One of the biggest challenges in photography is sharp photos when hand-holding a camera. Many end up with blurry images without understanding the source of the problem, which is usually camera shake caused by basic improper hand-holding techniques or mirror and shutter-induced vibrations. The easiest way to compensate for this shake is to use the reciprocal rule, which tells you the minimum shutter speed that you should use.

That’s because the most common cause of camera shake is lower-than-acceptable shutter speed when hand-holding the camera. I will introduce and explain the reciprocal rule, which can help in greatly increasing the chances of getting sharp photos when you do not have a tripod around.

Sony A7R + FE 35mm f/2.8 ZA @ 35mm, ISO 100, 1/40, f/11 © Nasim Mansurov

Table of Contents

What is Reciprocal Rule?

Due to the fact that we as humans cannot be completely still, particularly when hand-holding an object like a camera, the movements caused by our bodies can cause camera shake and introduce blur to images. The easiest way to counter this is:

The Reciprocal Rule: the shutter speed of your camera should be at least the reciprocal of the effective focal length of the lens.

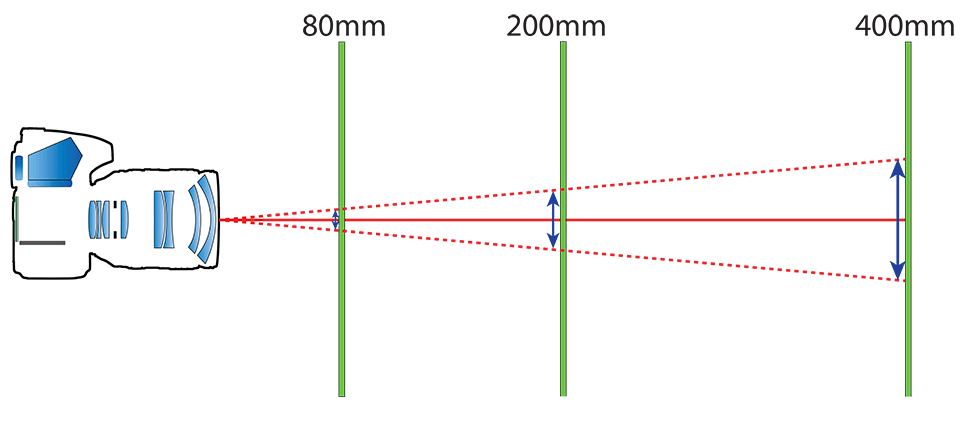

For example, if you are shooting with a 50mm lens, use a shutter speed of at least 1/50. Or, say you are shooting with a zoom lens like the Nikon 20-120mm f/4S lens on a full-frame camera. Now the rule says that if you are shooting at 80mm, your shutter speed should be set to at least 1/80th of a second, whereas if you zoom in to say 400mm, your shutter speed should be at least 1/400th of a second.

Using such fast shutter speeds helps prevent blur by camera shake. Why? Because there is a direct correlation between focal length and the effect of camera shake – longer focal lengths magnify camera shake. If you have a zoom lens like the above-mentioned Nikon 24-120mm lens, you have probably already noticed how much more shaky and jumpy your viewfinder looks at 120mm, compared to 20mm. That’s because camera movement is magnified at longer focal lengths:

The Reciprocal Rule and Motion Blur

Camera shake is not motion blur. In other words, blur caused by camera shake is very different than motion blur (where the subject is faster than set shutter speed).

Motion blur typically happens when your subject is moving. In this case, even if you use the reciprocal rule, you still could get a blurry shot because your subject is moving very fast. For example, most birds in flight need at least a shutter speed of 1/2000 on a 500mm lens, whereas the reciprocal rule only recommends a minimum of 1/500.

It is also important to point out that the reciprocal rule only applies when hand-holding a camera. If your camera is on a sturdy tripod, then it is not shaking and so the reciprocal rule isn’t necessary.

