Many photographers have been buying expensive wide gamut monitors in order to take a full advantage of their ability to display over a billion of colors. What many do not realize, is that their actual workflow is most likely limited to just 16.7 million colors due to software and hardware limitations. How does one achieve a true 10 bit per channel, or 30 bit workflow? What are the advantages and is it worth the effort? To answer these questions, I decided to dig into the 30 bit photography workflow in detail and explain its advantages, disadvantages and also discuss its future.

With computer monitors advancing year after year, we are now seeing excellent wide gamut options for even those of us that are on tighter budgets. The next step in resolution is 4K monitors and we will start seeing solid, true 4K panels on the market fairly soon. With all this new technology making its way into our homes and businesses, it is crucial to understand how these new technologies can improve the results and help us get the best out of our equipment choices.

Table of Contents

1) What is a 30 Bit Photography Workflow?

If you are not a geek who understands things like bit depth, ICC profiles and other related jargon, you probably have no idea what a 30 bit photography workflow stands for. Well, don’t worry – for a while, I had no idea either! Most of us take pictures and don’t even have a clue what the “14-bit RAW” option in our camera really means! When a monitor displays an image, each displayed pixel is represented by a certain number of colors. Since the basic unit of information in computing is bits, this number is often represented as “bits”, or “bit depth” (sometimes also referred to as “color depth”). Bit depth is represented as number 2 with an exponent. For example, 2-bit color is 2² = 4 total colors. In the early days of computing, monitors used to be monochrome, which is basically 1-bit (21 = 2 colors for black and white). If you are old enough to remember EGA monitors, those used to be 4-bits with only 16 total colors. Nowadays, most screens feature 24-bit “true color” panels that are capable of producing a total of 16,777,216 colors. Because colors are made from three main colors (Red, Green and Blue), the 24-bits I am referring to represent the total number of colors, which translates to 8 bits, or 256 colors per color channel (28). So if you do the math, that’s equates to 28 x 28 x 28, or 256 x 256 x 256 = 16,777,216. So if you hear someone mention “8-bit display” today, keep in mind that they are referring to 8 bits per channel, which is a 24-bit screen with 16.7 million colors.

In comparison, a 30 bit monitor means 10 bits per channel, which is 210 = 1024. That’s 1024 colors per channel, so if we do the math 1024 x 1024 x 1024, that’s a total of 1,073,741,824 colors, which is 64 times more colors than a true color display! It would seem that a slight increase from 8 bits to 10 bits would only slightly increase the total number of colors, but as you can see, that’s certainly not the case. So if you ever wonder what you would gain by shooting a 14-bit RAW file instead of a 12-bit, we are talking about 4.4 trillion colors vs 68.7 billion, again 64 times difference in comparison! Hence, a true 30 bit monitor is significantly better in displaying more colors than a typical 24 bit monitor.

In short, a 30 bit workflow is aimed at displaying that many colors on the screen for you to see and work with. And that’s where the problem lies, because it is not as simple as it may sound!

3) 30 Bit Workflow Components

In order for you to be able to see over a billion colors in true 30 bit depth, you not only need a wide gamut monitor, but you also need other hardware and components that actually send the proper color information to the screen. First, it starts with the operating system of your computer that must be able to support outputting 30 bits. If you are a Mac user, you can stop right here, because Mac OS still has no support for 30 bit color output. As of July 2014, the latest version of Mavericks 10.9.4 is only capable of outputting 24 bits. This means that you can only attain 30 bit workflow if you are a PC user (both Windows 7 and 8 have built-in support for 30 bit output, but if you use Windows 7, you will have to turn off the Aero theme).

Second, you will need a professional graphics card such as “NVIDIA QUADRO” that has software support for 30 bit output. Although both NVIDIA and ATI video card hardware can be used for 30 bit output, NVIDIA drivers seem to be more stable for this purpose. Personally, I use an NVIDIA QUADRO K2000 video card to output to two Dell U2413 monitors (dual screen setup). Special video card drivers specifically designed for these cards will have to be installed, since 30 bit support has to be supported by both hardware and software.

