The Olympus OM-D E-M5 mirrorless camera was released on February 7, 2012 right before the CP+ Camera and Photo Imaging show in Japan. Along with the camera, Olympus also released two lenses for the Micro Four Thirds mount – the 75mm f/1.8 and the 60mm f/2.8 Macro. The E-M5 generated a lot of buzz among the photography community when it was released, because of its impressive specifications, compact weather-sealed body and a beautiful retro-style design – all to satisfy the demanding needs of the enthusiast and professional crowd. Within a relatively short period of time, the camera became a huge success, thanks to raving reviews from respected photographers.

I did not pay much attention to the E-M5 at the time, because I was too busy with the Nikon D800/D800E announcements and tests. However, I really wanted to check it out sometime later, after all the dust settles. Summer and Fall were very busy seasons for me professionally, so I had to postpone my plans even more. The camera finally arrived in mid-November, along with a bunch of other mirrorless cameras from Sony, Nikon and Canon. It only took me a week with the E-M5 to realize that it was exactly the camera I had been longing for.

While I love my Nikon DSLRs for serious and professional work, they are just too heavy and bulky to carry around for those everyday moments. If you own a full-frame DSLR with a professional lens, you know exactly what I mean by this. I was just getting tired of missing great moments just because I left my huge “professional” camera at home. Sometimes those precious moments happen everywhere – in a store, on the street, while driving a car. Yes, my iPhone sometimes can be handy in those situations, but what am I going to do with those images aside from putting some crappy Instagram filters on them just to make them look better? I know I won’t ever be printing those. So I had been wanting to get something between my phone camera and a DSLR, with a condition that it is small, has amazing image quality, great lenses and a working autofocus system.

The Olympus OM-D E-M5 easily fit those requirements and it clearly stood out from the crowd of all mirrorless offerings. While many other mirrorless systems had great features, they all lacked something important or had serious drawbacks. The Fuji X-Pro 1 is amazing, but its terrible RAW support from Adobe, comparably weak AF system and high price were the reason I dropped it as an option. The Nikon 1 cameras have an amazing AF system, but the small sensor, lack of good lenses and a few other annoyances like proprietary flash shoe also dropped them as an option for me (although I must admit, I almost bought the Nikon 1 V1 when its price dropped to $299). The Sony NEX cameras were amazing, especially the Sony NEX-6 that I absolutely loved, but the lenses were just too big and bulky for my taste. And the Canon EOS M is not even in the same class to look at it as a serious option…

After my wife Lola took the Olympus OM-D E-M5 for a spin a couple of times, then worked on images in Lightroom/Photoshop (that part was extremely important for her, because she works with colors and skin tones quite a bit), she told me that she loved everything about it. So without hesitation, we decided to buy the E-M5 with a couple of lenses (more on lenses further down in the review). I am happy to say that I have no regrets whatsoever for our decision and the E-M5 continues to amaze us to date.

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Specifications

- Sensor: 16 MP Live-MOS sensor & TruePic VI Image Processor

- EVF Resolution: 1.4 million dot

- AF: Contrast-detect AF system with 35 focus points

- IBIS: All new “5 axis” in-body Image Stabilization

- LCD: 3″ 610,000 dot tilt/touch OLED screen

- Construction: Magnesium-alloy and aluminum construction body with advanced splash and dust protection

- Built-in Art Filters: Yes

- Self-cleaning ultrasonic sensor dust reduction system: Yes

- Shutter Durability: 100,000 cycles

- Storage: SDHC/SDXC memory card compatibility for ultra-fast data transfer speeds

- Wireless flash control and a built-in ISO standard hot shoe: Yes

- Built-in digital leveler function: Yes

- Video: Up to 1080/60i full HD video recording capability

- Battery Life: Up to 360 images

- Face Detection Capability: Yes

- Continuous Shooting Speed: Up to 9 FPS at full 16 MP resolution

Detailed technical specifications for the Olympus OM-D E-M5 are available at Olympus.com