Effective Focal Length

Please note that I used the word “effective focal length” in the definition and gave you an example with a full-frame camera. If you have a camera with a smaller sensor than 35mm or full-fame, you first have to compute the effective focal length, also known as “equivalent field of view”, by multiplying the focal length by the crop factor.

Example. If you use the same 80-400mm lens on a Nikon DX camera with a 1.5x crop factor and you are shooting at 400mm, your minimum shutter speed should be at least 1/600th of a second (400 x 1.5 = 600).

This is just an approximate rule of thumb, and it is used because crop sensor cameras often have higher pixel densities than full-frame cameras, so they show camera shake more readily. Of course, if you have a 50MP full-frame camera, it will show more camera shake at the pixel level than a 24MP full-frame camera, so it might be wise to also apply this rule for high-density sensors if you are a pixel peeper.

Exceptions and Notes to the Reciprocal Rule

Although it is commonly referred to as “reciprocal rule”, it is not a rule per se but rather just a guidance for minimum shutter speed to avoid blur caused by camera shake.

In reality, how shutter speed affects camera shake depends on a number of different variables, including:

- The efficiency of your hand-holding technique: if you have a poor hand-holding technique, the reciprocal rule might not work for you and you might need to use faster shutter speeds. Gear and lenses vary in size, weight and bulk, so you might need to utilize specialized hand-holding techniques depending on what you are shooting. For example, check out this great article by Tom Stirr on hand-holding techniques for telephoto lenses.

- Camera resolution: Cameras today like the Nikon Z9 have more pixels crammed into the same physical space. Higher resolution cameras will show more intolerance to camera shake than their lower resolution counterparts. So, if you are dealing with a high resolution camera, you might need to increase your shutter speed to a higher value than what the reciprocal rule suggests.

- Lens quality / sharpness: you might have a high resolution camera, but if it is not matched by a high-performing lens with great sharpness, you will not be able to yield sharp images, no matter how fast your shutter speed is.

- Subject size and distance: photographing a tiny bird from a long distance and wanting to have every feather detail preserved usually requires faster shutter speed than recommended by the reciprocal rule, especially if the subject needs to be tack sharp at 100% zoom.

Do You Need the Reciprocal Rule with Image Stabilization?

Most mirrorless cameras today come with image stabilization. Even if you are using a DSLR, many longer lenses have optical stabilization built-in!

The ceciprocal rule is often too conservative if your lens or your camera come with image stabilization (also known as “vibration reduction” or “vibration compensation”), because it effectively reduces camera shake by moving internal components of a lens or the sensor of the camera.

Modern image stabilization systems these days give between 4-7 stops of stabilization. And if you’re getting say, 5 stops of stabilization, that means that on a 100mm lens, instead of needing a shutter speed of 1/100, you might only need a shutter speed of 1/3! Of course, that assumes that your subject isn’t moving, because even slowly-moving subjects like turtles will cause blur at such low shutter speeds.

To take another example, the 80-400mm f/4.5-5.6G VR comes with image stabilization up to 4 stops of compensation, and so you could theoretically reduce the recommended shutter speed by reciprocal rule by up to 16 times!

So when shooting at 400mm, if your hand-holding technique was perfect and you turned image stabilization on, you could go from 1/400th of a second (reciprocal rule based on a full-frame camera) to 1/25th of second and still be able to capture a sharp image of your subject (provided that your subject does not move at such long shutter speeds and cause motion blur). In such cases, reciprocal rule simply does not apply.

If you’re relying on in-body image-stabilization (IBIS), remember that it loses effectiveness at longer focal lengths. So, if you are using a camera with IBIS but your lens does not have in-lens stabilization, then you might not want to forget the reciprocal rule so quickly.

