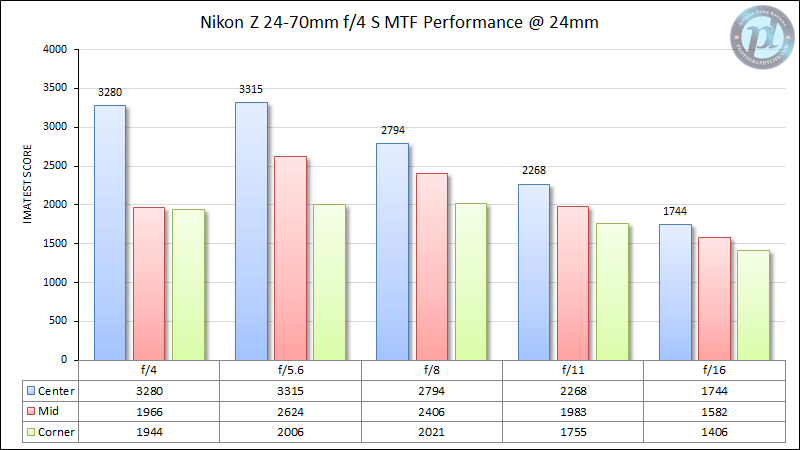

The Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S is far from the only midrange zoom available for the Z series! There are several competing options that you may be deciding between. Below, I’ll show you my sharpness measurements from a variety of lenses from 24mm to 70mm to help you make up your mind.

24mm (and 28mm)

