Photos of wildlife are taken in the wild. But… is that always the case? Sometimes it’s just the opposite, as revealed today in my interview with Tomas Grim. Tomas is a scientist, traveler, and photographer who enjoys turning the concept of “wilderness” on its head.

Tomas has authored hundreds of scientific and popular articles. He is also a co-author of the extraordinary book The Cuckoo: The Uninvited Guest, which won the BB/BTO Best Bird Book of the Year award in the UK a few years ago.

As a scientist, he is in the world’s top league – Tomas is the only Czech researcher to be included in Stanford’s list of the world’s most cited scientists, in the lifetime categories of “Behavioral Science” and “Ornithology.” He earned his professorship at the age of 41, only to give up his scientific career a few years later to pursue his passion in bird(watch)ing (as he likes to phrase it).

For many of us, birdwatching (or bird photography) can be relaxing activities. In Tomas’s case, though, it turned into a battle for the top spot – as last year, Tomas fulfilled one of his dreams and accomplished his “Big Year.”

For those of you who don’t know what the Big Year is, I recommend watching the movie The Big Year. In short, it’s a competition to observe the most bird species in one year. Winning The Big Year for a birder is like winning the Stanley Cup for a hockey player. So, how was Tomas’s Big Year? Within the Western Palearctic region, he ended up at No. 1 in the international eBird rankings with a total of 501 species observed.

But today’s conversation is about a discipline that Tomas has gradually developed as a sort of by-product of all his other activities: photography. And since Tomas does very little at half throttle, he is breaking new ground and finding success in the world of photography as well.

A few months ago, when I was looking at the nominated photos in the Czech Nature Photo Competition, I noticed some familiar scenes – a few that you took when we were shooting together, here in Prague. If I counted correctly, your photos were nominated in four categories. I can’t say I’m particularly surprised, knowing how much energy and time you put into it. What kind of photos did the jury choose?

All the nominated pictures, I took last year for two books I’m working on. One is about urban birds, and the other is about invasive species.

Let’s start with the photo that I personally found the most interesting. Can you guess which one it is?

Jackdaw versus Fulmar?

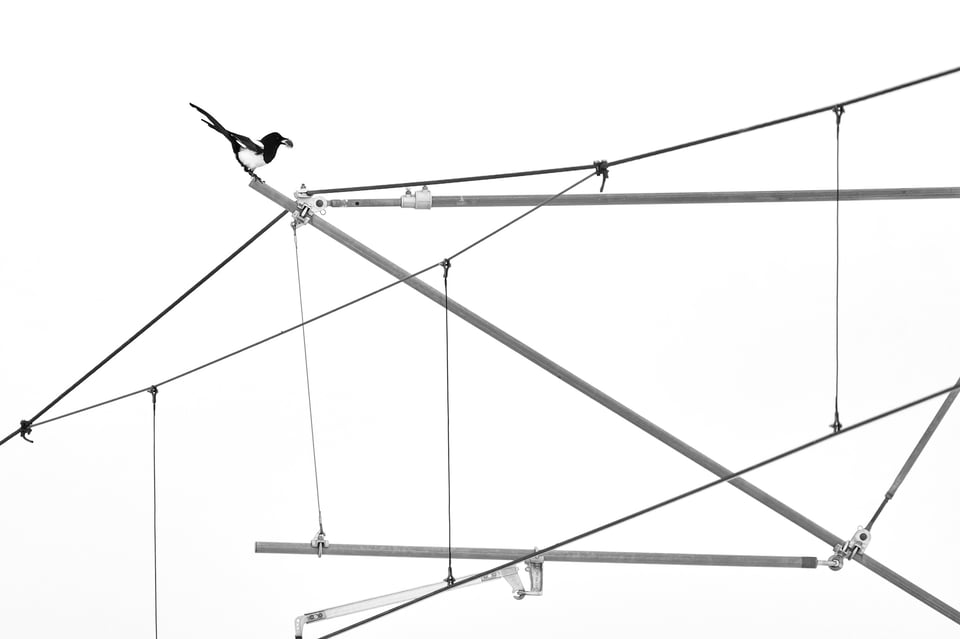

That’s the one! This is a clear winner for me. How did you come up with this strange geometric photo, Tom?

It came about in my usual way, by urban wildlife photography.

Let’s say I’m walking through the city streets with my eyes and ears open, looking for interesting motifs to photograph. For me, an urban photo is first and foremost about clearly acknowledging that the scene is in an artificial, industrial, busy environment that is hostile to life… but only seemingly.

