Even if cell phone cameras keep improving and reach unimaginable levels of image quality, I’ll always carry around a larger, heavier, and more complex camera. Why is that? One word: lenses! An interchangeable lens camera opens up a vast world of photographic visions through a huge variety of optics. Choosing among the dozens and even hundreds of lenses can be confusing and intimidating, so in this beginner’s guide, I’ll explain the types of lenses available and what you should buy.

Table of Contents

What Does a Lens Do?

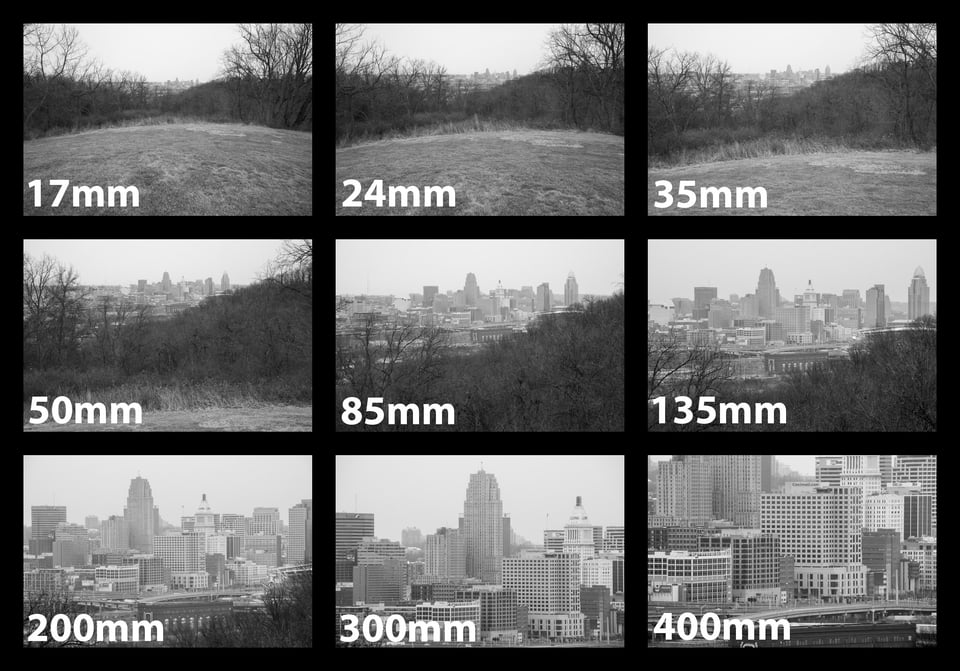

A lens focuses light to form an image on the camera’s digital sensor or film plane, much the way our eye works. And importantly, a lens determines how much of the subject is seen and captured, from the broad sweeping view of a wide angle lens to the narrow, selective view of a telephoto lens. We call this the angle of view.

Lenses are classified by their specific focal length in millimeters. At the simplest level, this millimeter marking corresponds to the distance between the lens’s optical center and the camera’s image sensor when focused. From that focal length designation, we know how an image will look – in particular, the angle of view – on a given camera. Focal length is the most important factor to determine which lens to use for a given photo.