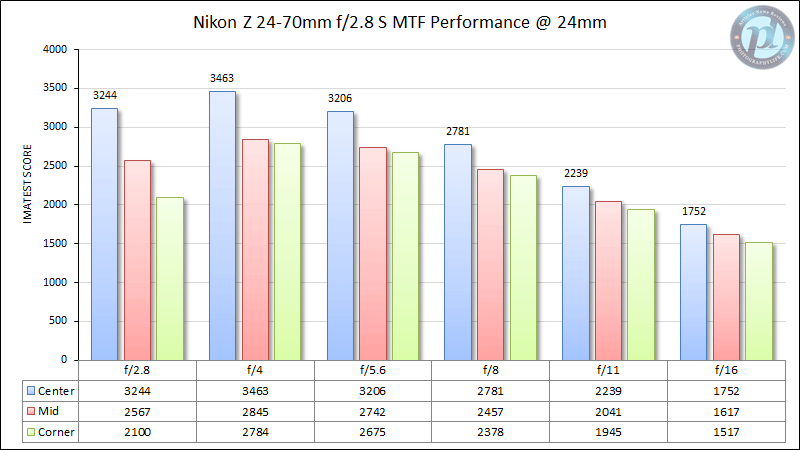

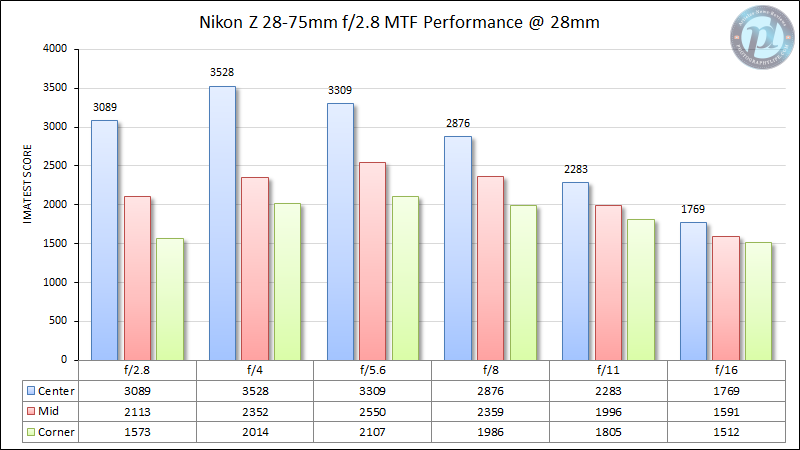

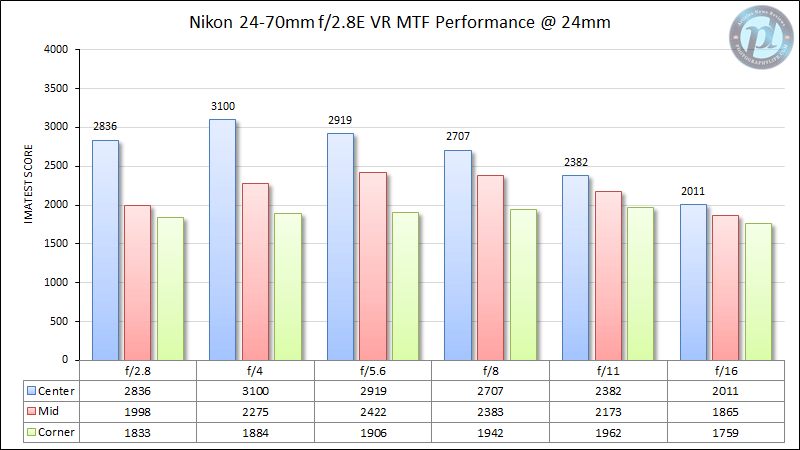

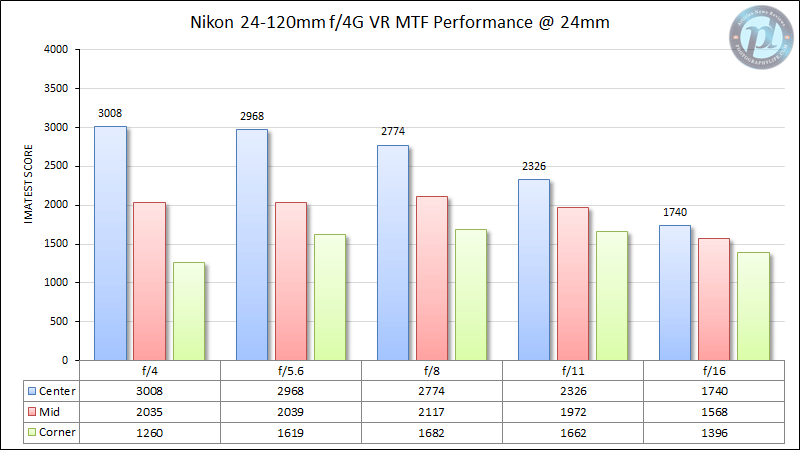

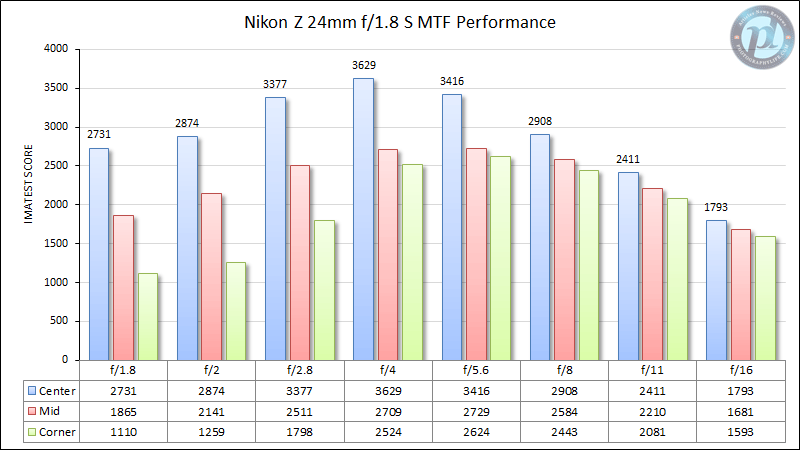

As you can see, the 24-70mm f/4 S is roughly in the middle of the pack. This isn’t bad considering that it’s one of the least expensive of these lenses, and this is some really touch competition. Here’s how I would rank the sharpness of these nine lenses at 24mm (and 28mm in one case):