Third, you will need a special cable type that can actually handle that much data output. An old DVI cable won’t work – you will either need the latest generation HDMI cable (HDMI 1.3 standard), or DisplayPort / Mini DisplayPort cables. Personally, I use DisplayPort cables – you can even daisy chain those between multiple monitors!

Fourth, you will need imaging software that can support 30 bit output. Unfortunately, this is where the biggest issue is today – aside from a small number of software packages like Adobe Photoshop CS6 / CC / CC 2014 and Zoner Photo Studio, there is no other software on the market with 30 bit support. As far as I know, Lightroom 5 still does not have 10 bit support right now and just applies dithering to make images appear smoother.

Lastly, if you will obviously need a good wide gamut monitor that can handle more than 8 bits of data. And this is where things can get tricky as well – the Dell U2413 monitor that I referenced above and personally own, for example, is not a true 10 bit monitor – it achieves 10 bits by using an 8 bit panel + FRC / dithering. True 10 bit monitors are very expensive in comparison and only a small number of companies like Eizo offer them. Sadly, this “cheating” by using dithering does not just apply to 10 bit screens – many cheaper 8 bit monitors are not true 8 bit panels either, utilizing a 6 bit panel + dithering. So don’t be too frustrated if you own an 8 bit wide gamut display, since 8 bits of native colors is still way better than 6 bits plus “emulated” colors! Also, don’t forget that your monitor must have proper digital inputs for DisplayPort, Mini DisplayPort or HDMI 1.3.

4) Adobe Photoshop 30 Bit Display Option

Once you have all of the above components and you are ready for the 30 bit workflow, you will need to make sure that your version of Photoshop is going to work. If you are not a Creative Cloud subscriber, keep in mind that CS5 had limited support for 30 bit workflow and only CS6 and above have full support for it. The initial versions of Adobe Photoshop CC had some issues with 30 bit output, but those were resolved with patches. The latest Photoshop CC 2014 has full support and works quite well.

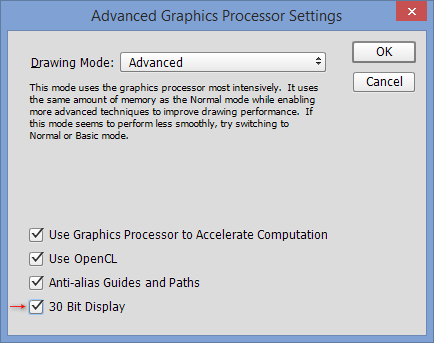

By default, Photoshop does not automatically detect and output 30 bits to your screen – you must turn that option on first! Navigate to Edit -> Preferences -> Performance, then click the “Advanced Settings” button under “Graphics Processor Settings”. You will be presented with the below window:

Make sure to put a check mark in front of “30 Bit Display” and you will be good to go!

5) How to Identify 30 Bit Output?

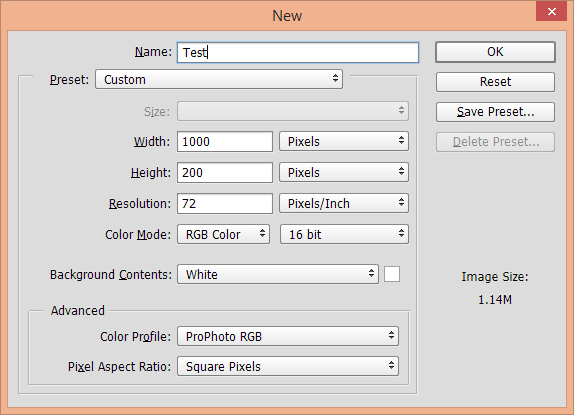

You might be wondering how to check if your monitor is actually outputting 10 bits of colors. There are two methods to find out. The first method involves creating a black and white gradient in Photoshop. First, create a new image with the below settings in Photoshop:

Once the image is open, select the Gradient Tool (G), then left-click drag your mouse from left to right (or vice versa), starting from one side of the image all the way to the other side. If you want to keep the gradient straight, hold the shift key as you do this.