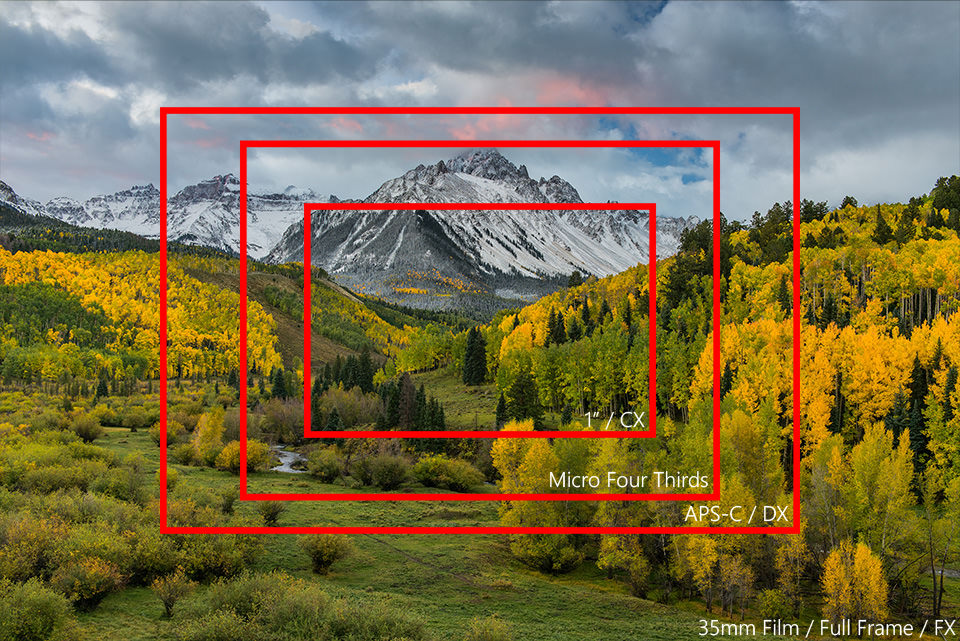

Note that the images above are taken with a full-frame camera – i.e., a camera with a sensor that’s about 24×36mm in size. If your camera has a smaller sensor like aps-c or Micro Four Thirds, it will act as a “crop” of the images above and give a more zoomed-in appearance at each focal length. To be specific, aps-c cameras have about a 1.5× crop factor, and Micro Four Thirds cameras have about a 2× crop factor. (For the remainder of this article, any time I mention specific focal lengths, I’ll be doing so in terms of a full frame camera. To get the equivalent number on your camera, it’s as easy as dividing by your crop factor.)

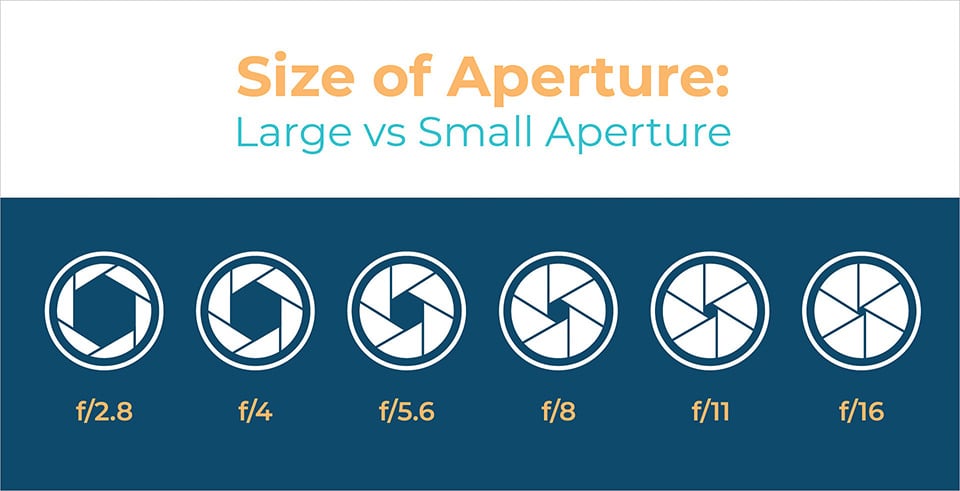

Along with focal length, a lens also has a diaphragm that can change size – commonly called aperture – which controls how much light is let through the lens (part of how we control exposure). As your aperture changes, it looks like this:

Every lens lets you change the aperture size, so you’re not stuck at one aperture. However, lenses are usually named by their maximum aperture because it’s so important – for example, the Nikon 28mm f/2.8 has a 28mm focal length and a maximum aperture of f/2.8. Other lenses have maximum apertures of f/4 or f/5.6 (which don’t let in as much light), and some go the other direction to f/1.4 or f/2 (capable of capturing much more light).

