Focus Speed and Accuracy

The 40mm f/2 autofocuses quickly and almost silently. This is as much due to the camera as the lens, but it’s still great to see the trend continue on the Z 40mm f/2. The accuracy is fantastic and even better than a Nikon DSLR in live view (which itself is very accurate).

Because of the f/2 maximum aperture, the Z 40mm f/2 focuses in very dark conditions without any issue. Compared to an f/4 lens, the 40mm f/2 can autofocus in conditions with just one-fourth as much ambient light. And compared to an f/5.6 lens, it can focus in just one-eighth the ambient light. It’s not quite at the level of an f/1.8 lens, but it’s only 1/3-stop worse.

Lastly, the close-focusing capabilities of the Nikon Z 40mm f/2 leave something to be desired. The lens has approximately a 0.3-meter / 1-foot close focus distance, with a maximum magnification of just over 1:6. This means you can fill the frame with a subject that’s about 21 cm / 8 inches across.

That’s fine for most subjects, but it’s worse than most lenses in Nikon’s lineup. It means that the Z 40mm f/2 would be a bad choice for something like flower photography, let alone even smaller subjects like bugs. Still, at least Nikon’s lineup also has the lightweight (although more expensive) 50mm f/2.8 MC macro lens as an alternative if you need more magnification around this focal length.

Distortion

The Nikon Z 40mm f/2 has a very low amount of distortion, just 0.62% barrel distortion. It’s a welcome result, although not exactly a huge surprise. Midrange prime lenses frequently keep their distortion under 1%.

On top of that, many photographers will never see this distortion in the first place, even if they’re shooting lots of straight lines like architecture. The reason is that Adobe Lightroom has a built-in lens profile for the 40mm f/2 that completely removes distortion, and it cannot be disabled with this lens.

I wish that Adobe would allow the profile to be disabled, but at least with the 40mm f/2, there wouldn’t be much difference one way or another. Any shift in composition between the corrected and uncorrected images is quite minimal.

Sharpness

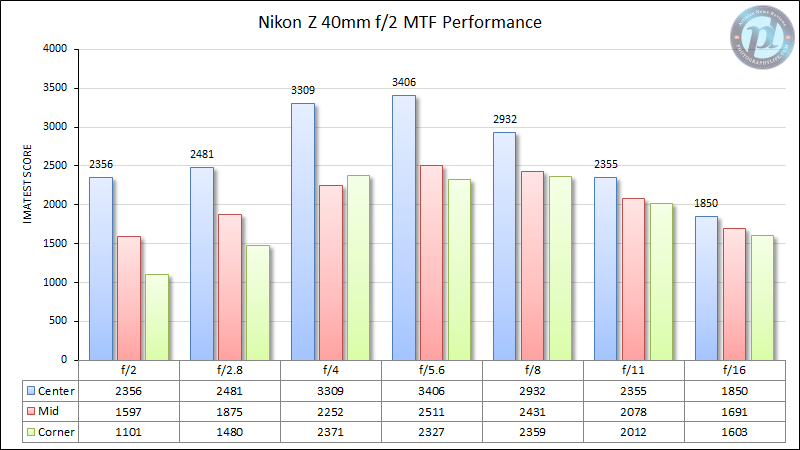

The Nikon Z 40mm f/2 is fairly sharp, but it’s definitely not Nikon’s highest-resolving mirrorless lens yet. Here’s how it performs in our Imatest results:

The lens starts out a bit weak at both f/2 and f/2.8, but it gets substantially sharper at f/4 and f/5.6. The corners are strong at the “landscape apertures” of f/5.6 through f/11. The lens gradually loses performance at narrower apertures like f/11 and f/16 due to diffraction, but this is true of all lenses and not a fault of the Z 40mm f/2.