- Nikon Z 24mm f/1.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S

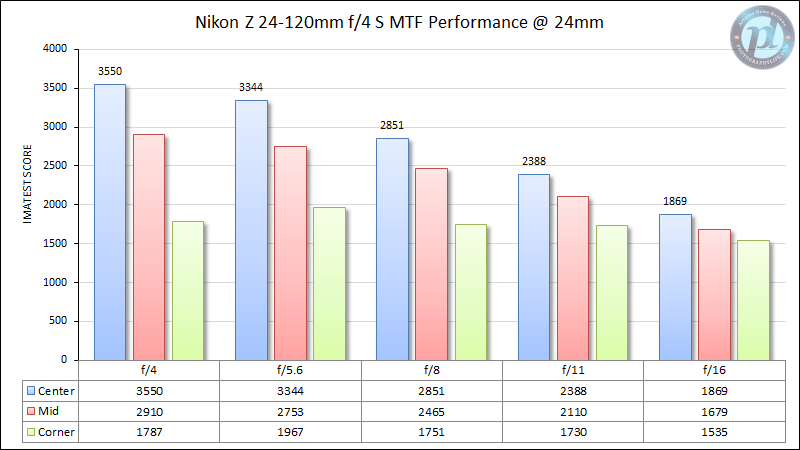

- Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S

- Nikon Z 28-75mm f/2.8

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S

- Nikon AF-S 24-70mm f/2.8E VR

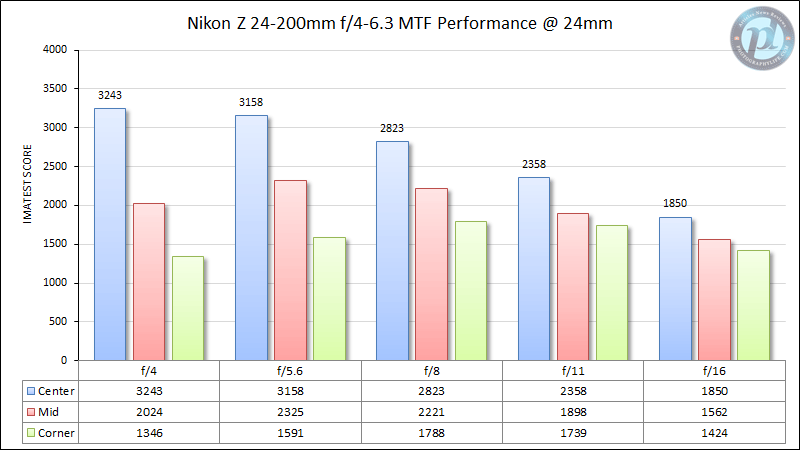

- Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR

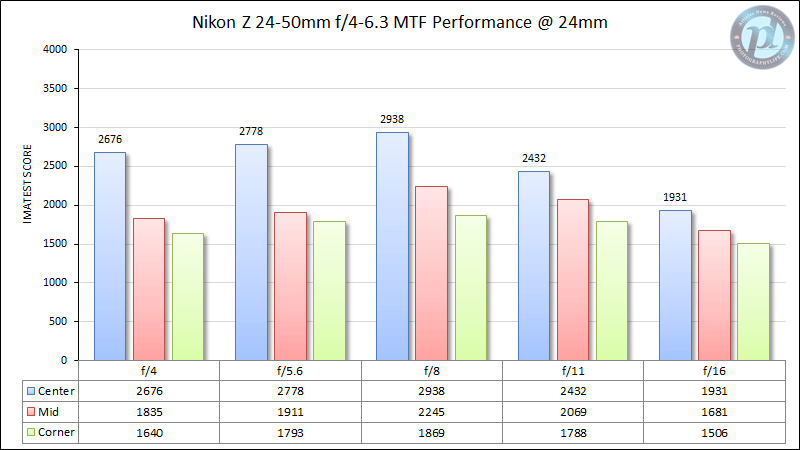

- Nikon Z 24-50mm f/4-6.3

- Nikon AF-S 24-120mm f/4G VR

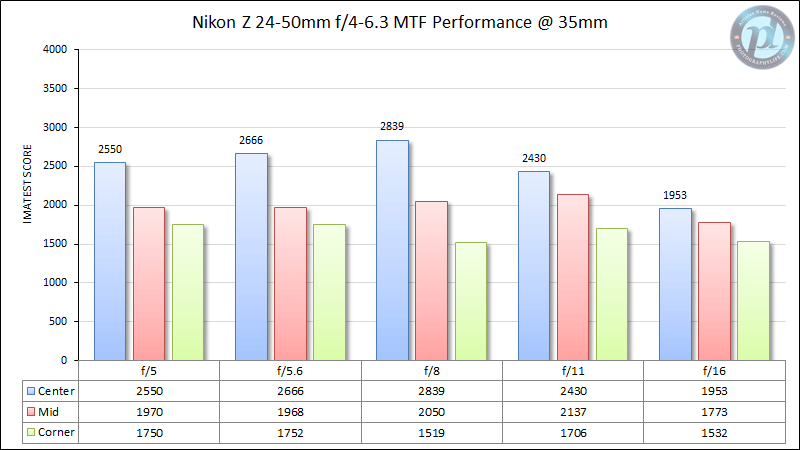

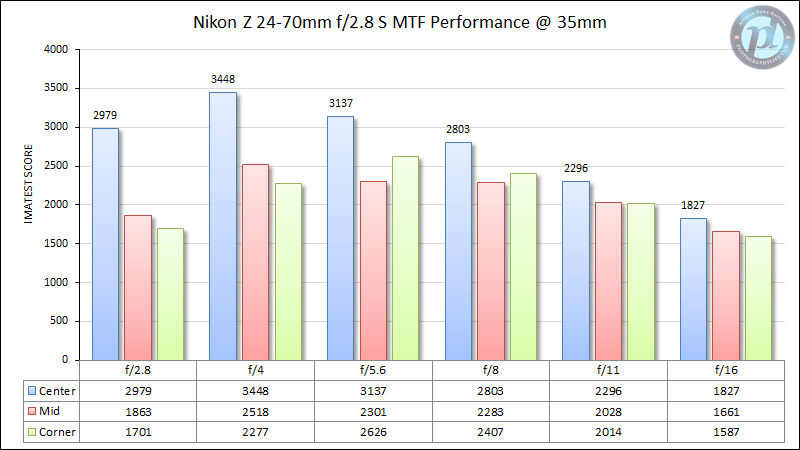

