There’s no real upper limit to how large a camera sensor or film can be. Full frame cameras are smaller than medium format digital, which itself falls behind most medium format film – and so on. At the high end of the scale are Ultra-Large Format (ULF) film cameras.

What is an ultra-large format camera? It’s any camera with an imaging area larger than 8×10 inches. In other words, each individual sheet of film – and it is film rather than digital, unless you’re NASA – is substantially larger than a standard sheet of printer paper. Even a basic 1200 PPI scan of ultra-large format film is going to be hundreds of megapixels… not that most scanners can fit such large sheets of film in the first place.

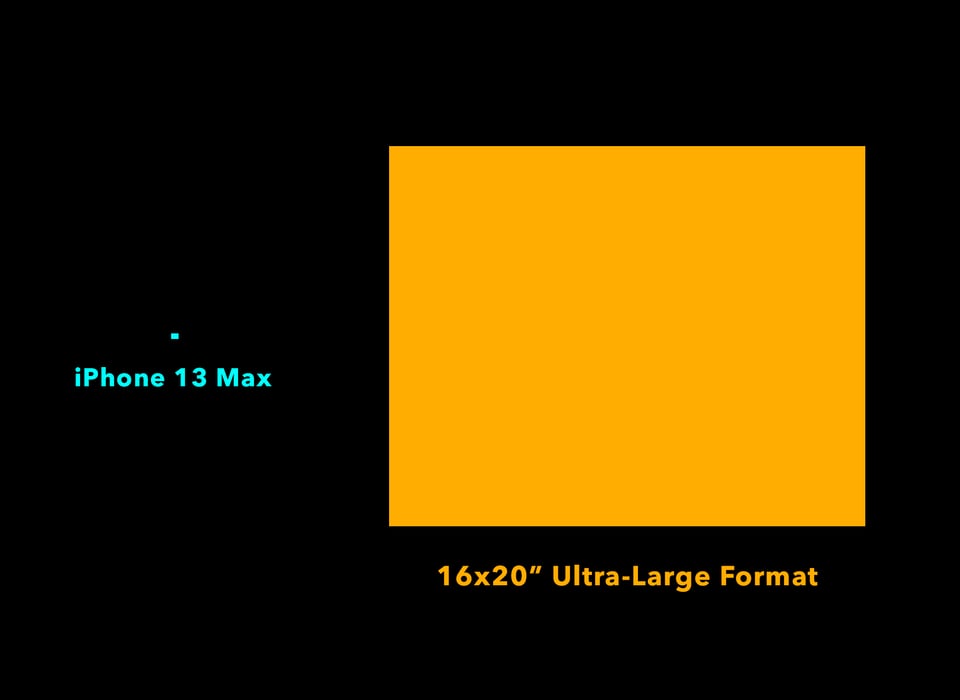

As the name implies, ultra-large format is massive compared to typical 35mm full-frame sensors or even medium format. Relative to the sensors in a phone, the difference is astronomical.

