An ultra-wide angle lens produces images with extremely wide angle of view. It is a popular choice among architecture and landscape photographers, because it can fit much of the foreground, as well as the surrounding elements in the photo.

Some of the ultra-wide angle lenses are of fisheye type, while others are rectilinear. In this article, we will go through both types and explain their differences.

Table of Contents

What is an Ultra-Wide Angle Lens?

An ultra-wide angle lens is a lens that covers focal lengths shorter than 24mm in full-frame equivalent field of view. This includes both prime lenses, as well as zoom lenses.

NIKON D750 + 15-30mm f/2.8 @ 15mm, ISO 200, 5 sec, f/16.0

For zoom lenses, if the wide-end of the focal range is below 24mm, it is considered to be an ultra-wide angle lens, even if its long end includes or exceeds 24mm. For example, both Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8G, as well as Nikon 16-35mm f/4G VR are ultra-wide angle lenses when mounted on a full-frame camera.

It is important to note that for a lens to be designated as an ultra-wide angle, both focal length and sensor size have to be taken into account.

NIKON D800E + Tamron SP 15-30mm f/2.8 Di VC USD @ 15mm, ISO 100, 1/40, f/9.0

This means that while a 20mm f/1.8 prime lens would be considered ultra-wide angle lens on a full-frame camera, it would no longer be considered as such on an APS-C sensor. This is due to 1.5x sensor cropping (also known as crop factor) that changes the field of view to roughly 30mm in full-frame equivalent. A similar 20mm lens mounted on a 1” sensor would fall into the “standard” range, with its equivalent FF field of view of 54mm.

Sensor Size vs Focal Length

Below is a table of different sensor sizes and focal lengths for ultra-wide angle lens designation:

- iPhone with 1/2.9” sensor (7.1x Crop Factor): Shorter than 3.4mm

- Smartphone with 1/2.3” sensor (5.62x Crop Factor): Shorter than 4.3mm

- 1” Sensor (2.7x Crop Factor): Shorter than 9mm

- Micro Four Thirds (2.0x Crop Factor): Shorter than 12mm

- APS-C (1.5x Crop Factor): Shorter than 16mm

- Full-Frame (1.0x Crop Factor): Shorter than 24mm

- Medium Format (0.78x Crop Factor): Shorter than 31mm

Fujifilm X-T2 + XF10-24mmF4 R OIS @ 10.5mm, ISO 200, 1/10, f/7.1

Who are Ultra-Wide Angle Lenses For?

Ultra-wide angle lenses are used by many different types of photographers, but they are arguably most popular among architecture and landscape photographers.

Architecture photographers use ultra-wide angle lenses to fit tall buildings into their frame. Real-estate photographers, in particular, often use ultra-wide angle lenses to photograph the interior.

Fujifilm X-H1 + XF10-24mmF4 R OIS @ 10mm, ISO 800, 1/15, f/5.6

Landscape photographers on the other hand, use ultra-wide angle lenses to exaggerate the relative size of foreground objects, while including vast landscapes in the background.

Fujifilm X-T2 + XF10-24mmF4 R OIS @ 15.9mm, ISO 200, 1/2, f/11.0

Other types of photographers also occasionally rely on ultra-wide angle lenses. For example, portrait photographers utilize ultra-wide angle lenses for photographing people in tight spaces, shooting environmental portraits and photographing very large groups of people.

NIKON D750 + 20mm f/1.8 @ ISO 200, 1/60, f/5.6

How Ultra-Wide Angle Lenses Affect Depth of Field

In photography, depth of field is affected by a number of different variables such as aperture, focal length, camera to subject distance and sensor size. And without a doubt, focal length is one of the biggest factors that influences the size of depth of field.

An ultra-wide angle lens has an extremely short focal length, which results in large depth of field, even when using relatively large apertures. Since ultra-wide angle lenses can reach infinity focus at close distances, they are often preferable when wanting to make both foreground and background appear sharp in images.