Aperture doesn’t just change how much light you capture. It also determines how much of our subject is in focus from front to back – what we call depth of field. As the aperture narrows, depth of field increases, which is why landscape photographers often use apertures like f/8, f/11, or f/16 to get sharp focus from front to back.

Combined, these two factors – focal length and aperture – are the most important features of a lens. If you know a lens’s focal length(s) and maximum aperture, you already know a great deal about what subjects it’s intended to capture. I’ll cover more about those intended subjects next.

The Normal Lens

Lenses with a “middle” focal length – not super wide, not super telephoto – are known as normal lenses or standard lenses. Many photographers swear by the normal lens as their main tool because it does not exaggerate perspective and can be pressed into service for a wide variety of photographic needs. Photos taken with a normal lens feel like looking at the world with your eyes, not a camera.

The normal lens for a given camera system has a focal length similar to the diagonal length of that camera’s sensor or film. Full-frame cameras (again, with a roughly 24×36mm sensor) have about a 43mm diagonal. The classic normal lens on full-frame is a 50mm, which is a bit longer than 43mm but pretty similar.

Normal/standard lenses were almost always sold with the camera as a kit in the film days of decades past. Today, there are still plenty of 50mm lenses available from each manufacturer (or equivalents for smaller sensors like 35mm and 24mm lenses).

Everything from family candids, low-light street scenes, wedding group photos, and even landscapes look natural with a normal lens. It’s a flexible tool.

NIKON D850 + 50mm f/1.8 @ 50mm, ISO 64, 1/4, f/14.0

Wide Angle Lens Drama

Wide angle lenses can be exciting to look through, as they take in a much more expansive view than the normal lens and can be used to exaggerate perspective in pleasing ways.

A typical use for a wide angle is in a dramatic landscape, where the wide field of view allows you to get close to an interesting foreground such as a field of wildflowers, while still capturing a sweeping view of the mountains in the background. Wide angles are also commonly used in architectural photography, such as including all of the grand interior of a cathedral in the photograph.

On full frame, wide angle focal lengths range from about 10mm (uncommon and excessively wide for many uses) to 35mm (which is long enough that some photographers consider it a normal lens rather than a wide-angle).

NIKON Z 7 + NIKKOR Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S @ 24mm, ISO 400, 1/320, f/11.0

Telephoto Lens Power

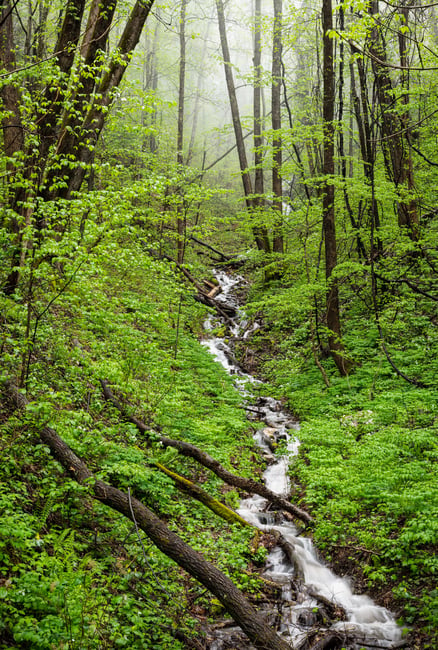

A telephoto lens is like looking through binoculars – it has the power to bring your subject up close and personal. A telephoto has a selective angle of view and is commonly used to photograph more distant subjects such as wildlife or sports. It can also make pleasing head and shoulders portraits of people from a relaxed and comfortable distance.

If you can’t get close to your subject, chances are you will want a telephoto lens. They are my personal favorite lens type for landscapes, where I can compose a picture of a photogenic section of a forest rather than taking in the entire hillside. Telephoto focal lengths begin at 70mm and continue up to about 800mm.

