Writing an introduction to photography is like writing an introduction to words. Photography is complex, full of variety, and capable of limitless storytelling and emotion.

What separates inspiring photographs from ordinary ones, and how can you improve the quality of your own photos? This article lays a foundation to answer to those questions and introduce you to the concept of photography from the ground up.

What Is Photography?

Photography is the art of capturing light with a camera, usually via a digital sensor or film, to create an image. With the right camera equipment, you can even photograph wavelengths of light invisible to the human eye, including UV, infrared, and radio waves.

The first permanent photograph was captured in 1826 (some sources say 1827) by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in France. It shows the roof of a building lit by the sun. You can see it reproduced below:

We’ve come a long way since then.

This article is the second chapter of my detailed “Photography Basics” guide. My goal in this chapter is twofold: to introduce you to the past and present worlds of photography, and to give you a general idea of the principles that you’ll need to learn as a beginning photographer. Let’s start with a brief history lesson.

A Short History of Photography and the People Who Made It Succeed

Photography is everywhere today, and it can be hard to remember that it wasn’t always that way. Color photography only started to become popular and accessible with the release of Eastman Kodak’s “Kodachrome” film in the 1930s. Before that, almost all photos were monochromatic – although a handful of photographers, toeing the line between chemists and alchemists, had been using specialized techniques to capture color images for decades before. (You’ll find some fascinating galleries of photos from the 1800s or early 1900s captured in full color, worth exploring if you have not seen them already.)

These scientist-magicians, the first color photographers, are hardly alone in pushing the boundaries of one of the world’s newest art forms. The history of photography has always been a history of people – artists and inventors who steered the field into the modern era.

Below, I’ve compiled a brief introduction to some of photography’s most important names. Their discoveries, creations, ideas, and photographs shape our own pictures to this day, subtly or not. Although this is just a brief bird’s-eye view, these are all people you should know before you step into the technical side of photography:

1. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

- Invention: The first permanent photograph (“View from the Window at Le Gras,” shown earlier)

- Where: France, 1826

- Impact: Cameras had already existed for centuries before this, but they had one major flaw: You couldn’t record a photo with them! They simply projected light onto a flat surface – one which artists used to create realistic paintings, but not strictly photographs. Niépce solved this problem by coating a pewter plate with, essentially, asphalt, which grew harder when exposed to light. By washing the plate with lavender oil, he was able to fix the hardened substance permanently to the plate.

- Quote: “The discovery I have made, and which I call Heliography, consists in reproducing spontaneously, by the action of light, with gradations of tints from black to white, the images received in the camera obscura.” Mic drop.

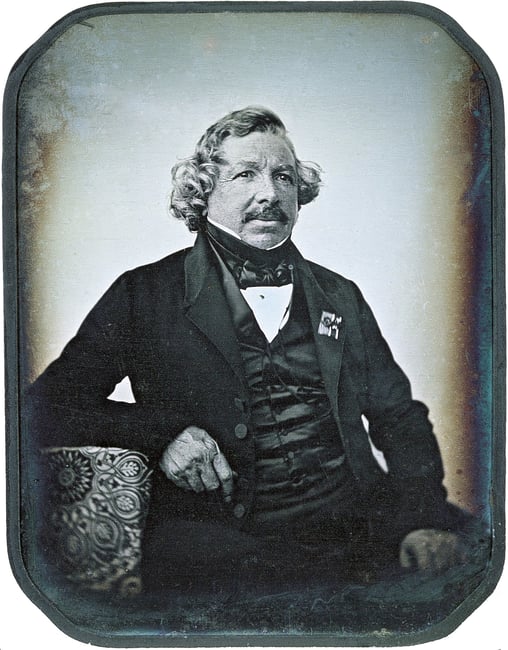

2. Louis Daguerre

- Invention: The Daguerreotype (first commercial photographic material)

- Where: France, 1839

- Impact: Daguerreotypes are images fixed directly to a heavily polished sheet of silver-plated copper. This invention is what really made photography a practical reality – although it was still just an expensive curiosity to many people at this point. The first time you see a daguerreotype in person, you may be surprised just how sharp it is.

