Scientific photography bridges the intersection between art and science. It combines what I love about photography with the process of discovery, truth-seeking, and documentation. The end goal is not just to understand the world around us but to depict our discoveries in an inspirational way.

Photography as a whole is incredibly vast. Photographers have the power to capture the essence of their surroundings through realism, or to take more artistic liberties with abstract photography. Even the same subject can be photographed in all these varieties of ways. Whether you try to reproduce reality faithfully, or deviate from it for your artistic purpose, is up to you.

In this article, I will explore the concept of scientific photography – a fusion of art and science that grants a photo a dual purpose, combining both artistic ingenuity and scientific merit. So, allow me to introduce some of the exciting ways that photography intertwines with the scientific domain.

Table of Contents

Using Cameras to Record Data

At the most basic side of things, scientists use cameras to capture data. Art may be the last thing on their minds as they use the camera to simply document findings or use the images to help digitally analyze their data. I recently had the realization that most of the research I’ve contributed to as an aspiring conservationist and a marine science student involved photography.

Wildlife is secretive, and some species can only be studied using trail cameras to monitor their movements. Remote camera traps are crucial for the work of many wildlife biologists. Similarly, some marine biologists use baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVs) to study marine wildlife. This is what I’ve spent the bulk of my summer working on. Although we are not too concerned by how artistically our fish footage turns out, it’s always pleasing when a clip is extra crisp.

Even research I have done on microplastics in seawater involved photography. In order to quantify the size and abundance of microplastics in the ocean, we dyed the plastics in our water samples with a fluorescent dye that only binds to plastic, then photographed the particles with a microscope under fluorescent lighting. From there, we used computer software to count and measure the quantity and size of microplastics in our sample by counting the number of bright pixels in the images.

Purely scientific photography – when the images have only data value and are not meant to have artistic value – happens in almost every scientific field. Okay… so what? Why is it so interesting if scientists use cameras to record data?

Despite photography’s inherent realism, photography remains an art form. Although scientists may use cameras solely as an objective data-gathering tool, the medium quickly transforms into something more subjective.

It’s this boundary that truly piques my curiosity. As we delve further, it becomes apparent that this article might lean more towards exploring the artistic aspects of photography rather than focusing solely on the scientific angle.

Photography as a Means of Science Communication

Beyond its scientific applications, photography is an integral part of science communication. By translating complex scientific concepts into visual narratives, photographers help bridge the gap between the scientific community and the public. Here are some historically noteworthy examples that come to mind.

Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley blew the world away with his detailed images of individual snowflakes in the late 19th century. He proved that all snowflakes have a unique crystal structure, while captivating the public with their visual appeal. Over his lifetime, he photographed thousands of snowflakes, hundreds of which are in scientific archives today.

Within the last year, we saw the wreckage of the Titanic replicated by a massive 3D scan. Combining 700,000 images and 16 terabytes of data, the deep-sea mapping company shed new light on the sunken ship. The project shows the wreck in its entirety for the first time in extreme detail, offering the public a glimpse of something never before seen.

About a year ago, NASA’s James Webb space telescope brought the wonders of the cosmos back to earth, capturing images of distant galaxies, nebulas, and planets. Photographs of outer space captured by the James Webb Space Telescope ignited curiosity and an interest in astronomy in its viewers across the globe.

National Geographic’s Joel Sartore has dedicated his craft to capturing the beauty of endangered species. His work not only raises awareness about the need for conservation but also elicits empathy for the plight of these creatures. In his creation of the “Photo Ark,” a collection of high-quality images of imperiled species, he forever safeguards the beauty of these species we may lose to extinction in our lifetimes.

Natural history museums across the globe are in the process of digitalizing millions of biological specimens. Through 3D scans, microscopy, and photography, the museums seek to digitally preserve their specimen collections. This way, all the data they carry with them will not be lost to degradation or natural disaster.

A lot of these examples have a theme of preservation and shedding light on the otherwise unseen. Although many of the above examples I gave were the products of specialized imaging equipment, not all scientific photography is so high-stakes.

Cameras have never been so accessible as they are today. I think a lot of people are doing their own scientific photography already. After all, isn’t the goal of many photographers also to shed light on the unseen in an attempt to preserve a moment?

Everyday “Scientific Photography”

I would argue a lot of wildlife photography falls under the scope of scientific photography. Especially when photographing rare or underrepresented species, the goal is often to reproduce the beauty of nature in a photo, while also showing how that animal lives.

The same can be said about most photography, by pros and everyday people. “I saw that!” are the words behind a lot of photography. And they are also the words behind a lot of science.

Photography allows us to preserve the world around us and how it looked in a given moment. That’s why I think that casual photography and scientific photography are not so different from each other.

Detouring from Reality

But photography is so much more than merely reproducing the world around us. To say so is reducing the immense amount of artistic ingenuity and creativity of photography. So far, I have mainly talked about photography as a tool for scientifically capturing the world around us. However, on the flip side, I could argue photography is entirely subjective.

Even a scientific, data-minded photo is still taken with the hand and eye of a human – or at most, a human controlling a robotic camera somewhere. There are a million ways to photograph the same subject, and scientists and photographers alike must choose what to include and exclude from the a frame.

Are we really being true to the scene when we photograph Yosemite and leave the 40 other tourists just out of frame? Or when we photograph that animal out of the car window keeping the asphalt and road signs out of sight?

And that’s not to mention all the creativity and artistic liberties that can be implemented in post-processing or while taking deliberately abstract, interpretive photos.

What all great photographs have in common, whether realistic or abstract, is that they strike a certain emotion in the viewer.

