No matter what digital camera you shoot with nowadays, you must have some kind of storage where your media is going to be saved to. While some devices like phones and tablets often come with some built-in memory, you will often find yourself looking for ways to expand that storage by using memory cards or other external storage accessories. And if you shoot with a dedicated digital camera, you will find that it does not offer any kind of storage and you will need to buy at least one memory card in order to be able to store captured images. That’s how a quest for selecting the best memory card begins. Choosing memory cards can be a very frustrating experience, since there are so many different types of memory cards with so many different features and price points. In this article, we will explore memory cards in detail and give you everything you need to know about them.

First, we will define memory cards and explore the different types of memory cards available. Then we will go over the different classes of memory cards. After that, we will show you ways how to read and understand information written on memory cards. And lastly, we will give you some of our tips and recommendations on selecting and using memory cards.

Table of Contents

What is a Memory Card?

A memory card is an electronic storage device used for storing digital media, such as photos and videos. In photography, memory cards are commonly used in digital cameras, varying in type, form factor, capacity, speed / class and brand. The most common memory card formats today are SD, microSD, XQD and CFexpress, although CompactFlash was also a very common memory card format for many years.

Memory Card Types / Form Factors

Here is a quick summary of different types of memory cards available on the market today, along with their dimensions and abbreviations:

| # | Memory Card Name | Abbreviation | Dimensions (WxLxH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Discontinued / Uncommon | |||

| 1 | Secure Digital 1 | SD | 24.0 x 32.0 x 2.1mm |

| 2 | Secure Digital High Capacity | SDHC | 24.0 x 32.0 x 2.1mm |

| 3 | Secure Digital Extended Capacity | SDXC | 24.0 x 32.0 x 2.1mm |

| 4 | microSD / microSDHC / microSDXC | microSD / microSDHC / microSDXC | 11.0 x 15.0 x 1.0mm |

| 5 | Memory Stick, Memory Stick PRO 1 | MS | 50.0 x 21.5 x 2.8mm |

| 6 | Memory Stick Duo / PRO Duo / PRO-HG Duo | MSD / MSPD / MSPDX | 20.0 x 31.0 x 1.6mm |

| 7 | CompactFlash Type I | CF-I | 42.8 x 36.4 x 3.3mm |

| 8 | CompactFlash Type II 1 | CF-II | 42.8 x 36.4 x 5.0mm |

| 9 | CFast | CFast | 42.8 x 36.4 x 3.6mm |

| 10 | XQD | XQD | 38.5 x 29.8 x 3.8mm |

| 11 | CFexpress | CFexpress | 38.5 x 29.8 x 3.8mm |

It is important to note that the above table is limited to the most popular memory cards and form factors used on digital cameras and camcorders. Many other memory card types were introduced and then abandoned over the years, but we did not list them all.

Secure Digital (SD)

Secure Digital cards, or shortly “SD cards” were jointly developed by SanDisk, Panasonic and Toshiba and introduced in 1999 for use in portable devices. The three companies later formed the SD Card Association to create, promote and enforce SD card standards across the industry. With a fairly small size of 24.0 (W) x 32.0 (L) x 2.1mm (H), relatively low cost of production and adoption by many manufacturers, SD cards quickly became an industry standard. However, due to file system and other limitations, SD cards could only hold up to 2 GB of data maximum, so new standards had to be developed in order to allow larger capacity memory cards. The nice thing about the SD card specification, is that it allowed the SD Card Association to keep the same physical dimensions and appearance, while being able to create newer generation SD cards with higher capacities and speeds. Today, the original SD cards have been fully discontinued and they have been replaced by the newer-generation SDHC and SDXC cards. Quick Summary: Obsolete format, move on to SDHC or SDXC cards.

Secure Digital High Capacity (SDHC)

With a 2 GB capacity limit, the original SD cards were obviously no longer sufficient, so the SD Card association had to come up with a new specification that allowed larger capacity cards. In January of 2006, a new standard was developed that not only increased card capacity to up to 32 GB in size, but also doubled the performance of the cards, allowing much faster read and write speeds. This standard was named “Secure Digital High Capacity”, indicating the increased capacity of these cards. Unfortunately, older SD card readers in cameras and computers were not compatible with SDHC cards, until their firmware was updated to be able to support the new card standard, whereas SDHC memory card readers were backwards compatible to be able to read both SD and SDHC memory cards. SDHC cards are fairly common to find on the market, although they might soon be phased out by the larger SDXC cards. Quick Summary: You can get older UHS-I and newer UHS-II (more on UHS under Memory Card Speeds) SDHC memory cards, but be warned that SDHC is limited to 32 GB cards only – anything of larger capacity will have to be SDXC.

Secure Digital Extended Capacity (SDXC)

With a maximum capacity of 32 GB (mostly imposed by the limited FAT32 file system) and newer devices pushing a lot more data, especially when capturing high bitrate video, it was time to move up to a new and improved standard and that’s how Secure Digital Extended Capacity (SDXC) was born. Maximum card size was increased to theoretical 2 TB maximum (2048 GB) and the file system was switched to exFAT, developed by Microsoft. The newest SDXC standards are very robust, allowing fast transfer speeds of up to 624 MB/sec using UHS-III bus. Quick Summary: If you need SD memory card capacities above 32 GB, SDXC is the only way to go. Whether you choose SDHC or SDXC does not matter – the bus speed (UHS-I, UHS-II, UHS-III) and the rated memory card speeds for both read and write operations are going to be more important.

microSD / microSDHC / microSDXC

microSD memory cards were born due to SD cards being too big for mobile phones. Initially developed by SanDisk, microSD was later on embraced and standardized by the SD Card Association, which announced the form factor in 2005. The initial microSD memory cards were slow and their capacities were limited to 2 GB due to the FAT16 file system, just like SD cards. However, the SD Card Association was quick to release the next generation SDHC cards that lifted those limits. And with the introduction of SDXC that took advantage of the exFAT file system, it became possible to make cards larger than 32 GB in size, with much faster read and write speeds. microSD cards quickly gained popularity among portable device manufacturers for their small size – at just 11.0 (W) x 15.0 (L) x 1.0mm (H), these cards are the smallest memory cards available on the market today and they have been embraced by many mobile phone and tablet manufacturers. Quick Summary: microSD is a popular format for small portable devices, so if you have a phone or a compact camera that utilizes microSD cards, you will need to buy microSDHC or microSDXC cards.

Memory Stick / Memory Stick PRO

Sony introduced the Memory Stick in 1998 and started using it on Sony cameras, camcorders, PCs and PlayStation Portable devices as a proprietary memory card format. Although these memory cards were initially available in small capacities, a newer revision of the card in the form of Memory Stick PRO was introduced in 2003 that expanded memory capacity even further. With a fairly large footprint of 50.0 (W) x 21.5 (L) x 2.8mm (H) and high pricing, these memory cards could not get enough traction to be able to gain a significant market share when compared to SD cards, so Sony had to come up with ways to decrease the physical size of the cards. Both Memory Stick and Memory Stick PRO cards were therefore short-lived, with Memory Stick Duo form factor taking over. Quick Summary: Both Memory Stick and Memory Stick PRO cards have been obsolete for many years now and you can no longer purchase them from most retailers.