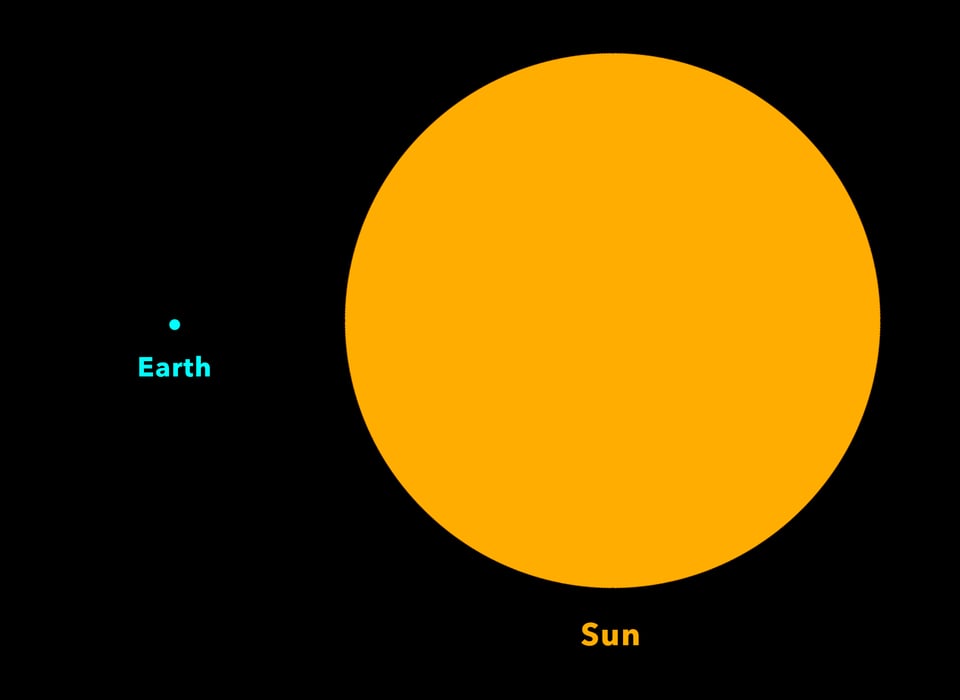

I chose that term – “astronomical” – because comparisons to astronomy are easy to make with cameras this large. For example, here’s the relative size of the Earth versus the Sun:

And here’s the largest sensor on the iPhone 13 Pro Max versus ultra-large format film (16×20, not even the largest standard ULF size):

Many digital photographers have at least heard of 4×5 or 8×10 film cameras, which are large cameras in their own right. But those aren’t ultra-large format. They’re not big enough. Instead, the usual classification goes like this:

- Typical digital cameras through 6×9 cm film: Medium format and smaller

- 4×5 through 8×10 inch film: Large format

- Anything larger: Ultra-large format (ULF)

These days, the most popular formats of ULF cameras are 11×14, 14×17, 16×20, and 20×24. There are also more panoramic sizes like 7×17, 8×20, and 12×20. (All of those dimensions are the inch measurements of the film for the camera; by comparison, a full-frame sensor is about 1×1.5 inches.)

For many ULF photographers, shooting with this sort of camera is a hobby in and of itself. Think of the differences between off-road Jeepers, vintage car restorationists, and minivan parents. All of them can technically get you from Point A to Point B, but they’re not really after the same things. That said, these cameras all involve photography at the end of the day, and you can get some stunning images from ULF cameras with enough effort.

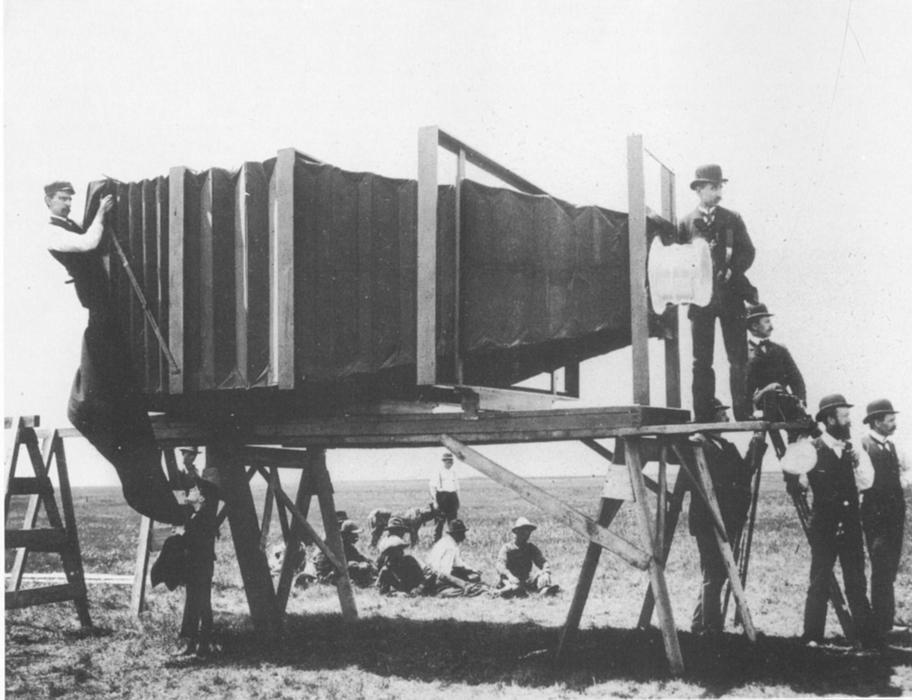

Here’s what a particularly big ultra-large format camera looks like:

This one, admittedly, is a bit extreme. It’s a 4.5×8 foot camera that was the largest camera in the world in the early 1900s. No surprise, that’s large enough that you’d have to build one from scratch today rather than buying from an established company. But it goes to show that these cameras can be as big as you can build them.