- Quote: “I have seized the light. I have arrested its flight.”

3. Alfred Stieglitz

- Genre: Portraiture and documentary

- Where: United States, late 1800s through mid 1900s

- Impact: Alfred Stieglitz was a photographer, but, more importantly, he was one of the first influential members of the art community to take photography seriously as a creative medium. He believed that photographs could express the artist’s vision just as well as paintings or music – in other words, that photographers could be artists. Today’s perception of photography as an art form owes a lot to Stieglitz.

- Quote: “In photography, there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality.”

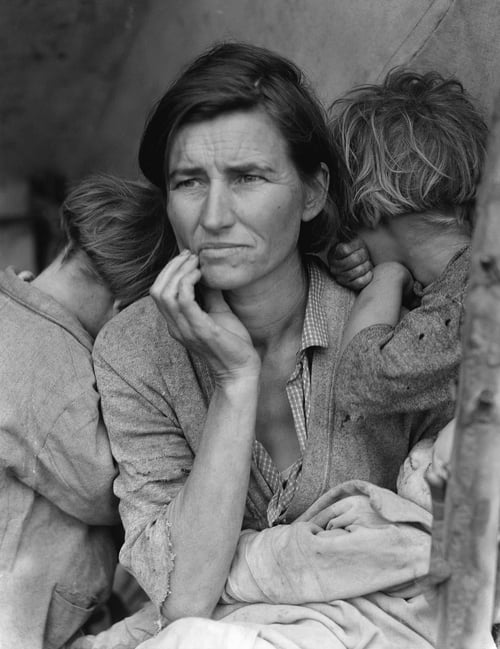

4. Dorothea Lange

- Genre: Portrait photography

- Where: United States, 1930s

- Impact: One of the most prominent documentary photographers of all time, and the photographer behind one of the most influential images ever (shown below), is Dorothea Lange. If you’ve ever seen photos from the Great Depression, you’ve seen some of her work. Her photos shaped the field of documentary photography and showed the camera’s potential as a storytelling and reportage tool.

- Quote: “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.”