Memory Stick Duo / PRO Duo / PRO-HG Duo

With the introduction of Memory Stick Duo form factor that measured smaller than the original Memory Stick at just 20.0 (W) x 31.0 (L) x 1.6mm (H), Sony thought that it could compete directly with the SD format and capture a larger market share of the memory card market. Unfortunately, due to Sony’s higher pricing strategy, the plan did not work out and Sony lost most of its market share to SD, which later became the most popular memory card format on the market globally. Still, Sony continued to push the Memory Stick to its own products, eventually coming up with faster and higher capacity memory cards like Memory Stick PRO Duo and PRO-HG Duo, which offered much faster transfer rates of up to 60 MB/sec and theoretical capacities up to 2 TB. Today, Sony is the only memory card manufacturer that continues to produce and support these cards. Quick Summary: Sony lost the memory card war to SD and all of its Memory Stick products are a thing of the past.

CompactFlash Type I (CF-I)

CompactFlash (CF) was first introduced by SanDisk in 1994 and it quickly gained traction compared to all other formats of its time, because it offered solid performance and it was not as prone to bending or breaking as some other memory card types, thanks to its denser shell construction. As a result, a number of camera manufacturers like Nikon and Canon adopted CF as their standard in high-end cameras, making CF popular among enthusiasts and professionals. CompactFlash Type I (CF-I) memory cards are the most common and have dimensions of 42.8 (W) x 36.4 (L) x 3.3mm (H) – these are the memory cards that were widely adopted by many cameras and portable devices. The biggest issue with CF cards turned out to be their large size and pins, which are prone to bending on memory card readers. Another limitation of CompactFlash is that it utilizes the slow Parallel ATA / IDE bus. Despite the introduction of newer CF-I revisions that allowed these cards to reach up to 167 MB/sec speeds in Ultra DMA Mode 7 (more on CF memory card speeds below), the bus itself imposed the limit on maximum throughput. As a result, new standards had to be developed to move away from CF cards. Quick Summary: Unless you have a camera that still uses CF cards, you should not be looking into them, since they have already been replaced by much faster CFast, XQD and CFexpress memory cards.

CompactFlash Type II (CF-II)

CompactFlash Type II (CF-II) memory cards were developed in order to allow memory cards to be used as “microdrives” (miniature hard disks) or adapters to read other memory cards. Therefore, the only difference between CF-I and CF-II is the physical height. CF-I cards have a height of 3.3mm, whereas CF-II cards are a bit thicker at 5mm. Both use exactly the same type of connection, but since CF-II cards are physically thicker, memory card readers need to be able to accommodate them. Since the idea of microdrives never got real traction and faster flash memory took over due to lower cost, capacity and reliability, most manufacturers including Nikon ended up dropping support for CF-II cards in their cameras. Quick Summary: CF-II cards are not even available to buy, since CF-II format was only developed to be used for microdrives and memory card adapters.

CFast

To get away from the slow Parallel ATA / IDE bus, a new CompactFlash memory card variant called “CFast” was invented, which utilizes the much faster Serial ATA bus. The first version of CFast (1.0 / 1.1) allowed to reach up to 300 MB/sec speeds, whereas the newer CFast 2.0 standard released in 2012 took advantage of the Serial ATA 3.0 bus, doubling the throughput potential to up to 600 MB/sec. It is important to point out that although the physical dimensions of CFast cards are very similar to those of CompactFlash cards, they are not backwards compatible due to differences in interfaces. Unfortunately, the mass adoption of CFast was too slow (aside from the Canon 1D X II, the Hasselblad H6D-100C and a handful of video recording cameras, no other products have adopted CFast) and as of 2016, it has already been technically replaced by the newer and much faster CFexpress standard. Again, the bus was the biggest reason why CFast had to go. Quick Summary: CFast is already dead, since it has been replaced by the new CFexpress standard based on the XQD form factor, so do not waste your money by buying these cards.

XQD

XQD was a new memory card form factor introduced in 2010 by SanDisk, Sony and Nikon. Since it is based on the fast PCI Express interface, it clearly stood out from all other memory cards developed before, so it was immediately picked up by the CompactFlash Association for development. Essentially, XQD replaces both CompactFlash and CFast as the new form factor. With its 38.5 (W) x 29.8 (L) x 3.8mm (H) dimensions, it is physically smaller than CompactFlash / CFast cards and it has a much superior build than both SD and CF cards, since the cards are denser than SD and they no longer utilize pins on the host that could easily break or bend. Among camera manufacturers Nikon was the first to standardize on XQD cards with its Nikon D4, D4S, D5, D850, D500, Z7 and Z6 cameras using single or dual XQD memory slots. Although the first N-Series XQD cards were limited to 125 MB/sec read and 80 MB/sec write speeds, the last generation G-Series XQD cards have been able to reach much faster 440 MB/sec read and 400 MB/sec write speeds. With the XQD version 2.0 standard, the maximum theoretical throughput of XQD cards was pushed up to 1 GB/sec, although no such cards exist today. Similar to CFast, XQD has also seen a very slow adoption rate. Quick Summary: XQD is fast and capable, but it will be replaced by CFexpress.

CFexpress

In September of 2016, the new CFexpress standard was announced, which is capable of utilizing NVMe storage for low overhead and latency, capable of pushing almost 2 GB/sec. The first iteration of CFexpress uses the XQD form factor, but requires a CFexpress capable reader/writer on the host. Some cameras, such as the Nikon Z6 and Z7 were initially released only with XQD memory card support despite having a CFexpress compatible memory card slot. Nikon subsequently released a firmware update to bring CFexpress compatibility to these cameras (firmware version 2.20), and promised to release similar firmware for other Nikon DSLRs with XQD cards. Considering the technology present in CFexpress cards, they will become the gold standard for most high-end devices in the future. Quick Summary: CFexpress is currently the fastest and the most capable memory card format on the market, and will likely be the default choice for future-generation stills and video cameras.

Memory Card Sizes

Memory cards obviously come in different sizes. While older memory cards were limited to megabytes, newer memory cards are much larger in comparison and can be commonly found in 64 GB and larger sizes. Some of the latest generation memory cards offer 512 GB memory card capacities. Memory card capacity is typically clearly indicated on top of every memory card and you should be able to easily find it. If you are wondering how big of a card you should get, it really depends on a number of factors such as: what you shoot, how much resolution your camera has, whether you shoot RAW or JPEG, what RAW compression option you use when shooting RAW and whether you shoot a lot of continuous action. For example, a 16 GB card might be sufficient for a portrait photographer who shoots selectively with a medium resolution camera, whereas a wildlife photographer who shoots many bursts of images, or a landscape photographer who takes high-resolution panoramic images might find even 64 GB memory cards to be somewhat limiting for their needs.

Memory Card Speeds

Memory cards can also vary greatly in speed, or how fast they can read and write information. Unfortunately, this is where things can get quickly confusing, because speed ratings and how they are marked vary greatly by memory card type. In this section, we will take a look at how memory card speeds are marked on SD, CF and XQD / CFexpress memory cards.