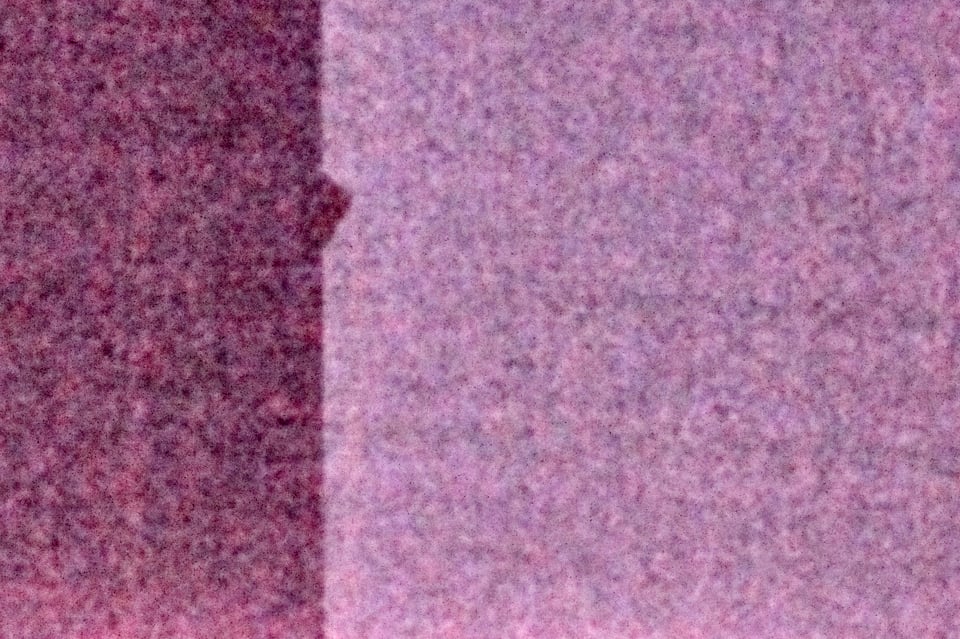

As for this picture, it is not, as some think, a photo of a bird’s shadow. Rather, it is a silhouette painted on the side of the house by a homeowner. Old houses have been covered in polystyrene in recent years for insulation, and such insulation is preferred by woodpeckers – so, homeowners have added motifs of birds of prey in an attempt to scare them away.

I was trying to find an appealing example of this painted silhouette that could make a compelling photo. I visited all over the Czech Republic, to dozens of housing estates. Paradoxically, I found the most interesting motif close to home in Olomouc.

Does it actually work, to paint these silhouettes?

The effectiveness of the silhouettes is zero, as is clear to anyone who knows anything about bird behavior. In fact, if there is any effect at all, it’s the opposite. Woodpeckers like the darker places more because they remind them of dead wood. Therefore, they carve right into the painted areas.

It’s also clear that some homeowners have a rather loose idea of what a raptor looks like…

Another nominated photo of yours is from the “Animals in their Environment” category. A few months ago, you and I were discussing which version of photo to choose for your submission. The tram passing in the background was the deciding element, wasn’t it?

I made over a hundred different variations, varying shutter speeds, composition and background. Then deciding whether to use the one with people walking, trams running, or the cold pavement. In the end, I chose the one you see below. The blackbird has just the right “contact” look. It pretends it’s not there – and quite successfully.

Of the many different trams that whizzed along the Eurasian Blackbird nest, I chose this particular photo because it has complementary colors on it – and also colors that are repeated on the Blackbird on the nest. To me, this photo aptly describes the extremes to which birds that choose to coexist with humans can go.

The streak of colors also creates a Czech tricolor, which nicely places the photo in its geographic context. Great bonus. But to continue, what was your creative intention for this photo?

In a word, I wanted to create a “birdscape.” That is, a feathered creature in its larger environment.

The guarantee with photos like this is that viewers will react negatively or not at all! Most of the time, I think people are more likely to respond to a classic handbook shot where the animal fills the whole frame, and the background is mashed peas. This template works if you are selling photos. But there is zero creativity. It’s always going to look good, but is it going to look special? It’s been done before. I expect something more from a photo.

Often, I like photos where the animal is not filling the frame, but rather the opposite – even 1% of the area of the photo might be too much. Thus the viewers have to search for the main subject for a while, but in the process of that search, they learn a story, a context, and a background. Voilà!

Photographing birdscapes can be a pretty good recipe for photographers who don’t have a long telephoto lens. I see a bird sitting on a garbage can somewhere 30 meters away, press the shutter and I have a birdscape par excellence. But I guess it’s not that easy, is it?