With the gradient going from black to white from one side of the screen to the other, you should be able to see very smooth transitions. Take a look at the below image (make sure to open the image fully, or open it in a new window):

If you have a wide gamut display, the above image should appear smooth in your browser. And if you have a low quality display, here is what it can potentially look like:

If you see vertical lines that separate different color shades as above (also known as “banding” or “posterization”), then your screen is most likely limited to 8 bits. If you see a lot of posterization, it might not even be 8 bits…

The second test is a bit better, since it does not span so much black and white – it is mostly gray. Download this file, unzip the PSD and then open it up in Photoshop. If the whole image looks smooth, you are in 30 bit workflow. If you see those lines / posterization, then you are working in 8 bits or less.

On my properly calibrated Dell U2413 using X-Rite i1Display Pro (custom Dell drivers and hardware calibration), the file appears quite smooth with no posterization visible, which means I am getting 30 bits. Unfortunately, I cannot show you my screen as it won’t show the image properly on your monitor, but hopefully you get the idea.

6) Is it worth it?

Seeing all of the above, you might be wondering if a 30 bit workflow is worth the headache. There is definitely quite a bit of work involved in making this all work and it is not a cheap proposition by any means. If you were to ask me a year or two ago, I would definitely recommend to stay away from it. Back then, Photoshop support was quite bad and good panels were extremely expensive. However, things have changed since then for PC users for the better and now I am starting to see more people adopt a 30 bit workflow to get the best out of their images. For me, given the fact that I already own a decent IPS wide gamut monitor and the cost of getting a professional graphics card was fairly reasonable, I decided to go for it and enable the 30 bit support. While it did not make a drastic change in my workflow, I can now see more colors and I have more options for post-processing images, especially when I need to recover shadow or highlight details. Skies do not appear posterized anymore due to 8 bit limitations, which is pretty noticeable when working with landscape shots.

What about the future? Well, 30 bit workflow is far from being mainstream at the moment, but I believe that we are heading there, albeit slowly. With more people adopting high quality wide gamut monitors and increased interest in seeing more colors, I believe that more software companies will soon start offering 10 bit support. Apple has been dragging its 30 bit support for a while now and considering how widespread the use of Apple products is among the photography community, it is another big reason why adoption is very slow.

Let me know if you have any questions! We will be writing more about colors, calibration and bit depth in the next few weeks.

Thank you for this excellent article (and all the other great content on this website). You make complex topics easy to understand and very practical. I appreciate it!

I do have the hardware components for a 30 bit workflow, including monitor and an AMD FirePro graphics card. However, one of the points that struck me in your article is that you indicated Lightroom does not support 30 bit color. The article is a couple of years old. Has this changed in the mean time? I do most of my color editing in Lightroom and am now realizing that despite having the right hardware I may not be really be working in a 30 bit workflow.

Thanks again for al your great work! Very much appreciated!

Nasim, I was wondering about one thing I don’t think you mentioned. When shopping for displays, and you see the monitor is (let’s say 4K) and it’s also 10-bit (fake-10-bit) and it’s IPS… what about the 99 or 100% AdobeRGB color space? How much of an issue is that for “Photoshop” editing and work? Thanks for your work on this!

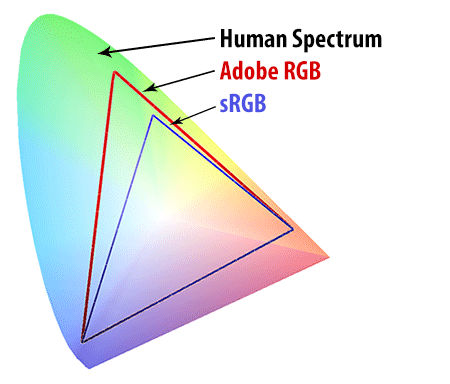

Thomas, just set the working color space in Photoshop to ProPhotoRGB. This is the largest color space available in Photoshop, and using this results in keeping most of the colors your camera sensor is able to capture (assuming you shoot RAW). Only if still available you can output them to you 99% AdobeRGB monitor. Or put the other way around: if you use sRGB, the smallest color space available in Photoshop, as yours working color space when editing your images, all colors outside of sRGB will be clipped, and if clipped, i.e. no longer in your image, you cannot display them, even if you monitor is capable of displaying 99% of AdobeRGB.

