Every advanced and professional photographer today needs to learn how to use exposure in photography. By understanding how to expose an image properly, you will be able to capture photographs of the ideal brightness, including high levels of detail in both the shadows and highlight areas. You’ll also be able to maximize a photo’s image quality. This article explains exposure in detail, as well as helping you understand the three most important camera settings: shutter speed, aperture, and ISO.

1/800 second, f/2.8, ISO 800.

Table of Contents

What Is Exposure in Photography?

In photography, exposure is the amount of light that reaches your camera sensor or film. It is a crucial part of how bright or dark your pictures appear.

There are only two camera settings that affect how much light you capture (apart from your flash): shutter speed and aperture. The third setting, your ISO, doesn’t technically change how much light you capture, but it still affects the brightness of your photos. It is equally important to understand. Also, you can brighten or darken a photo by editing it in software on your computer, or by changing the amount of light in the scene in front of you.

It sounds basic, but exposure is a topic which confuses even advanced photographers. The reason is simple: For every scene, a wide range of shutter speed, aperture, and ISO settings will result in a photo of the proper brightness. You haven’t “mastered exposure” once you can take a photo that’s the right brightness. Even your camera’s Auto mode will do that most of the time. Instead, getting the proper exposure for a photo is about balancing those three settings so the rest of the photo looks good, from depth of field to sharpness.

Finally, if you really want to master exposure, reading about it isn’t enough. You also need to go out into the field and practice what you’ve learned. There’s no quick-and-dirty way to pick up a skill like this. But if you can lay a solid groundwork, you’ll be at a huge advantage when you go out and practice it for yourself. The goal of this comprehensive article is to teach you all the basics that you need to know about exposure.

Shutter speed

We’ll start with shutter speed, which is highly important yet relatively easy to understand. Shutter speed is just the amount of time your camera spends taking a picture. This could be 1/100th of a second, 1/10th of a second, three seconds, five minutes, or anything else. Some people build custom cameras that take decades to capture a single photo.

Your camera won’t let you take a decades-long photo. Instead, the longest allowable shutter speed tends to be around 30 seconds, although it does depend upon your camera. For example, on the Nikon D850, you can shoot any shutter speed from 1/8000 second to 30 seconds, and there’s also a timer mode for even longer exposures. Other cameras generally allow similar settings.

So, why does shutter speed really matter? There are two main reasons:

First, as you would expect, a long shutter speed (several seconds) lets in a large amount of light. If you take a normal daytime photo with a 30-second shutter speed, you will capture an image that is completely white. The opposite is true, too; a quick shutter speed only lets in a small amount of light. If you take a photo at night with a 1/8000-second shutter speed, the photo will be completely black.

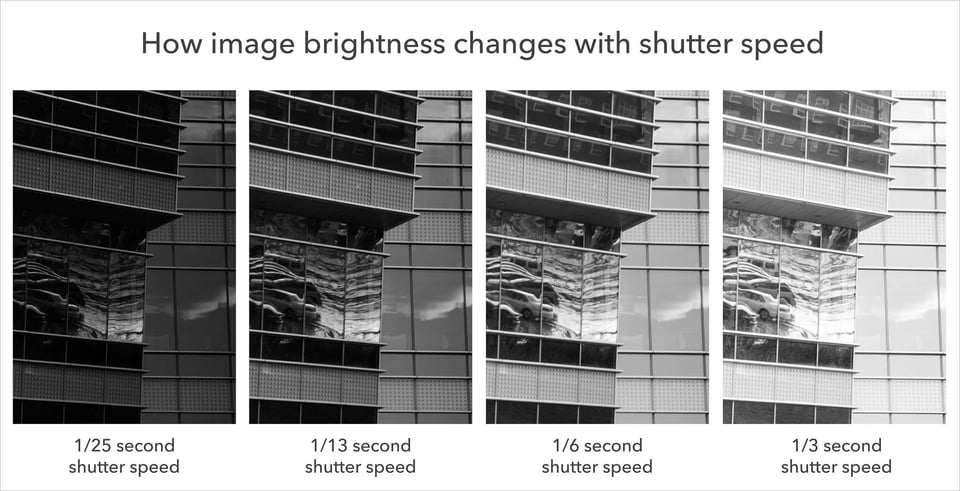

Take a look at the series of examples below. Here, 1/25 second was too dark (“underexposed”), and 1/3 second was too bright (“overexposed”). This should give you an idea of the brightness differences with shutter speed:

Second, the other big effect of shutter speed is the motion blur in your images. Not surprisingly, a long shutter speed (such as five seconds) captures anything that moves during the exposure. If a person walks by, they might appear as a featureless streak across the image, since they aren’t in one place long enough for the long exposure to capture them sharply. That’s called motion blur.

By comparison, a quick shutter speed (such as 1/1000 second) does a much better job freezing motion in your photo — even something moving quickly. You can photograph a waterfall at 1/1000 second and see individual droplets frozen in midair. Without a camera, they might have been invisible.

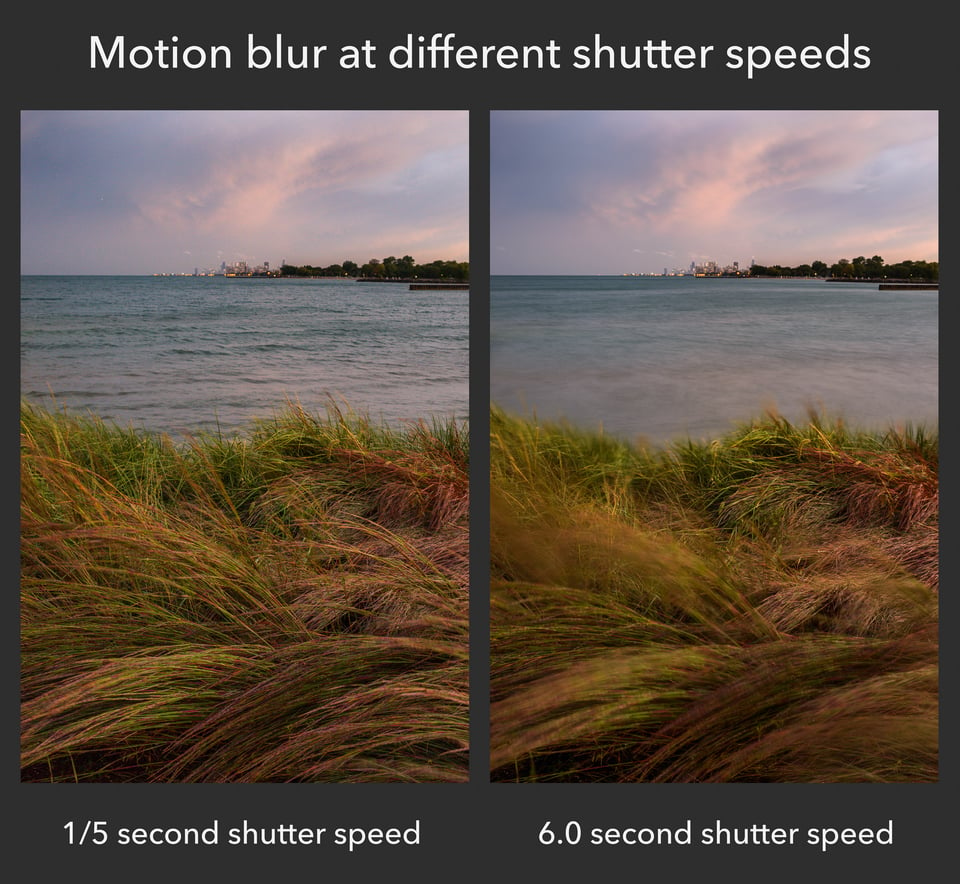

Take a look at the images below. Here, I was taking pictures on a windy day. The foreground grass and the waves behind them were all moving quickly. As you can see, depending upon my shutter speed, there was a major difference in motion blur:

There are two types of motion blur that you may encounter due to your shutter speed: camera blur and subject blur.