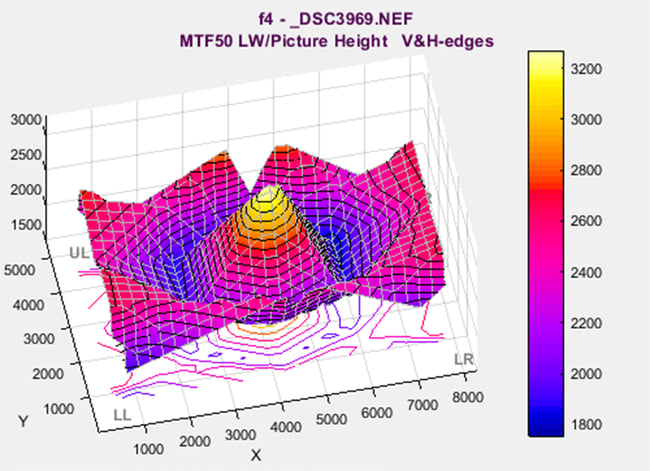

The Nikon Z 40mm f/2 has pronounced field curvature, meaning that the “plane” of sharpest focus is curved rather than flat. Field curvature is responsible for the odd-seeming result at f/4 in the Imatest graph above, where midframe sharpness appears worse than corner sharpness. In reality, this loss of midframe sharpness is due to out-of-focus blur instead of blur from other lens aberrations.

To help visualize things, here’s our measurement of the lens’s mustache-type field curvature at f/4:

Field curvature is present at other apertures, too, but it affects the Imatest graph most noticeably at f/4 in our tests. In practice, you may not care too much about field curvature as a photographer; test charts exaggerate the issue relative to most three-dimensional subjects.

That said, it still depends on your subject. If you’re shooting a landscape at an overlook where everything is approximately at infinity focus, field curvature can cause a significant loss in sharpness in parts of your photo. On the other hand, if you’re photographing something like close-up scenes with a shallow depth of field, the issue may not be relevant at all.

As for focus shift, the Z 40mm f/2 has quite a bit. If you focus at f/2, then stop down to something like f/2.8 or f/4, your focus point will migrate behind your subject. With the Nikon Z 40mm f/2, it’s important to stop down to your desired aperture first, then focus, if you want to eliminate the problem.

Note that Nikon Z cameras are programmed to focus at your selected aperture, so long as you’re using f/5.6 or wider. This effectively prevents the issue of focus shift, so long as you always stop down your lens before focusing.

Coma

Another image quality issue with some lenses is coma, a lens aberration that can make dots of light in the corner of a photo look like smears. Coma isn’t usually visible in everyday photography, but for something like Milky Way photography, it can be a factor. Lenses longer than about 24mm aren’t usually popular for Milky Way photography, but given the maximum aperture of f/2, the Z 40mm f/2 isn’t a bad choice for photographing the stars. So, I wanted to put its coma performance to the test.

The image shown below is an extreme crop from the top-left corner. Specifically, I cropped the Nikon Z7’s 45-megapixel sensor down to a minuscule 949 × 631 pixels and didn’t do any resizing; it’s a direct excerpt from the original image:

This is a solid, though not stunning, result in terms of coma. There are certainly lenses with less coma than the 40mm f/2, but considering how much I cropped the photo above, some level of coma is to be expected. I’d still be happy to shoot this lens at f/2 for Milky Way photography – although I’d rather shoot it at f/2.8 or f/4 and use image stacking to reduce the noise.

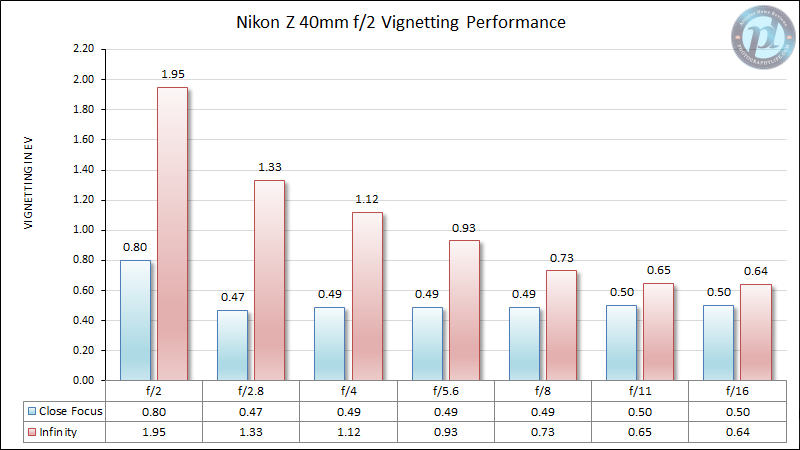

Vignetting

In uncorrected images, the 40mm f/2 has fairly high levels of vignetting wide open, though it depends on your focusing distance. It’s the worst at infinity focus, where it approaches two stops of vignetting in the furthest corners at f/2. At other apertures and focusing distances, the vignetting is much better.

