There’s a long and sordid history behind staging and faking wildlife photography. It’s anything from lying that a zoo photo was taken in the wild, to baiting wildlife, to even killing and then staging the corpse of an animal.

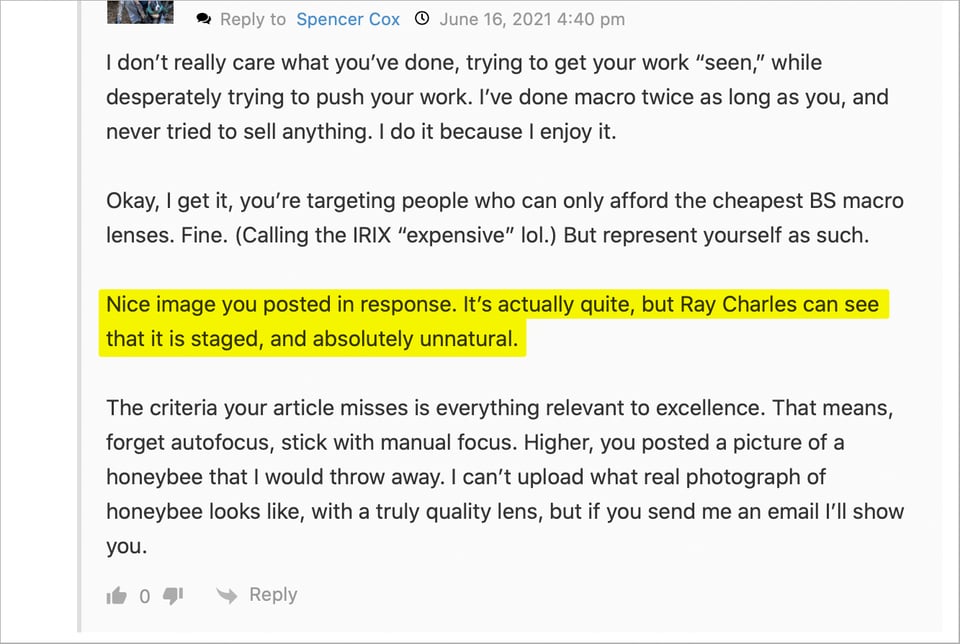

I find all of those things awful, especially staging the wildlife in an unnatural way by killing it or harming it to get into a pose they’d never normally do. Which brings me to this comment on one of my recent articles:

Here’s the photo he was referring to:

This is the first time anyone has accused me of such a thing, and I don’t think many people would take his evidence-free claim seriously. But I wanted to make it clear in case anyone ever wondered something similar, since I agree that it’s unusual to see a lizard on such a fragile-looking plant supporting its weight. I didn’t fake the photo in any way, nor harm the lizard at all.

Some photographers do harm their macro subjects, often by using fishing line to string out their subject into unnatural poses, or freezing them (yes, literally putting them in a freezer or refrigerator) and then placing them how they want. You’ll periodically see articles like this or this exposing photographers who use that process.

It’s actually a serious problem in macro photography. Not only is it frankly sociopathic to take beautiful photos of such amazing creatures while secretly torturing them, but it also undermines the credibility of macro photography as a whole. If our hobby becomes known as a haven for animal torturers, who in their right mind would want to become a macro photographer?

So, to be clear, I do not fake my macro photos. I don’t harm my subjects. And the macro photo in question was not faked.

In fact, it was one of the most amazing moments I’ve ever seen as a macro photographer. I was out at Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge in Florida to photograph damselflies at sunrise. My dad had tagged along, and he spotted the lizard in the most delicate of plants, sunning itself in the morning. Since it was just after dawn, the lizard was still a bit sluggish, and I was thrilled that it didn’t run away as I approached slowly with my camera. I ended up taking the photo in this article as a result.

I realized afterwards that the type of lizard is an anole (this one is probably a mix between a brown and green anole), and it’s sitting in a type of plant called pampas grass. While I’ve only seen an anole in pampas grass like this a few times, it’s something they do from time to time. You can see this photo and this photo from other photographers to show that an anole lizard in thin pampas grass is not an uncommon sight.

The bio at the bottom of my articles on Photography Life – where it says I was exhibited at the Smithsonian – is thanks to this photo winning the Youth category for the Nature’s Best Photo contest in 2016. It’s the only big photo contest I ever won outright, but even if I never had, this photo would still hold a place as my favorite and most special picture. An accusation of faking it was deeply painful. The Smithsonian already vetted it as a real photo before the exhibition, and more than that, I was there. And my dad was there. It’s a real photo of an amazing moment that we saw, and even though I took that photo in 2015, I have yet to take a better one. Maybe some day I will.

I hope my reputation speaks to why I would never fake such a photo anyway, but fortunately, I took a short video of the subject at the time, so you don’t have to rely on my reputation alone. This is the lizard that I photographed, as filmed on my iPhone 3 (!) at the time. Sorry for the vertical video; this was in 2015, and I have since repaired my ways:

(YouTube adds a lot of compression to their videos; the uncompressed video can be downloaded here.)

I’ll even take the unusual step of showing my full-resolution RAW file here, to prove that there are no wires or anything holding up the lizard:

Here’s another photo I took of the same lizard, from the other side, before it scurried away:

And here’s that photo’s full-resolution RAW file:

There are no strings. The lizard moved positions between the two photos, and also at the end of the video. The lizard is gripping the plant with its own hand. It’s impossible to fake that, with the possible exception of a dead lizard, which this clearly isn’t.