If you’re doing handheld photography, camera blur could be very significant. It’s impossible to hold your camera perfectly still while you’re taking a picture, and even slight shake can lead to very blurry photos. That’s one reason why many photographers end up using tripods! (There are other benefits of tripods, too.)

However, although a tripod protects against camera movement, it does nothing to prevent scene movement. For example, if you’re taking landscape photos on a windy day – even with a tripod – you might end up with areas of blurriness, as in the image above. This is called subject blur.

Sometimes, you can use camera or subject blur artistically, and it looks good. For example, if you’re photographing clouds as they pass through a valley, a long shutter speed might be a nice touch:

However, in many cases, you probably will want to eliminate motion blur so that your entire photo is sharp. If that’s your goal, you need to pick a shutter speed that is quick enough to freeze any movement. So, what shutter speed should you use? Is there a good range that tends to provide sharp photos of moving subject?

Not really, because it all depends upon some outside factors – most importantly, the amount of movement in your scene. If your subject is moving very quickly, you’ll need a fast shutter speed. If your subject is standing still, or only moving very slowly, you can get away with a longer shutter speed.

Also, the farther you zoom in (i.e., the longer your “focal length”), the more you’ll magnify motion blur. So, you’ll find that you generally need quicker shutter speeds to freeze motion properly when you’re using something like a telephoto lens.

The best route to learn all of this is just to keep practicing. Over time, you’ll build a good mental picture of the shutter speeds you can use in a particular environment without risking motion blur. Whether that’s 1/250 second, 1/10 second, or 20 seconds, it’ll be second nature. Also, after you’ve taken a picture in the field, review it and see if there is any blur when you zoom in. If so, you’ll need a quicker shutter speed.

Want a quick-and-dirty guideline? Use 1/500 second or faster for sports and wildlife action. Use 1/100 second or faster for telephoto portrait images. Use 1/50 second or faster for wider-angle portrait or travel photos where your subject isn’t moving too much. If your subject is completely still, and you have a tripod, use any shutter speed you want.

These are very general suggestions, but they are a good place to start. However, your goal should be to outgrow these tips and develop your own mental model instead. Shutter speed is one of the most intuitive aspects of exposure, and a bit of practice will be enough to help your photographs improve significantly.

Aperture

Aperture is very similar to the “pupil” of your camera lens. Just like the pupil in your eye, it can open or shrink to change the amount of light that passes through. This is how the aperture blades look on a typical lens:

Your lens probably looks something like this. The shape in the middle is called the aperture. It is made up of several blades – nine of them in this case, but your lens may differ.

Aperture blades work a lot like the pupil in your eyes. At night, your pupils dilate so you can see things more easily. The same is true for aperture. When it is dark, you can open the aperture blades in your lens and let in more light. Aperture is written as f/Number. For example, you can have an aperture of f/2, or f/8, or f/16, and so on.

It is very important to remember that aperture is a fraction. This is the biggest mistake beginners make when they talk about aperture. If you get this wrong, it will be difficult to remember how aperture works or use it yourself to capture the right exposure in the field.

Understanding aperture:

Which aperture is larger – f/2 or f/16?

Because aperture is a fraction, all you need to do is remember some elementary math. 1/2 is bigger than 1/16, which means that f/2 is the larger aperture.