NIKON D750 + 20mm f/1.8 @ 20mm, ISO 720, 1/40, f/5.6

In addition, one does not have to deal with diffraction issues related to using very small apertures. Once hyperfocal distance is established and focused on, even larger apertures like f/4 can make the whole scene appear sharp from front to back at moderate camera-to-subject distances when using ultra-wide angle lenses.

Camera Shake Implications

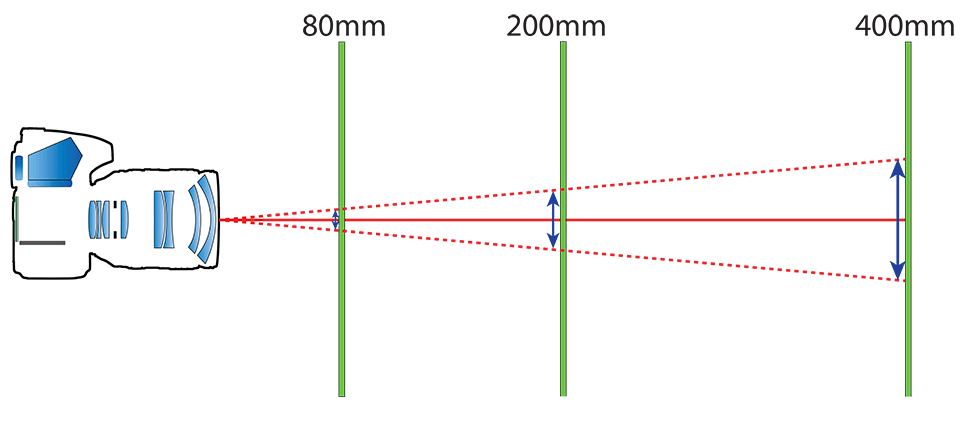

Since reciprocal rule is highly dependent on focal length, using ultra-wide angle lenses allow photographers to capture images at much slower shutter speeds. Take a look at the illustration below:

We can clearly see that shorter focal lengths reduce the potential for camera shake. Since ultra-wide angle lenses are so wide in field of view, the effect of camera shake is going to be least pronounced compared to lenses with longer focal lengths.

Fisheye vs Rectilinear Lenses

Ultra-wide angle lenses can be categorized into two different groups – fisheye and rectilinear.

Fisheye Lenses

Fisheye lenses are known for their curvilinear barrel distortion, which makes the image appear very distorted and straight lines can also appear curved.

NIKON D7000 + 10.5mm f/2.8 @ 10.5mm, ISO 100, 1/160, f/11.0

Many fisheye lenses are designed to capture extremely wide field of view that often exceeds 180 degrees. Images from circular fisheye lenses literally look circular, as shown below:

NIKON D810 + 8-15mm f/3.5-4.5 @ 8mm, ISO 64, 1/80, f/11.0

Rectilinear Lenses

Rectilinear lenses, on the other hand, are designed to make straight lines appear straight in the resulting images, as illustrated below:

Rectilinear lenses are designed to correct extreme barrel distortion, so they are typically more complex in their design compared to fisheye lenses.

Distortion from curvilinear lenses can be corrected in post-processing, with some loss of resolution and tighter framing. To avoid these issues, architectural photographers often choose rectilinear lenses instead of their fisheye counterparts.

It is important to note that focal length does not denote whether a lens is curvilinear or rectilinear. However, optically correcting for barrel distortion gets more difficult with shorter focal lengths. This is why lenses with extremely wide angle of view such as the Nikon 8-15mm f/3.5-4.5E ED (see NikonUSA product page) are typically of fisheye, curvilinear type.

NIKON D810 + Laowa 12mm f/2.8 @ 12mm, ISO 64, 1/60, f/16.0

Some lens manufacturers like Venus Optics specialize on rectilinear lenses. For example, the Laowa 12mm f/2.8 Zero-D has “zero distortion” in its name, so it is designed to be rectilinear, despite having such a wide angle of view of 12mm on full-frame cameras.