SD Memory Card Speed Classes

The SD Card Association came up with a way to define SD card speed through something called “Speed Class”, which defines minimum sequential writing speed a memory card can provide. In addition to that, there is also bus speed, which is typically defined as something like “UHS”, which shows the theoretical maximum a card can provide over the bus. There are also UHS Speed Class and Video Speed Class specifications, which define minimum sequential write speeds even further. Let’s start by looking into different bus interfaces and their limits. Below is a short table that summarizes different bus interfaces and their potential bus speeds:

| Bus Inteface | Compatible Memory Cards | Maximum Bus Speed |

|---|---|---|

| High Speed | SD, SDHC, SDXC | 25 MB/sec |

| UHS-I | SDHC, SDXC | 104 MB/sec |

| UHS-II | SDHC, SDXC | 312 MB/sec |

| UHS-III | SDHC, SDXC | 624 MB/sec |

As you can see, there is a big difference between High Speed, UHS-I, UHS-II and UHS-III cards in terms of maximum bus speed. While the original cards were pretty much capped at 25 MB/sec, the UHS-I bus interface lifted that to 104 MB/sec and the newer UHS-II bus was able to triple that potential at 312 MB/sec. The newest UHS-III standard is very new, but it enables insane theoretical speeds of up to 624 MB/sec.

It is important to understand that cards with a faster bus speed also require a memory card reader / writer that can support that bus speed. For example, if you purchase a memory card with a UHS-II bus interface, the memory card slot on your camera must also be UHS-II compatible, or you will experience all kinds of performance and reliability issues. The same goes for a memory card reader on your computer – it also must be UHS-II compatible in order to support the higher speeds.

Besides the bus interface, you might also find other speed classes that are marked on SD memory cards. Let’s go over those now:

| Minimum Sequential Write Speed | Speed Class | UHS Speed Class | Video Speed Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 MB/sec | |||

| 4 MB/sec | |||

| 6 MB/sec | |||

| 10 MB/sec | |||

| 30 MB/sec | |||

| 60 MB/sec | |||

| 90 MB/sec | |||

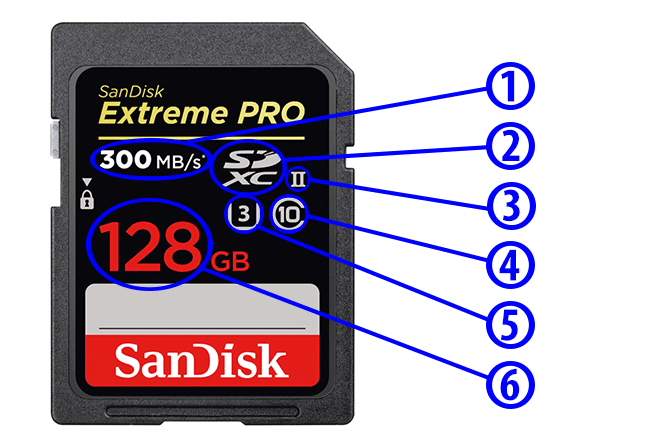

This all sounds pretty confusing doesn’t it? Well, those are the markings you will commonly find on many SDHC and SDXC memory cards out there. Let’s take a look at a real memory card and see if we can make some sense from all the information provided on it:

- Maximum Read Speed – This is the maximum sequential read speed the memory card is capable of in Mega Bytes per second (MB/sec). Please note that write speeds are rarely ever published on memory cards and you will need to find that information in memory card manual or listed specifications. In this case, the maximum read speed of the SD card is 300 MB/sec.

- Type of SD Memory Card – You should also be able to locate the proprietary SD card logos on memory card labels that indicate whether the card is of SD, SDHC or SDXC type. In this particular case, it is an SDXC memory card.

- UHS Bus Speed – UHS bus speed is also often published directly on memory card labels. If it is a UHS-I card, you will just see roman numeral one (I), whereas if it is a UHS-II card, you will see roman numeral two (II), as in the case of the above card.

- SD Speed Class – This number indicates what SD Speed Class card it is, per table above. As in the above case, all modern SD cards should be rated at 10 minimum, which guarantees minimum sequential write speed of 10 MB/sec.

- UHS Speed Class – Aside from UHS bus speed, you will also typically find a UHS speed class label. In this particular example, I can see that the card is rated at minimum 30 MB/sec write speed, thanks to this U3 label.

- Memory Card Capacity – The capacity of the memory card is typically displayed in large numbers. As can be seen here, this memory card has a total capacity of 128 GB.

Now that you can read SD memory cards, let’s take a look at CompactFlash cards and how you can read them.

CompactFlash Card Speed Classes

Unfortunately, memory card speeds and classes can vary greatly depending on what form factor you are looking at. As explained above, CompactFlash cards use Parallel ATA / IDE bus and therefore their speed ratings are influenced by the maximum potential speed of the Ultra DMA interface, just like with older hard drives. Below is a table that summarizes 7 different Ultra DMA modes with their corresponding maximum transfer rates:

| Ultra DMA Mode | Also Known As | Maximum Transfer Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra DMA 1 | 25 MB/sec | |

| Ultra DMA 2 | Ultra ATA/33 | 33.3 MB/sec |

| Ultra DMA 3 | 44.4 MB/sec | |

| Ultra DMA 4 | Ultra ATA/66 | 66.7 MB/sec |

| Ultra DMA 5 | Ultra ATA/100 | 100 MB/sec |

| Ultra DMA 6 | Ultra ATA/133 | 133 MB/sec |

| Ultra DMA 7 | Ultra ATA/167 | 167 MB/sec |

CompactFlash cards are technically limited by the fastest Ultra DMA mode 7, so it is impossible to develop faster CompactFlash cards in the future – they will always be limited to a maximum throughput of 167 MB/sec.

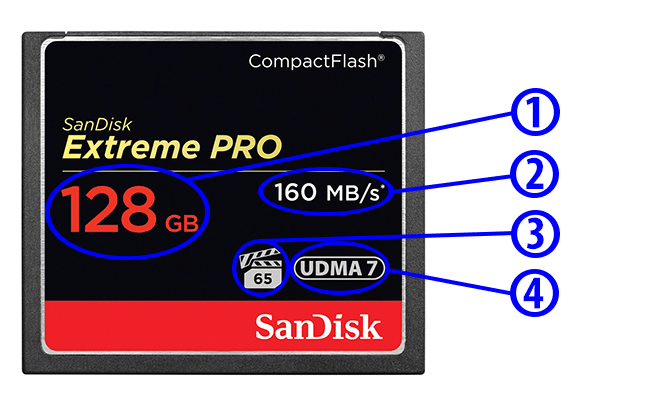

Thankfully, reading CompactFlash cards is a bit easier when compared to SD cards:

- Memory Card Capacity – The capacity of the memory card is typically displayed in large numbers. As can be seen here, this memory card has a total capacity of 128 GB.

- Maximum Read Speed – This is the maximum sequential read speed the memory card is capable of in Mega Bytes per second (MB/sec). Please note that write speeds are rarely ever published on memory cards and you will need to find that information in memory card manual or listed specifications. In this case, the maximum read speed of the SD card is 160 MB/sec.

- Minimum Write Speed – This is the minimum sustained write speed the memory card can deliver. As you can see, this particular card is guaranteed to be able to write at least 65 MB/sec.

- Ultra DMA Mode – Most cards will list their Ultra DMA Mode on the cover, which will give you a good indication of its potential. This particular CF card from SanDisk has Ultra DMA 7 mode, which is why it can reach top speeds of 160 MB/sec.