NIKON Z 7 + 150-600mm f/5-6.3 @ 600mm, ISO 160, 1/160, f/10.0

Specialty Lenses

Within the broad categories of wide angle, normal, and telephoto lenses, there are also more specialized optics. For example, a macro lens is designed to focus very close so that tiny objects such as insects, flowers, or jewelry can fill the frame. Another specialty lens is the high-speed (or fast) lens, which has larger lens elements and a wider maximum aperture – great for letting in more light and capturing very shallow depth of field photos, where not much in the image is in focus.

Other speciality lenses included fisheye with its extreme and distorted field of view, tilt/shift lenses which are used by some architectural, studio, and landscape photographers to more precisely control perspective and focus, and the huge, exotic super-telephotos seen on the sidelines of major sporting events.

NIKON D7500 + TAMRON SP 90mm F2.8 Di Macro VC USD @ 90mm, ISO 400, 1/200, f/5.6

Primes vs Zooms

A prime lens has a single focal length, such as the 50mm normal lens. A zoom lens has a range of continuously variable focal lengths, such as a 24-105mm lens. You turn the zoom ring on the lens barrel to zoom in from a wide-angle 24mm perspective toward a telephoto 105mm.

Prime lenses are often smaller and lighter than zooms, and they often have a larger maximum aperture. Prime lenses also tend to provide somewhat better optical quality than zooms. But zoom lenses win the convenience award, allowing you to carry one lens that replaces a whole bag of fixed focal length primes.

The very best zoom lenses these days are so good optically that most photographers will not need to worry about the optical differences. Both primes and zooms can have their proper place as a photographer’s lens kit grows.

Price vs Performance

Lenses come in all price ranges, and good options exist in the budget range. Spending more money may get you a higher level of build quality, more refined optical qualities, or wider apertures, but for the beginner, there is no reason to overspend.

Any modern lens should allow you to take pictures as excellent as your skills allow. If you do continue to enjoy photography and develop your skills, a time may come when spending more money will get you an upgrade in one of the aforementioned areas.

NIKON Z 9 + NIKKOR Z 24-120mm f/4 S @ 58mm, ISO 64, 20/1, f/16.0

OEM vs Third Party

Each camera manufacturer such as Canon, Nikon, and Sony has its own line of lenses designed to fit its specific cameras, and most of these lenses tend to be very good to excellent and are a safe choice. But there are also third-party, lens-only manufacturers such as Sigma and Tamron who are turning out great optics and usually at lower prices than the OEM lenses. Perusing the lens reviews here at Photography Life will help give you ideas of what lenses are available and how they measure up.

New vs Used Lenses

New lenses are a safer bet as you usually have 30-day return privileges if not satisfied, and you don’t have to wonder how the lens was treated by previous owners. You also have a manufacturer’s warranty if you purchase from an authorized dealer for the brand you choose.

For bargain hunters, used lenses can bring the reward of money saved, but there is the risk of getting a lens that does not perform as it should. There are a wide variety of potential issues with precision products like lenses, such as a lens element that is out of alignment, autofocus motors dying, dust or mold inside the optics, or wear and tear on the barrel.

I advise beginners to buy new, or make sure there is a return privilege for used lens purchases purchased from a reliable seller (B&H Photo is an excellent choice for new and used; KEH Camera is great for buying used with good warranty).

NIKON Z 7 + Nikkor AI-S 55mm f/2.8 @ 55mm, ISO 64, 1 second, f/16

Choosing One Lens to Start With

Armed with this basic introductory info about lenses, now the fun begins: choosing your first one.

The classic, disciplined approach argues for a 50mm normal lens, and these have the advantage of being among the most affordable, lightweight, small, bright (AKA wider aperture), and optically excellent lenses in any manufacturer’s line. As a beginner, using a 50mm lens for a wide variety of photography will teach you much about what your own needs are for your ultimate lens kit. If you photograph in small spaces, you may eventually see the need for a wide angle, or if you spend much of your photography taking pictures of children’s soccer, you’ll soon understand the need for a telephoto. A 50mm standard lens is a great teacher.

