Even though my first camera was the digital Nikon D5100, I always have felt a sort of secondhand nostalgia for the days of film photography. The vast majority of history’s great photographs were taken on film; masters like Ansel Adams and Galen Rowell defined the medium of landscape photography in my mind, and both were entirely film photographers. Personally, by using a digital camera so early, I felt that I was missing a more hands-on appreciation for photography’s complex history. Perhaps this thought was not first on my mind while in the field, but it certainly surfaced from time to time.

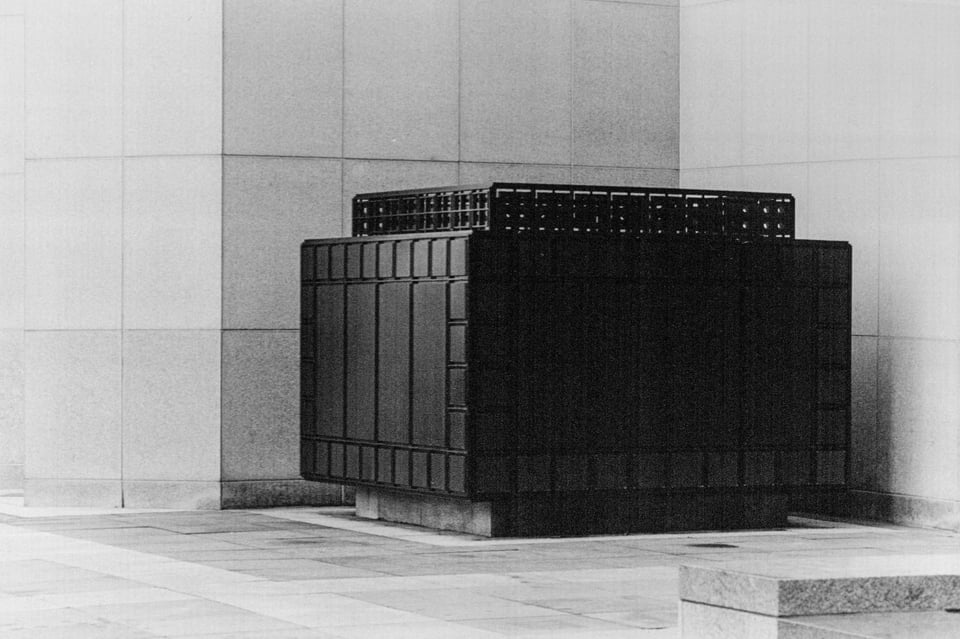

For that reason, I was thrilled to have a chance to shoot traditional, darkroom-based black and white photography throughout the past three months. I used the Nikon F100, since it works with all of my modern lenses (including vibration reduction and autofocus), along with Tri-X ASA 400 monochromatic film.

Table of Contents

Choosing Subjects Carefully

With 35mm film, you only get a few dozen photographs per roll. As a digital photographer, I have gotten into the habit of taking a handful of photographs for every subject, testing different compositions and making sure that my settings are as accurate as possible. Not so with film.

Shooting on the F100, I found myself spending far more time on every photograph than typical. Sometimes, I wouldn’t even take a photograph that I had started framing – even if I already spent more than a minute on my composition. Film isn’t hugely expensive (roughly fifteen cents per frame, not counting development costs), but you only get a handful of photos per roll. I also had just ten rolls, and they needed to last me three months (which is how long I had access to a darkroom).

All of this meant that I had to choose my subjects very carefully, and I had to visualize how each photograph would look as a print. This was valuable – and I’m sure that it improved my compositions – but it also took a lot of time. Honestly, that was the main difference for me between film and digital; film takes far more time to shoot.

Lack of Instant Feedback

Before I bought the F100, I felt fairly certain that the most difficult part about film photography would be the lack of feedback. I love my digital camera’s LCD screen; as a landscape photographer, I shoot in live view mode at least as much as through the viewfinder. I also rely heavily on the Image Review mode in order to check my focus, composition, and other settings. None of this, of course, is possible with a film camera.

In the end, though – despite occasionally checking the back of my F100 in a failed attempt to review a photo – this was not as difficult as I had expected. There certainly were times when I would have wanted to review my shots, but not particularly often. I credit this to the care that I had to take with every film photograph; I simply checked my framing in the viewfinder rather than on an LCD screen.

At the same time, I know that the lack of instant feedback would have made it difficult to begin photography with a film camera. If I had not been shooting digital for several years, I wouldn’t have had a clue how to choose the proper shutter speeds and aperture settings. I can’t imagine the learning curve for film photographers, and I am quite glad that I began my journey with a digital camera; otherwise, I know it would have taken much longer to learn everything I know.

