About four years ago, I came up with a simple goal: photograph 5000 species of birds. How did I even think of such a plan? It all began with two questions: What is that bird over there? How is that bird related to the others? Soon, I started keeping track of all the birds I had seen, and specifically, photographed (that’s how I started identifying them). Before long, I started getting more obsessed with their classification, which opened up a whole can of worms.

Table of Contents

How Are Birds Classified?

There’s a special, delicate moment when a person sees a bird and figures out its name for the first time. It is almost as if learning the name of the bird confers the title birder upon the observer, like a spell being unknowingly cast upon reading a magical text. Pretty soon after, the names of all birds must be known. Their names, and the relationships between the different species, become central forces to grow the birder’s previously hidden seed of scientific curiosity.

These relationships are encapsulated in this basic hierarchical structure set forth immortally by Carl Linnaeus:

In it, all the world’s birds form a single class: Aves, containing almost 11,000 species. Then, the class Aves is divided into forty-two orders. Some of these orders have very few bird species, like the new world Vultures (Cathartiformes), consisting of merely seven species. There are even a few orders with just one species, like Opisthocomidae (with only the Hoatzin of the Amazon) or Leptosomiformes (with the lonely Cuckoo-Roller of Madagascar)!

But most other orders contain many more species. You’ve probably seen a duck before, right? They are part of the order Anseriformes of ducks and geese, and there are 178 of those. Or what about the Parrots and Cockatoos, in the order Psittaciformes? I consider myself lucky, having seen over 30 species of them, but that’s less than 10% of the total 390!

Then there’s my first bird, which was probably the first for many: the Rock Pigeon, which is actually an invasive species in most parts of the world. It is just one species in the order Columbiformes that contains 353 species.

But by far the most populous order by species is the Passeriformes. It’s famous for the many little brown things that hop around in the forest, eluding identification from birders who spend hours poring over the bird identification guides. Yeah, let’s talk about those.

The Passeriformes or Passerines

The order Passeriformes dwarfs all other orders with about 6,500 birds, which is more than ten times the number of birds in the next most populous order Caprimulgiformes. What’s the deal with these things?

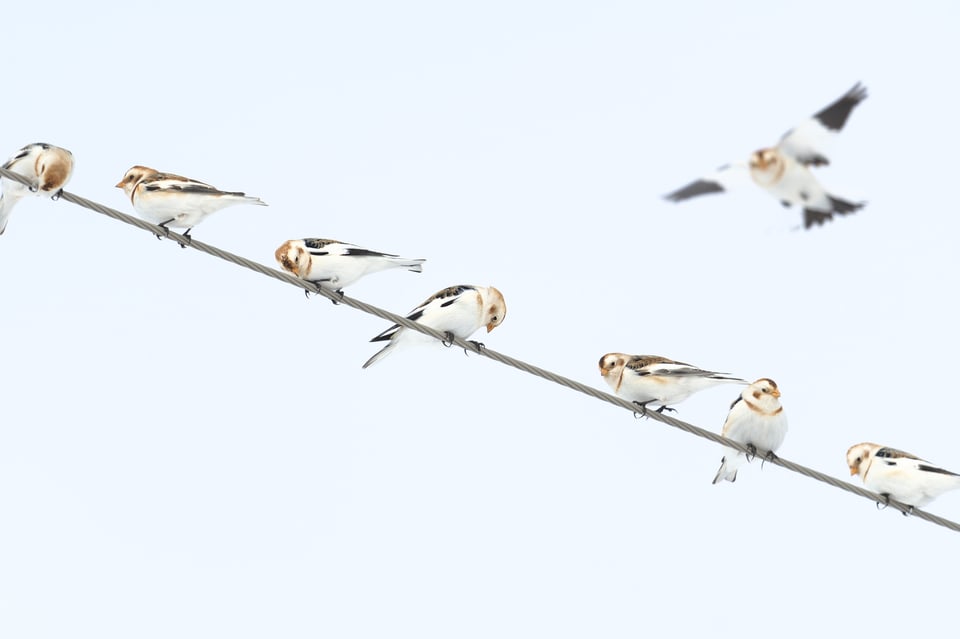

Birds in the order Passeriformes are typically called “passerines.” Both words come from the Latin “passer,” which means sparrow. But what is a passerine? As the name suggests, passerines are typically smaller birds that perch. They are sometimes also called perching birds, even though, of course, some non-passerine birds perch, too!