Heck, I took this on a trip to the beach in Florida with my parents as a teenager. My dad was the one who drove me to that location before sunrise. I’m happy to say I have no desire to torture lizards under any conditions, but in this case, my parents literally would have disowned me if had been freezing lizards or stringing them up with fishing line during our family trip.

So, yeah. Not a faked photo.

But I was lucky here to have all this evidence behind the photo, from my original RAW files to the video I took. Plus, the guy who’s accusing me is just some random person on the internet rather than, say, a reputable photo contest judge. If you happen to find yourself in a more serious situation than this, how can you make sure that you’re defended against claims of fraud?

While it’s hopefully not something that is likely to happen, or at least that you’ll be given the benefit of the doubt, there are a few things you can do to back yourself up. First, whenever possible, try to take multiple photos of your subject, and shoot in RAW rather than JPEG. It’s almost impossible to fake things under those conditions. Remember the anteater Milky Way guy? I won’t pass judgement on whether he faked that photo or not, but if he didn’t, any other photo of the subject would have proven it.

Second, if you’re a multimedia kind of person anyway, you should consider doing some video while you’re out in the field. I was lucky to have filmed this lizard briefly with my phone, but that’s not always the case with my work. I especially recommend taking some video if you know you might have just captured a really good photo, and something about it means the photo could have potentially been faked (i.e., the background looks like it could have been a zoo). Taking a video of the subject in its surroundings is a practically foolproof way to head off accusations of fakery.

Finally, if you’re with any other photographers, it ramps up the difficulty of faking your shots. Maybe “Joe Shmoe” photographer could have faked a macro photo on his own, but not if he’s out with his whole photo club.

While this article is ostensibly in response to just one guy’s comment, it’s also about ethical photography as a whole. The very fact that photography has had so many scandals is what leads people to have such cruel opinions in the first place. “The better the wildlife photo, the more likely it was to be faked.” “Wildlife photographers couldn’t care less about their subject if it makes a great photo.” “Photographers only care about money.” (Well, no one would say that last one after looking at our average salaries, but I’ve still seen people say it!)

In any case, none of those opinions are true. But the more unethical examples and scandals we see to the contrary, the more common those opinions will become. And people will think less and less of photographers as a whole. So – don’t harm the wildlife that you’re photographing.

Spencer I have a question regarding photography ethics that this article brings up. My family enjoys trout fishing. What is your opinion regarding taking photos of the trout that we have killed in order to eat?

I think it’s a different scenario, unless you are posing the trout dramatically underwater in order to make it look alive – and then lying to people that it is!

Spencer, I’ve been trying to locate the original comment in context but I’m having a hard time finding the article and the contributor’s original comment. Can you point me to it?

It was in our Best Macro Lenses for Nikon article, but I deleted the original comment because some people were targeting the photographer who made it, who posted identifiable information.

Great photo but never feel you have to prove yourself to internet trolls. Ignoring them bothers them the most…keep up the good work.

Very true, thank you, Jerry.

Awesome photo Spencer. Awesome content like always

Much appreciated, Vikas!

In our yard in Western Travis County TX near Austin, we have scores of anole among other species of lizards. I have photographs of two anoles in a territorial dispute on the leaf of a red yucca which is at least as “fragile” as the stems in your image. No problem supporting them and regularly see them on foliage that is even less robust. I’m not sure what you mean by a mix of brown and green anole. Anoles change color. I have seen them change from green to brown and then back many times.

Ah, that sounds awesome. I can imagine it’s a great photo.

I knew that anoles change colors but was still under the impression that brown and green anoles were separate species that sometimes interbreed. I’m not sure which one I photographed – looks browner in one photo and greener in the other!

Those little anole are quite light so it’s not that unusual to see them on such fragile material. They are so light that if it weren’t for their body temperature, it would be hard to know one was in your hand if you held it. I have held them. When I first saw your photo a while back, it never entered my mind that it was staged. I’ve seen many of these in the wild on all types of plant material.

Very kind of you to say! That’s very cool. I figured they were light based on where I’ve seen them perched, but I’ve never held one before.

Estimado Spencer Cox:

Mucha gente estúpida y envidiosa busca la manera de fastidiar a quien triunfa y es admirado como tú. Creo que no debiste darle gusto a esa persona equivocada, dándole tanta explicación. Tú sabes que esa foto es auténtica, y tuviste la amabilidad de compartirla con nosotros, y eso es suficiente. Allá él si no lo cree, al igual que cualquier otra persona que lo dude. Yo creería que quien te inculpó de fraude ha de ser el primero que haga trampa al tomar y mostrar sus fotos.

Se nota que te tiene envidia.

Gracias, más bien, por tomarte tu tiempo en compartir tus conocimientos con nosotros tus lectores.

Saludos cordiales desde Quito, Ecuador, América del Sur (desde la mitad del Mundo).

Nota: Pido disculpas por escribir en Español, es el idioma que hablamos en mi país.

¡Aprecio que lo digas! No necesitas disculparte. Gracias por las amables palabras

/

I appreciate you saying so! No need to apologize. Thanks for the kind words.

Helluva nice shot. When you get out and look around magic like that happens. Grateful you had the skill to capture it so elegantly.

Glad you like the photo! Thanks for saying so.

The first amendment brings our the very worst in some people. Don’t let him get you down. Your photography is world-class. Thank you for sharing your photos and your excellent tutorials. I always learn something.

idd ! Absolutely. Your photography is world-class. Thanks for sharing your photos and your excellent tutorials. I always learn something.

Very kind of you, thanks, Richard.

Pro tip:

You could have easily said:

It’s not fake and your belief is not required.

Done.

That’s true!