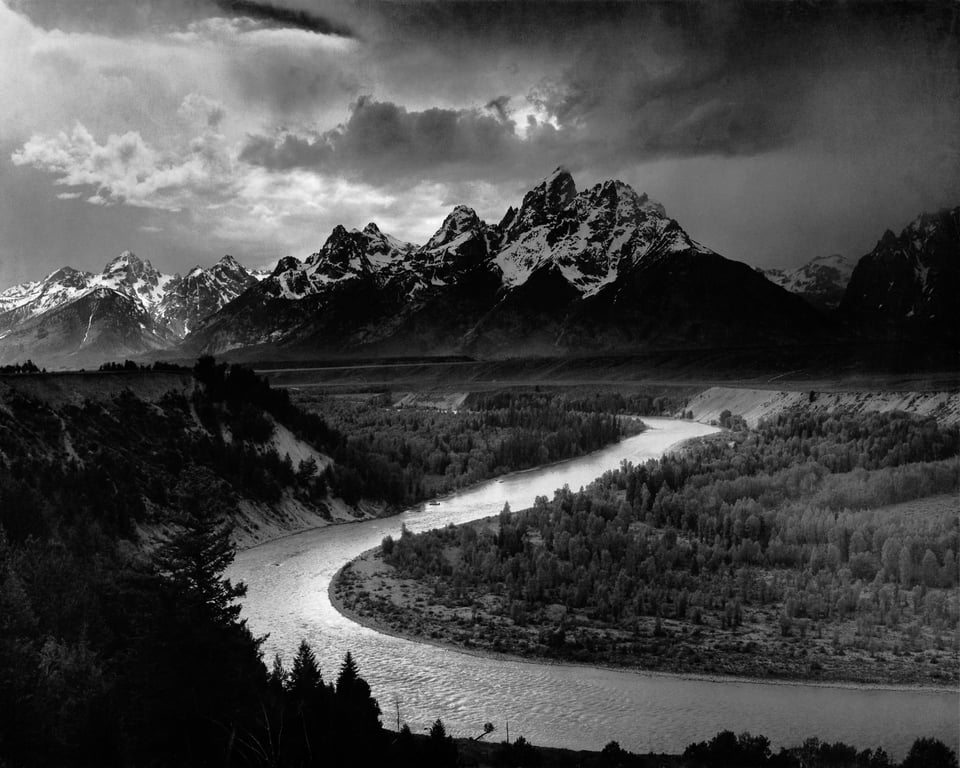

5. Ansel Adams

- Genre: Landscape photography

- Where: United States

- When: 1920s to 1960s (for most of his work)

- Impact: Ansel Adams is perhaps the most famous photographer of all time, which is remarkable because he mainly took pictures of landscapes and natural scenes. (Most famous photographers have tended to photograph people instead.) Ansel Adams helped usher in an era of realism in landscape photography, and he was an early champion of the environmentalism and preservation movements in the United States.

- Quote: “There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.”

Of course, there have been countless influential photographers throughout history, but these five are some of the most uniquely important to know. Photography didn’t arise out of a vacuum; it was willed into existence by the work of many people. And it thrives today as an art form because some of us continue to be curious about the mysteries of photography, even at a time when almost everyone carries a camera in their pocket.

Do You Need a Fancy Camera?

Apple became the world’s first trillion dollar company in 2018 largely because of the iPhone – and what it replaced.

Alarm clocks. Flashlights. Calculators. MP3 players. Landline phones. GPSs. Audio recorders.

Cameras.

Many people today believe that their phone is good enough for most photography, and they have no need to buy a separate camera. And you know what? They’re not wrong. For most people out there, a dedicated camera is overkill.

Phones are better than dedicated cameras for most people’s needs. They’re quicker and easier to use, not to mention how easy they make it to share photos quickly. Getting a dedicated camera only makes sense if your phone isn’t good enough for the photos you want (like photographing sports or low-light environments) or if you’re specifically interested in photography as a hobby.

That advice may sound crazy coming from a photographer, but it’s true. If you have any camera at all, especially a cell phone camera, you have what you need for photography. And if you have a more advanced camera, like a DSLR or mirrorless camera, what more is there to say? Your tools are up to the challenge. All that’s left is to learn how to use them.

What Is the Bare Minimum Gear Needed for Photography?

Camera. If you buy a dedicated camera (rather than a phone), pick one with interchangeable lenses so that you can try out different types of photography more easily. Read reviews, but don’t obsess over them, because everything available today is pretty much equally good as its competition. Find a nice deal and move on.

Lenses. This is where it counts. For everyday photography, start with a standard zoom lens like a 24-70mm or 18-55mm. For portrait photography, pick a prime lens (one that doesn’t zoom) at 35mm, 50mm, or 85mm. For sports, go with a telephoto lens of at least 200mm and ideally 300mm or longer. For macro photography, get a dedicated macro lens. And so on. Lenses matter more than any other piece of equipment because they determine what photos you can take in the first place. (For what it’s worth, the “millimeter” number in a lens’s name refers to how far zoomed in it is. Only point-and-shoot cameras measure zoom in numbers like 8x, 20x, or 30x. Professional lenses list the millimeters instead. The higher the number, the stronger the telephoto.)

Post-processing software. One way or another, you need to edit your photos. The software that comes with your computer probably won’t cut it in the long run. I’m not really a pro-Adobe person, but at the end of the day, Photoshop and Lightroom are the industry standards for photo editing. An open-source Lightroom alternative called Darktable is a very good option if you’re on a budget. Whatever you pick, stick with it for a while, and you’ll learn it really well.

There are other things that might be optional, but can be very helpful:

- A tripod. A landscape photographer’s best friend. See our comprehensive tripod article.

- Bags. Get a shoulder bag for street photography, a rolling bag for studio photography, a technical hiking backpack for landscape photography, and so on.