Modern cards are even easier to read in comparison. For example, CFast, XQD and CFexpress cards now fully list both read and write speeds right on memory card labels, so aside from those numbers, memory card capacity and perhaps memory card generation, you no longer have to worry about any other numbers that might need to be decrypted.

Memory Card Speed Comparison Table

Below is a summary of different memory card speeds, their versions and theoretical maximum speeds. We limited the table to card types that are in use today:

| Memory Card Name | Version | Bus | Launch Year | Max Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | UHS-I | 3.01 | 2010 | 104 MB/s |

| SD | UHS-II | 4.0 | 2011 | 312 MB/s |

| SD | UHS-III | 6.0 | 2017 | 624 MB/s |

| SD | SD Express | 7.0 | 2018 | 985 MB/s |

| CFast | SATA-300 | 1.0 | 2008 | 300 MB/s |

| CFast | SATA-600 | 2.0 | 2012 | 600 MB/s |

| XQD | PCIe 2.0 x1 | 1.0 | 2011 | 500 MB/s |

| XQD | PCIe 2.0 x2 | 2.0 | 2014 | 1000 MB/s |

| CFexpress | PCIe 3.0 x2 | 1.0 | 2017 | 1970 MB/s |

| CFexpress | PCIe 3.0 x4 | 2.0 | 2019 | 4000 MB/s |

As you can see from the above table, the only two standards that are seeing continuous updates are SD and CFexpress. However, based on the latest specifications from both, it is clear that CFexpress is going to have a huge advantage over SD in terms of maximum theoretical speeds.

Memory Card Brands and Recommendations

As of today, there are many different memory card companies that manufacture memory cards. Some of them truly manufacture memory cards, while others use the same OEM parts and simply slap their own labels on top. Some of the most recognizable names in the industry are: SanDisk, Lexar, Sony, Samsung, Transcend, Kingston, PNY Technologies, Toshiba, Delkin, ProGrade, Verbatim and ADATA.

Although there is no statistical data on failure rates of different memory card brands, my personal bias has always been with SanDisk – although it is probably one of the most expensive brands out there, I have never seen a SanDisk memory card fail on me. I mostly own SanDisk Extreme Pro series SD cards, and they have always been the cards I pick for important photo shoots. Lexar cards have been generally reliable, but I stay away from their SD cards due to previous failures (pins broke off, card failures, etc). Samsung and Sony’s Tough SD cards have also been great lately – they are fast and I have not experienced any failures yet.

This is obviously my personal experience with these brands and cards – your mileage might certainly vary and you might find one brand to be more reliable than another based on cards that have failed you in the past. It is also worth pointing out that memory card specifications and features change every year, so if you have experienced a problem with one particular model, it does not mean that the next model will be as bad.

Based on my research and my past experiences, failure rates among different memory card manufacturers vary greatly, and it is impossible to say that one brand will always be better than another. There are too many brands, too many models, too many features and too many memory card sizes out there to make meaningful statistical data that could compare different memory card brands for reliability. For me, brands like SanDisk, Samsung and Sony are trustworthy, because these companies have been known to make their own memory chips and their quality control is excellent. In comparison, many other brands simply slap their stickers on OEM memory cards…

Camera Memory Card Compatibility

With so many new cameras out today, it might be difficult to figure out exactly what type of memory cards they can support. Some cameras have a single memory card slot with particular specifications, while others have dual memory card slots, sometimes with completely different specifications. Below you will find a comprehensive table with popular modern cameras and their memory card slots, along with their specifications. This will hopefully make it easy for our readers to decide what memory cards are compatible with which cameras.

Please note that the cameras in the below table are listed alphabetically.

| Camera Model | Slot 1 | Slot 2 | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canon EOS R / Ra / Rp | SD UHS-I / II | ||

| Canon EOS 1D X Mark II | CF UDMA 7 | CFast | |

| Canon EOS 1D X Mark III | CFexpress | CFexpress | |

| Canon EOS 5D Mark IV | CF UDMA 7 | SD UHS-I | |

| Canon EOS 5DS / R | CF UDMA 7 | SD UHS-I | |

| Canon EOS 6D / Mark II | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS 7D Mark II | CF UDMA 7 | SD UHS-I | |

| Canon EOS 77D | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS 80D | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS M50 / M100 / M200 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS M5 / M6 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS M6 Mark II | SD UHS-II | ||

| Canon EOS Rebel SL2 / SL3 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS Rebel T5i | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS Rebel T6 / T6s | SD UHS-I | ||

| Canon EOS Rebel T7 / T7i | SD UHS-I | ||

| Fujifilm GFX 50R / 50S / 100 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | Up to 512 GB |

| Fujifilm X100 | SD UHS-I | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X100F | SD UHS-I | Up to 256 GB | |

| Fujifilm X100S | SD UHS-I | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X100T | SD UHS-I | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-E2S | SD UHS-I | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-E3 | SD UHS-I | Up to 256 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-H1 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | Up to 512 GB |

| Fujifilm X-Pro1 | SD UHS-I | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-Pro2 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I | Up to 256 GB |

| Fujifilm X-Pro3 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | Up to 512 GB |

| Fujifilm X-T1 | SD UHS-I / II | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-T10 | SD UHS-I | Up to 128 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-T100 | SD UHS-I | Up to 256 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-T2 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | Up to 256 GB |

| Fujifilm X-T20 | SD UHS-I | Up to 256 GB | |

| Fujifilm X-T30 | SD UHS-I | Up to 512 GB | |

| Leica Q / Q2 | SD UHS-I | Up to 64 GB | |

| Leica M10 / M10-D / M10-P | SD UHS-I | ||

| Leica SL | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I | Up to 512 GB |

| Leica SL2 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | Up to 512 GB |

| Nikon D3200 / D3300 / D3400 / D3500 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Nikon D4S | XQD | CF UDMA 7 | |

| Nikon D5 | XQD | XQD | 2x XQD or 2x CF UDMA 7 |

| Nikon D6 | XQD / CFexpress | XQD / CFexpress | |

| Nikon D500 | XQD | SD UHS-I / II | |

| Nikon D5300 / D5500 / D5600 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Nikon D600 / D610 / D750 | SD UHS-I | SD UHS-I | |

| Nikon D7100 / D7200 | SD UHS-I | SD UHS-I | |

| Nikon D7500 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Nikon D810 / D810A | CF UDMA 7 | SD UHS-I | |

| Nikon D850 | XQD | SD UHS-I / II | |

| Nikon Df | SD UHS-I | ||

| Nikon Z6 | XQD / CFexpress | ||

| Nikon Z7 | XQD / CFexpress | ||

| Olympus OM-D E-M1 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Olympus OM-D E-M1 II | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I | |

| Olympus OM-D E-M5 / II | SD UHS-I | ||

| Olympus OM-D E-M10 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Olympus OM-D E-M10 II / III | SD UHS-I / II | ||

| Panasonic G7 | SD UHS-I / II | ||

| Panasonic G85 | SD UHS-I / II | ||

| Panasonic GX85 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Panasonic G9 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | |

| Panasonic GH5 / GH5S | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | |

| Panasonic S1 / S1H / S1R | SD UHS-I / II | XQD / CFexpress | |

| Pentax 645Z | SD UHS-I | SD UHS-I | |

| Pentax K-1 / II | SD UHS-I | SD UHS-I | |

| Pentax KP / K-70 | SD UHS-I | ||

| Sony A7 / A7R / A7S | SD UHS-I | ||

| Sony A7 II / A7R II / A7S II | SD UHS-I | ||

| Sony A7 III / A7R III | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I | |

| Sony A7R IV | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | |

| Sony A9 | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I | |

| Sony A9 II | SD UHS-I / II | SD UHS-I / II | |

How to Store Memory Cards

After losing a memory card with the best pictures from a trip I took a while ago, I knew it was time to get organized, so that it does not happen again. Losing images from a long-planned and expensive trip can be very painful. After it happens, you realize that it is not the financial aspect of it, but the effort you put into creating those images instead that hurts the most. If you take all the steps you can to protect your photographs when traveling and working on the field, you can avoid losing precious memories and your valuable work.