If you’re wondering, there are some working professional photographers who use ultra-large format cameras today (generally not quite 4.5×8 feet) and even a few companies that still make them new. So, I want to push back on the idea that ultra-large format cameras are nothing but antiquated collectibles. Nor are they just “let’s test my woodworking skills” builds. Here and there, a few photographers still put in the extraordinary effort required to use these cameras because the results can be impossible to achieve any other way.

And what results are those? For most photographers, it’s all about contact printing – placing the negative directly on a sheet of light-sensitive paper and getting a one-to-one print. Contact prints are remarkably faithful to the original negative (if you want them to be) and are capable of more detail than just about any other type of print. However, it’s an all-analog process with a lot of hoops to jump through before it turns out right.

Challenges of Ultra-Large Format Cameras

I know that by writing about ultra-large format cameras on a popular site like Photography Life, I may be tempting some photographers who never even knew such cameras existed to get that twinkle of GAS in their eyes. But to most photographers, I urge against buying one. They’re remarkable cameras, but they’re also impractical in almost every way.

If you’re feeling adventurous, there’s a better solution: Go for a large format 4×5 or 8×10 camera instead. Those formats are already slow and difficult to use – easily enough to fill your daily quota of tribulation. But at least they’re nearly reasonable. With 4×5 or 8×10 cameras, you have a good selection of lenses, film, spare parts, and accessories, and you should be able to troubleshoot any problems pretty easily. By comparison, the ultra-large format realm is like pulling teeth from a chicken while simultaneously herding cats.

An unavoidable fact of ultra-large format cameras is that they are large and heavy. Take the smaller end of things, for example: 11×14. Typical 11×14 cameras weigh about 20 pounds, not counting at least an additional 3-5 pounds of weight for a lens and a two-shot film holder. Even the lightest 11×14 cameras on the market (aside from rare custom builds) weigh about 13 or 14 pounds, body only.

If you plan to carry such a camera beyond view of your car, good luck finding a backpack that can hold it comfortably – or even fit the camera in the first place. I’ve seen some photographers repurpose cumbersome kayaking backpacks for the job because at least those bags are big enough. Other photographers, even today, carry these cameras on a horse or mule.

What ultra-large format lacks in practicality, it makes up for by being fiendishly expensive. Some “alternative” films aren’t so bad – like repurposing x-ray film from the medical industry – but a single 11×14 sheet of a standard B&W film like Ilford FP4+ is about $12. The cost of developing the negative is another few dollars for the chemicals if you do it at home, or $10 at one of the few remaining labs which still develops 11×14. That’s $15-20 per photo! It better be good. (Color film at this size does exist, but only via special order from Kodak or an intermediary, and the minimum order costs about as much as a new car.)

For crying out loud, the Wikipedia page on ultra-large format photography has a dedicated section called “encumbrances.” Beware, beware, when ULF is in the air.

Why I Got One Anyway

How could I resist something like that? Meet my 12×20:

I’ve been saving for this camera since I first learned about ultra-large format photography several years ago, and it arrived not long ago. Yes, it’s difficult to use (to put it mildly) and yes, digital cameras have a million advantages over it. But for a number of reasons, I love using this for my landscape photography.

The biggest benefit for me is the experimentation of doing large contact prints in the darkroom, but it’s also true that – if everything goes right – the amount of detail possible per shot with this camera is remarkable. A decent scan would reveal enough detail for wall-sized digital prints, should I feel inclined. (For now, I’m “scanning” the negatives for the web by simply putting them on a light table and photographing them with my digital camera, and I’m only printing analog.)

Cumbersome though the 12×20 format is, I’ve done as much as possible to keep my 12×20 setup backpackable. Because it’s a somewhat panoramic format, the camera just barely slides into my largest 95 liter hiking backpack along with one film holder – two if I stretch things. The camera weighs about 18 pounds on its own, and the whole backpack is about 40 once the tripod, lenses, film holder, and various accessories are added (though before anything like food or shelter). That’s light enough that I don’t mind carrying it a few miles for a photo.