Seeing in Black and White

Tri-X film is black and white, which worried me initially. Although I love monochromatic photographs, most of my personal images are in color. When I do convert to black and white, I tend to spend quite a bit of time getting the tones and contrast correct; it is not something that I like to leave at the default values.

With Tri-X, of course, everything is at a “default” value; you don’t have nearly as much control over the conversion of a color world to black and white. Although it certainly is possible to use filters for this purpose, I did not purchase any, since I knew I would be shooting film for no more than a few months. So, for me, the F100 became an exercise in seeing the world as levels of light rather than colors and hues.

Luckily, I took many of my film images in downtown Chicago during the winter; there weren’t many bright colors in the first place, which made it easy to envision how a monochromatic image would appear. Still, at times, I found that a photo was significantly different than I expected – a yellow taxi losing its intensity, or nighttime scenes appearing more drab than they did in my viewfinder. I am sure that my monochromatic eye would improve over time, so these issues may only be relevant for beginning film photographers.

The Darkroom Process

I knew nothing about the darkroom prior to shooting film, and I am sure that some of our readers – although certainly not all – are in the same boat. The complex, mysterious concept that I had in mind was quite far from how darkrooms truly work; in reality, they are quite simple and ingenious.

First, you would need to develop your film. This process begins by opening a canister of film (which already has been shot, of course) in the dark, then winding it around specially-sized reels. The reels are placed in a light-tight container, where water (and other chemicals) can be poured.

Now, you can turn back on the lights. It then takes an hour to develop the film, which you do by pouring developer, fixer, and other chemicals into the container at specified intervals. It is not worth covering the specifics; this is a time-consuming process. Higher-tech machines exist for developing film, of course, but this is the method that I used.

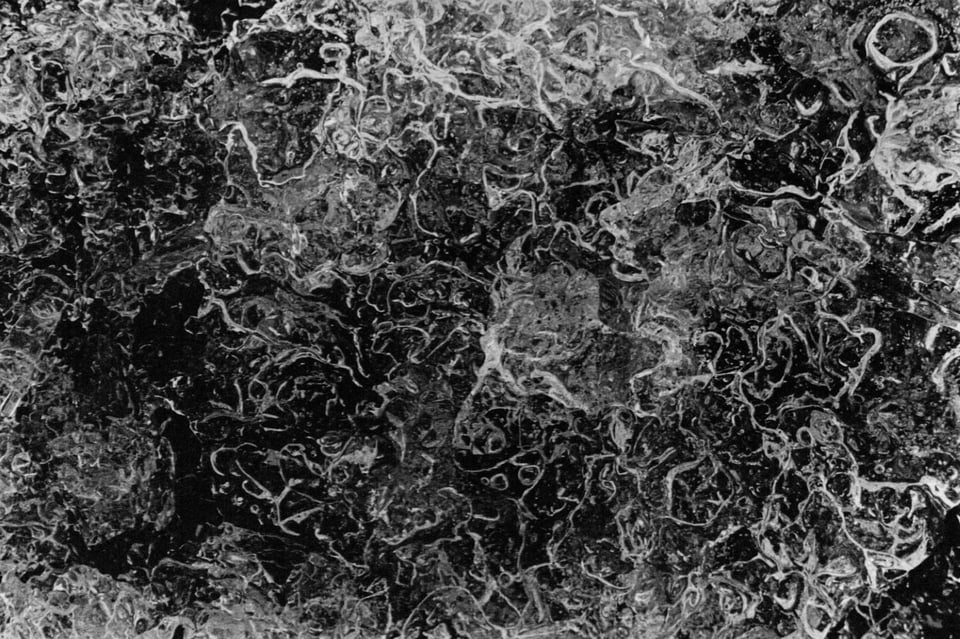

The fun part – and the true darkroom work – comes after the film is removed from its reel and then dried. At this point, you slide the film into an enlarger, which projects an inverted version of the photograph onto a sheet of light-sensitive paper. The longer the projection lasts, the darker your ultimate print will be. In the mean time, though, the paper stays pure white; you can’t yet see any differences between an exposed and a non-exposed sheet of paper. (Also, although the paper is sensitive to light, it only responds to certain wavelengths. This means – luckily – that you can turn on a dim, amber-colored lightbulb while you make your prints, and the paper is not affected.)

After exposing your paper, the next step is to place it into three different chemical baths: developer, stop bath, and fixer. The developer causes your image to form, which is quite fun to watch; you literally can watch the photograph appear before your eyes. Next, you put the paper into a stop bath, which halts the development process. Finally, place it into the fixer to ensure that your paper no longer is sensitive to light.

If you’re following along, these steps can be summarized in seven steps:

- Shoot a roll of film.

