When using telephoto and macro lenses, it is often desirable to get tighter framing on a subject that is being photographed. One of the main reasons is to magnify the subject and improve its detail in order to show it best to the viewer, but another reason could be related to improved framing and composition – by focusing tightly on the subject, it is often possible to remove the visual clutter surrounding the subject, which ultimately simplifies and enhances composition.

Although photographers can often simply move closer to their subjects to get tighter framing, sometimes it is physically impossible to do that due to the nature of the subject (such as when photographing wildlife), or when action is taking place at a particular distance (such as when photographing sports activities). In such situations, a teleconverter can come into the rescue. While teleconverters can be incredibly useful, they also have a few rather serious disadvantages that can lead to increased blur and loss of sharpness. Let’s take a look at what a teleconverter is and go over its advantages and disadvantages in more detail.

First, we will define what a teleconverter is and how it can be used in photography.

Table of Contents

What is a Teleconverter?

A teleconverter, also known as an “extender”, is a magnifying secondary lens that is typically attached between a camera body and an existing (primary) compatible lens. The purpose of a teleconverter (TC) is to increase the effective focal length of the primary lens, which unfortunately comes at the cost of decreased sharpness and reduced maximum aperture (due to loss of light). The magnification effect of a teleconverter and its effect on maximum aperture depends on its multiplication factor, which varies from 1.2x all the way to 3.0x (the most common ones are typically 1.4x and 2.0x).

For example, if one uses a 300mm f/2.8 prime telephoto lens, a 2.0x teleconverter will double its focal length and decrease its maximum aperture by two full stops, which will make it a 600mm f/5.6 lens. Teleconverters also have the same effect on zoom lenses – the whole zoom range will get magnified and their maximum aperture decreased. For example, a 1.4x TC would make a 70-200mm f/2.8 into a 98-280mm f/4.0 lens.

Optical Design

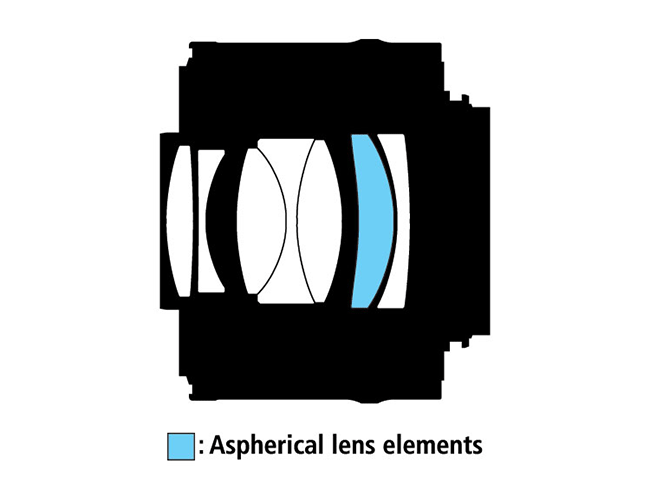

Optically, a teleconverter is typically comprised of multiple optical elements, the total number of which can vary depending on the optical design and focal length multiplication factor of the teleconverter. Typically, the larger the multiplication factor / the longer the teleconverter, the larger the physical size of the teleconverter.

Since most teleconverters are designed to be used with a number of different lenses, their optical design normally incorporates standard lens elements without optical corrections, which unfortunately results in increased optical aberrations, such as lateral chromatic aberration. However, in some cases, manufacturers try to minimize the effect of optical aberrations by incorporating more complex lens elements, such as aspherical elements, into their teleconverter design.

The use of extra-low dispersion lens elements is also rather limited in teleconverters, partly due to potential incompatibility issues with the primary lenses. There are exceptions to this too though – sometimes manufacturers make teleconverters specifically for one lens and in such cases, they can incorporate any suitable optical lens elements as part of the telephoto group of lenses.

One such known case is the NIKKOR AF-S TC800-1.25E ED, which was not only made for the exotic Nikon 800mm f/5.6E FL ED VR but also each manufactured teleconverter was tuned to specifically work only with the 800mm lens it was shipped with. Because of this, the TC800-1.25E ED teleconverter cannot be purchased separately, like all other normal teleconverters.