It’s tricky to find lenses that cover such a large format. I have a set of five lenses from 270mm to 762mm, representing about 20mm to 56mm equivalent focal lengths on a full-frame digital camera. (You can see my full lens recommendations for 12×20 here.) Anything longer than 600mm is difficult to use due to camera shake issues. In fact, no matter what lens you use, the whole camera is basically unworkable if there’s more than a light breeze. The bellows act like a sail and make the camera pretty unstable.

The 12×20 isn’t my primary camera, of course. Instead, it acts as a complement to the 4×5 and 8×10 cameras that I’ve switched to for most of my landscape photography needs. You read that right – I’ve moved to large-format film for my dedicated landscape kit, although I’m still using digital for anything other than landscapes. The 12×20 camera is for special occasions when I have time to set everything up and really create the right shot.

I know that Photography Life has an almost exclusively digital audience, which is why I’ve avoided talking about my experiences with large- and ultra-large format film so far. But it’s become such an important part of my photography that I’ll surely write about it some in the future.

In the meantime, I’ll leave you with some sample photos from the large format film cameras I’ve taken over the past year. These are the sorts of landscapes that I’m planning to capture with my film kits from now on – assuming I spend enough time in the gym that I can carry the 12×20 beyond my car, that is.

Ha, ran into this from the tripod article…

Had ambition to do 4×5 in the ’70s, hung out with a few folk who contributed to Arizona Highways. At the time I could barely afford 35mm, so that was not to be.

A few years ago, I came into a 1903 Eastman 8×10:

Beautiful assemblage of wood, brass, and leather. Working full-time I couldn’t come up with the time to work with it, so I sold it. Recently, the owner gifted it back after encountering major health issues, it’s like a booger on my finger, can’t shake it off… :D

He had a 5×7 back for it, and I think that came with the gift. With retirement looming, I may yet have the time and resources to expose a couple of sheets…

Spencer, I’ve followed you in your PL articles, your attention to detail is without equal, and I’m sure it will serve you well wringing compelling images from these beasts. Keep posting about it, I think based on the previous comments enough of us will read with interest.

Thank you, Glenn! Wow, what a beautiful camera. There’s still a lot of good 8×10 film on the market. You should definitely shoot some sheets if you get the chance.

I was surprised by how many people were interested in this article. It seems film isn’t quite dead! I’m working on a few other large format articles and hoping to post them soon.

I am sorry, can’t help it…this reminds me of high school days in the late-60’s in Indianapolis when I got involved with the school newspaper and yearbook. Whoever designed the darkroom painted the walls black and ordered two Omega D2V enlargers with 4×5 negative carriers, along with 4×5 film holders and hard-rubber dip tanks, and boxes of Kodak Super-XX 4×5 film, DK-50 film developer, stop bath, fixer and hypo-clear; boxes of Kodak 8×10 and 5×7 glossy multigrade paper along with a set of filters to change the paper grade from 0 to 4, dodging and burning tools, a noisy drum dryer, and film-developing clock. Nobody had used this stuff, preferring their own 35mm cameras and Tri-X film (which we bulk-loaded from 100′ rolls via a Watson bulk-loader that the journalism dept. bought) and made it work in the 4×5 film holders. The camera the school board supplied was a 4×5 Speed Graphic with 135mm Wollensak lens and a set of 4×5 film holders, and a shoulder-holster that held a dozen of them. Also a big Graflex potato-masher flash with an automobile-sized battery on a shoulder strap. Talk about f/11 and forget it! I decided to teach myself how to use this stuff, and got a lot of great 8×10 prints with wonderful tonal range, courtesy of the 4×5 negative. I eventually gave up this cumbersome rig for a Minolta SRT-101 I bought at K-Mart, along with lenses and a Vivitar 283 flash from K-mart and Sears. I bulk-loaded the school’s Tri-X and shot for both the newspaper and yearbook in high school; and continued in college. Made out with girls in the darkroom. Those were the days.

That’s brilliant! Even the newest 4×5 cameras follow the same design inspiration as cameras from 100 years ago. It’s just the fundamentals: a light-proof box, a light-sensitive sheet, and light.

Great stories!

I once designed darkrooms and studios for a college where I was teaching and battled for ages with the college and the architects, trying to explain that the darkrooms should be painted white and the studios black.