Applying Reciprocal Rule: Auto ISO

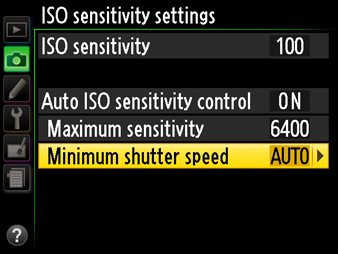

Many of the modern digital cameras come with a really neat feature called “Auto ISO“, which allows one to let the camera control camera ISO depending on light conditions. Some Auto ISO implementations are rather simplistic, letting the end-user specify only minimum and maximum ISO and giving little to no control on minimum shutter speed. Others will have more advanced Auto ISO features, allowing to specify not only ISO ceilings, but also what the minimum shutter speed should be before ISO is changed.

Nikon and Canon, for example, have one of the best Auto ISO capabilities in their modern mirrorless cameras – in addition to the above, minimum shutter speed can be set to “Auto”, which will automatically set the shutter speed based on the reciprocal rule:

One can even customize this behavior further, by changing the minimum shutter speed relative to the reciprocal rule. For example, on my Nikon D750 I can set the minimum shutter speed to “Auto,” then set the bar once towards “Faster,” which will speed up shutter speed based on the reciprocal rule.

So, if I am shooting at say 100mm focal length, the camera will automatically increase ISO once my shutter speed reaches 1/200th of a second. And if I use a stabilized lens and want my camera to have a longer minimum shutter speed, I can move the same bar towards “Slower,” using a longer minimum shutter speed guided by the reciprocal rule.

Of course, if you have set a minimum shutter speed, make sure to turn it off or switch to another mode when you don’t need it, such as when you are shooting on a tripod.

The Reciprocal Rule for Different Genres

The reciprocal rule is useful, but there are certain genres of photography where you still have to be careful and use a bit more planning instead of just relying on the reciprocal rule for your photography.

Landscape Photography

Landscape photography is often done on a tripod, so in dimmer light, it’s much better to set your camera to its base ISO and let the shutter speed be as long as possible.

Even if you’re not on a tripod, landscape photography often uses wider focal lengths, which are especially effective with IBIS in mirrorless cameras. So in many cases, you might not need the reciprocal rule. If you are shooting handheld with a DSLR, it’s still good to use the rule, however.

Portrait Photography

The reciprocal rule works well with portrait photography, where you are using longer focal lengths and natural light. However, portrait photographers often use flash.

In this case, if the majority of your light is coming from flash, then you can shoot at whatever shutter speed is required for the effect you need: a much lower shutter speed to “drag the shutter” if you want background light in, or a higher shutter speed of 1/200 to use only the light of the flash.

Wildlife and Sports

In wildlife in sports, your subject is typically always moving. In this case, you’ll pretty much always need to use a higher shutter speed than recommended by the reciprocal rule.

Macro

At close-up distances in macro photography, forget the reciprocal rule. The high magnification simply…magnifies camera shake! Thus, even with short focal lengths like 50mm, you still might need a higher shutter speed than 1/50 to get sharp shots, simply because you are so close!

A lot of macro shooters use flash because of this. Even if you can handhold macro shots, it still might be better to use flash because there is so little light in macro.

Conclusion

Even with today’s advanced cameras, the reciprocal rule is still useful, especially in those cases where you don’t have stabilization on your camera or on your lens. Even if you do, there ar some cases such as very long focal lengths where it can come in handy. Finally, remember that the reciprocal rule just recommends a minimum. You may still need to use a higher shutter speed for other reasons such as moving subjects.

Do you still keep the reciprocal rule in mind? If so, let me know in the comments!

Superb

Nasim, I have found your articles to be extremely helpful!

Re: “photographing a tiny bird from a long distance and wanting to have every feather detail preserved usually requires faster shutter speed than recommended by the reciprocal rule”. Not sure whether anyone has pointed this out, but that advice is totally backwards. For any specific focal length, the closer you are to the subject, any movement of the camera or subject cause the subject to move across more of the field of view during the exposure.

