One of the most popular ways to compose your photographs is to use the “Rule of Thirds”. Although this compositional rule is frequently used by photographers, not everyone understands exactly what it is or when it works. This article introduces the rule of thirds and explains when to use it for composition (or not). Keep in mind that this rule is a suggestion for beginners and those who struggle with properly composing their pictures, and it is far from the only way to take good images.

NIKON D800E + 105mm f/2.8 @ 105mm, ISO 100, 1/640, f/3.2 © Spencer Cox

Table of Contents

What is the Rule of Thirds?

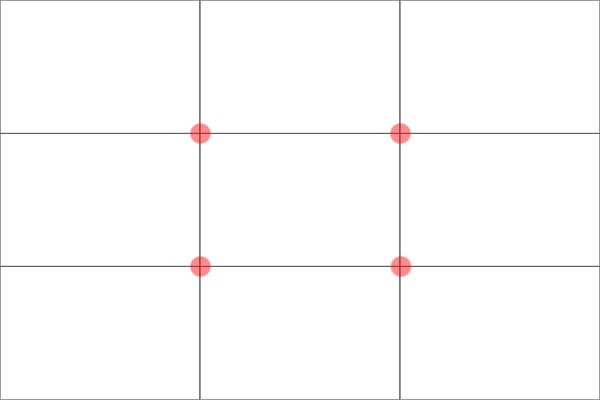

The Rule of Thirds is a type of off-center composition where important elements of a photograph are placed along a 3×3 grid, which equally divides the image into nine parts. For many photographers, this type of composition is a basic way to give structure to photographs and make them more appealing. With the rule of thirds, photographers envision four lines across their photographs, which also creates four intersecting points. Take a look at the illustration below:

The important elements within a frame should be placed at the intersection points of these lines, as shown in the above diagram. Or, when photographing subjects like a tree or horizon, which are comprised of straight lines, the rule of thirds suggests placing them along one of the four lines instead. Take a look at the below photograph:

As you can see, both the horizon line and the primary subject are placed along this grid:

You can apply the rule of thirds to any genre of photography. In the portrait example below, the subject’s eyes are placed about two thirds up the photograph, and her nose aligns with the rule of thirds grid as well:

How to Use the Rule of Thirds

To use the rule of thirds, start by imagining a 3×3 grid and place your subjects along those lines and intersections points. When you evaluate the result, you may find that you like it more than with your subject in the center.

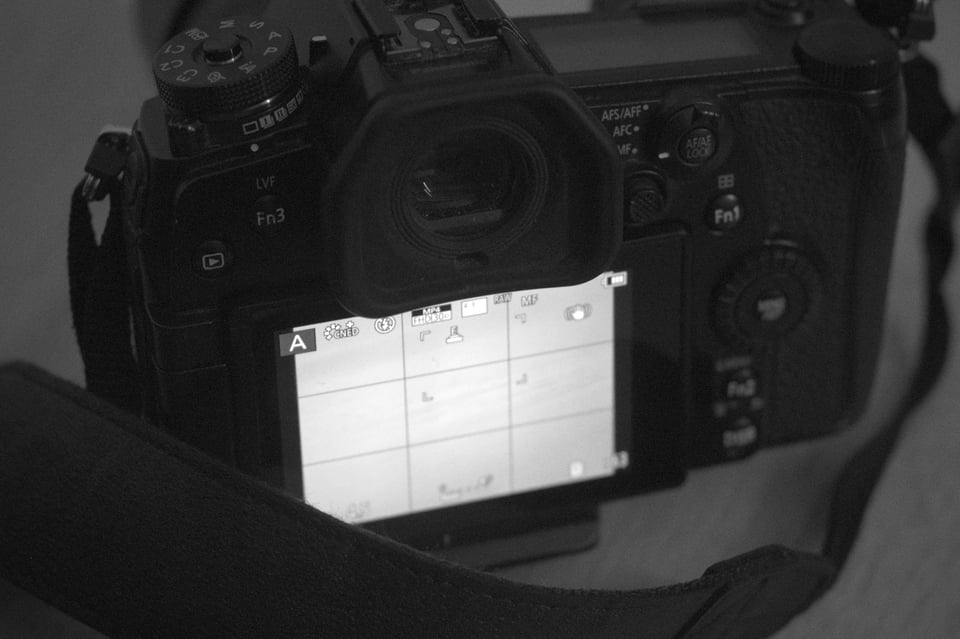

Some cameras also have a built-in guide for rule of thirds composition, which is shown as an overlay in the rear-view display or electronic viewfinder:

As a bonus, using these guides can help you straighten your horizon in landscape photography.

Finally, the rule of thirds isn’t only for composing while shooting. You can also use it for cropping photos in post. All modern Raw editors have an option to show thirds guides while you are cropping so you do not have to guess where the thirds lines are.