Nice introduction! Wondering how Apple is doing recently with its software and hardware, made a search then i found this post on reddit

www.reddit.com/r/app…t/dyqf9g7/

thanks for cleaning up the 10 bit confusion i had! i wonder how well apple and photoshop have come since you first wrote this!?

Hi Nasim,

thanks for your great posts here :) I just stumbled on your site while doing some research about getting a new screen for editing photos.

Unfortunately i might have found out, that i just wasted a lot money though as i ended up with a combination of things that did not make sense.

I just ordered myself a PC including a Nvidia Quadro card, after reading tons of things about how this is the card to go for for photo editing.

Awesome GPU acceleration, 10bit and whatnot.

Now i just saw that Lightroom – which i use like 95% of the time – apparently does not even support 10bit (still not, according to some entries in the Adobe forums).

Also i’m reading that here (photographylife.com/gpu-a…-lightroom) that some of the tools that would desperately need a speed up (at least from my current macbook pro), like Spot Removal, do not even use the GPU.

Right now i’m wondering if i could save a lot of money by getting rid of the Quadro again (or cancel it, if i still can).

Or would it still have other advantages that i’m overlooking right now? Unfortunately all the information i find is rater uncertain or incomplete about any real benefits, just saying “it’s a must have”.

The information on 10bit vs 8bit + frc i can find is also very sparse. Like you say in the article 8bit + frc is not “real” 10 bit, but nowhere on the internet anyone seems to have a clear answer on how big the difference is.

Until a moment ago my choice of monitor would have been a BenQ SW271 with real 10bit. But now i’m digging through reviews of 8bit + frc monitors to see how they did in calibration and color measurements, which seems to be a more realistic value, than how those colors are mapped internally.

Though it might all be pointless, if i don’t even see more than 8 bit while i’m in Lightroom… :/

Hi Benjamin,

Sorry you didn’t get a reply to your message. What did you decide regarding the video card and monitor? I am in a similar position.

I applied the gradient test (1024 * 256 px) to my gear, consisting of Asus Zenbook UX303LA sporting a Intel HD Graphics 5500 connected through DisplayPort to Eizo CS2420 display. It works! Tested eith an old €40 nVidia Quadro Fx1800 works fine too.

I’ve used your test suggestion to make a gradient in photoshop and my BenQ SW2700PT displayed a smooth gradient with no lines however the downloaded file which is an SRGB 16 Bit 72 DPI image shows banding. So which image is correctly testing the monitor? I’ve connected using the display port and the graphics card software is showing 10 bit is enabled. This monitor like your Dells is 8 bit + FRC.

Since upgrading my OS to Sierra, I have been able (to my surprise) to render the 10-bit test ramp fully smooth on a MacMini mid 2011 connected to an Eizo CS240 over either HDMI or DP. To my further surprise, it works not only in Ps, but also in the Preview application. Ps seems to correctly recognize the mediocre Intel HD Graphics 3000 and switching off the 30-bit color actually produces banding.

Hello, it’s very interesting. Can you post a screenshot with a monitor info like here petapixel.com/2015/…-mac-pros/ ?

I’m having a new computer built to be used primarily for photography. The question of whether I should have it built it to support 10-bit processing has been difficult for me to decide. I use Lightroom for photo editing and very seldom use Photoshop. I understand that Lightroom does not support the display of 10-bit color, so it seems like I would not be able to take advantage of a 10-bit capable system to achieve the more precise editing that is mentioned in the article and discussion above. This point alone seems to indicate that I should not spend the extra money to build a 10-bit system. Of course, it could be that Adobe will make a future version of Lightroom capable of displaying 10-bit color.

A second source of doubt that I have concerns what happens to the image after it is edited. This issue has been mentioned several times in the discussion thread, but not completely answered in my opinion. Let’s say that Lightroom does support the display of 10-bit color and I take advantage of the more subtle differences in color that 10-bit color provides to make precise adjustments in shadow and highlight areas of a photo. Isn’t it true that when I output the image from lightroom to a JPEG image that I will loose some of that precision and smooth gradation because the 10-bit colors will have to be “averaged” to their closest 8-bit values? If so, it seems like, for JPEG output, 10-bit processing makes no sense. However, printing may be a different story if the printer is capable of producing the more subtle differences between colors that 10-bit images provide. I don’t know if high-end desktop photo printers (e.g., Canon PIXMA 1) can do this. If anyone knows the answer to this, I’d like to know.