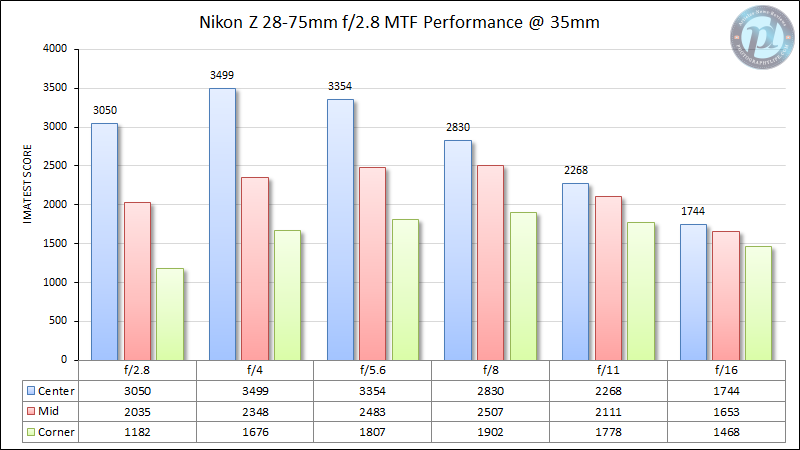

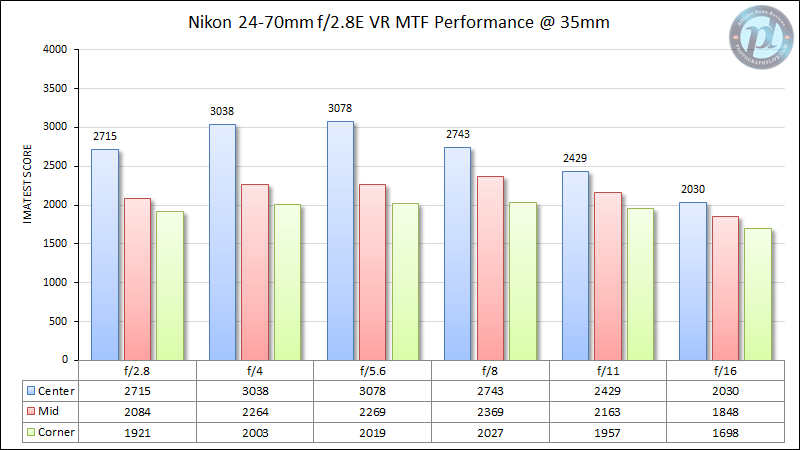

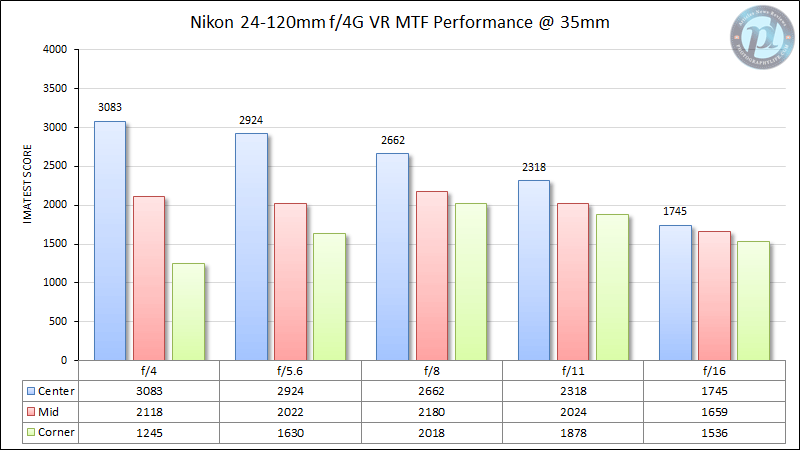

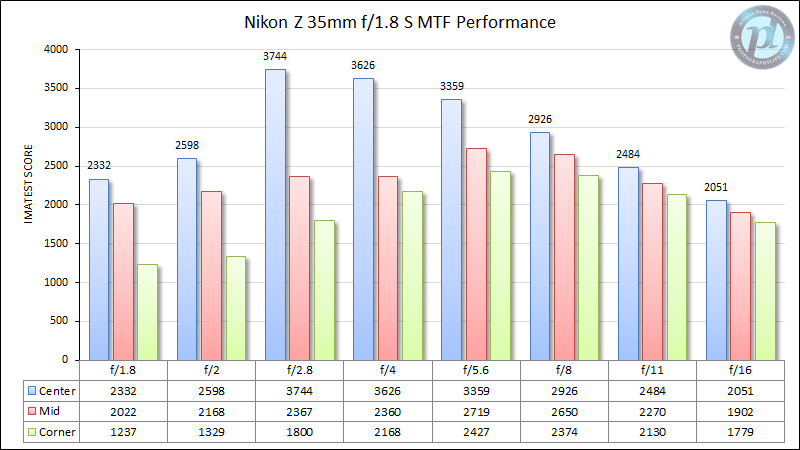

35mm

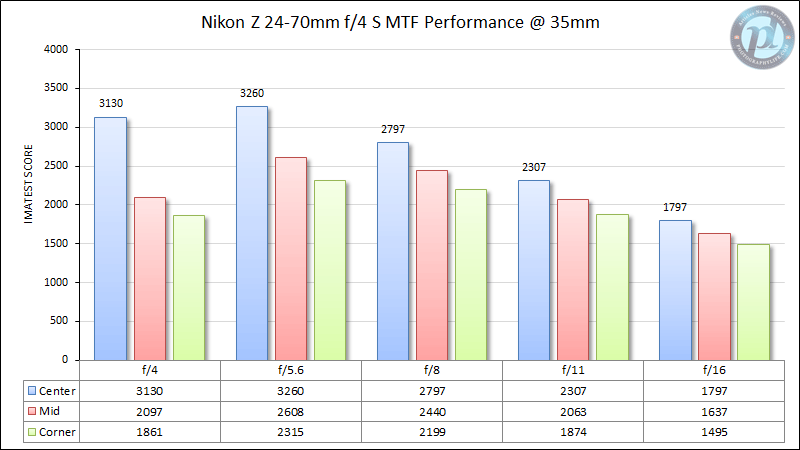

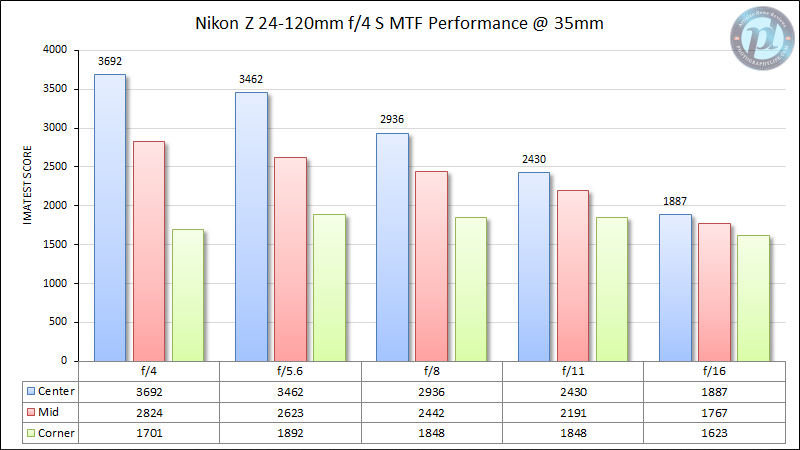

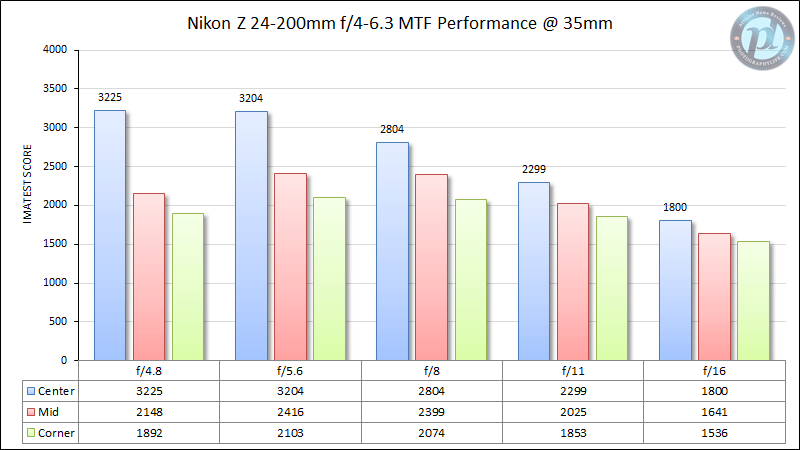

It’s a pretty similar story here. The Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S is in the middle of a very impressive pack. At 35mm, I would rank the nine lenses as follows:

- Nikon Z 35mm f/1.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S

- Nikon AF-S 24-70mm f/2.8E VR

- Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR

- Nikon Z 28-75mm f/2.8

- Nikon Z 24-50mm f/4-6.3

- Nikon AF-S 24-120mm f/4G VR

However, there’s definitely some subjectivity in these rankings. For example, although the Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S is sharper in the center and midframes, the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S is sharper in the corners – so, some photographers may rank it 3rd instead of 4th for their personal situation.