The vast majority of Passerines form the suborder Passeri, also known as oscine or songbirds. Although all birds make calls of some kind, the songbirds have the most complex and pretty songs. Many of them can invent new songs throughout life and learn a variety of beautiful melodies. The songs of birds has been entrenched in all forms of art. Robert Frost once wrote, “There is a singer everyone has heard,// Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird…”

Passerine birds are typically smaller than non-passerines. It’s not a perfect rule – there are some very large passerine birds such as ravens, and some small non-passerines such as crakes. However, as a rule, non-passerine birds are larger and more noticeable. In fact, the top five birds photographed on eBird are all non-passerines: Red-tailed Hawk, Great Blue Heron, Mallard, Bald Eagle, and Great Egret.

The photos for these five on eBird recently passed two million, and there must be many more photos of them that people never published online. On the other hand, many non-passerines are still very rare. As yet, there isn’t a single photo on eBird of the Sira Curassow, a critically-endangered non-passerine bird with around a hundred individuals remaining in the Cerros del Sira mountain range of Peru.

But the natural question is, why are there so many passerine birds? Actually, the answer to that question is not altogether straightforward. Some researchers in the past have even chalked the answer up to a coincidence of classification. Biologist Storrs Olson gives a convincing hint, saying that:

[it may be] the ability of passerines to move into new environments as a key factor in the success of the order. If there is any single attribute that would make this possible, it is the ability of passerines to adapt their breeding regimen to locally available nest sites and nesting materials. The brain in the entire order appears to be “hard-wired” for nest-building inventiveness.

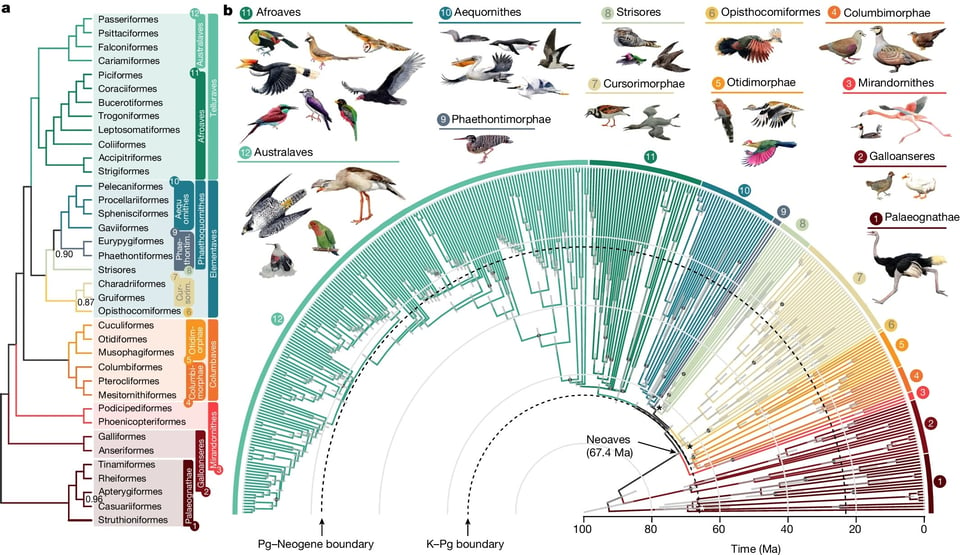

One can see this impressive radiation of the passerines and indeed all birds in this cladogram, which can be taken as a rough approximation to the evolution of birds, with the passerine birds taking up the entire left half of the semicircular chart:

Inevitably this means that I come across many passerines as a wildlife photographer, especially on my journey to photograph 5000 different species of birds. But as you can see from the cladogram above, classifications do not stop at orders. The classification is further divided into family, genus, and individual species of birds.