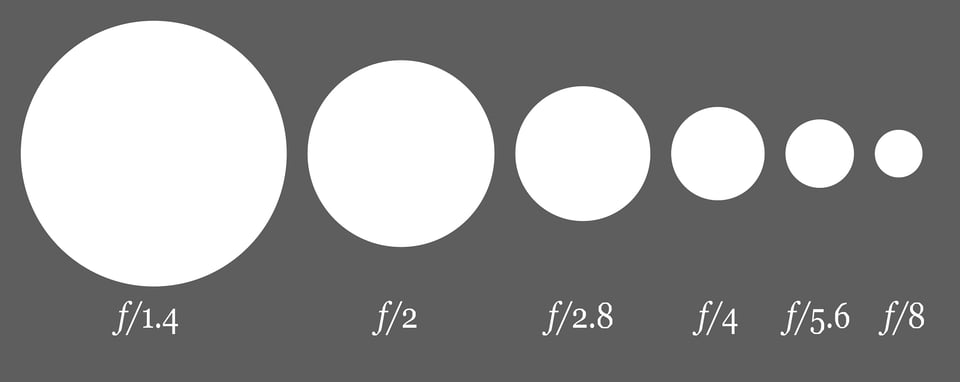

Typically, the largest aperture you can set will be something like f/1.4, f/1.8, f/2, f/2.8, f/3.5, f/4, or f/5.6. It changes from lens to lens. The smallest aperture on most lenses is something like f/16, f/22, or f/32. This diagram demonstrates the relative sizes of various aperture settings:

So, which aperture setting is best for photography and capturing the proper in-camera exposure? It depends upon the photo. Aperture influences many parts of an image, but it has two effects that are more important than anything else: exposure and depth of field.

Aperture and Exposure

The larger your aperture, the brighter your photo – the more light you capture. Again, your pupils work just like this, too; they open or close to let in different amounts of light. So, when you are trying to expose a photo properly, it is crucial to pay attention to your aperture setting.

A large aperture lets in more light. Apertures like f/1.4 and f/2 practically let you see in the dark. On the flip side, a small aperture like f/16 (with nearly closed aperture blades) lets in far less light. If you try to photograph Milky Way at f/16, your final image will be essentially black.

By changing your aperture and shutter speed settings, you can capture exactly the amount of light you want – resulting in a photo with the proper exposure. That is what makes aperture so powerful.

Aperture and Depth of Field

The other important effect of aperture is on depth of field.

Depth of field is the amount of your scene, from front to back, that appears sharp. In a landscape photo, your depth of field might be huge, stretching from the foreground to the horizon. In a portrait photo, your depth of field might be so thin that only your subject’s eyes are sharp.

Aperture changes your depth of field, which makes a big difference if you want to capture the best possible photographs. Changing the depth of field in an image will alter the way it looks completely.

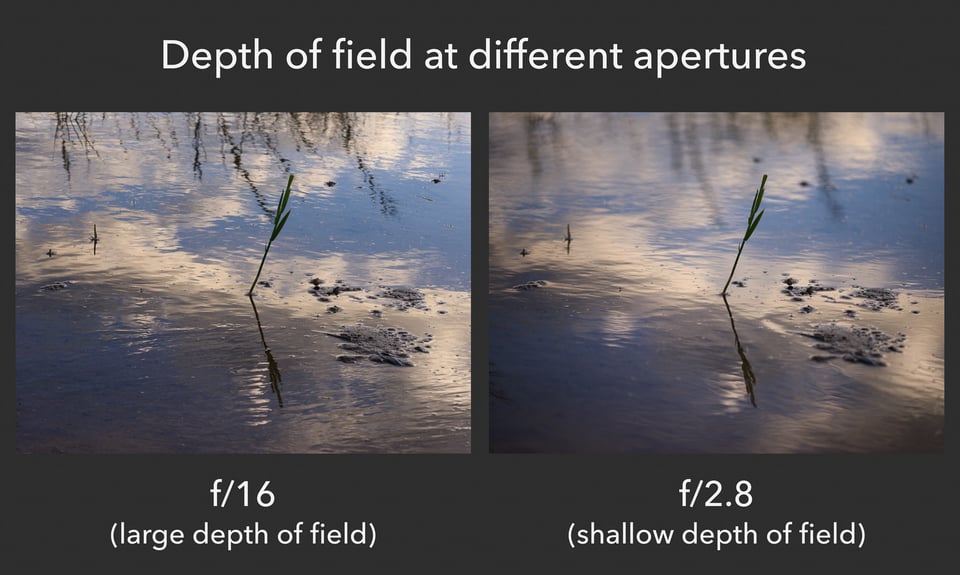

To be specific, small apertures (like f/11 or f/16) give you a large depth of field. If you want everything from front to back to appear sharp, those are good settings to use. Large apertures (like f/1.4 or f/2.8) capture a much thinner depth of field, with a shallow focus effect. They are ideal if you are trying to isolate just a small part of your subject, making everything else blurred.