- Memory cards. Well, these aren’t optional. Choose something in the 64-128 GB range to start. Get a fast card (measured in MB/second) if you want to shoot fast bursts of photos, since your camera’s memory will clear faster.

- Extra batteries. Get at least one spare battery to start, preferably two. Off-brand batteries are usually cheaper, although they may not last as long or maintain compatibility with future cameras.

- Polarizing filter. This is a big one, especially for landscape photographers. Don’t get a cheap polarizer, or it will harm your image quality. The one that I use and recommend is the B+W high transmission nano filter (of the same thread size as your lens). See our polarizing filter article for more info.

- Flash. Flashes can be expensive, and you might need to buy a separate transmitter and receiver if you want to use your flash off-camera. But for genres like portrait photography or macro photography, they’re indispensable. (Linked here is one of the cheaper high-quality flashes I recommend, and the associated trigger to use it off-camera.)

- Better computer monitor. It’s almost essential to get IPS monitor (like this relatively inexpensive one) for editing photos, rather than a TN-panel monitor. If you don’t know what that means, we have an article about the difference. I also recommend a color calibration device so you know you’re editing accurate colors. Here’s the one I use if you care, but there are a million options.

- Cleaning kit. The top item is a microfiber cloth to keep the front of your lens clean. Also get a rocket blower to remove dust from your camera sensor easily and safely.

- Other equipment. There are countless photography accessories available, from remote shutter releases to GPS attachments, printers, and more. Don’t worry about these yet; you’ll realize over time if you need any of them. Instead, go out and start taking pictures first!

The Three Fundamental Camera Settings You Should Know

Once you get a camera, you’ll find that it has dozens of buttons and menu options, if not hundreds. How do you make sense of all these options? And how do you do it quickly in the field?

It’s not easy, but it’s also not as bad you might think. In fact, most of the menu options only need to be changed once, and then you’ll rarely or never touch them again. Only a handful of settings need to be changed frequently. (And those are what the remaining chapters of this Photography Basics guide covers, so you’re in good hands!)

The three most important settings are called shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. All three of them control the brightness of your photo – an invaluable concept – although they do so in different ways. In other words, each brings its own “side effects” to an image. It’s a bit of an art to know exactly how to balance all three for a given photo, but once you know, you can deliberately set them in such a way to achieve the “side effects” that look best for your particular photo.

- Shutter speed: The amount of time your camera sensor is exposed to the outside world while taking a picture. Chapter 3: Shutter Speed

- Aperture: Represents a “pupil” in your lens that can open and close to let in different amounts of light. Chapter 4: Aperture

- ISO: Technically more complex at a physical level, but you can think of it as being similar to the sensitivity of film. More sensitive film = better in low light. Raising your ISO is also similar to brightening a photo in post-processing. Chapter 5: ISO

Settings: Shutter speed of 20 seconds, aperture of f/2, and ISO of 1600

The First Steps on Your Photographic Journey

In photography, the technical and the creative go hand in hand. In a way, every choice of camera settings is really an artistic choice in disguise. Your understanding of photography – and your room for artistic expression – will improve tenfold when you understand how your camera works.

So, the next few chapters of this guide will cover the most important camera settings: shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. Then, we’ll dive into the deep end of composition. This is how photos are made!

- Photography Basics Introduction

- What is Photography? (You are here)

- Shutter Speed

- Aperture

- ISO

- Composition

- Metering

- Camera Modes

- Focusing

- Flash

- How to Take Sharp Pictures

- Photography Tips for Beginners

Download as an eBook

I’ve received many requests over the years to download Photography Basics for offline viewing. As of 2025, I’m excited to announce that I now have a dedicated eBook version of Photography Basics! The eBook covers the same information but is optimized for offline reading/printing, with a beautiful design and updated text. Photography Life members get this eBook included with their membership ($5/month, cancellable any time) alongside a lot of other benefits – including a Q&A group if you have questions about the topics I’ve covered in these articles. You can read more information about our memberships here.