Families of Birds

Each of the orders is divided up into families, and each family consists of a number of genera, each with one or more species in it. When you hear about a common “group” of birds like Kingfishers, Hummingbirds, and Herons and Egrets, it is typically families that you are hearing about.

The families are perhaps the most intuitive, because they correspond readily to similar body types (morphologies) among birds. Any two hummingbirds look quite similar in shape, and so do any two herons… more or less, at least.

Although I’ll spare you too many more details of bird classification, for someone like myself, I enjoy exploring it immensely. And that’s not just because it’s a cool scientific topic, but also because it helps me understand birds and bird behavior better, which is great for understanding how to photograph them.

And of course, it helps me identify them more easily. If a bird looks like some kind of gull, I know where to look in an identification guide, at least. Almost all guides are grouped by bird families to make for quicker identification.

Photographing 5000 Birds

Have you ever seen the author bio at the bottom of my articles? It says that one of my life goals is to find and photograph 5000 birds. Of course, I was immediately attracted to bird photography from the first shot I took, but the idea of photographing 5000 birds crystalized before I really even understood my underlying motivations.

Maybe the number 5000 seems arbitrary, but I chose this number with the idea that seeing about half of the world’s birds would be a lot more doable than seeing all of them. That would be especially true if the half I saw was the easy half (although some of them definitely have not been very easy).

On the other hand, there is some sort of metaphor to the number as well. I feel that it is a partial distillation of an ideal: to spend as much time out with the birds, and indeed all animals, as possible. It is not realistic to see 5000 birds in just a year or two – rather, it’s a commitment of many years or even decades. And this commitment is not just a way to become a better photographer, but to understand what is going on in the natural world, gaining knowledge that cannot be learned through other means.

I also felt that I didn’t want this search to become a twitching contest simply to see more species. I would rather temper the idea a bit, take my time, and enjoy the experience. Hence why my goal is 5000 rather than anything approaching the (currently) 10,826 birds on eBird’s list. To me, getting good sightings, savoring moments, and taking the entire process slowly is much more important than building a collection.

In that sense, it’s not really important if I ever reach 5000 birds. I like seeing new species, and I’ve photographed 743 of them.

Not all of them are great photos, and perhaps that’s another reason why I choose 5000 instead of every bird: I’d rather go back and get better shots of species whose photos didn’t turn out, than go after a new species. I have been known to completely ignore unfamiliar bird calls in the distance if I spot a good photo opportunity of a Rock Pigeon nearby.

Parting Thoughts

When I first started exploring my interesting in photography and birds, I was a professional research mathematician. Often during my times at my old job, I used to look out the window. In the winter, I especially remember the peaceful scenes of American Crows playing, flying, swooping from the roof, chasing each other. Against the background of the blinding white snow, it seemed that the world of the crows was another dimension, a dimension that I was observing but not part of. I would often ask myself, why aren’t I out there with them?

The desire to chase birds was getting stronger, and research mathematics lost all its original appeal. And why not 5000? So, the soonest I could, I quit my job, and now I am in their world. I know it’s the right place for me to be.

Hi Jason, Thanks for the great article! Well, 5000, is a big number and a few years back I met a British birder (no photographer) and it took him 35 years to reach that number! Having a goal is a good thing, realistic or unrealistic is subject for debate. At my end, my driver is not the number itself, but rather managing to have decent, acceptable images, is what counts! Of course, on an off, I too look at my number, which is just shy 5 of 1500 ;-)

Thank you for the comment, Frank. Hey 1500 is great. To tell you the truth, I am absolutely happy if I never reach 5000. I just want to spend my days out in nature, watching birds, being with animals under the trees and in the deserts and whatever other environments I can find. The best part is not even the photography. Photography is more of a way to hold onto those moments when I’m not there.

fantastic article Jason. You’ve inspired me to quit my job and chase my dream. I’m jk haha but I do hope to follow what you did someday soon

That is very kind of you, Loi!

“It is not realistic to see 5000 birds in just a year or two – rather, it’s a commitment of many years or even decades.”