As a result, keep in mind that standard teleconverters designed to work with more than one lens are always going to be built with some compromises.

Common Teleconverters

Although practically every lens manufacturer involved in making super-telephoto lenses also makes teleconverters, the most common ones you will find on the market are typically limited to 1.4x and 2.0x multiplication factors. Some manufacturers, however, also produce more uncommon teleconverters with other multiplication factors, but their use and effectiveness can vary greatly by the lens.

For example, Nikon and Hasselblad make 1.7x teleconverters, while accessory manufacturers like Kenko can make teleconverters with a much larger 3.0x multiplication factor. Unfortunately, as explained below, teleconverters have rather drastic effects on lens performance both in terms of overall sharpness and autofocus speed, so one has to be very careful when choosing anything longer than 1.4x. In some cases, it might be better to crop an image in post-processing software to get closer to the subject, than to try to do the same with a teleconverter (this can be especially true when attempting to stack multiple teleconverters).

How to Mount and Use a Teleconverter

Mounting a teleconverter is quite easy – one end attaches to the camera, and the other on the lens. The male side that looks like a normal end of the lens with CPU contacts is mounted to the camera, while the female end receives the lens. You can only mount it this way.

A teleconverter is typically attached to the camera first, then the lens is attached to the end of the teleconverter. But if you prefer to attach the teleconverter to the lens first, then mount the two on the camera, that’s also an option.

Different manufacturers provide different markings on their teleconverters to make it easy to attach it to a camera or lens. Nikon, for example, has either a white line or a round dot on both sides of its teleconverters, as illustrated in some of the product images of this article.

To detach a teleconverter, just reverse the process. It doesn’t matter if you detach the lens and then the teleconverter, or you unmount both from the camera and detach them individually.

Using a teleconverter does not require any specific knowledge. If the coupling is successful, your camera should recognize the lens and behave similarly as when a regular lens is used. You will notice a decrease in maximum aperture, as well as the angle of view. Most cameras should automatically recognize the attached teleconverter and apply multiplication to the focal length automatically, so the metadata should be reflected accurately in EXIF data.

Teleconverter Lens Compatibility

As mentioned above, while teleconverters are typically made to work with more than one lens, there are no teleconverters on the market that work with every lens. Both Nikon and Canon have rather small lists of lenses (compared to the overall lens line) that are compatible with their teleconverters for a reason – most lenses are not designed to couple with teleconverters.

Some have physical limitations, such as a rear element extending too close to the camera mount, while others have optical limitations. Since most teleconverters are specifically designed for professional super-telephoto lenses, most wide-angle, standard, and telephoto lenses are not compatible with them. However, there are exceptions – some macro lenses, such as the Nikon 105mm f/2.8G VR, do work quite well with Nikon teleconverters.

In addition, it is important to point out that with very few exceptions, teleconverters made by one manufacturer are only designed to work with lenses from the same manufacturer, even if the camera mount is the same.

Below is the list of links to lens manufacturer websites, which detail teleconverter compatibility with specific lenses:

- Nikon Teleconverter Lens Compatibility

- Canon Teleconverter Lens Compatibility

- Sigma Teleconverter Lens Compatibility

- Kenko Teleconverter Lens Compatibility

Always make sure to check that the teleconverter you are planning to use is compatible with the existing lens you are planning to use it on.

Coupling Teleconverters with Prime vs Zoom Lenses

Generally, teleconverters work much better with super-telephoto prime lenses than with zoom lenses. There are several reasons for that. First, aside from very few exceptions, zoom lenses are typically slower than prime lenses, which means that they already receive less light for the camera’s autofocus system to work with. As a result, there might be a great impact on both overall autofocus speed and accuracy. In some cases, teleconverters can significantly reduce the maximum aperture of a lens, potentially completely disabling autofocus capabilities of the camera, as explained below.

Second, it is very hard to optimize a zoom lens to perform evenly at all focal lengths by the manufacturer, which makes sharpness uneven and inconsistent across the zoom range when a teleconverter is added.

Third, with more lens elements moving in groups when zooming, lens decentering and other optical problems become even more apparent.