Filter Use

While ultra-wide angle lenses have many benefits, one of their biggest drawbacks has to do with the use of lens filters. Due to the fact that most ultra-wide angle lenses have big, bulbous front elements and built-in petal-shaped hoods, it is impossible to use standard filters such as ND and polarizing filter.

The solution is to use third party attachments and large filters, which can be expensive, time consuming to set up and bulky to travel with.

Some lens manufacturers have been able to design lenses with less bulky front filters and built-in filter threads. However, such designs are often rare, costly and might require a lens mount with very short flange distance.

For example, the Nikon Z 14-30mm f/4 S is an ultra-wide angle lens that accepts 82mm filters, making it possible to use it with polarizing, ND and other filters. However, this lens was specifically designed for the Nikon Z mount, which has a flange distance of 16mm – the shortest among all camera systems.

It is important to note that one has to be careful when using polarizing filters with ultra-wide angle lenses. Since the sky takes up a large portion of the frame, a polarizing filter can make the sky appear very uneven, as shown in the below image:

NIKON D810 + 20mm f/1.8 @ 20mm, ISO 100, 1/10, f/11.0

How to Use Ultra-Wide Angle Lenses

One of the biggest mistakes many beginner photographers make when using ultra-wide angle lenses, is compose images like they do with their normal lenses. This often results in a lot of negative space, with too much sky and empty foreground. The main subject of the scene, as well as its surroundings in the distance end up looking insignificant, because ultra-wide angle lenses make them look very small.

NIKON Z 7 + Laowa 10-18mm f/4.5-5.6 @ 10mm, ISO 160, 1/100, f/8

So how does one get around this problem? Since ultra-wide angle lenses exaggerate the size of foreground objects relative to the background, they are best used at close proximity to the primary subject. The point is to highlight the subject, making it appear proportionally larger than its surroundings or the background.

NIKON Z 7 + Laowa 10-18mm f/4.5-5.6 @ 10mm, ISO 200, 1/40, f/11

This makes ultra-wide angle lenses quite powerful, as photographers can choose a small subject like a rock or a flower, and make it look much larger than everything else in the scene.

Fujifilm X-H1 + XF10-24mmF4 R OIS @ 14.5mm, ISO 200, 1/45, f/8.0

In order to reduce the amount of space taken up by the sky, one can tilt the camera down, which highlights the foreground area even more (note that I intentionally did this in many of the images presented in this article).

Frequently Asked Questions

Below is a small collection of frequently-asked questions related to ultra-wide angle lenses.

An ultra-wide angle lens can be used for many different types of photography, such as architecture, landscape and environmental portraiture.

The number of ultra-wide angle lenses available today for different systems is quite vast, so it is impossible to pin-point the single best lens. Also, there are several types of ultra-wide angle lenses, with different optical designs and focal lengths. Here are some of our top recommended ultra-wide angle lenses for different camera systems:

Nikon F: 14-24mm f/2.8G and 16-35mm f/4G ED VR

Nikon Z: Z 14-30mm f/4 S

Canon EF: EF 11-24mm f/4L USM and EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM

Sony FE: FE 12-24mm f/4 G and FE 16-35mm f/2.8 GM

Fujifilm X: XF 8-16mm f/2.8 R LM WR and XF 10-24mm f/4 R OIS

Yes, ultra-wide angle lenses are particularly good for astrophotography. Such lenses as the Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8G and Nikon 20mm f/1.8G are often used by astrophotographers to photograph the night sky. Here is an example of a photograph of the Milky Way, captured with the Nikon 20mm f/1.8G lens:

Designing and manufacturing ultra-wide angle lenses is not easy. Many high-performance ultra-wide angle lenses have complex optical designs that utilize aspherical lens elements, which are expensive to make.