1. Back Up Your Data

Whether you are a professional photographer or a photo enthusiast, it is critical to not only back up your existing data, but also the new data that has not hit your permanent storage yet. I always take either my laptop / iPad, or a storage device with me and back up photos from memory cards on a daily basis. Now when I say “back up”, I do not mean back up photos and then delete them from memory cards. You should never keep data in a single location, because any storage device can fail – it is just a matter of time. So when I back up my photos, I keep the originals on memory cards, until I safely get back home. Only after copying all images to my home storage and backing them up, I then format the memory cards for my next photography trip / job.

Backing up your data in the field can be done in several different ways. If your camera is equipped with dual memory card slots, you can configure your camera to write to both cards simultaneously. While this means wasting one card, it is a good idea, because two cards will contain the same images. If data is corrupted on one card or one of the cards is lost, you still have a backup on the second one. Memory cards are cheap, so if you do not need the speed for video or fast action photography, get multiple slower cards that you can use in parallel.

If your camera is not equipped with dual memory card slots, or if you want to still back up your data to a different location, consider backing up to a laptop or an external storage device. Backing up your photos to another storage device is always a good idea – what if you were to lose your camera, or if you dropped it somewhere you cannot recover it from?

2. Label Your Memory Cards

I typically label my memory cards and provide my contact information on them, if there is any available space on the memory card sticker. If your memory card does not have space to write on, just put some white tape on it (make sure to use thin tape and do not tape over contacts) and write your phone number. If anybody finds your memory card, they will at least have your contact information to contact you.

3. Use a Memory Card Holder

Keep your memory cards organized, and store them properly in your camera bag. There are many different memory card holders out there, but the one I personally use is the Pelican 0915 SD Memory Card Case that can hold up to 12 SD cards. This card case is water-resistant and well-protected against occasional abuse. If you have been storing your memory cards in camera bag pockets, I highly recommend getting one of these instead. When I lost one of my memory cards, it was because I temporarily put it into my pocket in rush. Storing memory cards in pockets or in camera bag pockets is not a good idea, since dirt, moisture and other elements could damage them.

If you only have one or two memory cards and do not want to purchase a card case, at least store them in plastic cases that came with the cards. When you are home and you are done using the memory cards, store them in dry, cool space (room temperature).

4. Mark Used Cards

I once formatted a used card with photos I needed, because I did not label or mark it after it was used. While you can recover photos from formatted cards, if you happen to write anything over the formatted card, the images you had before will not be recoverable, especially if you fill up the card with new images.

Personally, I simply flip memory cards over in my memory card holder after they fill up. This way, I know that I will not be touching those card until I get home.

How to Properly Use and Care for Memory Cards

The role of memory cards in a photography workflow should not be underestimated – a failed card may lead to many problems and frustrations. In my opinion, nothing is worse than telling a newlywed couple that their entire wedding was lost due to a bad memory card. While a commercial photo shoot can be re-shot, even at a great cost, it is nearly impossible to re-shoot a whole wedding.

Therefore, it is important to understand that a memory card is not just a simple storage accessory; its role as a reliable storage media tool should never be overlooked. Unfortunately, there is too much conflicting information on the Internet in regards to how one should use and treat memory cards, with very little evidence, which sadly leads to misunderstanding and misuse of memory cards in the field. Let’s explore some of these in greater detail and hopefully clear out some of the confusion.

1. Buy Reliable Brand Memory Cards

With so many different memory card brands out there at varying pricing levels, it might be tempting to go for a much cheaper, no-name brand card. However, before you make your purchasing decision, you should seriously decide if you are willing to deal with potential failures and problems of such cards in the future.

Also, factor in the cost of replacement – if you buy a no-name brand card and it fails, you will most likely be stepping up to get a much higher quality branded card, so your initial investment becomes a waste. If you start out with a good brand card and anything happens to it, you can count on the manufacturer’s warranty to get you a working replacement. Lastly, don’t forget to value your time as well! If a card fails, you might spend many hours trying to recover the content. Considering how cheap high quality memory cards have gotten nowadays, why even take the risk of choosing a no-name brand?

2. Buy Memory Cards From Authorized Sellers

Once you know which brand of memory cards you want to buy, make sure to buy those memory cards from authorized sellers. This one is even more important than #1, because there are too many fake memory cards out there!

Remember, all SD cards more or less look the same, so if someone slaps on a SanDisk label on an OEM card, you would have no idea that you are dealing with a fake memory card. Some Chinese manufacturers find ways to not only fake the memory cards themselves, but also closely imitate the original retail packaging, making the card look pretty authentic.

So if you found a card that you like at B&H Photo Video or Adorama, but the price looks a bit too steep for your liking, don’t fool yourself by thinking that you can find something much cheaper on eBay. Companies like SanDisk dictate their pricing with retailers, so if their pricing changes at one retailer, it should be mirrored with another (unless the sale is a one-off exclusive, such as the Deal of the Day at Amazon). If you shop for memory cards at Amazon, make sure that the card is sold and shipped by Amazon – there have been reported cases of fake memory cards being sold by third party sellers there.

3. Do not Buy Used or Refurbished Memory Cards

Even if you find a good deal on used or refurbished memory cards, I would highly discourage you from buying those. The problem with used and refurbished memory cards, is that you don’t know how frequently those cards were used before you. If the photographer used those cards heavily, it means that the memory card cells have less life left in them, so you might start encountering issues with those cards sooner than you would expect, especially if you are a busy photographer.

Unlike most cameras that can show you total number of actuations, memory cards do not keep a track of how many times write operations took place. So if someone tells you that their card was “barely used”, there is no way for you to check if the seller is telling you the truth. In addition, you don’t know how well the photographer took care of those cards, and forget about transferring the warranty under your name. Memory cards are incredibly cheap nowadays, so I would not try to save a buck or two by attempting to get used ones.

4. Pay Attention to Memory Card Specifications

Sadly, for most memory card manufacturers, it is all about the labels and the numbers they can slap on their memory cards to boost their sales, which means that you should not expect real, honest information on those labels. If a memory card says that it can do 95 MB/sec speeds, it does not mean that the memory card is actually going to be able to get to those speeds.

In fact, did you know that the published transfer numbers on memory cards often only reflect the read speed, but not the write speed? So if you see something like 95 MB/sec transfer rate on a memory card, that only shows the potential speed of the transfer from your memory card to your computer. The word “potential” is key here, because those advertised speeds are the maximum theoretical speeds a memory card can reach when doing sequential writes of large files.