However, there are cases when teleconverters do work well with zoom lenses. For example, the Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8G VR II is known to work well with the TC-14E II/III, very well with the TC-17E II and if one is willing to stop down to the f/8 range, even the TC-20E III can be quite a usable combination.

The Pros and Cons of Using Teleconverters

The obvious advantage of using teleconverters is extended reach at a relatively low cost. This becomes especially true when utilizing high-quality prime lenses with a variety of teleconverters.

Focal Length Versatility

For example, the Nikon 300mm f/2.8G VR II is a phenomenal lens that works well with all three modern Nikon teleconverters, TC-14E III (1.4x), TC-17E II (1.7x) and TC-20E III (2.0x). With these teleconverters, the 300mm f/2.8G can transform into 420mm f/4, 510mm f/4.8, and 600mm f/5.6 lenses, which makes it a very versatile option for sports and wildlife photography. The 1.4x and 1.7x teleconverters have little impact on autofocus performance and sharpness because the lens was specifically optimized in its design to couple well with these teleconverters.

The 2.0x teleconverter certainly does degrade AF performance and especially sharpness, but stopping down the lens by a full stop still makes it quite a usable setup. In essence, this allows the 300mm lens to cover three additional focal lengths from 420mm all the way to 600mm!

No Change in Minimum Focus Distance

Another advantage of teleconverters is that they do not affect the minimum focus distance of a lens. Teleconverters do not affect the optical characteristics of lenses – they only magnify the center portion of the frame. This means that if one were to use a telephoto lens with a short minimum focus distance, it could be used as an excellent option for extreme close-up / macro photography as well.

For example, the Nikon 300mm f/4E PF ED has an impressive minimum focus distance of 1.4 meters. The 1.7x teleconverter would extend its reach significantly all the way to 510mm. At such close focusing distance, the lens will have its reproduction ratio increased by the same multiplication factor of the teleconverter lens, so it will go from 0.24x to 0.41x with the 1.7x teleconverter. A nice option for occasional macro work for sure!

Similarly, when macro lenses are coupled with teleconverters, their reproduction ratio gets increased as well, allowing for even closer than 1:1 magnification. However, if one desires to decrease the minimum focus distance of a lens, it is only possible to achieve that with the help of extensions tubes, close-up lenses, and lens reversal tricks.

Image Degradation with Teleconverters

As you can already tell, some teleconverters have serious disadvantages that you have to keep in mind. Aside from lens compatibility and cross-brand compatibility issues, teleconverters decrease the overall sharpness of the primary lens, magnify its lens aberrations, and reduce autofocus speed and accuracy. This is especially true for 2.0x and longer teleconverters.

Increasing focal length can also magnify other variables, such as thermal distortion. That in itself can be a very frustrating issue to deal with in the field.

However, the biggest negative drawback of teleconverters is their impact on overall sharpness. Let’s take a look at the impact of teleconverters on lens sharpness and contrast, based on my detailed research.

Reduced Sharpness

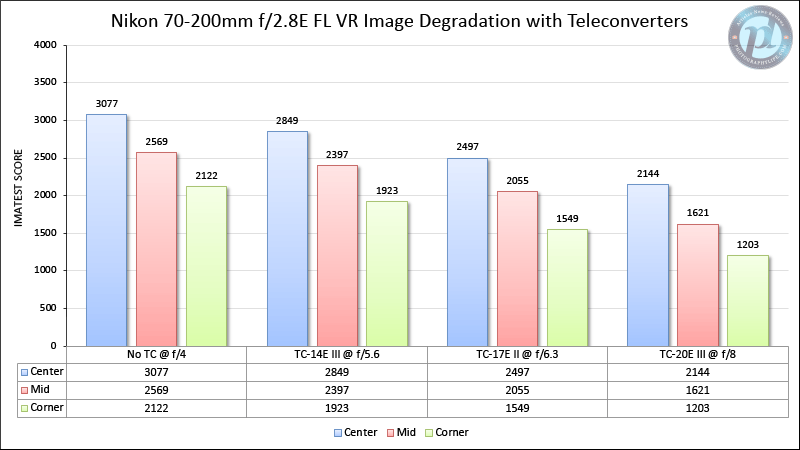

I measured the sharpness of the Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8E FL VR, with and without teleconverters using Imatest, to see how its sharpness is affected. The three teleconverters used were the Nikon TC-14E III, TC-17E II, and the TC-20E III. The Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8E FL VR was set to 70mm at f/5.6, its sharpest focal length and aperture. With the three teleconverters, the focal length change was roughly equivalent to 100mm (1.4x), 120mm (1.7x) and 140mm (2.0x). Below are the results that I was able to obtain:

For most people, these numbers don’t mean anything. I did the math to figure out the percentages and once I compiled the mean data, here is what I came up with:

- Nikon TC-14E III – 7% Sharpness Loss

- Nikon TC-17E II – 19% Sharpness Loss

- Nikon TC-20E III – 30% Sharpness Loss

Now keep in mind that this is the best-case scenario when everything is stopped down to the best aperture for the lens. I shot the TC-14E III at f/5.6, TC-17E III at f/6.3, and TC-20E III at f/8. Opening up or stopping down the lens produced inferior results.

It is important to point out that the above percentages are only for the center of the frame. If you look at the numbers, you will notice that the teleconverters impact mid-frame and corner performance differently. This is due to the fact that the extreme corners magnify lens aberrations heavily. In the case of the Nikon TC-20E III, the lens sharpness was much worse compared to the center at 43% sharpness loss.

As you may already know, the maximum aperture changes when using teleconverters. If I shot these wide open, the numbers would be totally different. All teleconverters behave differently at maximum aperture, with the TC-14E III having the least impact on the sharpness, and both TC-17E II and TC-20E III having the most (I would say both are fairly soft wide open, depending on what lens you mount them on). Also, keep in mind that this test only shows performance on one lens – TCs vary in performance on different lenses. You can expect both the TC-17E II and the TC-20E III to behave differently on fast prime lenses like 200mm f/2, 300mm f/2.8, etc.

What makes it even tougher to assess performance, is that sample variances in both teleconverters and lenses can work hand-in-hand or against each other, especially for 1.7x and longer teleconverters. That’s why some photographers might swear by a combination of one particular teleconverter and lens that works for them, while others might find results unacceptable when using the same exact setup.

In summary, when using teleconverters in the field, you could expect the 1.4x teleconverter to lose about 5-7% sharpness, 1.7x to lose 17-20% and 2.0x to lose 30% and above. The TC-14E III is a no brainer here – with its minimal sharpness loss, you won’t see any difference between the original and with the TC attached. All three will look great if you are down-sampling, but differences will be visible when doing 100% crops. For birders, this means that you might not see that same level of detail on feathers and hair that you would see when using the lens without any TCs, or with the TC-14E III attached.

Reduced Contrast

In addition to the loss of sharpness, the overall contrast of the lens is also reduced, which is especially noticeable when using 2.0x teleconverters. You will notice differences in contrast right away once images are loaded into post-processing software like Lightroom and Photoshop.

Images captured with 1.7x and 2.0x teleconverters will require more post-processing efforts to make them look good when compared to images captured without a teleconverter. As long as there is enough detail in the image, boosting contrast in post is usually not a problem.

Impact to Lens Calibration

You might also notice that teleconverters can really mess with lens calibration adjustments, resulting in front or back-focused images. This can be a very frustrating issue if your lens requires AF Micro Adjustment, because using a teleconverter can require a complete re-assessment of the combination.

Personally, I found the 1.4x teleconverter to have the least impact on lens calibration, with the 1.7x and 2.0x being the worst offenders. Others have reported more serious issues when using the 1.4x with some specific lenses, such as the Nikon 70-200mm f/4, 300mm f/4 and 200-400mm.

Keep this in mind when purchasing a teleconverter, as you might need to calibrate it with the lenses you are planning to use it with.

Reduced Autofocus Performance

As I have already explained above, teleconverters can have a drastic effect on both autofocus speed and accuracy of the primary lens and the camera, since the camera’s autofocus system has less light to work with. When using a teleconverter longer than 1.4x, quite a bit of light is lost when it is passed through the teleconverter, which can confuse the camera’s autofocus system, particularly in low-light situations. For this reason, I generally recommend against the use of 1.7x and 2.0x teleconverters on slower lenses, as such combinations can result in a very frustrating experience when shooting in the field.