Quite the opposite. The problem with a birdscape is that it’s actually two photos in one. The bird has to be photographed properly, which is not always easy. The same goes for the second part of the word, the “scape.” Most importantly, there has to be an interaction where the two elements fit together.

Often, you’ll find in the field that you’ve got an interesting bird and the landscape around it, but you’d have to float seven meters off the ground to make it fit together exactly.

When I think about photos like this, I believe that a good birdscape would work even without the bird.

Absolutely. A birdscape is primarily made by what is around the bird. That would actually be a good litmus test for the success of a birdscape photo: If it still works after the animal is “cropped out”, the photo is okay. Maybe wildlife competitions could add a new category, “Environment without its animals”!

In almost all of your images that made it to the competition shortlist, the bird species is something common that we see at every turn in the city. I mean, you could almost say “junk” birds. It’s quite remarkable to want these birds to compete with attractive, exotic species.

Urban birds and other urban creatures have several deep planes of meaning. They are an excellent choice for telling stories as a wildlife photographer.

We, humans, will flee cities for nature when we find cities unbearable. Birds, on the other hand, leave the open countryside, which is becoming uninhabitable for them, and move in the opposite direction, into the noisy, polluted and dangerous cities!

For example, in Prague, where we are right now, there is a much greater diversity of bird species than in the surrounding countryside. Paradoxical, but true. The surrounding countryside is mostly fields or groves, and these provide little in the way of food and nests. In contrast, the inner city of Prague contains a fantastic variety of different types of environments, ranging from forests to various types of water bodies, wetlands, rocky steppes, and so on. This makes the city much more interesting than one would naively assume at first glance.

Is the city much more interesting when it comes to photography, too?

Absolutely! We fools always go to the other side of the world to photograph.

But ironically, that results in virtually the same photos by different photographers. A toucan on a nice cecropia, a hummingbird on a flower… Nothing against it, I often take pics like that too, but it’s been done a thousand times before.

In truth, the thousandth photo of such a subject, no matter how technically perfect, doesn’t appeal to me much anymore. It’s nice but boring. That may be why I’m drawn to the city. It offers possibilities for wildlife photography that the forest does not. Or rather, it offers a much wider range of possibilities.

Not to mention, there is a forest in every city as well. It’s called a park. There is a rocky face in every city, called buildings. In fact, there are all kinds of natural environments in cities, as well as unnatural ones – from ancient monuments to ultramodern architectural avant-garde. And combinations of all. Inevitably, the amount of different “backgrounds” a city offers is orders of magnitude bigger than any other environment on the planet.

Do you look for anything in particular when you’re doing urban wildlife photography?

Opportunity makes the photo… but I like it best when I manage to get an inscription, a structure, or maybe a road sign that takes the photo to a paradoxical level, an irony, a joke.

And of course, I like if I can incorporate people in my photo – whether they are indifferent to the birds I’m photographing, or interacting with them in some way. A human adds a whole new dimension to the photo.

The place where the photo was taken can mean a lot, too. A photo of, say, a House Sparrow in New York’s Central Park – where the species was first released in North America – can have more significance than a photo taken elsewhere. It’s supercharged with meanings.

Is there any group of birds that really isn’t attracted to cities?

Cities certainly don’t attract raptors, for one thing. But when you meet an exception, it’s amazing. My visit to Berlin last year comes to my mind. I travelled there for a documentary photo of the Northern Goshawk.

Berlin is the only city in the world with a relatively large population of Goshawks. About 100 pairs nest there! And really, in the few days I spent in Berlin, I met as many Goshawks as I meet here at home in about two or three years combined… and I have Goshawks nesting barely half a kilometer from my home.

In the woods, a Goshawk will never let you get too close. Once you get within 200 or 300 meters, it just disappears. In contrast, I could view the Goshawks in Berlin from seven or eight meters away without scaring it. Maybe it didn’t fly away because it was feeding on a Blackbird it had caught. Incredible experience.

The Northern Goshawks in Berlin have lost their shyness and thus gained access to this richly set table full of careless prey that hasn’t seen a predator for generations, correct?

Exactly. The loss of shyness is probably the primary reason why some species go to cities in the first place. If birds in the city is shy, they will be constantly stressed and will not have reproductive success. They’re just not going to be able to sustain themselves in the city, and there are few benefits for shy birds in the city in the first place.

Since you mentioned Berlin, can you think of other cities where the nature photographer’s heart rejoices in their urban wilderness?

It’s hard to recommend because cities are changing continually. For example, I shot a scene in Seville last summer that will definitely be in my upcoming book. In that scene, I went back in time about a hundred years, to a time when House Sparrows were extremely common even in largest cities. This was before the advent of the automobile, when the horse was the main mode of transportation. There were plenty of House Sparrows in the cities because they fed on undigested oats from horse manure.