The Bottom Line

The great conundrum in photography is that is is both largely objective and largely subjective at once. On one hand, photography is often perceived as an objective tool for capturing reality – a moment frozen in time, faithfully recording what was in front of the lens. The camera is considered a reliable instrument, capable of capturing scenes with incredible detail and accuracy.

Yet, on the other hand, the subjectivity of the photographer is bound to seep into the process. Every photographer brings their own perspectives, experiences, and emotions to the act of capturing an image. From the moment of framing the shot to the choice of lighting, composition, and post-processing, the photographer’s artistic choices shape the final outcome.

It’s this juxtaposition of objectivity and subjectivity that makes photography such a fascinating art form that blurs the boundaries between reality and interpretation. While certain genres, such as documentary and scientific photography, strive for objectivity to convey an unbiased representation of truth, there is still a human element. And that human element only grows in other forms of photography, like fine art and creative photography.

Though we may try our best to categorize a photo as more artistic or more realistic, they overlap tremendously. Some of the most artistically meaningful photos I’ve seen were captured in the context of science, and some of the most interesting scientific records in the past century were created by photographers.

What is photography to you? Is it a more objective medium that reflects reality? A truly subjective artform made for interpretation? Or something in between or entirely different?

Nice shots!

I think there is one inherent level of objectivity in photography, and that is photography should at least transmit level of believability to the viewer that the photographer basically saw the scene in front of him or her.

In other words, if I show someone a photograph, and they had the magical ability to go back in time and stand beside you, they’d basically think — “yeah, that’s about right”. Sure, there might be some more contrast, vignetting to simulate how the eye is drawn to certain parts of the scene, some distortion, or a bit of tonal adjustments, but a photo has to convey the general sense of “being there”.

That is why long exposure, flash, sharpening, tone curves, lens corrections, etc. still are within the realm of photography. Even the smoothed water effect can sort of be imagined by the viewer as the process of the movement in the mind’s eye.

That’s why sky replacement and wholesale removal of major objects through generative fill in photoshop is no longer photography. That type of major edit violates the “yeah, it’s about what I saw” rule, a rule which I believe is the main essence of objectivity in photography. The rest is more or less subjective, I guess.

Interesting thoughts.

It strikes we that many scientific images are mostly “just” data until there is a *selection* of an image for artistic reasons. I’ve taken thousands of circular fisheye lens photos over the years (many different cameras and lenses) which were taken soley to get a couple of numbers to characterize a plant’s light environment. Sometimes when I’m reviewing the images, one pops out as just plain cool – as an image (sometimes those are images that aren’t useful for the data set). Maybe I ought’a make a collection of those. To me this looks like the genre of “found art”, where stuff found outside is picked up and displayed as art – some people despise that, I’ve always rather liked it.

And then there are the sort of images that you do, that document a critter in relation to its place – but by taste and craft is elevated to something well beyond documentary. I’d love to be able to accomplish that.

I am a geoscientist, and often take photos of rock exposures. These may be seen as aesthetically deficient because they always include scales and sometimes include color balancing elements n the photos. I’d post an example, but I don’t see an attachment widget on this page.

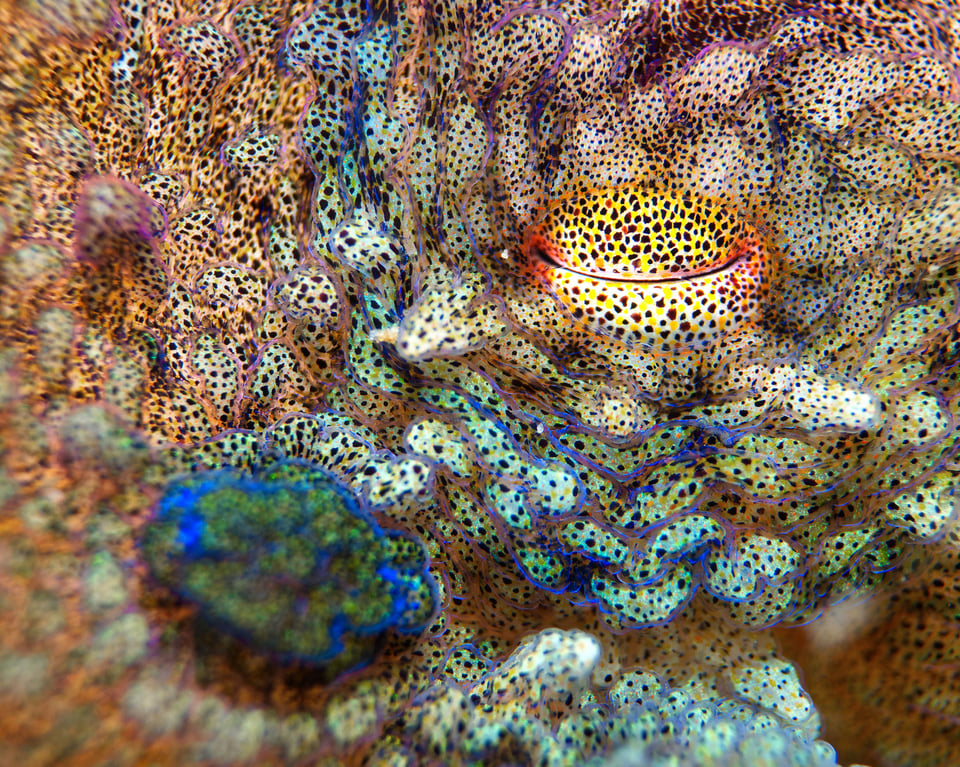

Stunning close-up photography. The detail is incredible and really makes you appreciate how unique each creature is.