16 MP Live-MOS sensor

One of the most important attributes in a digital camera is its sensor – the heart of the camera that is responsible for capturing images. For the first time in Olympus mirrorless cameras, the Olympus OM-D E-M5 features a sensor made by Sony. As you may already know, Sony is one of the largest sensor manufacturers in the world. Sony makes sensors not only for its own branded cameras, but also for a number of other manufacturers – including Nikon, Fuji, Pentax and others. The excellent sensor inside the Nikon D800, for example, is also made by Sony. Because of Sony’s vast experience in sensor manufacturing, they made some of the best sensors in the world. So I applaud the decision by Olympus to use Sony sensors. If Olympus continues to use Sony sensors in the future, it will surely keep up with the competition in terms of image quality, colors and noise – rather important factors when comparing sensors. To date, sensor technology was one of the weaknesses of Micro Four Thirds cameras. See my Nikon 1 V1 review from last year, where it did really well against the Olympus E-PL3, which has a bigger sensor. In comparison, the E-M5 performs on par with the competition, as can be seen from the next several pages of this review.

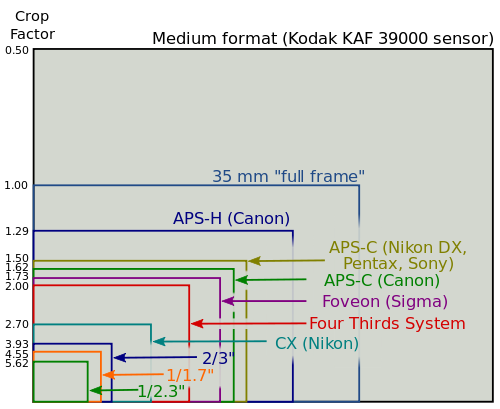

For those of our readers that do not know much about Micro Four Thirds, the term “Four Thirds” comes from the physical size of the sensor that measures 4/3″ and from the 4:3 image aspect ratio. This means that the physical size of the sensor is smaller than APS-C sensors used in DSLRs and mirrorless cameras (about 40% smaller), and the image is not as wide, since APS-C and full-frame sensors use a 3:2 image aspect ratio. If APS-C sensors have a 1.5x crop factor relative to a full-frame sensor, Micro Four Thirds sensors have a 2.0x crop factor (more on this under “Lenses”). So a 12mm lens would be equivalent to a 24mm lens in terms of angle of view (12mm x 2x crop factor = 24mm). You can read more about Micro Four Thirds on Wikipedia. Here is a chart that summarizes sensor size differences (courtesy of Wikipedia):

It is important to know that when it comes to sensors, the physical size of the sensor dictates a few important factors. The first one is image quality and ISO performance. A sensor with a larger physical area would typically yield better noise performance and dynamic range than a smaller sensor (assuming both are of the same generation and image processing pipeline). This puts larger sensors at an advantage when compared to smaller sensors, because they have better overall image quality. The only thing that small sensor cameras can do to compete with large sensor cameras, is to improve the image processing pipeline, attempting to reduce noise via software algorithms. Nikon, for example, knows how to do this quite well on its Nikon 1 cameras, providing excellent image quality in RAW images, despite the smaller sensor size (as shown in my Nikon 1 reviews). Sometimes you will hear people say “Cooked RAW”, which is often described as something negative, almost like cheating. I personally see nothing wrong with tweaking the RAW output to make it look better. In fact, I believe every manufacturer does this to a degree – some more aggressive than others. Otherwise, image quality on most cameras would be the same, especially when their sensors are made by the same manufacturer. Nikon often edges out Sony in noise performance, despite the fact that Sony manufactures sensors for many Nikon cameras. If it wasn’t for Nikon’s ability to tweak the output of the sensor, there would be no image quality differences between the two. Similarly, Olympus engineers were able to achieve great results with the E-M5. As you will see on the next pages of this review, the camera produces excellent image quality that matches some of the best APS-C sensors on the market, except maybe at extreme ISO levels. That’s pretty remarkable, for a sensor that’s 40% smaller than APS-C.