Back to the present, photographing Seville Sparrows in Seville was quite a technical challenge. Seville is, along with Cordoba, the hottest city in Spain. The thermometer read 47 degrees Celsius (116 Fahrenheit). With the heat distortion in the air, it was almost impossible to take a sharp photo. In the end, I more or less managed it, but it took hours of work. When I returned this year to try to get a different or better shot, the scene was no longer there. Cities are constantly changing.

So the House Sparrows are gone…

Not at all! They live on every continent. The House Sparrow is usually the first species you see after leaving an airport anywhere in the world, as you know firsthand, Libor. It’s still by far the most numerous bird species in the world, an estimated population of about 1.6 billion individuals.

It’s hardly found in some areas, like in London, no question about it – but that’s completely irrelevant. What matters is the whole picture. Globally, the House Sparrow is the very last bird species that we should be concerned about.

What other cities should birdwatchers keep on their lists?

Lately, I’ve started to develop a concept where I choose an “emblematic” bird for particular cities. A sort of advertisement or a recommendation for both photographers and birders. Just as Berlin is The City of the Northern Goshawks, London is The City of the Peregrine Falcons. Nearly a hundred pairs nest in Greater London.

New York, on the other hand, is The City of Hawks. There are the famous Red-tailed Hawks that nest on skyscrapers. I was in NY for three months at one of the universities, and almost every day on my way to work through Central Park, I would meet a group of birdwatchers with cameras and binoculars looking up at one of the nests. What a fantastic scene! Unimaginable for me, a European. By the way, sometimes it’s more interesting to photograph the birders and photographers than the birds.

And while we’re here in Prague, you would call it The City of …?

Well, it used to be The City of the Eurasian Sparrowhawks. Prague had its primacy in that you could see tens of pairs nesting right in the center – a Sparrowhawk flying between the houses down the street, wow! But that’s over now. They’ve disappeared in the last few years. So I’d probably call Prague The City of Mute Swans now, as you yourself once suggested. The Vltava river is literally crowded with them in winter.

And I can think of another city, Olomouc. Last year you won a Special Award for an Outstanding Project in the Czech Nature Photo contest for a series documenting the first nesting of the Eurasian Scops Owl in the Czech Republic in an urban environment. You have great photos there, but one of them stands out because of a certain technical peculiarity. Do you know where I’m going with that?

Yes, I’ve privately renamed this award the “Special Award for an Outstanding ISO”!

Just as a reminder, what was the ISO?

I was shooting at the very limit of what I could set on my Nikon D500. I needed to get a picture of the Scops Owl, but because it was such a special event, I wanted to disturb it as little as possible. No flash, no flashlight, no light other than distant streetlights.

The nest, however, was 21 meters above the ground, in a cavity in the insulation on the unlit side of a hotel building. Also, Scops Owls are only active in total darkness. So, I ended up turning the ISO up to H5.0. That’s ISO over one million – I didn’t even know that was possible! But it was definitely not a creative choice of mine. It was just a technical limitation.

There was basically nothing I could do about it in post-processing. When I used DxO PureRaw on it, just an unusable trash came out. In the end, I just left the photo as it was.

I’m not surprised. I guess no one trained the program’s machine learning on such a huge ISO. Only a fool would use such an ISO in a real situation… or Tomas Grim.

Thanks for the compliment (laughs). I fought as hard as I could to get this shot, because it proved that the Scops Owl had nested for the first time in a Czech city, and only for the second time ever in our country. Hundreds of people from all over the Czech Republic came to see it, which was unprecedented in a country with quite limited birding tradition.

And it dawned on me that the photo was not “only” historically significant. Unintentionally, it had an aesthetic charge, summing up everything unclear, dark, and mysterious about the nightly hunt for the Scops Owl. It was powerful.

The photo also reminded me of a classic Italian film from the 1960s, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up. In it, the grain is basically one of the main heroes. Just like in the case of the super-grainy Scops Owl photo.

Tom, to anyone who photographs animals, it’s clear that the biggest problem is finding the animal in the first place. How do you locate attractive subjects to photograph? That must take a lot of time, especially in urban wilderness.

Absolutely. Last year alone, it took me several months to find subjects Czech Republic, and a similar amount of time abroad. It was a sort of public affair, too – I received great help from fellow citizens when my Facebook appeal resulted in lots of tips for interestingly placed nests. I am immensely indebted to them.