Over the years, I found that most memory cards cannot reach their maximum advertised speeds, which is disappointing. So if you buy a memory card that claims fast read and write transfer rates, try to copy large-size files to and from the memory card to see if those numbers reflect the reality. But do make sure that you have a fast enough reader that can actually take advantage of those speeds (see #6 below for more information). I have tried to test out my SanDisk Extreme Pro cards that claim to have up to 95 MB/sec read and 90 MB/sec write rates and I have never been able to reach those speeds. At most I was able to get to was around 85 MB/sec read and 73 MB/sec write speed on those cards and they were the best of the bunch – others were even worse in comparison.

So when you are evaluating a memory card for purchase, don’t just look at the label – pay close attention to detailed specifications that show not just the maximum read speed, but also the maximum write speed. Then once you receive the card, make sure to test it out. If transfer speeds are incredibly slow, you might be dealing with a fake memory card!

5. Don’t Buy Large Capacity Memory Cards

Another tip for memory cards is not to buy the super large capacity ones. If you average a few hundred shots on your memory card, that’s good enough – you don’t need a memory card that can accommodate thousands of pictures (exception would be wildlife photographers, who shoot a lot of frames).

Why? Because if that super large capacity memory card fails, you will lose everything on it. This is especially important for those who shoot critical projects and events on a single memory card. If you have a trip of your lifetime, it might sound appealing to just use one single memory card and not worry about changing memory cards. But if anything happens to that memory card and you don’t have backups, then you will lose all the pictures from that trip. Unless you have a very solid backup workflow, where you make sure to back up images after each shoot, you should not stash on those large capacity memory cards.

Now if you have an advanced camera that has multiple memory card slots, having a single large capacity memory card could be useful. Many photographers use the second memory card slot as a “backup” and use a large capacity memory card in that slot without taking it out – they just replace the first memory card as needed. If you follow a similar practice, large capacity memory cards are not necessarily evil. Just don’t save all the precious work in one memory card without any backups!

Also, if you do shoot with multiple memory card slots in overflow mode (one memory card fills up and the camera starts recording to the second one), try not to delete images using your camera! When shooting in overflow mode and deleting images, you never know which particular memory card contains which photos – the camera will automatically place images in the first card that has the available space. The images might get mixed up, and you might end up with strange image sequences as a result.

How big should the capacity of memory cards be? Well, it all depends on the size of individual files your camera creates. If you shoot 14-bit uncompressed RAW on a high-resolution camera, your files are going to take a lot of space and you might need a bigger card to accommodate a few hundred of those images. If you shoot lossless compressed RAW files with a low to medium resolution camera, you might get away with smaller cards. When shooting with my Nikon and Fuji cameras, I typically use 64 GB cards, which are sufficient for now. But when doing video work, panoramas, timelapses, or doing lots of focus stacking, 64 GB is insufficient – a 128 GB or larger capacity cards are preferable.

Keep in mind that requirements for memory cards will change overtime. With the increase of resolution and bit depth in cameras, you might need to start moving up to larger capacity memory cards in the future.

6. Get a Fast and Reliable Memory Card Reader

Over the years, I have used many different memory card readers from Lexar, SanDisk and other third party manufacturers. I have never managed to damage a memory card because of a bad memory card reader, but it can happen.

As long as the memory card reader is not a really bad knock-off, it should generally do just fine. Most SD card readers built into laptops have the same OEM chips you will find on many other standalone memory card readers. So for the most part, the underlying technology is very similar in the majority of memory card readers. I personally really like Lexar and Sony-branded card readers, but there are some other ones out there that also work just as well.

For many years, my favorite card reader has been the Lexar Professional Workflow, which is an excellent card reader due to its versatility. However, ever since Lexar was sold to a Chinese company, I have not seen any real updates and new modules to support XQD or CFexpress cards.

For SD cards, the much simpler and smaller Lexar Professional USB 3.0 Dual-Slot Reader is also superb and works very well for both laptop and desktop use. I usually take the latter when I travel with my laptop, since it does not have an SD card reader. But if your laptop already has an SD card reader, then you don’t need to get an external unit, unless your memory card reader is very old and it cannot support fast transfer speeds of the latest memory cards.

7. Properly Format Memory Cards

When using memory cards, it is always a good practice to format those memory cards in your camera, and preferably, the camera brand you are going to be shooting with. While it is not necessary to format memory cards in cameras and you could go through the same process on your computer, I find it simpler and faster to do it in camera. When shooting with my Nikon DSLRs, all it takes to format a memory card is holding two buttons with red labels on the camera, then confirming the process by pressing those two buttons again. I could format all cards from my memory card holder in a minute or two, which is very convenient.

The other reason why you might want to format memory cards in your camera, is because some camera brands like Sony create a small database / index of files on memory cards after formatting them, so if your memory card does not contain those files, the camera will complain that the database does not exist and it will attempt to create the file structure and the database before the memory card can be used. Instead of going through these hassles, I find it better to just format all the memory cards you have in the same camera you are planning to shoot with. This way, you just pop a new memory card in and you are ready to keep on shooting.

If you decide to format memory cards in your computer, make sure that you check the “Quick Format” option.

You do not want your computer to do a low-level format of your memory cards. In fact, performing a low-level format, where the computer will go through each memory block on your card and fill it with zeros is bad for the overall health of your memory card, especially if you do it often, since those are write operations and each memory cell on your memory card only has so many writes to it before it becomes unusable. Plus, low-level formatting takes forever to complete, and if you ever want to retrieve files in case of accidental formatting, you will never be able to do so.

When formatting memory cards in your camera or performing a Quick Format on your computer, the formatting process simply re-creates the index table that stores where files are physically located on the memory card, so existing files are simply written over when a write operation takes place. You don’t see those files on your camera or your computer, but they are still there. That’s why it is possible to restore images from a memory card, even if the card is formatted. It is important to note that memory cards under 32 GB are typically formatted with FAT32 file system as seen above, whereas cards with larger capacities will be formatted with exFAT file system, due to capacity and file size limitations. Keep this in mind when manually formatting cards on your computer.

Some people choose to move contents of memory cards instead of formatting them. That’s a perfectly fine practice and there is nothing wrong with doing that, but I personally stay away from delete and move operations on my memory cards. Reading contents of a memory card is always going to be faster than read + delete.

8. Don’t Rush Deleting Images From Your Camera

If you do not like an image, or if it comes out blurry, it is OK to delete that image, but don’t rush with the process – take your time to delete only the image you need to delete. On many cameras, if you don’t pay attention to prompts and go too fast, you could accidentally delete more than one image, which could be a problem if your earlier image was something you were happy with. I have had a case when I was shooting a wedding and I managed to delete more than what I needed to delete, just because I pressed buttons too fast. If you need to delete an image you are not happy with and you shoot something very important, just do it later, when you have the time. Or if you do not want to risk it, skip image deletion in your camera and do it during your image culling process.