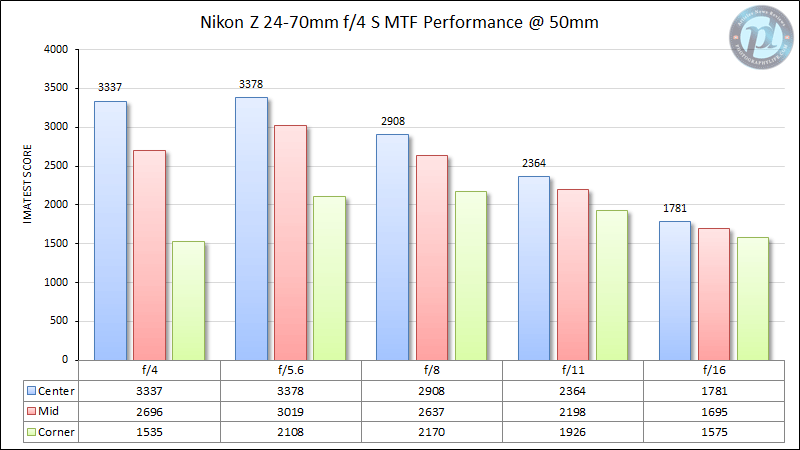

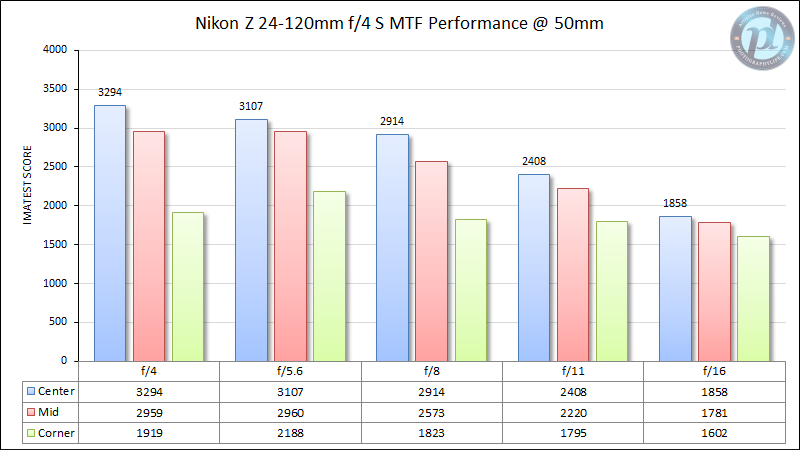

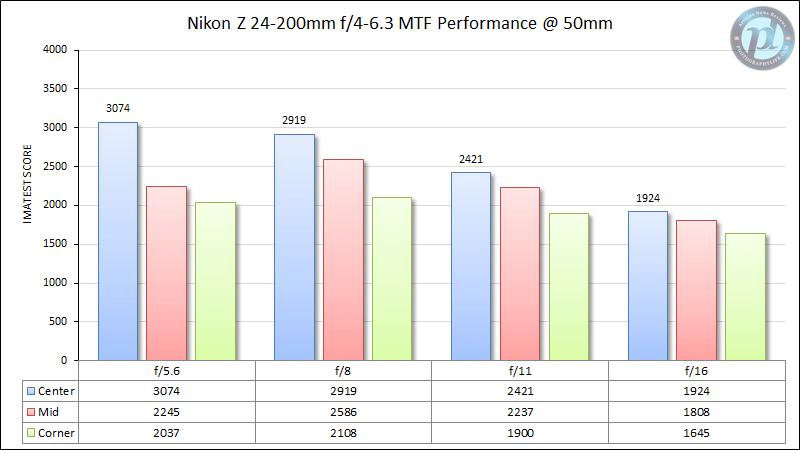

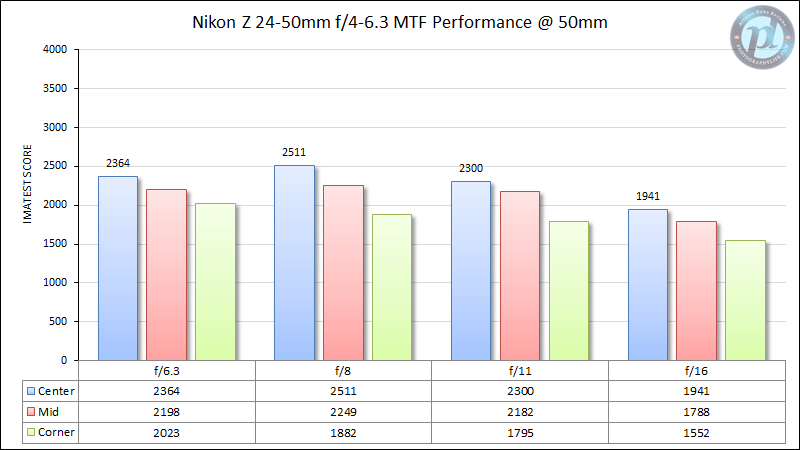

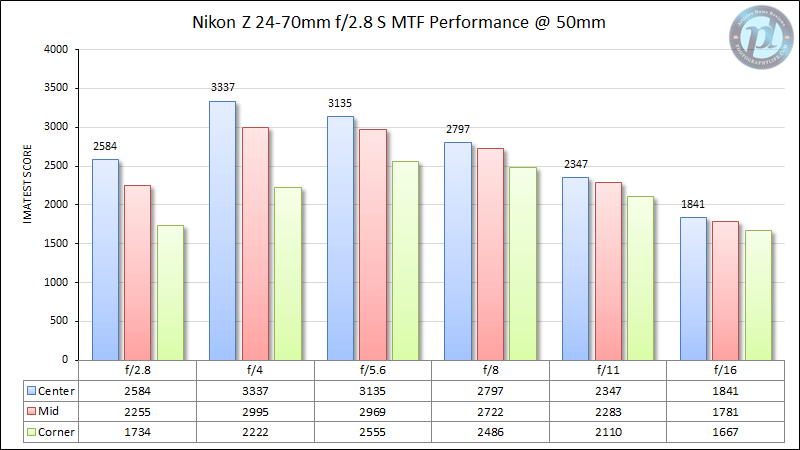

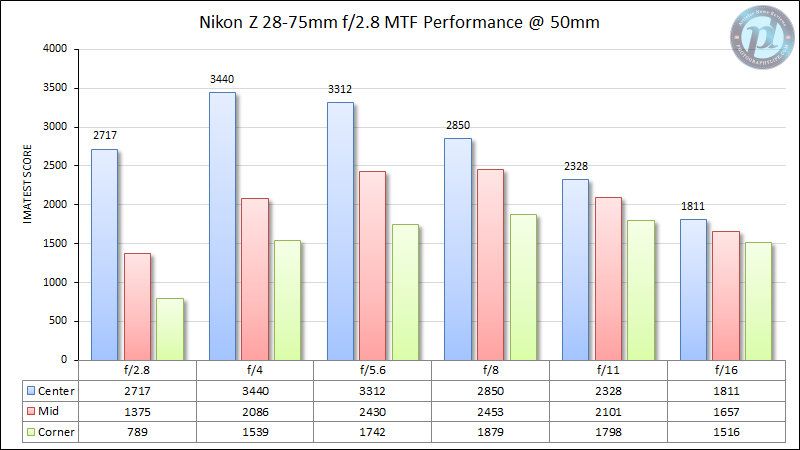

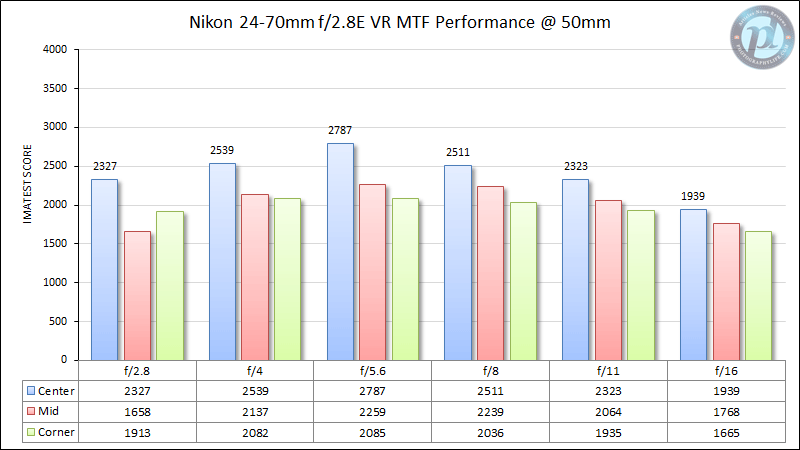

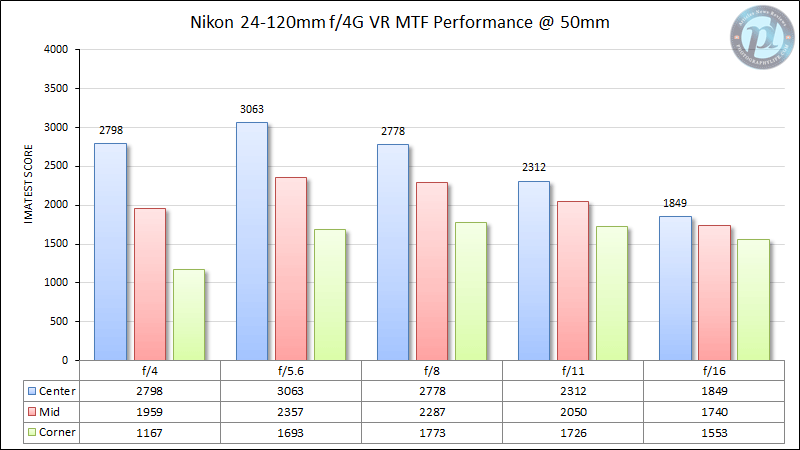