Nasin,

I write, not just to show my appreciation for this article, but for your ultra-perfect photo of the bride in the room. I have and use the 20mm F/1.8 lens. It is not just the sharpness, it is the perfect lines without any bowing. Knowing your ability, you probably hand-held the camera. Wonderful image. Great website. Never buy anything without consulting your articles first.

Regards,

peter

I have owned and used a Tokina 11-16mm f2.8 lens on my Nikon APS -C camera for years. It is a ultra wide angle lens for apps-c cameras and has proven to be an excellent lens for me and my style of shooting. This lens can often be found used at very low prices and the image quality is surprisingly excellent. It can be hard to find good ultra wide angle lenses for apps-c. No image stabilizer but as this article shows that this is not really necessary for an ultra wide angle lens. This is a very sturdy well built lens with the only oddity being the manual/auto focus push pull clutch that Tokina uses but once you try it you may find, as I do, that it works quite well. I have owned my lens for about 6 years and it has proven to be a very capable lens. Very accurate and well written article.

Nasim, thank you for a very informative article. My colleagues presented me with a Zeiss Batis 18mm f/2.8 as a retirement gift this past January. This article explains (and hopefully remedies) a lot of the difficulties I am having with this beautiful piece of gear. Thanks again.

Paul, that’s a pretty amazing gift you got there, congratulations! I have used Zeiss Batis lenses in the past – they are truly superb!

Nasim, thanks. I just retired from a wonderful career of 34 years as an anesthesiologist. I was fortunate to be surrounded by great colleagues. Now I have a lot of time to figure out the lens.

Nasim,

Nice article.

I love my wide lenses, especially my new (to me) Venus LAOWA 9/2.8 for Fujifilm X mount (APS-C, of course). It may not have *zero* distortion, but it is pretty good, except for a bit too much vignetting. Small, affordable, very good build, and threaded for 49 mm filters! I like it for tight city streets and woodlands, as I’m less fond of ultrawide in more open settings. To me, 16 mm on APS-C does not feel ultra, just wide…similarly, back when I shot on 24×36, i thought my longest ultrawide was 20 mm, not 24. But that’s as much personal vision and use as objective, I reckon.

To me, it is simpler just to know the sensor diagonal. Then anything less is wide, less than ½ the diagonal is ultrawide. So, for APS-C, ~28 and 14 mm, resp. Easy!

Thanks again.

Chris

Chris, thank you for your feedback, I really appreciate it!

I haven’t tried the Laowa 9mm f/2.8 yet, but it sounds like a fun lens to use on a Fuji X camera! I think all ultra-wide angle lenses suffer from vignetting – the wider the lens, the more obvious it is.

As for what defines an “ultra-wide” vs “wide”, I think the common way is to use the height of the sensor as the limit, which for a full-frame camera is 24mm. However, as you noted, it is a subjective matter – for some people 24mm is not wide enough to qualify as “ultra-wide”…

Hi Nasim,

In several places you refer to focal lengths wider than 24mm. Wouldn’t you mean shorter than 24mm? I don’t mean to be picky, but it reads a little odd. If I am wrong, mea culpa. :)

Eliane, I think what Nasim is talking about is the field-of-view which is wider the smaller the focal length is (so e.g. 15mm begin “wider” than 24mm). It is a common terminology when talking about lenses.

Martin, I understood it perfectly just the way it was. It’s just that it is inconsistent with the way the rest of the article is written, and may have been an oversight due to familiarity with the shorthand that experienced photographers use. It could easily confuse beginners, so I thought I’d point it out, and Nasim could change it if he so chose. All I meant was that to talk of a lens as wider at one end and longer at the other, or a longer lens does this and a wider lens does that, reads a little oddly.

Hi Eliane, ok, I see. Your input makes sense to me now.

Elaine, I agree – I think it is better to use “shorter than” instead of “wider than” for beginners. I changed the references in the article, thanks for your input!