However, sometimes I was lucky. I would stumble upon a place with just the right motif. That’s what urban photography is about too.

It reminds me of your story to photograph a family of blackbirds, literally under the protection of St. John of Nepomuk.

I got the message about that special nest at the most inconvenient time, between a couple of TV and radio appearances and an upcoming trip to Turkey. I received a smart phone photograph of the scene and was completely blown away – it just had to be in my urban bird book!

However, the Blackbird nest under St. John of Nepomuk’s nose was on the opposite side of the country. The only gap in my super busy schedule arose because I need to go to Prague to give a radio interview. In a live interview on Czech Radio, towards the end, I told the presenter, Lucie Výborná, that I had to run to catch a train! If I had missed that particular connection, I would have missed the only opportunity.

When I finally got to the nest site, I had to wait about three hours for the sun to move. I put off my departure until the last minute. Eventually, it all came together. I got the photo and caught the last train. It was nerve-wracking, but worth it.

How do you feel about editing your photos?

For me, it’s absolutely essential that the photo reflects reality as faithfully as possible. To make a photo that is not real but digital would be the complete opposite of what I want to show in my articles and books. I want reality, be it beautiful or ugly. Cities contain all of this to the extreme, and that’s what urban ecology and aesthetics is all about.

I think I know your opinions, then, on artificial intelligence, where you get a computer-generated photorealistic image based on some prompt.

What you’re describing is the exact opposite of what I find interesting and meaningful about photography. The worst raised to the tenth power.

When I teach anything to people, it’s important for me to write or lecture only about what I’ve seen with my own eyes and photographed myself. Any article in which a journalist uses a photo from a photo bank, or worst of all an AI-generated photo, automatically lacks any authenticity.

What would be the point of a lecture about Australia, for example, if it was based on the fact that you generated the photos of kangaroos on Midjourney and read about the country on Wikipedia, if Croatia was the furthest you’ve ever been in your life?

Thank you for the interview, Tom!

My pleasure.

This interview was conducted partly at my home and partly on the bus on the way to the Czech Photo Center, where this year’s Czech Nature Photography Awards were held. And how did it turn out? Two of Tomas’ four nominations were awarded first place by the jury. The award for the best photo in the category “Animals in their Environment” went to “Dynamic World of Townies,” and the award for the “Best Bird Photo of the Year” went to “Why Fulmar?!” – meanwhile, Tomas’ series “Life of Feathered Townies” won second place in the Series category, and “Emotions” (shown above) won third place in the Nature in Prague category.

PS: Very recently I learned that Thomas’ photo “Why Fulmar?!” was shortlisted in the prestigious Bird Photographer of the Year competition.

Well-conceived article (well done Libor) and great interview with even better pictures. I have now finished my recently acquired copy of Cuckoos and adored it. I am recommending to birding friends and anxiously await Mr. Grim’s next book.

Thank you, John. I am pleased you enjoyed The Cuckoos. I hope my upcoming books will be available in English, too.

“Judging is now completed, and I am pleased to inform you that your image ““why the Fulmar?!”” has been chosen to be included in Collection 8 of the competition book. Well done!

This is a great achievement. There are fewer than 300 images chosen to be included in the book, which puts you in the top 1% of images in the competition.”

As this message came from the prestigious Bird Photographer of the Year 2023 I can just say: REALLY? ( ;-) ) Will see when the BPOTY book is out later this year.

Nice pictures and a very interesting article.

Here in Nuremberg, Germany we have also a well documented peregrine falcon population in one oft the towers oft the middel age castle.

lebensraum-burg.de/Wande…rchiv/2023

Great to see such details from the life of such wonderful creatures as peregrines. And thank you for your kind words.

Just yesterday I came across a falcon during an afternoon hike near our cabin. And since I see it regularly in this area, the idea to take a picture of it is growing in my head. But there is only one small catch, and that is to climb a rock tower about 30 meters high with a camera. The falcon seems quite used to human presence, as it was perched on top of the rock tower only about ten meters from the climber belaying his friend below. Will you do it with me, Tom?

Nice idea, Libor. Will join you as… an background support in the nearest pub – the URBAN wildlife, you know… ;-)

Great article and cool and funny photos, thank you!

Thank you for your kind words, Marcin.

Thanks for sharing this interesting article. Melbourne (Australia) has Peregrine Falcons with a Iive-stream when they are nesting at a particular skyscraper.

367collins.mirvac.com/workp…67-collins

Thanks for the link, I’ll set an alert for nesting time :)

Hi from Bolivia, recently we saw a peregrine here too – what a bird, one of the half dozen cosmopolitan birds among 11 000 species.