Here is a sample comparison:

As you can see, that is a significant difference. The photograph on the left has a larger depth of field, which means that more of the scene appears sharp from front to back. However, the f/2.8 photo on the right has a pleasant shallow focus effect. In this case, it is arguably the better image. You will save yourself a lot of difficulties if you simply memorize this relationship.

In practice, the effects are quite clear. As your aperture gets smaller and smaller, your exposure will grow darker and darker, and your depth of field will increase. (Remember, too, that you can expose the photo back to normal by using a longer shutter speed.) The more photos you take, the less you will have to think about these effects. They will become second nature.

The Aperture Scale

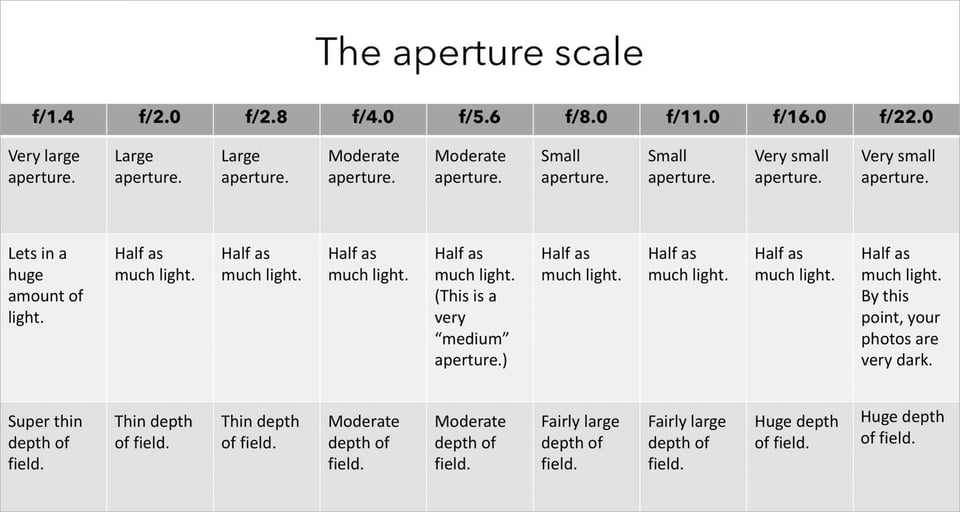

The shutter speed scale is easy to remember. An exposure of 1/100 second lets in twice as much light as an exposure of 1/200 second, because it is twice as long. Unfortunately, aperture is not as intuitive. This is the scale it follows instead:

From f/1.4 to f/2.0 (or any other one-stop jump) you will capture half as much light. You also will increase your depth of field. Also, keep in mind that you might be able to set values beyond this chart, like f/32, as well as apertures between these stops, like f/6.3, depending upon your lens.

Typically, the sharpest apertures will be somewhere in the middle of the range. On most lenses, f/4, f/5.6, and f/8 are three of the sharpest apertures. However, this varies from lens to lens. In addition, sharpness should not be your main concern. It is better to have a photo with the proper depth of field, even if it means that some low-level pixels have a bit less detail.

If you want to learn more about this topic, take a look at Photography Life’s detailed articles about aperture and f-stop. Along with that, we have another article that explains every single effect of aperture, although it is a bit advanced, and it assumes you have a decent foundation already.

ISO – Not Part of Exposure

ISO is an interesting one. It brightens your photos, but it is not part of your “luminous exposure,” since it does not affect the amount of light that reaches your camera sensor (the definition of exposure). Instead, it merely brightens a photo in-camera after your sensor has already been exposed to the light.