Here’s a full chart of vignetting levels:

This isn’t terrible performance, but it’s nothing special. By comparison, the Nikon Z 50mm f/1.8 S maxes out at 1.65 stops, and the Z 35mm f/1.8 S at 1.83 stops. (Both of those measurements are at f/1.8, too, theoretically putting them at a disadvantage in this comparison.) Anything under about 1.5 stops doesn’t need to be corrected in most images, and anything under 1.0 stops is negligible in my book.

Keep in mind that Adobe Lightroom’s lens profiles for the 40mm f/2 directly read information from your in-camera vignetting reduction setting. If you want your photos from this lens to have full corrections in Lightroom by default, you need to turn the vignetting correction to “High” in-camera. This is true even if you’re shooting .NEF files. I recommend turning the in-camera corrections to “Medium” or “High” to minimize your post-production work.

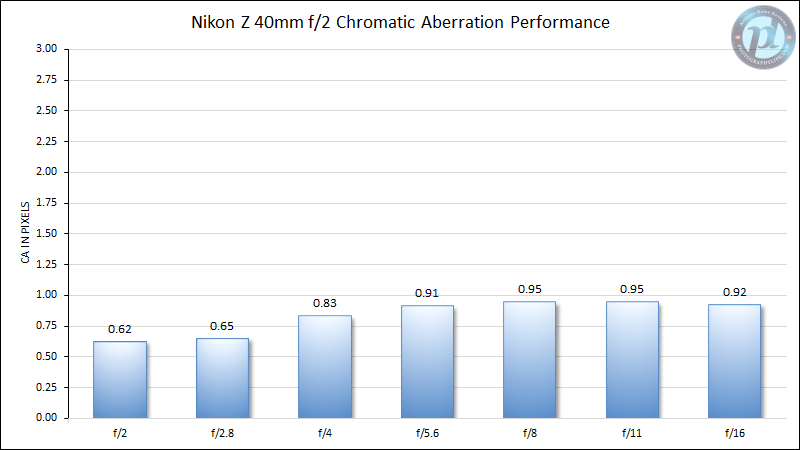

Lateral Chromatic Aberration

There is a low amount of lateral chromatic aberration on the 40mm f/2 at every aperture. Here’s the chart:

Anything under about one pixel is almost impossible to notice in real-world images, even with chromatic aberration corrections turned off. The Nikon Z 40mm f/2 meets that standard. Even though a handful of top-tier lenses perform better than this, I wouldn’t worry about lateral chromatic aberration at all on this lens.

Bokeh

Many photographers pick wide-aperture prime lenses because they want to capture photos with a shallow depth of field and pleasant bokeh. At 40mm and f/2, this isn’t quite a bokeh machine like an 85mm f/1.4 would be, but you can still get plenty of background blur.

How does that blur look, though? I had high hopes for the bokeh on the 40mm f/2, but I came away somewhat disappointed.

