I just realized that I’ve been doing photography seriously for ten years (plus some change). So, I’d like to take this chance to look back and share ten of the most important things I’ve learned along the way, in chronological order.

Table of Contents

2012: JPEG Has Consequences

The first trip I took with a “serious” camera (the Nikon D5100) was to Oregon and the Pacific Coast in the Northwest United States. I daresay that most of my photos were awful, but I was having fun, and a couple of them didn’t turn out so bad.

Unfortunately, I shot all but a handful of the photos during the trip with highly compressed JPEG settings. They looked fine on the back of my camera, but when I brought them back to my computer for editing, I noticed the issues right away. Blocky details and weird artifacts up close. Colors and highlights that I couldn’t shift without strange results. And harsh sharpening artifacts on all the edges in the photo. (That one was my fault for setting in-camera sharpening to the max!)

Anyway, I know that shooting raw files isn’t for everyone, but if you’re a dedicated photographer who wants to edit your photos much at all (hey, like almost everyone reading this!) go for raw.

I was lucky to get this photo before I really knew much about photography. I was unlucky to shoot it as a highly compressed B&W JPEG.

2013: Practice Is Key

The lesson I realized next was even more important than shooting in raw, and possibly the most important thing I’ve ever learned as a photographer. Practice is the best – and possibly only – way to improve.

It’s clearest at the beginning but applies no matter your skill level. For the vast majority of photographers, your later photos will be better than your earlier photos.

When it comes to practice, it doesn’t matter whether you’re in the most beautiful scenery in the world or whether you take pictures in your backyard. The key is to get some photos and as many hours as possible doing photography.

2014: There’s Value in Prime Lenses

Something that I lacked for a while as a photographer was thought. I was a point-and-shoot photographer even though I had a DSLR. It took a couple years (at least) before my best photos were the result of deliberate effort on my part rather than lucky chance.

I credit this to a few things – practice foremost of all – but switching from a zoom kit to a prime lens kit helped a lot. With primes, the photo you’re about to take often won’t look quite right at first. Rather than zooming until it looks acceptable, you’re almost forced to walk around and figure out a better composition.

This doesn’t mean prime lenses are better than zooms (and my current kit includes some of both) but that for photographers starting out, a set of primes might push you to improve faster than a set of zooms.

2015: Effort Has a Complex Relationship with Results

This is the year I went on one of the most influential trips of my life, to Iceland – the first time I traveled somewhere specifically for photography and little else.

On that trip, I did two of the more difficult hikes of my life. The first was an amazing trail that followed dozens of waterfalls and was filled with photographic opportunities. The second was a 17-mile slog (about 27 km) through swarms of flies and difficult terrain, with very little photographic payoff.

The effort was worth it the first time and not the second. And after I returned home, I realized that my favorite photo from the trip was one of the easiest ones I had taken, just a few hundred feet from a parking lot.

Effort can lead to results in photography, but it doesn’t always, and sometimes the best photos are the easiest to take. Don’t confuse the quality of a photo with how difficult or easy it was to take.

2016: Focus at Double the Distance

To this day, the technique that I find the most useful as a landscape photographer – when my goal is to have an equally sharp foreground and background – is a little tip called double the distance.

You simply compose your photo and look for whatever object in the foreground is the closest to your camera. If that object is three feet / one meter away (horizontally), focus on something six feet / 2 meters away from your camera. When you do, you’ll equalize foreground and background sharpness every time. (Likewise if your subject is any other distance away. Focus at double the distance.)

This equalization happens no matter what focal length or aperture you use, which I find really remarkable. Of course, you still need to use a decent aperture in order to get enough depth of field – but even if you shoot at f/1.4, the foreground and background will be equal in how out of focus they are.

It took me more years to learn than it should have, since the technique is surprisingly little-known, but I’m glad I got there eventually.

2017: Don’t Skimp on Focal Lengths

For several years prior to 2017, my entire kit in photography consisted of (at most) three lenses: a 24mm, 50mm, and 105mm prime. I had been wondering for a while what possibilities I was missing by ignoring the wider and longer ends. Near the end of 2016, I expanded my kit with a 14-24mm and 70-200mm, and I started to realize throughout 2017 how good of a decision this was.