Arnie

You are confusing display bit depth and image bit depth.

Screen images are displayed at 6-8 bits – or 10 bits if the entire imaging pathway is correctly configured.

Image files (14 bit if uncompressed RAW) are edited at 16 bits (ideally) and are then output to screen at 8 bit or printed at either 8 bit or 16 bit (high end inkjet).

For what it’s worth:

I have a nine-year old NEC 2690 which is an 8-bit monitor though with aRGB gamut, which I profile with an X-Rite i1 Display Pro. I don’t feel at all handicapped in my print quality (including monochrome) and am often able to print straight off the soft proof. A 10-bit NEC monitor would give me greater colour and tonal depth on the screen and a 4K 10-bit NEC monitor would give me greater resolution on screen. Maybe they would lead to more accurate processing and thereby better print quality but I suspect there would be no difference for matte prints. In any case I don’t feel practically disadvantaged. Someone else is welcome to chime in and tell me what I am missing.

I understand that NEC and Eizo are in a whole different category to other monitors but I haven’t used another brand for a long time and don’t have an opinion on what might be an acceptable compromise for different budgets. I think there’s an advantage in an aRGB monitor unless you only photograph images that will fit in an sRGB gamut.

I have only recently started shooting in RAW. All of my prints so far have been from jpeg images processed using LR 4.4. I use a Nikon D7000.

I have been getting along just fine using my uncalibrated Toshiba laptop and LR 4.4 to produce very nice prints of my work. I’m sure some may opine…”Then keep doing what you’re doing”. The laptop is my only computer though, and I would like to upgrade. I will say that at this point in time, after months of research reading just about everything I can get my hands on, it appears to me that all of the incredibly in depth computer hardware/software/application/monitor discussions almost everywhere I search appear to be, in the case of simply producing quality landscape photographs, way more complex and involved than needed. It many times appears to be a case of (what we termed in the military) “measure it with a micrometer, mark it with a grease pencil, and cut it with an ax”, where all the effort in the software processing (the micrometer part) ends up not really having a measurable impact on the print hanging on the wall viewed from three or more feet away (the ax part). I will freely admit that I could be dead wrong about this, but it’s what it looks like from my end.

I will add that my objective in the field is to get the picture as close to spot-on as I can in the camera, and that I do not very often add artistic flourishes to my work through processing or subscribe to using HDR unless there is really no other way to get the shot as I see it in person. I do use LEE filters or a polarizing filter when the sensor needs some help.

I can’t say I really agree with you, even if your objective is “to avoid artistic flourishes”. And I’ve been doing this for an eternity, my eye was calibrated by years of printing Cibachrome and my partner is also an artist with a university qualification in Art and also a Fine Arts degree.

I found in my years of printing Cibachrome that it was very important to test for correct filtration when I purchased paper from a new batch. The closest you start to where you want to end up, the easiest it is to make the adjustments. In a similar way, I am confident I give myself a significant advantage through an accurate profiling of my monitor.

A jpeg is an arbitrary subset of a RAW image and the jpeg or the RAW accurately represents neither what one photographed, the exercise of imagination with which one perceived the event or object, or the different version of “reality” that seems plausible to one’s memory. Consequently, I always process an image and sometimes I will go to a considerable effort to achieve a subtle effect because often subtle effects can be very significant. Moreover, in most cases, processes that seem very complex to read about become simple when you understand them.

Similarly with printing. Sometimes I can accurately print from the soft proof of my accurately profiled monitor and sometimes I need to spend some time and effort to fine tune the print to bring out the best from the paper’s gamut and tonality. I also do my own printing because I believe I should be able to get a better result than even a custom commercial printer, being ultimately the sole repository of my artistic vision.

Regarding my prints, the finished products are generally very close to what I adjust the pictures to. And given the fact that people who see my pictures hanging on my walls throughout my house (and the people who pay me for my prints), and this I think is very important, never have a second example of any of the pictures to A/B what’s in front of them against, no one has ever questioned the colors. They just like the pictures. And that’s what counts.