Eventually, I managed to persuade them that the darkrooms should be white but failed miserably with the studios! They refused to paint then black and they ended up white! For the rest of my time there, I struggled with the white studios. They simply could not understand why a studio should be black!

I used to live near an Ilford factory in the U.K. Good to know the FP4 is still in demand. I remember using it my old Spotmatic. Lovely camera that …

Wistful sighs …

FP4 is going strong! I’m mainly using HP5+ 400 on the 12×20. Ilford is the biggest company that offers custom film sizes this large without a big minimum order. I’m a fan.

I have noticed the remarkable amount of detail that can be extracted from my grandad’s Kodak Vestpocket contact prints (127). All slow finegrain emuldions in those days… I now get occasional urges to dig out the ancestral 120 folder, but I don’t think I’m likely to be buying or carrying anything larger, any time soon!

I’d like to wish you well in your new endeavour. Do you think it will be possible to display a few images on line somewhere at a worthwhile size and quality?

At the same time, I selfishly hope that you will not be leaving the digital world completely! Your ability to demistify and explain would be a significant loss to many of us strugglers.

It is pretty incredible! Contact prints are something else. Displaying them online without losing something will be impossible, unfortunately. But I’m going to scan them at high resolution and publish those results here, so it will at least be a taste of how they look in person.

I’m still shooting a lot of digital. Especially for travel photography – just not realistic to shoot anything handheld or fast with the 4×5. And my pace of (digital) reviews is only going to speed up.

Thanks for your article, and I look forward to living vicariously through your adventures into film and the larger formats.

I found a Pentax 6×7 to F mount adapter with some basic shift & tilt capabilities (it can rotate to also give rise/fall & swing), and have picked up a few P67 lenses to try out.

I appreciate that it has nothing compared to the movements possible with your cameras, but I am enjoying them, when I get the chance.

I occasionally look at the prices of P67 bodies too, but that’s just wishful thinking.

All the best, and good luck with the lunges and squats training to carry all the gear 😁

Cheers,

I’m a big fan of that. At the end of the day, I’m not coming anywhere close to exhausting the movements on these cameras anyway as a landscape photographer. The P67 adapter should give you some great creative options.

Love that crater lake shot.

Thank you, Andy! I’m glad that one turned out. It was very windy when I took it, and I didn’t know if it was sharp until I got back the developed negative. Probably my favorite 4×5 shot so far.

An interesting discussion!

There is one other aspect that I think applies to large format photography, not just analogue either. As the film or sensor size increases, you get a subtle but absolutely tangible increase in the subtlety of tonal gradation.

For instance, when going from 35mm film to medium format or 5X4′ film, you see this quite clearly. You obviously get an increase in sharpness as the silver particles (B&W) or dye particles (colour) are proportionately smaller with the same degree of image size but it is the difference in subtlety of tone that is most striking to me. I think the same will be true for digital sensors as well, although I have no experience of MF or LF digital.

So, when viewing a print (or transparency) from a 5X4″ image, the sharpness increase is certainly very striking compared to smaller formats but the real hit (for me at least) is the subtlety of the tonal and colour gradation. Hard to describe, probably not very visible on web repro. but most definitely a major feature when viewed ‘in the flesh’.

I have many 5X4 transparencies, shot in studio of (for instance) watches that are truly startling when viewed through a good loupe on a light box. When printed at high resolution and quality in their final destination, they look wonderful. I have seen 8X10 transparencies shot by other photographers that were even more breath-taking to look at and looked even better when printed to high quality.

Totally agree…it’s all (slight exaggeration) about the additional subtlety of tones. ;-)

There are a couple of other things also playing a role. For instance, no matter how hard you try to “get the details right” in modelling (= building models) of planes, cars, railways in smaller scales than 1:1. There’s a moment when a fine, rusty or brushed surface simply doesn’t appear the same way, when upscaling a 1:72 model to 1:1, when you see sort of natural looking materials can’t be upscaled without becoming an obvious fake. The same way of upscaling a certain sensor size, you’re also upscaling it’s flaws. They simply become visible, quicker than large scale transparencies.

