Camera manufacturers have gone all-in on the idea of lightweight cameras. That’s almost entirely how mirrorless got its start, and it remains a major reason why photographers switch from their bulky DSLRs today. So, why haven’t lighter lenses caught on, too?

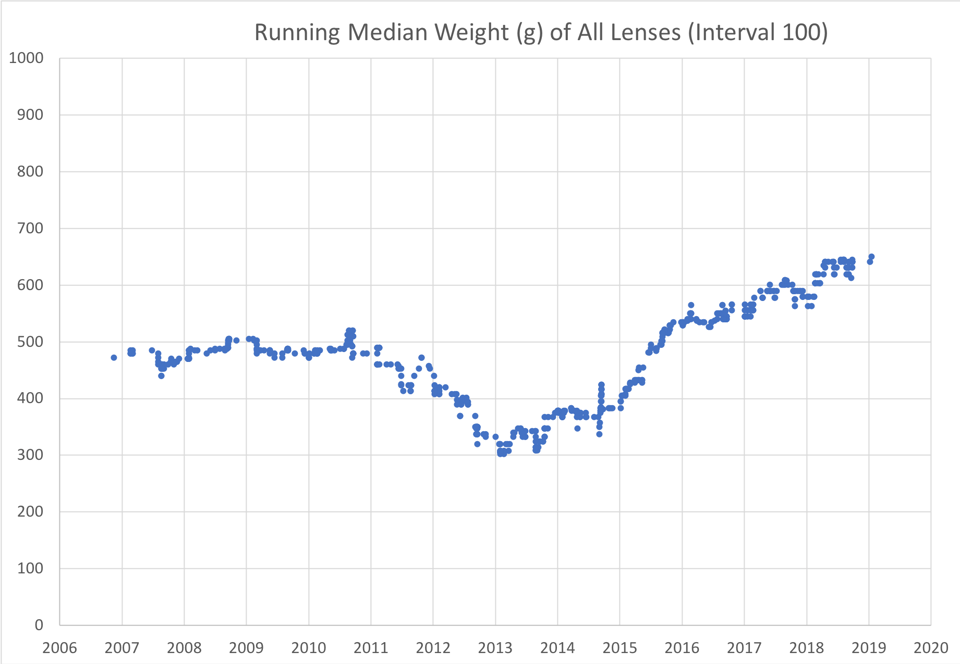

In an earlier article, I analyzed every lens released since the year 2000 and showed that median lens weights have been steadily increasing since 2013:

Today, the median newly released lens weighs about 650 grams. In 2013, that number was less than 350 grams. Depending on the camera system you use, that’s more than enough to erase the weight savings from switching to mirrorless in the first place.