It is useful to raise your ISO when you have no other way to brighten your photo – for example, when using a longer shutter speed will add too much motion blur, and you are already at your widest aperture. It is a very valuable setting to have, but it is not all good news. When you raise your ISO, your photos will be brighter, but you’ll also emphasize grain (otherwise known as noise) and discolored pixels in the images along the way.

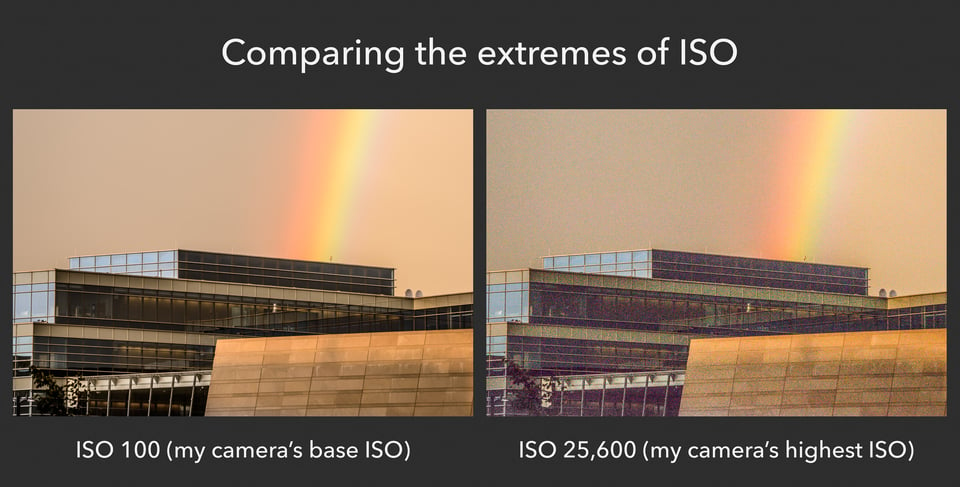

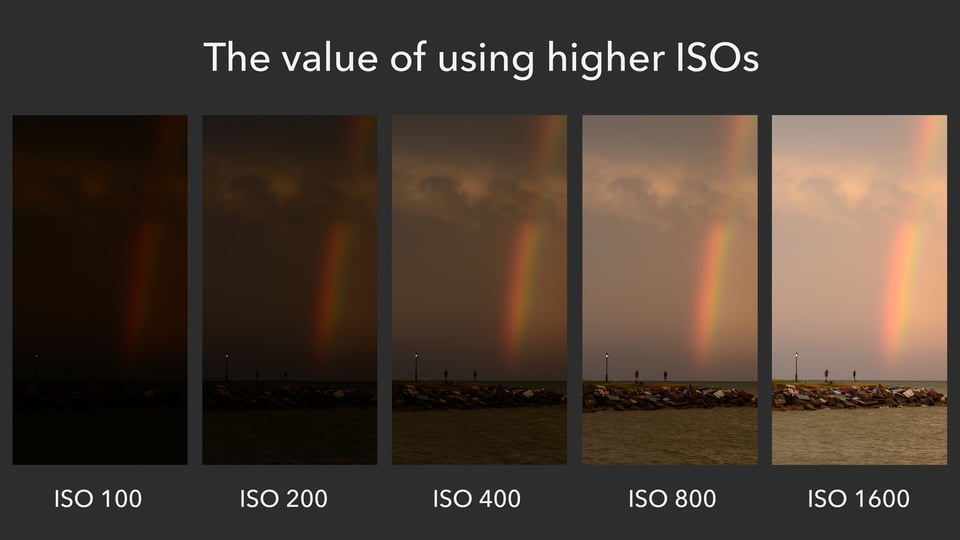

Take a look at the comparison below:

Here, the photo on the right looks way noisier, and it has some strange color shifts in the shadows. That is because it was taken at ISO 25,600, which is an extremely high ISO (more than what most photographers will ever set for normal conditions).

Still, a higher ISO will be necessary when your exposure is too dim and you have no other way to capture a bright enough photograph. In cases like that, raising your ISO is a very valuable technique to understand.