Here is a quick summary of teleconverters and their impact on AF speed and accuracy:

- 1.4x Teleconverters: Minimum impact on AF speed and accuracy on most lenses.

- 1.7x Teleconverters: Impact on AF speed and accuracy depends on the primary lens. Generally, slower f/4 lenses don’t couple well with 1.7x teleconverters.

- 2.0x Teleconverters: Generally, severe impact on AF speed and accuracy on most lenses. Only select f/2.0 and f/2.8 prime lenses work well with 2.0x teleconverters, and typically only in bright light conditions.

- 3.0x Teleconverters and coupling of several teleconverters: AF functions are disabled – only used with manual focus.

Teleconverters vs Extension Tubes

Extension tubes should not be confused with teleconverters, because their use and purpose are completely different. While teleconverters are always comprised of optical lens elements for the purpose of increasing focal length, extension tubes are physical attachments without any optics, the sole purpose of which is to reduce minimum focus distance for increased magnification. Because of this, extension tubes are used for macro work, whereas teleconverters are used to get closer to action.

Teleconverter vs Cropping in Post

In some cases when using slow zoom lenses with a teleconverter, or when coupling several teleconverters together, image degradation can be so severe, that one might be better off cropping images in post-processing. In cases where autofocus functions are severely impacted and limited by a teleconverter, it is sometimes better to use a shorter teleconverter or drop the use of a teleconverter completely. What is better – a magnified out of focus subject, or a sharp subject with less resolution? That’s something you will have to assess and evaluate when using teleconverters, on a case-by-case basis.

NIKON Z7 + 300mm f/4D @ 420mm (1.4x TC), ISO 200, 10 sec, f/8.0

Personally, aside from a couple of specific combinations, I personally avoid using 2.0x teleconverters. I regularly use 1.4x and sometimes 1.7x teleconverters, but I find 2.0x to be too much of a compromise on most lenses out there due to the above-mentioned AF issues and severe loss of sharpness/contrast. Sharpness and contrast can be improved in the post, but focus problems cannot.

However, there are always exceptions to keep in mind. Some lenses work acceptably well with 2.0x teleconverters and their use and practically could even improve in the future, thanks to newer technologies. One example of this is the Sony FE 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 GM OSS, which works surprisingly well with 2.0x Sony teleconverter, even at the longest end of the zoom range.

Teleconverter vs Cropping in Camera

With many modern cameras offering shooting in crop modes (for example, most Nikon FX / full-frame cameras allow shooting in 1.5x DX crop mode), one might wonder if it makes sense to use a crop mode instead of a teleconverter to get closer to action. As we have numerously said in a number of articles at Photography Life, in-camera cropping is in no way different than cropping in post-processing, so it does not offer any additional benefits, aside from perhaps slightly increased frame rates and smaller files. If the latter two are not a concern for you, switching to a camera crop mode rarely makes sense, as you can crop images easily in post later. In fact, if a subject gets too close to the camera during shooting, you might miss your shots completely because of this in-camera cropping!

Hence, in-camera cropping will never have the same effect as the use of a teleconverter. Teleconverters effectively increase focal length, whereas cropping simply reduces the field of view.

Nikon Teleconverter Overview

Wondering about which Nikon teleconverter to pair with your lens? Over the years, I have used many different teleconverters, but the ones I used the most were Nikon-branded. Below are my thoughts on each teleconverter and its field use, based on my experience.

The Nikon TC-14E III is simply excellent. I have not seen it degrade image quality on any Nikon lenses to the level where I could see an obvious loss of contrast or sharpness. I have used it with the Nikon 105mm VR, all three versions of the Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8, 300mm f/4D and 300mm PF, and pretty much every expensive super-telephoto lens. I take it with me everywhere, and mine stays pretty much glued to my Nikon 300mm f/4D AF-S the majority of the time – that’s what I still use primarily for birding (although the newer 300mm f/4 PF is even sharper and lighter). The TC-14E III is the smallest and the lightest of the three teleconverters. Its predecessor was also quite excellent, but for compatibility reasons with modern E-type lenses, I would recommend getting the latest TC-14E III version.