9. Keep Camera Batteries Charged!

Keeping your camera batteries charged is obviously a no-brainer. However, some of us are guilty of pushing cameras to their limits until batteries fully die. I never thought that a dead battery could cause a memory card to fail completely until I experienced it in the field. My camera battery died while recording a video, and after I popped a new battery in, I saw the dreaded “ERR” message. I knew something was going on with the memory card, so I took it out of the camera, put it on my computer and it was not recognized!

The failed write operation completely killed the memory card to the level that I could not even format it anymore. Needless to say, I lost all the work prior to the failure, so it was not a pleasant experience. Ever since, I have been paying close attention to the battery level – the moment the camera flashes with a red battery sign in live view, I swap the batteries out. Better safe than sorry!

10. Safely Eject Memory Cards – Don’t Just Unplug Them

Another obvious mistake to avoid, is unplugging a memory card while any read or write operations are taking place. While a read operation might do no damage to the card, an interrupted write operation often causes memory card corruption, as it happened in the above-mentioned situation.

If you want to stop a long exposure, don’t just remove the memory card or worse, your camera battery! Powering off your camera should stop the long exposure and safely complete write operations, which is what you want. If something happens to your camera and it seems to be stuck, you always want to wait for the memory card light to turn off before deciding to do anything drastic, like removing camera batteries.

There have been cases with some cameras being incompatible with particular memory cards and write operations would take excessively long as a result. Some photographers were not patient enough to wait for the light to turn off and they would take the battery out, which often resulted in memory card corruption. If you take a picture and it takes over 5 seconds for the memory light to go off, you might want to stop using that memory card and replace it with a different one.

The same goes for unplugging memory cards from computers – you never want to just remove a card while data is being read from or written to the memory card (again, write operations are particularly evil). The best practice is to safely eject the memory card via your operating system before removing it, which can be easily done in both Windows and Mac operating systems.

11. Avoid Static Charges

If you are in a very dry environment and you wear clothes that gather a lot of static, you might want to avoid touching memory cards. While the exterior shell of most memory cards is made out of plastic, the pins that connect to devices are made from copper and other materials that conduct electricity. And since electrical components can easily get fried with a static charge, you want to avoid touching them. If I know that I might be carrying a static charge, I usually find a piece of metal, such as a doorknob, that I can use to discharge the built-up static before touching any electrical devices, including cameras and memory cards.

12. If a Memory Card Fails, Stop Shooting

Memory card failures are pretty random. Some failures are temporary, with your camera reporting an error but then allowing you to continue shooting, while other errors are permanent – when there is more serious damage to the memory card. If you ever see an error on your camera while shooting to a particular memory card, stop shooting! The last thing you want is make matters worse by adding more images to the card and potentially corrupting the card even more. The moment you see an error, replace the memory card with another one. If the error persists, it might not be related to the memory card. But if the error disappears, your card might be failing.

The best course of action in such situations is to insert your memory card into a memory card reader as soon as possible and try to copy all the files. If the files are not corrupted and you are able to successfully copy all the files, you need to know whether it was a temporary failure on your camera, or the start of a memory card failure. Once the transfer is done, perform a low-level format of the memory card on your computer. If formatting fails or you see errors during the process, it is time to either send the memory card to the manufacturer for a replacement, or if you are outside the warranty period, it is time to trash it. If the low-level format completes and you see no errors, then you should be safe to use it again – just monitor the card and if you ever see another error, it might be safer to get rid of it than to continue using it.

If you cannot retrieve files from a failed memory card, chances of being able to get those files back are very slim. You can try using recovery software to get the files back, but recovery typically only works on deleted files and formatted cards, not on failed cards. If the data on the memory card is extremely important, you might want to reach out to your local data recovery company and ask if they can help. Keep in mind that such companies often charge a lot of money to restore your data!

13. Keep Memory Cards Protected From Direct Sun and Moisture

If you want to prolong the life of your memory cards, always protect them from extreme weather conditions. Never leave out memory cards under direct sun – keep in mind that memory card shells are made out of plastic and plastic can easily melt when exposed to the sun. In addition, by leaving memory cards under direct sun, you might damage electrical components of the cards, which might cause them to fail. Another enemy of electronics is moisture and water containing minerals. While pure H2O is not harmful in any way, saltwater and drinking water with minerals can cause an electrical short, which will certainly cause the device to fail.

If you accidentally drop a memory card in water, always make sure to fully dry it out before attempting to read data from it. Make sure that the card is not just dry on the outside, but also fully dry inside its plastic cover.

My preferred way to keep my memory cards safe from damage is to always keep them in a protected case, as explained above.

14. Use Memory Cards as a Backup

As I have pointed out earlier, I always try to keep a backup of my images in at least two different locations. If all I have is a laptop with me, then the laptop becomes primary storage and the memory cards I have used become secondary storage. If I have a laptop and an external drive, then those two become primary and secondary, while my memory cards become tertiary storage. As soon as I fill up a memory card, I put it back into my memory card case backwards. This way, I know exactly which memory cards have been used and which ones remain for me to use.

I can only remember one case when I shot so much that I ran out of cards on a three week-long trip and only after making sure that both my laptop and my external drive contained all the images, I finally formatted the largest capacity memory card to use on that trip. Since then, I bought a few more cards, so that I don’t run into this issue again.

15. Replace Memory Cards Every Few Years

Some of us stash memory cards in large sizes, thinking that we could use them forever. With any storage type, it is not about the question of “if”, it is the question of “when”. Memory cards fail and the more you use them, the more likely they are to fail at some point of time. So make it a good practice to replace memory cards every so often. Maybe every 3-4 years, maybe sooner or later, depending on how often you shoot.

Also, keep in mind that newer memory cards are most likely going to be much faster and potentially even more reliable compared to the really old memory cards – just make sure to check their specifications before buying them. You do not want to use a newer generation memory card that might have compatibility issues with your older camera, or your memory card reader.

Memory Card Myths

The Myth of Leaving Space on Memory Card

Some people argue that a memory card should never be filled completely, that doing so will either make it slower or increase the potential of memory card failure. This is a big myth from people who don’t know what they are talking about. First of all, I have never seen a case of a memory card filling up to the level where there is zero space left. When shooting images, if the camera sees that an image will not be able to fully fit on a memory card, it simply stops shooting and shows a “full” note. So the chances of fully taking up space on a memory card are very slim.

Second, memory cards don’t work like other types of storage that might slow down when there is little space left. Third, filling up a memory card does not increase chances of its failure. I have been shooting with digital cameras for over 10 years now and I never had to worry about stopping shooting when the number of frames left is low. I always shoot until my cameras tell me that the memory card is full. Even when shooting video, I have managed to fill up cards and yet I have never seen a card fail as a result.

The Myth of Deleting Images from Memory Cards

Another myth is that deleting images from your camera can cause problems with corruption and potential memory card failure. Again, I am not sure where such claims come from, but they have no scientific backing to them. There is no harm in deleting images from your camera, just like there is no harm in deleting images on your computer. I have been doing this for years and I have never seen a card fail because of it! If I shoot a blurry or a badly exposed image, I get rid of it as soon as I see it on the LCD. Why go through the hassle of culling and potentially importing unwanted images? There is no reason at all – feel free to delete images on your camera or on your computer and stop worrying about any potential harm.