The ISO scale is easy to remember. At higher numbers, your photos will be brighter, but you also will see more and more noise. The main stops on the ISO scale are 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, and 6400. Some cameras go beyond this range, in either direction, such as the ISO 25,600 image above. Also, you can set intermediate ISO values at 1/3 or 1/2 stops, such as ISO 640 or ISO 1250.

The lowest ISO on your camera is called the “base ISO.” Typically, the base ISO will be 100, but some cameras have ISO 64, ISO 200, or something else instead. This is the lowest native ISO on your camera. If you set your base ISO and expose your photo properly, you will end up with the best possible image quality and the lowest amount of visible noise.

Note:

Certain cameras have extreme “LO” values for ISO, like ISO 32 or ISO 50. Avoid using those settings, since they are simulated and can lower your image quality. The same is true for simulated “HI” ISO settings. They offer no benefit over just brightening the photo in post-processing, and they even can harm your photograph’s dynamic range (shadow and highlight detail).

Take a look at the series of images below. Here, the photo on the left is at base ISO 100, and it is far too dark. By increasing the ISO, you will see the results continue to improve. Although there is some noise at ISO 1600 if you zoom into the pixels, a noisy photo is better than a picture that is too dark to use.

You might be wondering how much noise exists in the ISO 1600 photo above, and the answer is that the overall amount is quite acceptable. Here is a crop from the ISO 1600 photo above:

That is quite manageable. At least on this camera – and they do differ – using ISO 1600 should be perfectly fine, especially because it is possible to reduce noise to a degree in post-production. However, it still is best to use your base ISO whenever possible, capturing your photo with a brighter exposure (shutter speed and aperture) instead.

Unfortunately, you have to let in a lot of light in order to capture a well-exposed photo at ISO 100. That is fine in bright conditions, or if you are photographing a nonmoving scene from a tripod (since tripods let you use longer shutter speeds). But it will not always work. That’s why ISO adjustments are so powerful, and why they have such an important effect on your exposure even if they technically are not part of it.

So, don’t be hesitant to use higher ISO values if the scene requires it. With sports or wildlife, for example, you will take pictures at higher ISOs very often. Although that isn’t ideal, it is better than missing the photo because you’re shooting everything at ISO 100.

ISO is highly technical at the sensor level, but that isn’t important to know when you’re starting out. Instead, just use it like you would expect. Keep your ISO at the base value whenever possible. But, if your exposure (shutter speed and aperture) will not result in a bright enough photo, it is time to raise the ISO. If you follow those suggestions, your photos and image quality will be as good as possible.

A Recommendation for Most Exposures

There are no universal tips for always setting the perfect exposure. Still, many beginners have no clue where to start. If that is true in your case, you will want more than just general advice about shutter speed, aperture, and ISO; you want specific starting points that help you put all this knowledge into practice more easily.

For that reason, you will find our recommended settings below for different genres of photography. Although these are very general suggestions, they should give you a good idea of where to begin if you simply want a few basic tips for capturing a good exposure:

Typical Landscape Photography (Not at Night)

- Use a tripod. You can read more here on how to use tripods and which one to get.

- Switch to aperture-priority mode, where the camera automatically sets the shutter speed, and you manually select the aperture.

- Shoot at f/8 in general, but use f/11 or f/16 instead if you need more depth of field (such as with a nearby foreground, or if you’re using a telephoto lens). This is on a full-frame camera. Use your camera’s equivalent aperture by dividing these numbers by your crop factor.

- Set the ISO to its base value.

- Let your shutter speed fall wherever it needs to be for the proper exposure.

- Watch your highlights. Don’t overexpose any of them. If necessary, use negative exposure compensation to darken the photo. Why? It is simply easier to brighten shadows in post-processing than to darken overexposed highlights.

Portrait Photography (No Flash)

- Shoot handheld, use a tripod, or use a monopod. In this case, the best option is not set in stone. Use whatever method you are most comfortable with, or pick a setup that works best for your particular photoshoot.

- Use aperture-priority mode.