If you want to photograph a wide variety of subjects with convenience, a more versatile first lens purchase would be a wide-to-telephoto zoom, something like a 24-105mm or 28-200mm. With zooms like this, you’ll have all the most important focal lengths covered in one package, and you just need to turn the zoom ring to find the right perspective for your subject.

The more modest the zoom range, the better optical quality tends to be. 24-70mm lenses usually beat 24-120mm lenses, which usually beat 24-200mm lenses. (They also tend to be lighter and/or have a larger maximum aperture.) I find that 24-105mm and 24-120mm lenses are the best compromise. They’re not just a good first lens for beginners, but also a beloved optic any time you need a versatile lens on your camera. I use a 24-120mm f/4 constantly on my own system.

NIKON Z 7 + NIKKOR Z 24-120mm f/4 S @ 120mm, ISO 560, 1/25, f/4.5

To add a bit of discipline as you’re starting out with a zoom lens like this, I recommend a beginner take the 24-105mm zoom and for the first few months of their photography only use the lens at three marked focal length settings: 24, 50, and 105mm. It will be as if you have three primes in your bag, and you’ll learn from this exercise how to choose the focal length to suit the perspective and composition you want for each subject.

If you are a beginner who already knows you are going to be spending most of your camera time photographing sports or wildlife, and you only want one lens to start with, then consider bypassing the wide and normal views and choose a 70-300mm or 100-400mm as your first lens. This way you are equipped with the telephoto range needed for distant subjects, and you can use your iPhone for the normal and wide views when taking family snapshots or vacation pics.

Building A Multi-Lens System

Here’s where it gets more fun! If you plan from the start to build a system of two or more lenses, you can expand on my recommendations above and use multiple lenses that complement each other.

If choosing the versatile 24-105mm recommended above, lens number two (when you’re ready) could be a 100-400mm to get a telephoto perspective, a 50mm f/1.8 to get a wider aperture, or a 16-35mm to get a wider angle view.

Alternatively, nature lovers may eventually want a macro lens to help capture close-ups of the tiny world, and a 100mm macro is a superb complement for almost any other lens kit. Since most macro lenses have a large maximum aperture of f/2.8 or so, they can also double as a portrait lens that offers a nice, shallow depth of field effect. Or you can go to more exotic fast-aperture primes if portraiture is your specialty, such as a 85mm f/1.2 or 135mm f/1.8.

NIKON Z 7 + 70-200mm f/2.8 @ 80mm, ISO 64, 1/160, f/8.0

Enjoy the View!

Lenses are the life of the interchangeable lens camera, and truly the best way for a beginner to expand their vision through the virtually limitless world of optics. From the drama of wide angles, to the just-right comfort of the standard lens, to the powerful world of telephotos, the view from a good lens is seductive and just may lure you into the joy of photography for the rest of your life.

I hope you’ve glimpsed the fun that can await you as a beginner looking to choose your first lens or build a multiple lens system. I welcome your comments below!

Every article that helps beginners is useful and this is very inclusive. I have some notes to make:

1) regarding of third party lenses. After many years using exclusively Tamron and Canon lenses (i have Canon cameras btw) i have to tell you that for beginners the best choice is to stick with a kit lens as much as possible OR, if the budget allows, go for in house glass. Why? Simply because the AF will never be as reliable, and if you are a beginner you will not be able to judge any misfocus by the camera screen! My favorite telephoto is Tamron 70-210 f/4. I have shot some of my best photos with this lens and, still, i cant trust its AF accuracy even after many hours of tweaking with the TAP-in Console. The results are better on Live View with the Dual Pixel AF but even then i missed some critical shots. Same was true with other Tamron lenses also. On the other hand, with Canon lenses i had never AF issues even on -3 EV situations.