In the years since, I’ve taken at least a third of my favorite photos wider than 24mm or longer than 105mm. That’s not to say everyone needs such a broad range of focal lengths, but if you think you might, go for it – with primes, zooms, or a mix. Even a low-quality superzoom is better than not covering important focal lengths at all.

2018: Broaden Your Skillset

This is the year that I interned at Backpacker magazine for a few months. I had always thought of myself as “outdoorsy” and reasonably good at hiking, camping, and so on. Being around actual experts made it clear that I still had a lot of skills to pick up.

I did my best to pick up those skills when I could, and I put them to the test later in the year when I did a 100 mile (160 km) hike in Iceland with my dad that summer. It’s the most difficult and beautiful hike I’ve ever done in my life, and I took some of my all-time favorite photos along the way. It would not have been possible without broadening my skillset to other, not-quite-photography areas.

In other words, the more I learned about related fields like hiking and camping, the better my photography got.

2019: Image Averaging Is Underrated

Every photographer knows about panoramas and HDR. Most know about focus stacking. But a fourth method of merging photos – image averaging – is much less common, even though it’s just as useful as the other blending methods, if not more so.

I’ve used image averaging increasingly more often in the years since, but 2019 is when I first realized how powerful it could be. Rather than lugging around a heavy, expensive 14-24mm f/2.8 everywhere I went for astrophotography, I could bring along practically any lens and still get excellent image quality at night.

I’ve written about image averaging before, a few times actually (see for star photography, mimicking HDR, and just in general). But it’s one of the more recent “new techniques” I’ve added to my toolbox, and I only wish I had started using it sooner.

2020: Make Time for Photography

This was an awful year in so many ways. Even just looking at the field of photography, a lot changed for the worse. Photographers thrive on travel and meeting people – two things that were severely limited, if possible at all, for much of the year.

2020 is also the only year since I started photography where I have a month (actually more than one) without a single photo in my Lightroom catalog. I simply stopped doing photography for weeks at a time.

When I finally started to get out a bit more near the end of the year, I found that taking pictures helped me feel happier and less stressed. My overall mental state improved as a result of a few weekends here and there that I dedicated to photography.

Most of us are photographers because it’s something we love and enjoy. Don’t forget that, and try to make time for photography whenever possible.

2021: Explore Your Local Areas

I’ve lived in Colorado for just over two years, and while I’ve explored some parts of the state in detail, massive areas are totally unknown to me. I’ve tried to make a point in recent months to get out to places that I haven’t been, and it’s been a great decision.

I also spent a couple months in Florida at the start of 2021 and found several places for macro photography that I had never seen before. So far this year, I’ve taken more photos than any other year, and I’ve spent more days doing photography – almost all of it local.