The only case where you might want to avoid deleting images is when you have two memory cards setup in overflow mode. As I have pointed out earlier, your camera will place images in the first memory card that has available space, so if you keep on deleting images from one card after the camera already started putting images on another, you might create a mess. Also, if you do decide to delete images from your camera, make sure that you take your time and only delete what you need – some cameras are designed to continue asking if you want to delete images and if you are not careful, you might also accidentally delete previous images.

Memory Card FAQ

We compiled a list of frequently asked questions (FAQs) related to memory cards below:

It depends on many factors, including memory card quality, how often it is used and how it is cared for. Most memory cards can last 5 or more years, but it is recommended to replace them every few years, especially when they are used heavily.

When going through a standard formatting procedure on a computer (quick format), or on a digital camera, the index table that contains information about saved files is replaced with a new one. This means that if recovery software is used, the files should be recoverable, as long as no other data was written after the formatting took place. If new data is written after formatting, the data might still be recoverable, but only partially.

No, all memory cards come pre-formatted from factory. However, once they are used, it is recommended to format them through the camera.

Formatting a memory card removes all data, while deleting files only removes chosen files from the card.

That depends on many factors, including what memory card you need, what type of memory cards your camera supports, etc. Please see the article for our top recommended memory cards.

It depends on your needs. If you are starting out, we recommend buying at least two medium to high capacity memory cards, as explained in the article.

It depends on the memory card type, standard and its generation. The newest memory card standards allow memory card capacities up to 128 TB. In practice, the highest memory card capacities we see today range between 256 GB and 1 TB.

That depends on the size of pictures and compression type used. High resolution cameras can produce very large files, especially when they are in RAW format. Most cameras automatically approximate total number of images that can fit into a memory card, depending on what settings were chosen. To roughly calculate total number of images, divide the total memory card capacity by the typical size of images. For example, for an average size of 50 MB per RAW image, a 64 GB memory card will be able to hold roughly 1310 images (64*1024/50).

Memory Card Recommendations

Below are my top choices for memory cards:

- SD Cards: If your camera is limited to UHS-I interface, then go for the SanDisk 64 GB Extreme Pro UHS-I SDXC Memory Card. It is perhaps the best UHS-I memory card available on the market today thanks to its reliability, maximum read speed of 170 MB/sec, write speed of 90 MB/sec and a reasonable price. If your camera supports fast UHS-II memory cards, the big step up is the SanDisk 64 GB Extreme Pro UHS-II SDXC Memory Card, which can read up to 300 MB/sec and write up to 260 MB/sec speeds.

- microSD Cards: The microSD card I would recommend at the moment is SanDisk 64 GB Extreme Plus UHS-I microSDXC card – it should be fast enough for any device at the moment, including drones.

- XQD Cards: I personally use the Sony 64 GB XQD G-Series Card, but Delkin also makes a 64 GB XQD card that is similarly priced. If I wanted something with a larger capacity, I would personally go with the 120 GB version of the Sony card.

- CFexpress Cards: At the moment, I can recommend the Sony 128 GB CFexpress Type B Tough memory card, in addition to the SanDisk 128GB Extreme PRO CFexpress Card Type B card.

If you want to recover images from a memory card and don’t know how, our guide on How to Recover Deleted Photos from Memory Cards might help you out. Also, check out our detailed guide on Identifying and Testing Fake Memory Cards.

I hope you found this article useful. If you have any questions or feedback, please let me know in the comments section below.

I think it’s really weird to have a Photography Life comments section that does not allow users to post photographs.

What’s up with that? In my opinion, we need to be able to post photos to discuss them.

What do you guys think about this?

Best Regards

Arthur

How does one determine the amount of free storage space on a memory card in an Olympus E-M10, please? I’m unable find directions for this in the Olympus E-M10_Mark_IV_MANUAL_EN or via Google.

Thanks in advance, Arthur

What a silly question, Arthur.

The remaining number of images is usually displayed at the bottom right of the LCD once you’ve hit “info” to show your shooting information. You can double check this by seeing what number goes down as you take more photos. I don’t own the E-M10 specifically, though, and neither does the author of this article, so it may be best to reach out to an owner of the camera if this doesn’t answer your question.

Thanks Spencer.

I see two rows of text in the lower right corner of the Olympus E-M10 Mark IV screen. The top one looks like a time, in hh:mm:ss, and the bottom one appears to be a 4 digit number. Right now my camera displays:

2:35:06

9999

Perhaps the bottom one is given as (in pseudo Python)

max(10,000 – 1, remaining_space / average_size_of_stored_photos), # where

remaining_space = # the remaining space on the memory card, and

average_size_of_stored_photos = # total space used by stored photos / number stored photos,

where by “photo” I mean any photograph or video stored on the camera.

BTW, I think it’s really weird to have a Photography Life comments section that does not allow users to post photographs.

What’s up with that? In my opinion, we need to be able to post photos to discuss them.

Have any of you thought about this?

BR, Arthur

Hi

I have been told that memory cards have one or two chips that are class 10 and the other chips are a lower class. Would this be a fake card?

Nasim has done insane job here! Thumbs up! That said, author does get some things wrong.

Most notably this …

You do not want your computer to do a low-level format of your memory cards. In fact, performing a low-level format, where the computer will go through each memory block on your card and fill it with zeros is bad for the overall health of your memory card, especially if you do it often, since those are write operations and each memory cell on your memory card only has so many writes to it before it becomes unusable.

That’s not correct!!! In fact when you do not perform low-level formats every now and then you will wear out your card faster.

To understand this, one must understand how memory cards work. Put shortly, memory cards get “dirty” and fragmented over time.

Because how NAND flash works, you can not delete individual bytes from the card. You can erase data only at a block level. In layman’s terms, it means you have to delete multiple bytes simultaneously. One page of NAND Flash memory has 2,048 bytes and there are 64 pages per 1 block. So, you can only delete 64×2,048 byte size “lots” on the card.

Every now and then we all delete something from the card. And that leads me to the second mistake author made here. By saying that it is OK to delete data from the card, he was misleading.

Deleting files creates holes in the data. In order to free those holes and in order for the camera to be able to use that space, it must be deleted. However, if the photo you deleted did not take up the whole block, your memory card starts reallocating deleted data to pile it up on the one block. Once that block is filled, data can be deleted by the flash controller. That process is called “garbage collection.”

Shortly, the card will start to copy-paste data already on card. This forced data reallocation puts the card needlessly through extra write cycles and wears out the card faster. A lot faster.

If you quick format the card. That does not solve the problem, as quick format only clears the FAT (file allocation table), meaning the deleted (broken) bytes are still on the card and card must still go through the garbage collection process in order to write something on those deleted spots.

Moreover, it slows down the card, especially when it needs to copy-paste and move around existing information while the new data is pouring in.

Want to know more? Read the article by the experts here: progradedigital.com/how-t…mory-card/

Thank you, this was a very helpful article.

What does it mean when it says incript or excript

So informative!!

I left my sd memory card in my car – not sure how long it was in there but weeks for sure. I has been super hot and humid this summer. Will the heat and humidity effect my card?

Thank you

If securely seated is there any way a SD card can inadvertently dislodge while in cell phone for over a month?

Or would this require being tampered with?

Thank you

Hi, I have a doubt. If UHS-I has a bus limit of 104 MB/s, how could a Sandisk Extreme Plus/Pro SD card get those theoretical 160/170 MB/s?

Thanks!