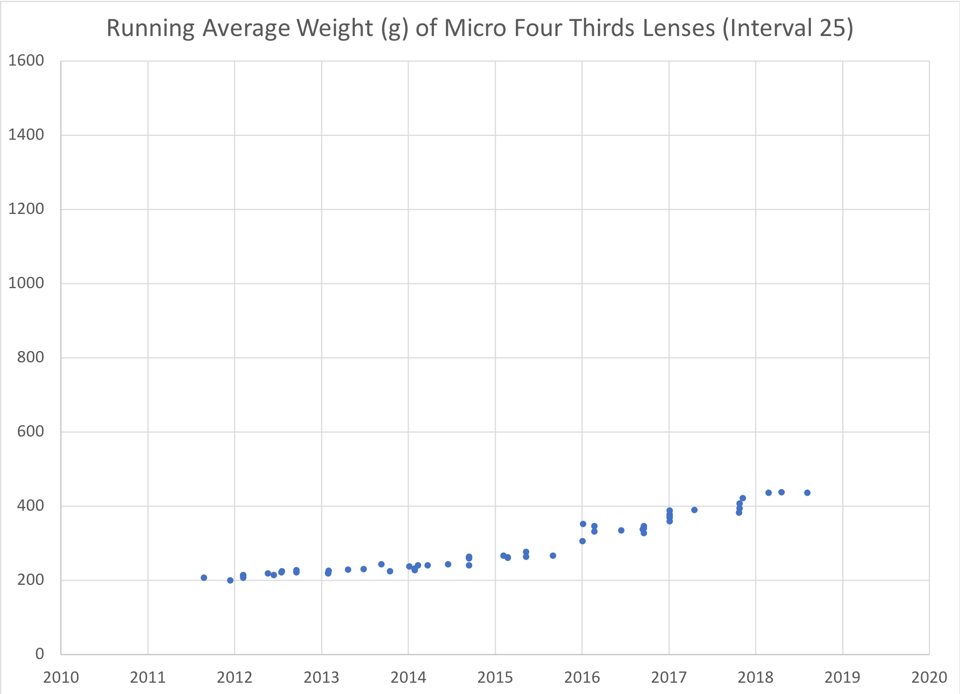

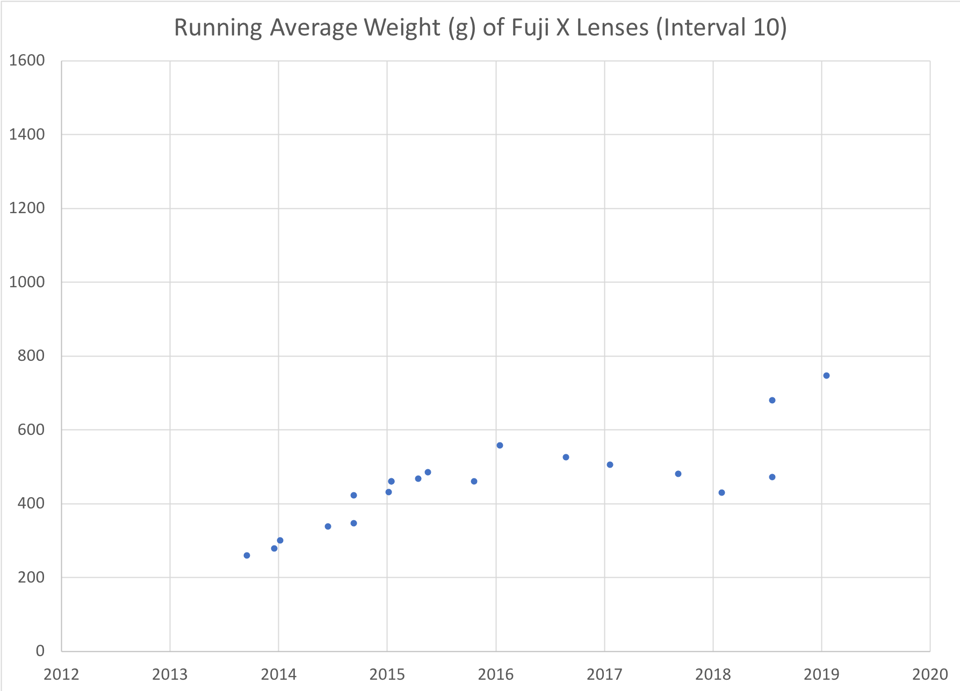

Granted, the graph above is a large-scale look at things rather than a specific analysis of mirrorless vs DSLR lens weights, or of certain weight classes (like supertelephotos, which have gone down in weight over time). But even the dedicated mirrorless companies haven’t exactly been trending in the direction of pancake lenses:

I am, in theory, a prime lens shooter at heart. I like light weight and high quality, and I don’t mind changing lenses. Yet my current kit consists of three zooms – a 14-30mm f/4, 24-70mm f/4, and 70-200mm f/4.

That’s because, amazingly, this kit is among the lightest possible ways to cover the focal lengths from 14mm to 200mm without any huge gaps in between. The zooms weigh less than the primes.

Where are the f/4 prime lenses? Frankly, where are the f/2.8 prime lenses?

Other than specialty lenses like macro and supertelephoto options, very few lenses from major companies are f/2.8 primes, let alone f/4 or smaller.

Prime lenses have two major advantages over zooms, at least in theory: wider apertures and lighter weights. Lens manufactures have almost entirely ignored the second benefit in favor of the first.

The closest we’ve gotten are f/1.8 primes rather than f/1.4 or f/1.2. And although those are nowhere near pancakes, they still have some pretty awesome benefits. For example, the Nikon 35mm f/1.8G FX is at least as sharp as the Nikon 35mm f/1.4G, yet weighs half as much (305 grams vs 600 grams). And that’s the difference between f/1.4 and f/1.8 – not even a full stop of light.

What would a 35mm f/2.8 lens look like? One of the few 35mm f/2.8 lenses on the market right now is a Samyang autofocus lens for the Sony E mount. It weighs 85.6 grams (literally three ounces), costs $270, and gets very good reviews.

So: extremely light weight, good reviews, and a very reasonable price. This is also an f/2.8 lens we’re talking about – letting in just as much light as the most expensive 24-70mm f/2.8 zooms.

Why are there not dozens of lenses like this, from more prominent manufacturers?

If you’re wondering what a 35mm f/4 lens would look like, unfortunately you’ll need to keep guessing. There currently is not such a lens offered by any manufacturer. However, I suspect that such a lens would be able to match the weight of the Samyang 35mm f/2.8 with even better image quality – a true high-quality pancake prime.

I know that a lot of photographers need a wider maximum aperture than f/4, or wider than f/2.8. But the proliferation of f/4 zooms suggests that many photographers just don’t.

Personally, as someone who almost entirely shoots landscapes, I wouldn’t mind if my lenses had a maximum aperture of f/5.6! Pretty much the only time I need anything wider than that is for Milky Way work.

I’d jump at the chance to buy a kit that looks something like this for landscape photography: 16mm f/2.8, 24mm f/4, 35mm f/4, 50mm f/4, 70-200mm f/5.6. (The last one is a zoom because, with telephotos, you can only go so “pancake,” and zooms definitely do save weight.) Based on existing lenses, my estimate is that this combo would weigh about 1150 grams, or 2.5 pounds.