- Choose an aperture that gives you a pleasing depth of field – typically, something like f/2.8 or f/1.4, but it depends upon the look you want.

- Watch your shutter speed. If you start to notice motion blur, your shutter speed is too long, and you need something quicker.

- Keep your ISO low, but don’t be afraid to raise it if your aperture and shutter speed are not letting in enough light. In darker environments, especially, you likely will need to raise your ISO so that you can use a fast enough shutter speed.

- Once again, don’t overexpose any highlights. Use negative exposure compensation if necessary.

The shutter speed in this photo is so fast simply because it was a bright day, and, at f/1.8, the photo would have been overexposed without a fast shutter speed to darken the image.

Sports and Wildlife Photography

- Shoot handheld or use a monopod. For larger lenses in wildlife, you may need to use a tripod.

- In general, use manual mode with automatic ISO.

- Pick a large aperture, such as f/2.8 or f/4, since there often won’t be enough light

- Select a fast shutter speed that will freeze any movement in your photo. 1/500 is a reasonable starting point. You’ll need 1/1000 to freeze fast-moving sports. For birds in flight, expect to use 1/1600 or faster. See this article for more details regarding bird photography.

- Use your exposure compensation as needed so that the camera can adjust your ISO value.

- Do not overexpose any highlights (except possibly for unimportant out-of-focus backgrounds, like if stadium lights are present)

- Instead of using manual mode + auto ISO, an alternative is to use aperture-priority mode with automatic ISO. This technique ensures you will not overexpose the image in very bright conditions, but it requires jumping into the Auto ISO sub-menu periodically to change your minimum shutter speed, so it can take more time in the field. You can read more about it here.

This photograph required a high ISO of 1400 in order to use a fast shutter speed, but it was worth the tradeoff. Although there is some extra noise in this image, even the dragonfly’s winds are very sharp.

Recommended Exposure Settings Roundup

These suggested settings are not universally accurate, but they should be useful for a beginner who wants a starting point for getting the proper exposure. At any rate, they certainly work better than switching to manual mode and attempting to pick the right settings before you know what anything does. (Though, that is still a good way to learn, if you aren’t taking important photos.)

A crucial point is that you will outgrow these starting points organically as you become more and more skilled at exposure in photography. The list above does not cover some rarer scenarios (such as using a large aperture for Milky Way photos), but you will realize them pretty quickly in the field. Eventually, you should add your own points to each of these lists and expand on new exposure techniques over time.

Conclusion

Exposure can seem complicated, but it is one of the most important technical topics to know if you want to take high quality photos. The best thing you can do now is go out and test the suggestions above for yourself. Play around with your exposure settings, as well as ISO. Pay attention to how they affect a photo. Most of all, keep practicing. Exposure is something you will never stop improving, and, without a doubt, it is worth the effort to learn.

If you want further reading on this important topic, take a look at our “photography basics” articles below that go into more detail about exposure and related topics:

This article really showed me how to put the triangle together more effectively. I appreciate your information.

Great fucking advice

I will love to have a private class with you

You are so blessed with tutoring

I’m from Nigeria and I can say am

Happy I come accross this lovely article

I started my photography journey two weeks back and it still look so strange reading the terms and all settings that’s needed to bring in a well detailed photograph.God bless you kindly tag me with your IG

This article is the best I’ve read. I have tried so hard to understand more about my camera’s manual settings, but most of it went over my head. And I have read many different posts. This is explained so well that everything just clicked! Thankyou and we’ll done

I’m happy to hear it, thank you!

god tier

You explained this so well, thank you!

Awesome article !! Thanks

Just one question : for the milky way photo, how does the aperture f/1.8 (to catch more light) didn’t blur the sky (because big aperture capture smaller depth of field if I’m right ) !?

High ISO and a slower shutter speed I suppose

Fantastic article. Very helpful. Thank you very much

Hi Author,

Thanks a lot for giving this useful information; it would come handy as my basic got clear now about photography!

Regards,

Sim

Great article. Really appreciate all the great information made available!