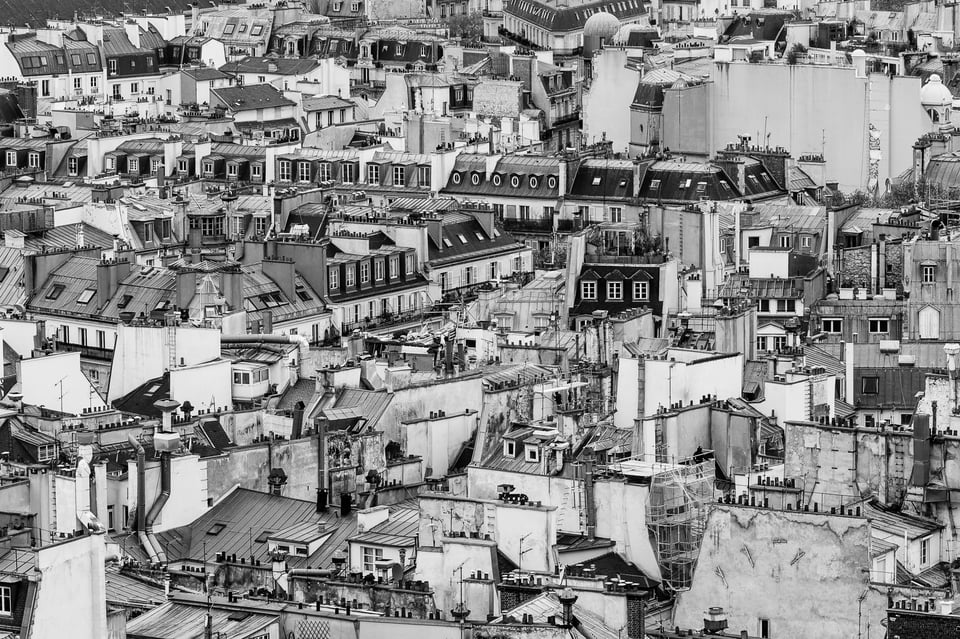

Even if you don’t think you live in an interesting area for photography, that’s almost certainly untrue. See if there are any waterfalls or forests within an hour’s drive from you. If not, what about macro photography opportunities? You can take great macro photos anywhere, even indoors, with a bit of effort. Not to mention that if you live in any city, there are almost certainly some good opportunities.

Photographers can get caught up in the idea of visiting exotic locales and forget that good photos can be taken anywhere. Bring out your camera and go exploring!

When I used Canon gear, I had to shoot RAW and edit everything. After 40 years, I left Canon ( most recent was a 5Dmklll) and now have a Fujifilm XT-3. I still shoot RAW in case I mess up but the Fuji allows me to make so many adjustments before I actually take the shot that the Jpegs are incredible. I haven’t needed to do any post editing since I switched.

There’s nothing wrong with prime lenses. Sometimes they are the best choice for some subjects and some kinds of photography. I tend to rely on them exclusively for street photography, primarily because a smaller a less-obvious system is an advantage, but also because things happen fast enough that often there isn’t time to perfect a composition.

But the notion that using prime lenses makes you a better photographer by making you think more just doesn’t stand up to critical consideration. I primarily use zoom lenses for landscape photography (and a few other things) because they give me more precise and careful control over my interpretation of the subject.

With a given prime there is likely (to simplify a bit) one subjectively best composition, and even that composition may require compromises with a prime that one can resolve with a zoom. For example, with the primary subject occupying a particular area and volume of the composition, the prime gives essentially no control over foreground and background relationships. With a zoom lens I can maintain the desired “volume” of the primary subject in the scene, but adjust foreground and background by moving forward/backward and optimizing the focal length.

Contrary to the frequent claim, it actually requires more thought to optimally use a zoom lens since the variable of focal length (and its effects of DOF, foreground and background, and more) becomes part of the process of working out a composition.

Just because it is possible to use a zoom in a naive way… it does not follow that using a zoom is less sophisticated. And today, the old advice about starting with one normal focal length lens and learning it is better modernized. to recommend getting one decent zoom and learning it before making additional purchases.

Very nice article. I’m so new, I’m still trying to decide on my first Prime. I need it for my first attempts at some street photography. Thanks for the great info Spencer, I have decided that it would be great to start learning some of the techniques you’ve mentioned. That kind of stuff I can learn, when I’m not out shooting!

Spencer! Fantastic article, Some things I knew and others I didn’t (image averaging). Much to learn! Like you, I moved here just two years ago to be outside and learn more about photography. I took a trip with Nasim 5 yrs ago to Ouray and proudly hang those images in my home. Life changing. Thank you Photography Life for all you do!

Thank you Jeanine, I’m glad to hear it! Those Ouray trips are always amazing, very happy you could go on one a few years ago.

Dear Spencer

Thanks so much for sharing about “Image Averaging”.

– Will this technique work for ‘Non-ISO invariant’ sensors which typically has a limited dynamic range? (E.g. the older Canon 5D mk 3).

– Should I shoot in RAW for “Image Averaging”?

(Btw, I hope this technique may benefit Micro 4/3 camera users as well.)

Thanks and I look forward to your guidance.

John

The technique works well for most cameras, but some that suffer from heavy line-pattern noise in the shadows may not get as much recovery as others. The Canon 5D III is one such camera unfortunately, although image averaging still works well for it – just not as well as on some other cameras. Pretty much any Micro 4/3 camera should work flawlessly with the technique. And yes, you should use it shooting raw. Technically it works with JPEG, but if you’re after maximum shadow detail, raw is always the way to go.