The Nikon TC-17E II is a mixed bag. It works with many Nikon lenses, but it slows down AF and impacts AF accuracy. Not as good of a TC to be used with slower f/4 lenses, which includes the 300mm f/4, 200-400mm f/4, and 500mm f/4 lenses. I have used it with my 300mm f/4D AF-S and it makes the lens hunt, especially in anything but good lighting environments. The same thing with the Nikon 200-400mm f/4G VR II, although AF accuracy is not bad on newer Nikon DSLRs like D850 and D5. On fast f/2-2.8 lenses, it performs pretty well. It works great on the last two Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 lenses, and it does not disappoint with the 200mm f/2, 300mm f/2.8, and 400mm f/2.8 lenses either. The TC-17E II is quite old, and it has not been replaced by the third generation yet.

The Nikon TC-20E III is much better than its predecessor (which was very disappointing on many lenses). It performs surprisingly well on the 70-200mm f/2.8G VR II (stop down to f/8 for best results), but not so well on the newer FL version in terms of potential sharpness and AF accuracy. It works like a champ with the 300mm f/2.8 and 400mm f/2.8 lenses. On slower f/4 lenses, however, it is pretty disappointing. It is unusable on both Nikon 300mm f/4D / PF, and 200-400mm f/4 lenses, and while it will work with the 500mm f/4 and 600mm f/4 lenses, you will have to stop down to f/11 to get anything reasonably good. You will also need to use one of the latest Nikon DSLRs like D850 and D5 that focus better in low light. Not a great setup for fast action, but could work for large animals when shooting over long distances.

Sony Teleconverter Overview

While my experience with the Sony system is not as extensive as Nikon, I have previously used both Sony FE 1.4x and 2x teleconverters on a variety of Sony cameras. Below is the summary of my findings.

The Sony FE 1.4x teleconverter is very similar to other 1.4x TCs on the market in terms of its versatility. It has very little impact on image sharpness, contrast, and autofocus performance. I used the Sony FE 1.4x with a number of different lenses, including the Sony FE 70-200mm f/2.8 GM and FE 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 GM, and it performed flawlessly, as expected. Based on my experience in the field, the 1.4x is a no-brainer for anyone who wants to get closer to action when using Sony mirrorless telephoto lenses. I have not tried it with the Sony super-telephoto lenses yet, but I have heard good things about it from other wildlife photographers who use the Sony system.

The Sony FE 2.0x teleconverter is shockingly good. Being used to Nikon’s 2x teleconverters, I was expecting to see a lot of issues with the Sony 2x TC when I first tried it out. And yet when I mounted it on the Sony A9 and coupled it with the slow Sony FE 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 GM zoom, I couldn’t believe that the combination was giving me very usable results. Images were sharp and detailed, and the impact to contrast was not as noticeable as on the Nikon counterpart. Without a doubt, Sony has done a surprisingly good job with this teleconverter, something I previously thought was not technically possible. I shared my thoughts with other Sony enthusiasts and pros (some are ex-Nikon shooters), and we all seem to agree that the Sony 2x teleconverter is excellent. I would not hesitate to say that it is better than the Nikon TC-20E III.

Teleconverter FAQ

We put together a compilation of frequently asked questions related to the use of teleconverters.

A teleconverter is a magnifying lens that is attached between a camera body and an existing camera lens. The purpose of a teleconverter is to increase the focal length of the camera lens, which comes at the cost of decreased sharpness and reduced maximum aperture.

Unfortunately, no. Depending on the brand, only higher-end telephoto lenses are known to work with teleconverters. Please refer to the teleconverter compatibility list provided by the manufacturer to see if your lens is compatible with that teleconverter.

It depends on the teleconverter. With a 1.4x teleconverter, you will lose 1 stop of light, whereas a 1.7x teleconverter will result in 1.5 stops of light loss. A 2x teleconverter is the worst of the group, resulting in loss of 2 full stops of light.

2x teleconverters are quite tricky to use on lenses. Preferably, you should use a fast f/2 or f/2.8 super telephoto lens with 2x teleconverters. Due to heavy loss of light (2 stops) and image degradation due to loss of sharpness and contrast, it is recommended to stop down lenses to f/8 and smaller apertures to get acceptable results. Hand-holding lenses with 2x teleconverters can be very difficult, so a tripod and good camera shake mitigation techniques are recommended.