Frank

“how sharp images turn out at 100% zoom”

This. People tend to miss this. The idea that you need minute sharpness at 100% zoom on your computer screen is quite frankly ridiculous most of the time. People need to think more in terms of printed size or actual viewing size. Let’s say I photograph the same item using a 24MP camera and a 50MP camera using the same settings. At 100% zoom the 50MP picture might show more blur compared to the 24MP picture. But zoom out to have the same viewing size and they will be the same.

The sensor size does not influence the reviprocal rule. If camera shake gives a 1% blur on a Fx sensor, it will also be 1% on the center part or on a DX sensor.

Equivalent focal length is only a cropped field of view and has no pptical property as such.

Jacques

Hi. I’ve read a lot of this now and also about DOF and hyperfocal lenghts. All formulas designed for film and now we have DX and also smaller sensors. So I started wondering what is behind the formulas. I’m not so worried about camera shake, I want to figure out shutter speed for moving subjects.

Imagine a D7100 DX camera on a tripod with a 35mm. An athlete running at 20km/h (12,5 mph) passes from left to right 5m in front of the camera and you fire at 1/1000s. What happens if you see the picture at 100%. The speed of that light on the sensor, is 9700 pixels per second. With 1/1000s you get a 10 pixels blur! If you use a D40 (same sensor size, 1/4 pixels) the blur is only 5 pixels. So focal distance, subject distance, subject speed, angle, sensor size and pixel density all have infulence in 100% zoom pixels inspection.

Usually I would pan the camera following the movement, but the legs of the runner are still moving relative to the camera.

92$/hour@life

>/ < www.NetCash9.Com

Hi Nasim, I was just wondering what difference the use of a teleconverter would make with regard to this guideline? For example, if I have a 200mm lens and a 2x converter, would I need to set the shutter speed to 1/400 with it attached?

Oddly enough we learned different rule known as reciprocity. Reciprocity refers to the rule that an exposure is the same at say f2.8@1/1000th, f4@1/500th, f5.6@1/250th, etc. In the film days this was especially important to know if you did long exposures because films suffer from what’s called reciprocity failure. That’s a phenomenon where film looses its sensitivity in long exposures and that rule breaks down.

I think we learned the rule you refer to as the inverse focal rule. And that only applied to 35mm cameras- it would have made no sense back in the 1980’s with film sizes as diverse as 110 (13x17mm) up to the largest format I ever shot hand held 4×5″ (10x12cm.)

The reciprocal rule is the reciprocal rule – and has always referred to the guidance about shutter speed when hand holding a camera. You may have known it as the ‘inverse focal rule’ but this is mathematically incorrect. I am no mathematician, but reciprocal means to divide by a number e.g. the reciprocal of 500 is 1/500 while the inverse (generally understood to be the additive inverse) is the opposite or negative of a number i.e.the inverse of 500 is -500.

The multiplicative inverse however, does corresponds to the reciprocal! i.e. 1/500.

Then there are reciprocal and inverse trigonometric functions – at which point my schoolboy math gives up and I am lost without trace!

There is an inverse square law, which is a law, (as opposed to a rule or guide), but which has nothing at all to do with camera shake!

Reciprocity failure is not a rule, it is a phenomenon.

It is the way film (and the human eye) behave when exposed to light and varies from film to film (and from person to person).

At ‘average’ values the curve describing the response is more or less linear = twice the amount of light twice the response. At the extremes however, it takes a disproportionately longer exposure to light (or higher intensity) to elicit the same response. Film response is a gamma curve. Digital sensor response is linear.

This is the basis for the gamma curve in photography and explains why we expose differently for digital sensors (ETTR- expose for maximum data) than we did for film (expose for preferred tonality).

The reciprocal rule does not, with respect, only apply to the 35mm format. There are just as many sensor formats today as there were film formats yesterday.