- In a pitch-black room, unload the film from its canister and place it in a special light-tight container. You can now turn on the lights again.

- Pour chemicals into the container, including developer and fixer.

- Unload and dry the film.

- Place the film into an enlarger, and make sure that the only light in the room is amber-colored.

- Put light-sensitive paper under the enlarger, then project your image onto the paper.

- Place the paper into developer, a stop bath, and fixer. Wash off the final print in water. Now, it is ready to display.

If all of this is familiar to you, my apologies. However, I hope that some digital-only readers now have a better sense of the darkroom process (at its simplest, that is – there are many ways to make these steps more involved). It certainly was exciting for me, and I honestly enjoyed this sort of hands-on style of photography – even though it was so time-consuming.

Accepting Imperfections

Perhaps the biggest lesson that I learned from film photography was to accept that there is no way to make every photograph look perfect. With digital, I constantly struggle with this; an image is never “good enough,” and I always see a number of ways to make every photograph better. Unfortunately, despite the plethora of digital edits that I can make, there never is a truly “finished” state; a month later, I will look back at the photo and see dozens of new changes to make.

Film is this same feeling, but magnified. Every time that I needed to change a small aspect of a print in the darkroom, I needed a new sheet of paper and fifteen minutes of processing. If my horizons were crooked or my framing was wrong, I could only go so far to fix the mistakes. Given unlimited time and paper, I certainly could have made more edits – but even then, my darkroom skills would not come close to replicating the post-processing that is possible on a computer.

In the end, I had to accept the imperfections of my prints – which was a good thing. As I took more and more pictures, I became less interested in technical perfection and more interested in lighting, composition, and timing. Since I knew that the photos weren’t going to look “perfect,” I didn’t try to attain an impossible level of precision. Once I understood the limitations of film (and the general darkroom process), I started to feel more comfortable displaying photos that were slightly different from what I wanted. This same mindset can be equally valuable for digital photography; it is rarely worthwhile to spend hours correcting the nearly-invisible errors in your images (although I find myself doing so all the time).

Conclusion

Although I certainly am not planning to swap my digital camera for a film setup, I learned quite a few valuable lessons from my time with film photography. More than anything, I found my visualization skills improving; I had to “see” the world as it would appear in my final print, which helped me spot the scenes that would make high-quality photographs.

On top of that, I thoroughly enjoyed learning about darkroom techniques. It is easier to understand the impact that Ansel Adams had on photography – revolutionizing exposure and the darkroom process – now that I have begun employing some of his methods myself. Film was far more tangible than digital photography; I saw every behind-the-scenes step of a photograph’s creation, and it made me appreciate the complexity of photography from a different perspective. If you have shot film and created darkroom prints before, I am sure that you would agree – and if you haven’t, I absolutely recommend trying film if you ever have the opportunity.

I wish I still had my Nikon FM2s and the 50/1.4 and 105/2.5…but alas. I wonder about getting another Nikon film camera and then scanning the negatives or slides. I really loved those two lenses and simply can not afford a comparable AF on a new Nikon. My only question is obtaining film (no camera store where I live) and getting good processing (all my stuff is gone). I was always a low ISO user (Ilford Pan F and Agfachrome). Comments?

General use Kodak and Fujifilm film is available at many local drug stores. Many kinds of film are available on the internet. Film processing is also available on the internet and may be available locally, but not everywhere.

Thanks for a great articel. Like you, I discovered film after digital. These days, I use both. Even with digital I am a slow photographer so i don’t mind the time it takes to take a picture with film, as a matter of fact I enjoy it. When shooting film I use a hybrid workflow where I develop my own films (I use a Jobo processor which cuts time and helps with maintaining the proper temperature), and then I scan the negatives.

One thing that I enjoy with film is the old gear: SLRs without any metering/focusing aids, manual focus with center-weighted metering, the last Canon or Nikon pro SLRs that have more sophistication than some DSLRs today, TLRs, rangefinders, compacts, all these can be had for very cheap, and each of these cameras has its personality, and you have to learn their strong points and limits.

I am an amateur, I shoot 100% for pleasure. I like the results I get with my digital camera, but a good shot with film, nothing compares with that. More effort gives a more intense feeling of reward.

I really enjoyed the article. I myself prefer film to digital, because it seems I can control the settings easier. With the digital camera I have it’s point, shoot, and everything is automatic. With the old school film camera I have everything manual from shutter speed, to aperture, to zoom, focus, depth of field. I enjoy tinkering with different settings to get amazing effects, or crisp photos. Overall give me the old stuff. I don’t have to worry about a battery going dead, or running out of space on an SD card in the middle of a shoot. It just seems more reliable, especially when hiking in the back country looking for that one exquisite waterfall or a tiny baby deer hidden in the grass.