Well, it actually is, although not without ultimate dedication. Noah Strycker targeted 5000 in one year in 2015 and ended up with over 6000, one year later Arjan Dwarshuis got close to 7000…

True, it’s definitely possible, especially if you have a lot of resources. Getting good photos of each one would be difficult even with unlimited resources though.

I agree, it’s definitely also a matter of ressources… Anyway, I’d rather spend some more time with each species, than racing through 5000+ in one year!

Do you find that immediately you seek to measure something, you change your behaviour?

For e.g. I set myself a target to read 100 books a year. But of course not all books are equal. The target can influence my behaviour by suggesting that I read 2 400 page books rather than one 800. (I have some very long books). I read mostly non-fiction so not many are ‘rattling reads’ (but then neither is anything written before 1900, fiction or otherwise, imho).

I don’t tire of photographing, say, swans because I’ve photographed quite a few. Better have a good photo of something I’ve photographed than a poor one of something new?

(I achieved 100 for a few years and then abandoned it.)

(As a (former) mathematician, please don’t suggest that I reframe my target in pages and that I record pages read … then we’d get into fonts and line spacing be down to words.)

Grief.

I’d no sooner posted this than I got an email from Substack saying …

… how many words I’d read on it.

Aargh!

Your comment made me laugh (about the pages vs number of books – I relate to this too much)! You bring up an interesting question though. For me, I do find that setting measurable goals influences my behavior, both positively and negatively. For example, with your book scenario, setting the 100 book goal would indeed make me more likely to read shorter books, but it also would encourage me to read at times where I otherwise might not. So for me personally, I do like to set goals carefully knowing both the positive and sometimes negative impacts that can have.

One other thing I would mention – I think timeframe of goals makes a big difference. If I have a goal that needs to be completed this week, it will have a very strong impact on my daily behavior. If I set a lifetime goal (like Jason is in this article), I think the timeframe gives a lot of room to not focus too much on getting “the next bird”.

Interesting question…I have to admit, not. My brain does not seem to be compatible with setting actual numerical goals. The 5000 was more of loose, airy concept, and I don’t have much fun when I’m just aiming for numbers most of the time. As for reading in terms of pages, well a better solution is to count characters since most lines have the same number of characters and most pages have the same number of lines…hhahaha

Wow, 5k bird species is a huge goal!! In Australia, we have less than1k species. I only started bird photography in my mid-40’s so ‘d be surprised if I get to see all the Australian species in my lifetime.

Have you read the Big Twitch by Sean Dooley? It’s a fun read about Australian birding. Not sure if you noticed but I included an Australian bird in the article – Singing Honeyeater. I started birding there and got up to 297 species. Orange-bellied Parrot, Beach Stone-Curlew, Gang-Gang and other Cockatoos are some of my favourite memories :)

Hi Jason,

My lifelong goal is similar to yours, except it was to see at least 50% of the world’s birds. I’ve been birding for 50+ years and I am within 100 species of 5000! As the avian phylogeny experts keep splitting species, that goal is now closer to 5500.

I’m also planning on photographing a quarter of them given my later start with photography.

How do you plan on keeping track of your goals? I gave up on home-made spreadsheets or custom software, and find eBird to be ideal. Cornell benefit from all these observations and media records and I get to share my photos. I’ve added about 7k images representing over 1300 species.

Jim in Austin, TX

That is TRULY amazing, Jim. Wow, so close to 5000. Incredible. Do you think it will be hard to get those next 100? I’d imagine so. Congratulations, though. You must have amazing memories of some incredible birds.

I do use spreadsheets but as a backup to eBird. Like you said, it’s just much easier, and they keep track of species splits as well!

I love this, Jason! I enjoyed the insight into bird identification, and also the insight into how you approach things in life. It feels like the world today, especially social media, really enables the tendency to be aimless if we aren’t careful. Having a goal like yours is a bulwark against that.

I really do appreciate those words, Spencer. It is indeed quite an easy thing to engage in goal-directed behaviour, spurred on by high-speed communication, and forget to slow down a bit.