By comparison, the current zoom kit that I use – 14-30mm f/4, 24-70mm f/4, 70-200mm f/4 (adapted) – weighs 1970 grams (4.3 pounds). And that’s a light kit. It doesn’t even go to f/2.8 at the wide end. Many photographers use a 14-24mm f/2.8 instead of an f/4 zoom, or even a 70-200mm f/2.8 for their telephoto. That easily puts you in backbreaking territory.

The Tamron 15-30mm f/2.8 weighs a whopping 1100 grams (2.4 pounds)

At the moment, the only company that’s doing even a halfhearted effort at releasing pancake lenses is Samyang, unless you count all the old Leica lenses designed with a lightweight philosophy in mind. You might think Fuji is doing well in lens weight, but their running average weight of new lenses has actually increased more quickly than any other camera company (about 300 grams in 2014 to about 700 grams today).

The worst offender in total weight, though, is one of the rising stars of lens design: Sigma. Their new 40mm f/1.4 Art lens is, I’m sure, an absolute image quality beast. It also weighs 1200 grams – more than the entire hypothetical kit of pancake lenses that I listed above.

Surely I’m wrong about the potential of pancake lenses to take over the market, even for mirrorless users. There’s no way so many different companies have had such a large blindspot in their lens lineups for so long – and, beyond that, are doubling down on the strategy of increasing weight. Right?

Yet… you have to wonder. By using a smaller maximum aperture, lens manufactures could cut weight (and price) without losing image quality. Would you rather pay $1400 for a 28mm f/1.4 that weighs 900 grams, or $400 for a 28mm f/2.8 that weighs 250 grams – same image quality?

I know my answer. The first lens company to release a comprehensive line of high-quality pancake primes will also be the next one to get my money. But that doesn’t look like it’s going to happen any time soon.

Lens manufacturers don’t want their gear to fall behind what other companies release, so their designs get more complex over time. Online reviews perpetuate the cycle, because sites like ours want each lens to be sharper and brighter than the one before. And thus, weight increases, especially in primes.

But these days, it’s not even that zooms weigh less than a comparable set of lightweight primes. It’s that there is no set of comparable lightweight primes, period. To me, that seems very much at odds with the lightweight mirrorless strategies being pushed at full speed by so many camera companies today. But it certainly appears to be the direction we are headed.

I’m traveling at the moment and cannot respond to every comment. However, I will read each one and respond to any questions when possible. Thanks! -Spencer

It seems like there’s so much time needed for releasing lenses with these big companies that they just dont put out many plus there ultimate sharpness, or bokeh, lightweight or different mm or should we release a zoom or prime, something special ex macro etc its almost as if there’s too many possibilities too fulfill them all

I did bought Samyang 35mm f/2.8 just because is light and pancake. I love it because it is light. I do use old Minolta AF 50mm f/1.4 and Minolta AF 135mm f/2.8 as they are good and light even when I use adapter. I have Sony 24-105 f/4 G lens which does a lot of work but is not exactly light -650gr. So I do agree with the review.

This makes so much sense for landscape and travel (ha) well put together, I’ve just ordered the Nikon Z7ii and my old Nikon primes weight a ton in my Shimoda action 50 backpack. Why has only Samyang tried addressing this obvious gap in the market. Doh

Nikon has had 28mm and 40mm pancake (compact) primes on their roadmap since about the beginning (and a 50mm micro [macro]) but still no date announced. These are non-S lenses and should be slower and smaller (and cheaper). I think that’s a plus. What are they waiting for? I would love to have small primes for my Z system for casual shooting and travel.

Great article, Spencer. When I went in search of a 35mm prime for my recently acquired D750, I could not believe the size, weight and COST of the latest and greatest Sigma, especially when my 50 mm f1.8 nikkor provided change out of $200 and was tiny, and my Fuji f1.4 35 mm was only a little more. I ended up with a nikkor f 1.8 G and a nikkor 85mm f1.8 D for less money. Both are superb. Nikon has so many superb D lenses which really shame these grotesque Sigmas. Yes they are older designs, but they work beautifully.

Two pancakes planned, 28mm and 40mm…

www.nikonusa.com/Image…ansion.pdf

There is no escaping the laws of Physics…

What might Galen Rowell’s mirrorless kit look like? As a climber/mt. biker/kiter with tweaks and injuries to contend with, I need more speed in my body – less in my lenses. Light is right in the mountains. I’m with Spenser 100%.

Spencer,

Thanks for your insight and thoughts. You did put a big smile on my face when you specified your ‘kit’. I expected something like a D850++++. To my surprise, your kit is my kit! I have sold off my DSLR and some lenses– and gone over to the Z6 and the three lenses. I ‘travel’ with my Peak Design 5L with the 14-30 and 24-70. What a pleasure! Thank you for being such a great asset to my photography life.

Just a thought: if you would fine with f/4 – f/5.6 prime lenses on FF which don’t currently exist, you would be fine with equivalent f/2 or f/2.8 lenses on MFT, which do exist.

Fully agree with both of your statements, Vlad. It appears, the camera has to be a SUV, but for the parking space of a bicycle.