Dear Spencer

I’m very grateful for your reply. This is really good news for Micro 4/3 users who prefers a smaller & lighter setup (which includes carrying a lighter tripod) :-).

Thanks for highlighting the fact that the ‘Averaging’ technique don’t work as well for “Non-ISO invariant” sensors.

By generously sharing your knowledge and experiences, you (& Nassim) have both been a blessing to many photographers worldwide.

With appreciation,

john

Dear Spencer

I’m very grateful for your reply. This is really good news for Micro 4/3 users who prefers a smaller & lighter setup (which includes carrying a lighter tripod) :-).

Thanks for highlighting the fact that the ‘Averaging’ technique don’t work as well for “Non-ISO invariant” sensors.

By generously sharing your knowledge and experiences, you (& Nassim) have both been a blessing to many photographers worldwide.

With appreciation,

john

Shooting in RAW has its drawbacks – it’s called Adobe.

Having done my best by my previous MacBook – at 10 1/2 years old it’s now very unreliable. I was running Lightroom 6.14.

I migrated my files to a new M1 MacBook.

All seemed to be fine, till I tried to open LR. It just flashed on the screen and wouldn’t open. Rebooted. The same. And again. No obvious solution.

That’s 10 years of edits lost. That wouldn’t happen with JPEGs!

I’m now trying to save my better images as Tiffs on my old MacBook. Takes about an hour to save 10 images to a memory stick to then get them to my new one for a different piece of software (bye-bye LR).

I can’t just reinstall my LR 6 disc (yes, I kept it) because my D7500 needs 6.14. Will Adobe let me download it?

So I feel that I’ve done the right thing by not buying stuff for the sake of it and now I get penalised because software companies will only treat you right if you keep on upgrading and upgrading and carry on upgrading.

Speaking of that, I worry about photographers and travel. At a recent workshop a nature photographer talked about a trip to Alaska. That seemed incongruous to me – if you care about nature, do you get on a plane for a 12,000 mile trip and the CO2 it entails? Should photographers rather get a train to somewhere more local?

Gear and travel – it’s hard to find the right response.

So you have a 10.5 year old laptop and no backup and now you blame Adobe? I have an 8 year old computer with a back-up solution that is solid and inexpensive. My computer can explode and I’ll be fine. Technology moves forward. It is very expensive and unreasonable to expect software (and hardware) companies to provide legacy support for that long. You need to open your wallet a little more frequently – it doesn’t have to break the bank. Good luck recovering all your image files (I mean it).

Great article! Thanks for sharing your journey with us! Just wondering what happened with your YouTube channel.. personally I really liked the content and your advices – hope you’ll have the time in the future to continue.

Thanks Tamas! I’m planning to do more YouTube content as soon as possible. I’ve had to put it on the back burner recently to write more on Photography Life, but I’d like to do both in the long run.

Nice article! Very helpful.

One more thing to add to your list is to spend more time making photographs that are difficult or extremely difficult. Backlit portraits, flash photography, slow exposure action images, frame filling, fast erratic action, etc. all are challenging styles to the average photographer. There are even rules of thumb such as putting the sun at your back of back shoulder. Using a flash can be too much trouble when you have not mastered the techniques. But if you can master techniques that have a high degree of difficulty, you can separate yourself from the average photographer and make something unusual.

That’s a great suggestion. I started doing macro photography very early on, and it’s so technically demanding that it forced me to learn a lot about photography instead of coasting along. Highly recommended to do something similar.

I might add one recent learning myself after 40 years of photography. While I have been shooting RAW since my cameras support that, the most recent finding is one that no one talks about as an advantage of RAW: with the progress in software improvement over the years you can enhance your photos further some years later. What I mean is, that e.g. noise reduction has made quite a big progress compared to 10 years ago. So pictures that were quite noisy 10 years ago, can be made almost noise free with latest software technology today. And in the future we will see more intelligent software that might enhance your favorite pictures you capture today.

Stefan, you’re right, that’s a substantial benefit of shooting raw images over many years. We’ve already seen it in noise reduction, sharpening, upsampling, and even reducing motion blur. I wonder where else it will apply before long.