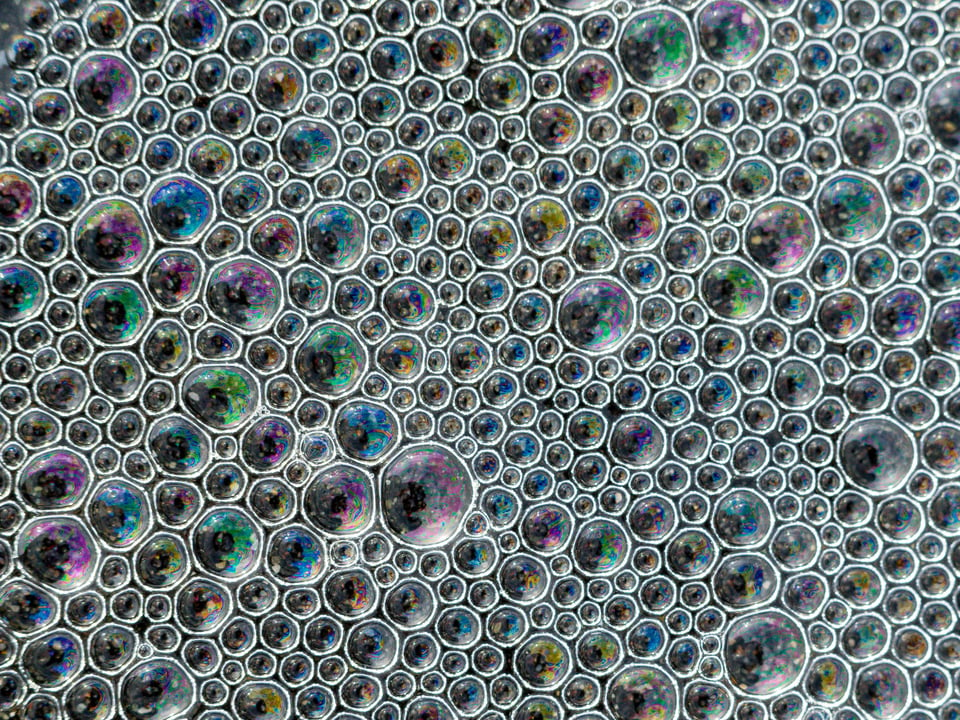

The good news is that it’s possible to get get pleasant bokeh with almost any lens, including the Z 40mm f/2, if your background is sufficiently out of focus. Since f/2 is a wide aperture, you can certainly take photos with the Z 40mm f/2 that have soft out-of-focus backgrounds. Just get a bit closer to your subject, like this:

However, if the out-of-focus background is only “moderately” out of focus, you’ll notice some issues with the Z 40mm f/2’s bokeh. For example, here’s the same scene as above, but focused a bit farther in the distance:

This time, the out-of-focus background looks pretty hectic. Here’s a crop from the top left to demonstrate some of the issues more clearly:

The shape here is oblong and distracting. The out-of-focus highlights have sharply-defined edges and high levels of longitudinal chromatic aberration (AKA green and purple color fringing). It’s an interesting look, but not one that I think most photographers are after.

Here’s another example that shows something similar at a further focusing distance:

It’s the same sort of look – some sharply-defined background blur with an unusual shape.

Again, I should mention that the busy bokeh is the most noticeable with the 40mm f/2 when your background is mildly to moderately out of focus. If you shoot at f/2 and focus close to the lens’s minimum focusing distance, the background blur on the Z 40mm f/2 is very pleasant, mainly because everything is completely blown out. It also remains pleasant at narrower apertures like f/2.8 and f/4 so long as the background is sufficiently out of focus.

Still, if you’re searching for the creamy bokeh of high-end portraiture lenses, the Z 40mm f/2 probably isn’t the lens for you. Apart from the useful maximum aperture of f/2, I don’t notice many things worth praising about the Z 40mm f/2’s background blur.

Sunstars and Flare

One of the most demanding tests of a lens is to point it at the sun. Good lenses maintain a high level of contrast and create well-defined blades of light around the sun (AKA sunstars). Lower-quality lenses produce distracting flare and badly-defined sunstars.

I don’t expect a lens like the Nikon Z 40mm f/2 to produce great sunstars, which are more the domain of wide and ultra-wide lenses. In that regard, the lens meets my expectations – the sunstars are pretty bad!

As for flare, you can already see a bit in the photo above, but it’s not terrible. Pointing the lens at my phone’s flashlight in the dark, here’s the amount of flare at three different apertures:

The red dot flare is pretty high at f/16, although unfortunately the same is true of most mirrorless lenses, so I can’t fault the 40mm f/2 too much. There is also some rainbow-colored flare right at the point of light at every aperture. Overall, though, it’s a good performance.

Things get a bit worse when the bright point of light is closer to the midframe of the image:

Overall, I’d trust some lenses more than this one in backlit situations, but the Z 40mm f/2 performs well here. That’s probably thanks to the small number of lens elements – just six in total – which minimizes the potential for internal reflections. However, Nikon did forego its best anti-flare coatings on the 40mm f/2 to reduce its price, and at some level, it shows.

The next page of this review dives into the Z 40mm f/2’s sharpness numbers a bit more, including comparisons against other lenses that you may be considering. So, click the menu below to go to “Lens Comparisons”:

Table of Contents