Based on heavy field use of all three Nikon teleconverters, the TC-14E III is currently our top recommended teleconverter. It has very little impact on image quality, and it works well with most Nikon telephoto and super-telephoto lenses.

If you use branded teleconverters from Nikon, Canon and Sony, you cannot stack them on top of each other. However, some third party manufacturers like Kenko allow stacking teleconverters. Please note that stacking teleconverters is not recommended, as that will significantly decrease image quality and result in loss of autofocus functions.

No, it does not. A teleconverter does not change the physical size of aperture of the primary lens – it only magnifies the projected image. A 300mm f/2.8 lens with a 2x teleconverter will have the same depth of field as a 600mm f/5.6 lens, at the same focusing distance.

There is no difference. Some manufacturers like Canon prefer using the term “extender”, while others like Nikon and Sony prefer using the term “teleconverter.

Yes, they do. 1.4x teleconverters affect autofocus speed and accuracy less than 1.7x teleconverters. 2x teleconverters can affect autofocus capabilities considerably, potentially resulting in loss of autofocus, especially in low-light situations. It is recommended to use modern cameras with higher AF detection range when using 1.7x and 2x teleconverters.

Yes, they do, depending on teleconverter magnification, optical design, optical quality, and other factors. Generally, 1.4x teleconverters impact image quality very little, while 1.7x, and especially 2x TCs can result in heavy loss of sharpness and contrast.

Hope this article helps our readers in understanding how teleconverters work and when one can utilize them. If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to post them in the comments section below.

It would be more clear to explain the loss of light by the loss of FOV. Less FOV means less field of incoming light therefore getting less light to make an image from that field than the original FOV before putting on the TC. FOV gets smaller weather you zoom into the original lens image circle with a TC or by simply lengthening the lens tube. It is not as if the teleconverter is throwing light away because of its materials somehow. Yes, a tiny amount is lost from the added refracting but usually nothing really significant.

In the depth of field paragraph, it is incorrect to state that 300/2.8 has the same depth of field with 600/5.6. Please use the DOF calculator / formula to check the result.

Well, that isn’t what the paragraph states.

QUOTE [clauses itemized for explicitness]

𝟷. A 300mm f/2.8 lens

𝟸. with a 2x teleconverter

𝟹. will have the same depth of field as

𝟺. a 600mm f/5.6 lens

𝟻. at the same focusing distance.

END OF QUOTE

Hello Nasim… it seems that the article originally referred to the f4 version of Nikon’s 70-200 which now appears as the f2.8 G VRII version. The correct max aperture for this lens, as well its predecessor and successor, would be f5.6 with the TC-20E III. I use both the TC-20E III and TC-14E III with Nikon’s 120-300/2.8E FL with outstanding results; I just bought the TC-17E II to try out and expect this one will deliver similar results, though I’ve read of some anecdotal concern for variation in that TC. I’ve been a follower of your column for years, thank you for your contributions to the photography realm. Cheers!

This is an 1:1 copy of your arti le:

www.pixolum.com/blog/…ekonverter

Hi Nasim,

Great article.

I am planning to purchase a 1.4 Nikon teleconverter and use it with a Nikon 70-200mm f/4 lens on an African safari. I know that 280mm is “short”for wildlife but if I were to then crop the image, where necessary, in post is that reasonable compromise? Your answer will help me to make a final decision.

Thank you and Best Regards,

Noshir

I use a similar combination (Nikon 70-200 F2.8 + 1.4x converter) on my African photo trips. It works very well for most close and medium range subjects but won’t do for birds (except maybe an ostrich or stork) or subjects further away. For that I use (and you need) a 500mm F4 or similar. Your lens is super sharp and will lose only a touch of sharpness with the 1.4x so cropping will be an option and the combination will cover the majority of what you are likely to see on a group tour. I wish you good shooting and a great trip.

Betty, thank you for your response. Much appreciated.