2) I ‘ve read some comments bellow about APS-C vs FF for beginners. That conversation is hazardous. Chances are that a person who buys his first camera will not even know what the focal length 18-55mm means… not to mention the usage of a full frame mirrorless! Also, full frame cameras means more expensive lenses (that again, a beginner doesn’t know how to use), more demanding files to edit so the need for more computational power, and in general, i don’t believe that 80% of non pro photographers need a full frame sensor. From personal experience, i find myself to use most of the time my APS-C DSLR rather than my FF because of the ergonomics and the crop factor (i am used to shoot on 80mm quite a lot and i have a Zeiss Planar 50mm so i don’t need to buy the 85 also). If you pair a modern APS-C camera with a quality glass you are not gonna notice any difference with FF (except on ISO 3200+).

Hi forneverarrow, thank you for the positive feedback and for sharing your perspective!

In the past 15 years I have owned 9 different cameras from 4 different systems, and have owned more than 50 lenses. What I wish someone had told me when I started was to just go full frame from the start, and to start with 4 lenses that allow you to create images different than what our eyes can see. To buy an ultra wide zoom, a 58mm f/1.4, a 100mm macro, and a 100-400mm zoom.

That would be my advice for new photographers. Make the investment in really great gear, and don’t shoot with “normal” lenses that provide the same boring perspectives as smartphones. Shoot ultra-wide, macro, long telephoto and ultra-bokeh to make your photos stand out from the crowd.

I read a very funny article along those lines a few years ago.

It was a mock ‘agony’ column in which a reader wrote in for buying advice on a £500 budget. The advice was to get a top end camera with 35/f2 and 135/f2 lenses. The outraged reader said that’d cost several £000. The calm columnist suggested that it was what he’d get in the end and that the total cost of all the buying and selling involved to get there would cost a lot more than buying it in the first place.

I do have the ultra-wide, I have a 180 macro, I might get an 85/f1.8 and a 200-500 is on the list.

But I am very fond of my aps-c D7500.

Thanks for sharing your perspective Anon_42.

Kind of an odd article as a “beginner” probably wouldn’t be shooting with a Z7 or D850, and more likely an APS-C format. The reason I mention it is, converting your advise to a smaller format’s lenses may be confusing, if they’re even aware of the need to do so, and while you mention the conversion factor, I think giving examples would have been more useful.

Hello Pat, thanks for taking the time to read and comment. To be clear this article did not recommend shooting a Z7 or D850 – we specifically avoided recommending any particular model of camera as it was beyond the scope of a piece written to help a beginner understand the basics of lenses, which is applicable knowledge regardless of camera brand, model, or format.

APS-C dominated the beginner camera market in the past but things are changing rapidly in the industry due to the encroachment of cell phone cameras – now the market is pushing hard toward full-frame format and mirrorless. Thankfully there are excellent entry level full-frame options from Canon, Nikon, and Sony. One of the best is the Z5 that Nikon has been putting on sale a couple times of year for only $999 – a tremendous value.

I understand your first point, but people will still look at the photos and make some kind of association with the article. As for your second point, I’ve seen the push but in my, admittedly limited, experience, most beginners aren’t going for FF. On the other hand, most people shooting APS-C aren’t looking to buy additional lenses, either.

I agree with Ross. If I were advising a beginner I’d recommend 1) a used D7100 or D7200 and a 16-85 or 18-140 and 2) spending less on the phone – you only need to spend so much to make calls, send texts, take snaps and watch YouTube videos.

Strongly disagree. There is little development going on in APS-C. If a beginner sticks with the hobby, they’re going to eventually want to move on to something more modern eventually.

Personally, having started in digital photography with a Nikon D7000 about 12 years ago, at this stage I’d recommend a beginner go with one of the lower end MILC FF options; the ability to see the results of your exposure settings will really help a beginner visualize the exposure triangle. A used Z6 or Z5 is the way to start off in Nikon these days, IMO. Plenty of cheap 24-70 f/4 lenses out there, but I’d recommend the 24-200 if one can afford it.

The extra cost to start with a modern FF system will pay dividends later if they choose to continue to pursue photography. If they don’t, reselling Nikon Z equipment will be easier as well, IMO.