When to Use the Rule of Thirds

The rule of thirds works well when there is a strong point of interest in your photo, and you want to contrast that point of interest with the supporting elements in your scene. As an example, consider this shot:

In this shot, the attractive eye of the Egyptian Goose is placed roughly in the upper third of the photo, contrasting with the rest of the scene. Not only does this give the rest of the scene more room in the photo, it also places the bird in a more natural pose that shows most of its body.

In landscape photography, the horizon line is also frequently placed roughly on the thirds line:

This breaks the balance between the sky and the ground, and gives one more emphasis than the other. Even if you do plan on placing the horizon line outside of the basic thirds lines, starting with a rule of thirds composition in your viewfinder can be the first step to the perfect composition.

The rule of thirds works very well in more minimalist compositions, where the subject is concentrated in a relatively small area of the photo, and the rest of the photo is subdued, such as in photos of people with a blurred background:

So, when should you use the rule of thirds? The basic value of this rule is to remind yourself that off-center compositions can work well and be successful. Most of the time, beginner photographers will place their subjects in the dead center by default, forming central compositions. Although central composition can be a very strong way to compose photographs, using it for every photo can be boring. If you find that you are doing this, you can add more interest and variety by using the rule of thirds.

So, if you are struggling to compose your images, you might find that the rule of thirds can be a quick way to make your photos more dynamic.

When Not to Use the Rule of Thirds

The biggest problem with the rule of thirds is that it doesn’t change, even when your subjects do. It simply does not take into account what you are photographing. For example, in some scenes, you might be compromising your composition and excluding important elements just to adhere to the rule of thirds. So, in a way, it is a cookie-cutter composition.

The whole idea of the rule of thirds is that it introduces beginners to off-center composition. However, it might lead you to think that your subjects always (or often) need to be placed along the exact lines and intersections of the 3×3 grid in order to capture a successful composition.

In reality, any type of off-central composition – not just the rule of thirds – can work well. Instead, try framing your subject just slightly off center, or even in the extreme corners. Sometimes, the scene itself will dictate the type of composition which will work best for your photograph. In the image below, you can see that the subject has been placed close to the edge of the frame in order to convey a sense of isolation with a negative space composition:

While taking this photo, the goal was to make it look somewhat striking and unexpected. Had the photo followed the rule of thirds, it would not have conveyed that emotional message.

Along with that, do not underestimate central composition. Although it can be boring if you use it too much, it also can be the most powerful way to compose and frame photographs. For example, it works very well if there is a single, strong subject in the scene:

NIKON D800E + 70-200mm f/4 @ 200mm, ISO 100, 1/160, f/9.0 © Spencer Cox

The rule of thirds is a consequence of a more general theory of composition that the elements in your photo should work together to create a sense of balance between harmony and disharmony, that convey both the subject of your shot and your own emotions as a viewer of the scene. In some cases, and especially with simple compositions, the rule of thirds gets pretty close to that ideal. In other cases, you may need to try something else.

Conclusion

The rule of thirds is certainly worth exploring, especially for those who are just starting to learn composition in photography. However, as you get more advanced, you will start to realize that good composition is not about adhering to strict rules, but rather about composing each photo for its own merits. Different compositions will be ideal in different situations. While the rule of thirds works well for some photographs, it is not the only way to capture a good image. Indeed, any type of composition can be beautiful, and you will miss many opportunities if you never go beyond the rule of thirds.

Nice article! Stumbled upon this website by chance (even though I’m not a photographer) after watching a video about discerning AI-generated text, and the first thing I saw is the motto “AI-free since 2008”. Found the coincidence funny :) Nice attitude, too; useful info written by humans becomes more and more valuable every day, so thank you!

I would like to say that the outcome of the selected shot or scene is determined by the individual behind the lens. Evoking the same emotion and energy as said person. But there is an art to it and I am sure that the rule is applicable to most of said subject of discussion

Very interesting…

very the good

I have questions rather than a comment. I’m using Photoshop CC 2018 and need a better computer screen for more accuracy when editing. Can you suggest one? I have a Dell laptop which I love and thought I might be able to add another screen.

Also, could you recommend a medium to expensive price photo printer?

Love your articles. Thank you.

I usually use the rule of large numbers, where I real off a hundred shots in the hope of getting a “keeper.” :-O

I’m a big believer in the rule of thirds and feel it’s very effective for landscape and portraits. I find it less applicable to wildlife. Especially when the subject is long. I personally don’t think the lizard’s eye should be so far to the right in the photo above. Usually when the subject is long and facing one side of the frame, I like to leave more space in front of it. Even it means cutting off the tail a little. The left portion of the photo is dark and has little interest. Hey, it’s just my useless opinion :)

Thank you, Chris, and that is not a useless opinion at all! I’ve experimented with cropping this image slightly or moving it in different directions, and this was the frame I settled on, regardless of the rule of thirds (which I try not to think about in general). But because the lizard’s eye does align so closely to the rule, I figured it would be a good way to start this article :)

Hi! I enjoy your articles. Your notifications pop up in my desktop at work and I save to read later or at lunch time, like today. You have very good information and I wanted to ask you how does the rule of thirds apply to Instagram if you keep your photo square.

