is 200 and not 100… With many websites competing Fuji’s ISO 200 to other cameras in the market ISO 100.

Would that be the case of adapting the rule?

ISO 200 > SS 1/100

ISO 400 > SS 1/200

ISO 800 > SS 1/400

ISO 1600 > SS 1/800

I know someone on this website shoots Fujifilm, maybe that’s a question for that person ;-)

Thanks for the great article! Keep them coming!

Hi Spencer,

Your well written article took me back to the mid 1960 years when I became the proud owner of a Halina camera.

Black and white films in metal canisters, inside small valuable boxes, when opened contained the Sunny 16 Rule Charts for the specific ASA of the film.

Still remember judging the ” amount ” of light available. The aperture of the Halina needed to be set first then then visually calculate the distance to set the focus. Done in the wrong order messed up the sharpness of the photo.

Our modern equipment came a long way but the Sunny 16 still lurks somewhere in my thoughts.

Thank you so much.