The second factor is resolution. A larger sensor has more physical space, which means that more pixels could be crammed into the sensor. While a smaller sensor could have the same number of pixels as a full-frame camera, its pixels would be significantly smaller, which means more noise would show up in the images. Again, the smaller Micro Four Thirds sensor is at a disadvantage here when compared to larger APS-C sensors. Because the physical size of the sensor is smaller, there should be either less resolution, or smaller pixels. Since the E-M5 has a 16 MP sensor, which has about the same resolution as the Sony NEX-5R that has a larger APS-C sensor, the pixel size is also smaller. The Sony NEX-5R has a pixel size of 4.8µ, while the Olympus OM-D E-M5 is at 3.7µ. However, despite the smaller pixel size, the Olympus offers very impressive performance in comparison, as I stated above.

The third factor is depth of field – smaller sensors translate to larger depth of field. In very simple terms, a smaller sensor would bring more “in focus”, which can be both good and bad. Good for landscape and architectural photography, where maximum depth of field is often needed. But bad for portraiture, where shallow depth of field is often desired for subject isolation. If you have been wondering why your cheap small sensor point and shoot camera or your mobile phone can never really properly isolate subjects from the background, resulting in flat images with everything in focus, now you know why – it is primarily because of the small sensor. Hence, the smaller Micro Four Thirds sensor on the E-M5 can be considered a disadvantage when compared to APS-C sensors when looking purely from the perspective of depth of field. However, as I demonstrate further down in this review, not being able to achieve shallow depth of field and beautifully isolate subjects on Micro Four Thirds sensors is a myth. It is certainly doable – I have used a couple of excellent fast aperture lenses on the E-M5 and I was able to create beautiful portraits with smooth backgrounds. Now I am not here to state that you can achieve the same results on a Micro Four Thirds camera as on a full-frame camera – there are practical limitations to things like lens design. At the end of the day though, how much subject isolation capability one truly needs? For many of us out there (including myself), the E-M5 would be more than sufficient in most situations, even with the above depth of field differences.

The fourth factor is diffraction. When the lens aperture is shrunk or “stopped down” too much, the light rays start bending and interfering with each other, causing image quality to drop. The smaller the aperture, the worse it gets. And unfortunately, the smaller the sensor, the more visible diffraction gets at larger apertures. For example, on full-frame cameras, diffraction can start to appear above f/11-f/16. On APS-C and Micro Four Thirds cameras, it is visible above f/11. And on smaller systems like Nikon 1, it is even smaller, at f/8 and above. While diffraction differences between APS-C and Micro Four Thirds are not huge, they are still there. I performed a number of tests on different Micro Four Thirds lenses using Imatest and the decline in image quality was more rapid on the E-M5 than on the NEX cameras.

Judging from the above list, it looks like a smaller sensor pretty much always loses to a larger sensor on the grand scale of things. However, there is one serious advantage to a small sensor that I have not talked about yet – lens size. The smaller the sensor, the smaller the lens. With small sensors, it makes no sense to design large and bulky lenses, simply because only a portion of the optical surface can be used. Again, if you look at most point and shoot cameras with tiny sensors, you will also often see tiny lenses, not chunky SLR-like lenses. And that’s the biggest advantage of Micro 4/3 cameras in my opinion. Many of the Micro 4/3 lenses are incredibly small and compact, when compared to APS-C mirrorless lenses and especially DSLR lenses.

So when I was in the process of evaluating a mirrorless system for my needs, I paid a lot of attention to all of the above factors. Noise performance and dynamic range were impressive on the E-M5 when compared to NEX systems. 16 MP of resolution was more than plenty for my needs (considering my old Nikon D700 has a 12 MP sensor). I knew that if I needed more resolution, I would be using my Nikon D800 instead. Depth of field was an issue at first, but after using a couple of fast primes and seeing the results, I told myself that I rarely would need more than that. Diffraction is not a big deal either, as long as I can remember to stay below f/11. Lens size was a huge plus for the Olympus – I absolutely loved using the Olympus 12mm f/1.8, 45mm f/1.8 and the Panasonic 25mm f/1.4 lenses. They felt tiny, light and provided excellent image quality (again, more on this below under Lenses).

Therefore, sensor size is not always the most important factor in a camera. Sometimes it is best to look at everything as a whole and then make a judgement. Overall though, I congratulate Olympus on choosing a very balanced sensor for the E-M5.