Camera shake is a function of magnification and for a given focal length, magnification is constant. Therefore the reciprocal rule is constant. Only the field of view changes with change of format, not the magnification. To make matters worse, most medium and larger format cameras suffer from horrendous mirror slap so there is an argument for increasing the reciprocal factor to take account of this negative feature.

FYI: I replied to you but needed to include a couple links to Wikipedia and Stackexchange which left my reply “in moderation.” Let me ditch the links and maybe my real comment will be approved eventually.

Here’s what I sent sanitized of links:

Hey Betty,

I think at least some folks see this as I do. As an example this Wikipedia entry on the subject: (search for Reciprocity (photography) on Wikipedia since I guess I can’t put links here)

As for the application to 35mm format in what I know as the inverse shutter speed, format would presumably be a logical measure. Because it would determine angle of view and as such magnification (at least at the same distance.) A super wide lens on 4×5 film like a 75mm (equal to a 24mm in 35mm) would be a moderate telephoto on 35mm or “full frame” digital, and equal to 150mm on 110 film. Obviously the resolving power of a 4×5 film image is immensely greater than that of 110. But all other factors (including resolution) being equal you could get away with a much longer exposure with a big piece of film than a tiny one. That inverse focal rule is truly just a rule of thumb.

Here’s a snippet from a similar discussion I found: “So, I don’t know exactly where it came from, but it’s definitely an idea for 35mm film, and it’s clear that in its early form, it was seen as a general guide, not a law.” (more info here: link removed just look at the search: stack exchange shutter speed focal length rule )

Cheers, -mike

Betty:

There is an additive inverse as you’ve mentioned x and -x;

And there is a multiplicative inverse, also known as the reciprocal as in x and 1/x.

So you’re both correct, just one a little bit more precise than the other.

“The multiplicative inverse however, does corresponds to the reciprocal!”

Isn’t that what I said?

What a delightfully esoteric but irrelevant discussion this has turned out to be.. rather like how many angels can fit on the head of a pin?

Of absolutely no interest to anyone but the protagonists!

The Effective Focal Length chapter is wrong. I think I have told you this before Mansurov.

Consider if you take two images on a d800 and the only thing change is that you take the second one in dx mode. You are saying that the cropped image now magically needed a faster shutter speed. Which of course is wrong since absolutely nothing changed in the physics. Also, since shooting in dx mode is exactly the same as cropping an fx image in the photo editor, you are also indirectly saying that the more you crop an image in editing, the faster shutter speed you should have taken the image with to get the same motion blur as in the uncropped image.

Sensor size doesn’t change either motion blur or ‘reach’.

Normally the whole image or nearly the whole image is used to make the finished photograph (otherwise we’re not optimally using the camera to get the best image quality). The significance of blur depends on the radius of the blur relative to the image dimensions. In most applications, because of limitations in the resolution of the presentation medium, the image is resized to a much smaller pixel dimensions than the original capture. Whether the image will appear soft or not it is usually not necessary to consider the pixel level detail but how easy it is to detect the blur in the final image at the size and resolution it is displayed.

The same is true of depth of field – normally the circle of confusion for DOF calculations is set according to the format size – using larger formats (sensor sizes), the circle of confusion can be larger before the area of the image considered becomes visibly blurry in the final presentation of the image.

Of course, if one is using a small part of the image only (heavy cropping) then the pixel level detail is important and the circle of confusion must be set accordingly, but in that case the image quality will be quite poor, whatever you do. Some don’t care, and that’s their right, of course.

Actually Nasim has said “So if you use the same 80-400mm lens on a Nikon DX camera with a 1.5x crop factor …”,

He did not say ‘changing an FX camera to DX mode’, which, as you rightly point out, will not affect the ‘reciprocal rule’ simply because the pixel spacing (obviously) remains the same.

As Betty pointed out below, the main determining factor of ‘blur’ at the pixel level is due to the spatial distribution of the pixels.

A 24MP FX sensor will have a lower pixel density than will a 24MP DX sensor and thus not exhibit blur to the same extent when viewed at 100%.