Noshir

I agree with an earlier comments, 70 – 200 mm F/4 while an excellent lens won’t cut it for bird photography — even with significant cropping. And that will only lose you more pixels. I moved up to the Nikon 500mm PF F/5.6 for birding and have excellent results — image quality and sharpness. My main camera is the Nikon D850. The larger sensor also provides some latitude for cropping, which is inevitable with bird photography. While I have the 1.4 extender I rarely, if ever use with the 500mm.

Regards, and good luck,

Michael

Thank you, Michael.

Regards,

Noshir

If you are going to photograph something from a far distance like sports, airplanes, whatever, and you know you will need to crop say 500 pictures when you get home, then it can be a smart idea to select DX-crop, because then the work is already done.

Not really.

Using the full frame gives you lots of leeway in composing especially if the subject is moving. Using in-camera crop limits your ability to do this with moving subjects being at risk of ‘falling off the frame’.

Cropping in post avoids this potential problem – with no downside.

Thanks for the article.

Agree about the Sony TCs.

They work very well with the FE400mm 2.8 too.

Only drawback is distinct vignetting.

Thank you for what is, by a long way, the most comprehensive and informative article I’ve seen on teleconverters. However, I think it could be even better with more reference to sensor pixel densities. I see that many of the shots illustrating the article were taken on 12 MPx cameras.

D700, D3S pixel pitch 8.42 µm, D850 4.34 µm, Sony Alpha 7Sii 8.32 µm, Sony Alpha 7Riv 3.76 µm, Canon EOS 90D 3.19 µm.

For example, one shot was taken with a Nikon D3S, 300mm lens and 1.7× TC. If the shot had been taken on a D850 using the same lens but no TC, and cropped to 15.7 MPx, that would have shown the same field of view. I assume the D850 would also have captured a little more detail, both because of the slightly higher pixel count, and through omitting any slight degradation to the optical path from inserting the TC between lens and sensor. (Alternatively, use a D5600 at 3.89 µm, costing about the same as a TC, although it wouldn’t match the handling of the D3S.) The current Sony FF range goes from 8.32 to 3.76 µm, equivalent to a 2.2× TC.

Also, I wonder whether a TC might improve the performance of a given lens on a low-MPx body, where the lens out-resolved the sensor, yet degrade performance on a high-MPx body, where the sensor out-resolved the lens.

Chris Newman

Yes, in broad terms there will be differences between DX and FX sensor pixel pitch/density and yes, in broad terms there will be small differences using a teleconverter as opposed to cropping, but at the end of the day it amounts to little or nothing when compared to to good technique, accurate autofocus and correct exposure not to mention making a pleasing image.

I guess it depends on whether one’s love affair is with the art of photography or shooting test targets in controlled conditions.

Hi Nasim, thanks again for a great piece of work. Some time ago I have read the sharness comparison article with great interest and after reading it, I decided to use only the TC-14EII. And I have to say I am quite impressed with the results I can get with the TC-14E II considering it is not the latest edition. I have got the 500f4 G and the 300f4 PF and I use both of them with this TC. In fact I have two, because I don’t have so much opportunity for shooting and it happened quite often to me that while sitting somewhere with the 500f4 G + TC on the tripod, other creatures started creaping and hopping around me that I used to miss out in the past. So, depending on the situation I have a second body on my laps witth the 300f4 PF plus or without the second TC, which gives me the 700f5.6 plus a handholdable 300f4 or 420f5.6 and it works fine.

There is only one issue: The TC’s have to be dedicated to the lens because otherwise you end up with wrong setting of the AF fine adjustment. I have got one that is purely for the 500f4 G and the other one for “the rest”.

Would you mind sharing your concerns regarding the compatibility of the TC-14E II with E type lenses, please ?

Up to now I didn’t face any issues with using my “old” converter on the 300f4 PF – which an E series lens – instead of the TC14E III, even when shooting bursts of images.

Great overall article Nasim. But what I miss entirely in the discussion is the influence of pixel size/pitch: While it may make sense to use a 2.0x with certain lenses on a low resolution camera (20-24MP) the same combination would suffer way more in relative percentages on a high resolution sensor (42-45MP), where cropping might be the better option.

For what pixel pitch are your relative sharpness degradation values calculated?