See my point above Clarissa. The ‘Rule’ of Thirds applies equally to whatever size rectangle your whole frame is, from a square to a wide panorama, just divide it into 3 equal portions horizontally and vertically.

I have read some ‘advanced’ discussions suggesting that just outside the 3×3 grid intersections might be better for square frames, and just outside the 3×3 grid intersections on the horizontal lines might be more pleasing for very wide shots, but such thoughts are obviously very dependent on each specific picture.

Thank you very much!

The rule of thirds is a good starting place for many people. However, it shouldn’t be called a rule but a suggestion. Same as things like Dutch angle, golden ratio, etc. They are great starting points for composition and seeing but they can’t be treated as a magic formula for a lack of strong content.

Although I tend not to find the rule of thirds especially useful while taking pictures in the field, that’s a personal decision for my own photography, and many photographers clearly find it to be a useful guideline (or something more). So, I think it was important to write this article, even though I completely agree with you that the rule of thirds is not a universal formula for capturing great images or great compositions!

The ratio of the sides of 35mm FX film (and linked formats) is 36mm:24mm = 1.5:1

The ratio of a typical TV is 16:9 = 1.66:1

These ratios were chosen because of the stereoscopic nature of human vision.

The ratio of A4 paper is 2^1/2:1 = 1.41:1, that provides the practical advantage of being able to fold in half (or tape together on the long edge) and maintain the ratio, which makes manufacturing more efficient.

The Golden ratio is 1:(1+5^1/2)/2 = 1.61:1, which happens to be the ratio of growth that many plants, trees and some animals show one stage to a next (typically annual).

The reason these ratios are also ‘pleasing’ to the human eye is because the are to an extent ‘natural’.

Overall, a very useful guide to consider when circumstances allow, which often makes the result look better than an unconsidered composition. The confusing thing is that the Rule of Thirds works even if the whole frame is square or even panoramic, it doesn’t rely on the print itself being in the 1.5:1 ratio.

Hi Burghclerebilly

Liked your answer to John Arcuso’s statement and I think you pinned it down with this: “…a very useful guide to consider when circumstances allow, which often makes the result look better than an unconsidered composition. ” Spencer’s article are aimed clearly to those who until now have had no real ideas how to compose a photo. The discussions whether there are rules we all do (have to) follow while looking at art (a painting, a sculpture, even a photo…) are very, very old. We maybe learned or heard in art history classes about them. Maybe we should consider that art by definition is independent of any rule and therefore has the freedom to follow rules. Rules help (e.g. the beginners) to make the first steps and rules help the observer to understand.

It is not just the photographer but also the public, those who care to take a look: We are all trained in a certain way which means nothing less than we all follow rules. Be it consciously or unconsciously. Denying rules might as well be the origin of something very creative or the origin of failure.

Cheers!

-jan

Thanks Jan,

Yes, although most artists I’ve met often struggle to explain what they are doing in compositions, I have found that they typically also have studied the history of art and picked up many such composition ideas somewhere in their formative years.

Another way to experiment with RoT is to force yourself to apply it in every shot (including making precise crops in post) for a period of time / project, as a kind of way of saying that your own judgement on composition isn’t reliable. Basically, pretend an editor is checking every one of your shots and adjusting them to a RoT arrangement initially. By forcing yourself to start with a RoT composition, you can then experiment with breaking the boundaries. I find that can help speed up the post processing my wildlife work where the initial framing is normally not controllable.

Thanks Burghclerebilly. Yes, many artists got the ideas before and they internalized what they have learned or experienced. They got a “feeling” for what is a good composition.

To crop later to fulfill rules is an interesting approach but that needs a high resolution camera. My neighbour at work is a film producer for more than 30 years now. He told me that his world changed radically. Not a long time ago every camera position, every framing, every angle, every panning, whether it is going to be a closeup and so on was carefully planned before the shooting. Of course many do it still this way. But now some scenes are shot from different angles at the same time with very high resolution cameras. Camera movement (panning), zooming, cropping etc. is done in post processing.

To me such an approach appears less ideal. I think it is better to know what you want before the exposure.

When I got my D800E (36MP) I played around with cropping because such a high resolution gives you the freedom to do so. I got a bit sloppy thought to “recompose” e.g. to the RoT later. But soon I realized that this would not make my photos any better but it had nevertheless a learning effect. I invest even more time in composing now than before. But sometimes, of course, if the initial framing is not controllable, cropping later is the only way to go.