Spencer, thanks for an interesting article. Ultimately for most of us photography is a hobby to be enjoyed whatever tools we use to produce our images. I’m lucky enough to own a both a Canon 5DSR and Fuji X100T. That being said, every so often I can’t resist picking up my Nikon FM3A and running a few rolls of film through it. For no other reason than I enjoy using it. Its not better or worse than digital, just different.

Looks like your sensor has poor dynamic range and suffers from pretty heavy chromatic noise :-)

I had not seen your article and only read it after coming back from a walk carrying my Konica Hexar loaded with Fuji Provia 100F… Love old tech now and then, forces me to slow down and concentrate on a handful of shots. I don’t shoot more than 5% that way but it is a nice breather when I do. It was just serendipity that it should be today.

Enjoy the experience and don’t sniff the chemicals.

Thank you, Frederic!

Hey Spencer,

What a nice surprise to see you got your hands on an F100 and some Tri-X! I enjoyed the article and had many of the same experiences myself. Hopefully this isn’t the end of your film days. Even if you don’t have access to a darkroom, you can always send film off to a lab to be developed and scanned. Let me know if you need any recommendations.

Best!

John

Thanks, John! I do know of some good labs nearby, so I’ll probably shoot a roll or two from time to time. Nothing like the darkroom experience, though :)

I’m glad to see some film work on Photography Life. While I haven’t been doing any for the past couple of years, I did a good deal of B&W film shooting about 4-7 years ago on both 35mm and medium format. Given the vintage of equipment I used, all were manual focus and most were manual exposure. Many did not have a built-in light meter either. The variety of home-made pinhole cameras (these aren’t your basic pinholes, but fairly advanced ones) did not even have any sort of viewfinder for framing.

While I don’t choose film as my primary platform, I highly recommend the experience to force more thought into various aspects of one’s work. Particularly the use of cameras with more technical limitations like full manual and/or no light meter. It’s great practice and good fun IMO. For the hardcore enthusiasts or pros who have enjoy building, I highly recommend building your own pinhole cameras – nice ones, not the old oatmeal container with a sheet of photographic paper. :)

The images here, however, are a bit off. Something in your process has caused notable vertical banding and the sharpness is not what I would expect to see. How are you digitizing these? Did you scan negatives? Scan prints? Did you rely on autofocus or manual focus?

Brad, There are many excellent film photography articles on Photography Life:

photographylife.com/tag/film

Yes, the images in this article have those annoying bands — wish that I could fix them, but I don’t have access to a better scanner at present. I’ll scan the prints more professionally when I have the chance.

“have felt a sort of secondhand nostalgia for the days of film photography.”

are you not like 16 y.o or something?

I’m 19. By “secondhand,” I only meant that I had not shot film, but the stories and experiences of other photographers had worn off on me.

oh, that’s what you meant by ‘secondhand’. ok, i get it, sorry.

Vicarious.

Hi Spencer,

I love it when photographers shoot film for the first time and see the magic. Because it’s not about whether film is better than digital – it’s about the alchemy of the process.

I’ve been shooting since the 1980s and one of my oldest “friends” is a 1996 Nikon FM2 with its fast, new Voigtlander 58mm. Now I am a newspaper travel editor and shoot only digital for work using my Fuji X-Pro 1 and a fast zoom. The Nikon doesn’t get out much these days.

And here’s the thing: I had begun to hate taking pictures. Of course that has much to do with the process – on press trips, you shoot what you can, when you can. I found I was beginning to “grab” pictures, rather than make them. I’d come back from a trip, choose the pics we needed for print and online slideshows (love that they are called “slideshows” when they have nothing to do with actual slides) and then delete – yes, delete – everything else, and format the card to make sure!

I was ready to sell my gear and quit photography.

A month ago I went on a weekend B&W film shooting and printing workshop. We shot one roll of film on the Saturday morning, developed it and printed contact sheets in the afternoon. On Sunday we spent the whole day in the darkroom, printing pictures. Dodging, burning, playing with exposure and filters. After a full day’s work I had five prints. Five. And I was entirely content.

The best part? Standing in the cool, quiet darkness, watching the images appear like ghosts out of blank canvas. Doing something with my hands, and taking the time to do it properly.

Now you can take your time with digital, and shoot one frame at a time, shooting with all the discipline of a film shooter, and there is still one thing digital photography will never give you, and that is the satisfaction of turning down the RPMs and making the picture yourself.

I will carry on shooting digital for work. But I shoot film for myself.

This is awesome, thanks for sharing. I love your “alchemy” comment — very true, and I suspect that is why I enjoyed shooting film so much.

Thanks for sharing! I really like it!!! Great blog!

Glad that you enjoyed it!