Next thing is the “ridden to death horse” equivalence. In theory it’s possible to downscale a lens for a smaller sensor. In practice, tolerances soon become very critcial. A church tower clock doesn’t need the tight tolerances of a wristwatch to work properly. And while downscaling of lenses, tubes, diaphragms is possible, dirt particles, water droplets don’t downscale and can do more severe damage on small structures. We need to bear in mind that the camera obscura first WAS a chamber with a hole in to draw a picture on a canvas or large sheet of paper. We have super miniaturized camera obscuras, but there’s no free lunch. Sometimes what you get in portability has to be paid with the loss of other qualities.

Congratulations, Spencer: 4×5 and 8×10 were my standard cameras for 30 years. I shot 4×5 hand held with Linhof and Graphics, 4×5 with Linhof view cameras, and 8×10 with Ansco and Kodak view cameras. I carried the 8×10 up rope ladders in Mesa Verde. Probably not allowed these days. Even shot a legislative session with a 10×20 once.

You already found out that the wind really starts to blow when the camera goes up on the tripod. Get a big focusing cloth and do a spread your wings to try to block the wind.

Old lenses are the way to go. I used brass barrel 8 1/4″ and 12″Goerz Dagors for b&w and the 300 Nikon-M for color on 8×10. The Dagor made images with a smoothness unseen with the Nikon. In addition, the rear element of the Dagor was a 23″ telephoto. That was the way in the old days-see AA “Moonrise Hernanez” made with the rear element of a Cooke convertible.

Commenter made a good point about the inaccurate leaf shutter speeds. The solution is an inexpensive Calumet digital shutter tester probably available on ebay. I calibrated my shutter frequently.

There is something about the traditional process and the unique way a a view camera can be made to change shapes that is undefinable. It needs to be experienced.

You have a distinct manner of articulating tests and reviews. Keep up the good work!

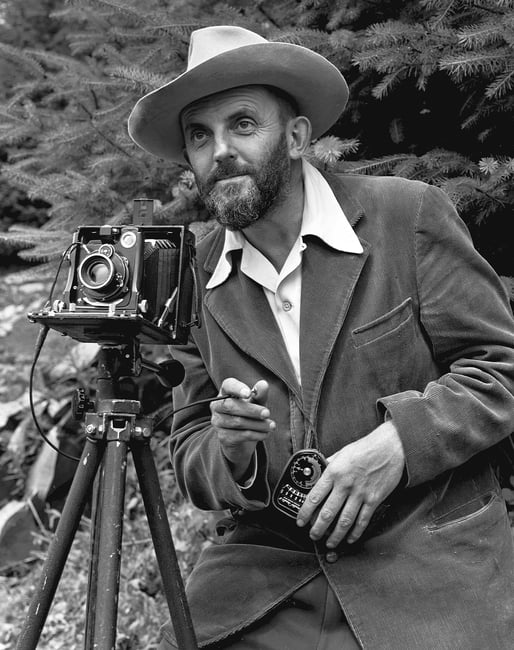

Spencer, I’m delighted to see you venturing into the wonderful world of large format! I still have my Toyo 4×5 and one (very fine) lens, and have been thinking of reactivating it. Seeing the huge enlargements of Ansel Adams and his contemporaries inspired me to crawl under the dark cloth–there’s nothing like either the experience or the results. I hope you continue to post articles on LF.

Thank you, Art! I’m sure I’ll post more about it in the future. Large format is such a fun process and leads to some great results if done with care.

I would stick with 4×5 and get a really good scan. Ive never even shot a 8×10 but I have seen the output. 12×20 is much bigger but is the resolution? I am curious to see the difference. Is it worth it? And can you really get color film that big? I have questions I can only get answers to if I see the output with my own eyes.

For the most part, that’s what I’m doing. The 4×5 (and 8×10) is by far my primary system. I’m scanning all the images I take with it and editing them in Lightroom. It’s actually similar to my digital workflow, just a bit slower.

I didn’t get the 12×20 for higher resolution (although that is nice in theory), but to make big contact prints using archival analog processes like pt/pd and carbon transfer.

Color film is technically available at 12×20 but only via an unreasonably expensive custom order from Kodak, which I haven’t done. I did find a pack of 20 expired Portra 160 negatives in 12×20, and I’m treating it like gold. I’ve only shot one so far and haven’t developed it because I’m trying to master my color development techniques first.