This is coming from someone whose primary cameras are still a D500 and D850.

Hi Joseph, well said, we share a similar perspective.

That’s maybe true for Nikon, but for Canon or Sony things are different. I am using Canon DSLRs for ages now and I am still skeptical to move on mirrorless. The reason? RF mount! I know, I can buy the adapter and have my EF lenses but what’s the point then? The cheapest way to enter the Canon FF mirrorless system is the EOS RP and with a basic 24-140mm RF you must pay about 1700€ (at least in my county). To the contrary there’s the top of the line apsc DSLR, the 90D with a kit lens and the ability to use any EF lens for 899€. Spec for spec the 90D is a better camera except the sensor size (but it has 32 over 26mp). For a beginner the better ISO performance doesn’t matter as much over the weather sealing, the battery life and the ability to crop further (32mp over 26).

As for me, the RP isn’t a choice to replace my 5Dmk4, not even the heavily discounted EOS R. The only choice is the R5 that costs 4000€ body only… I am telling this because not everyone is a Nikon user.

Er … Fuji?

‘Results of exposure settings’? Every camera we’re discussing will do that.

A D7100 and 18-140 will cost half (maybe less) of a used Z5 – which at the moment costs pretty much the same as a new one. I know – I’ve just bought one.

Beginners tend to be on a small budget.

I should have been more clear; what I was referring to is instantly seeing the results of your exposure settings live in the viewfinder before you even take a picture. Yes DSLRs have Live View on the rear screen but I do not enjoy working that way.

Now I’ve had a go with the Z5, which cost the same as my D7500 when both were new, I know which I’d direct a beginner to – the D7500. And without any hesitation.

If I could only own one of them, that’s the one I’d keep.

A beginner doesn’t know which direction they’ll end up going in, so they need a versatile camera to explore all types of photography.

If the Z5 has an advantage in high ISO IQ and EVF, the D7500’s has superior metering and action autofocus, which IMHO more than makes up for it – especially if you want an all-round camera.

I’d agree that Nikon has underinvested in dx lenses, but they are more than good enough to start off with. I still look at A3 prints of images taken with my 6mp D50 and Sigma 18-50/f2.8 and think: ‘pretty darn decent’.

I tend to agree. I’m still happily shooting away with a D7100, and my wife a D7200. If our images aren’t good enough, I think it’s more the fault of the taker than the machine. Better, overall, or at least as good, as when we were shooting slides. By some standards we’re dinosaurs using even that recent stuff, but if the goal is to take good pictures, it’s met pretty well at a bargain price.

It’s true, unfortunately, that Nikon has stinted on DX lens development, but the ones they’ve done are very good. When my wife originally bought the D7100 I now have, it came with the 18-140 as a kit lens, and that’s turned out to be a very good performer. She keeps that on her D7200 and I have the superb 16-80 (I had the 16-85 but it was a very used gray market one and it conked out). We both have the FX version of the 70-300P and this is also fine and good for travel. My main complaint about DX, that it’s hard to find a decent wide angle, was largely answered by the bargain 10-20 DX lens.

I prefer the meter coupling that’s lacking on the D7500 because I like to play with older lenses, though I was able to do so before with a meterless D3500 and could again. But I like being able to meter automatically even with the uncoupled 35/2.8 PC.

I keep looking at new cameras but there’s not enough more that I need. I used a Nikon F until something like 2010, because I kept saying I’d get a newer camera when the F wore out. Ha. It never did, of course, and now I’m suspecting the D7100 will be the same.

Very good article, very explanatory.

On my mind, the first that comes for me at this right time, is the Z40mm F/2.

But 35mm is a must have anyway.

Then, the 135mm F/2 from Canon (whatever is the camera behind), then a 70-200 or 70-300… then the 500 PF… and I’m done.

But I love to play with some others too, of course.

Thanks again and have a nice week-end

Hi Pierre, thanks for your feedback and I’m glad you enjoyed the article. Those are some enticing lenses you mentioned!