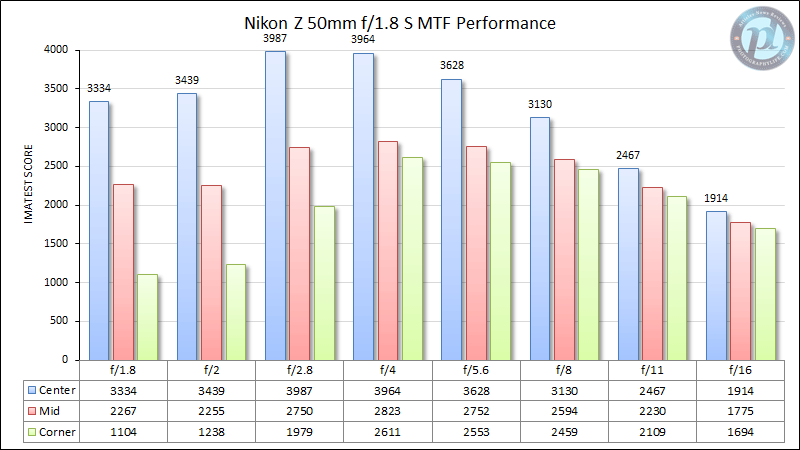

50mm

While the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S gets a bit weaker at 50mm, so do most of these lenses. Here’s how I would rank them this time:

- Nikon Z 50mm f/1.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S

- Nikon AF-S 24-70mm f/2.8E VR

- Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR

- Nikon Z 24-50mm f/4-6.3

- Nikon Z 28-75mm f/2.8

- Nikon AF-S 24-120mm f/4G VR

As before, there’s some subjectivity in ranking them like this. I encourage you to look at the more detailed numbers if you want to get a better picture of things!

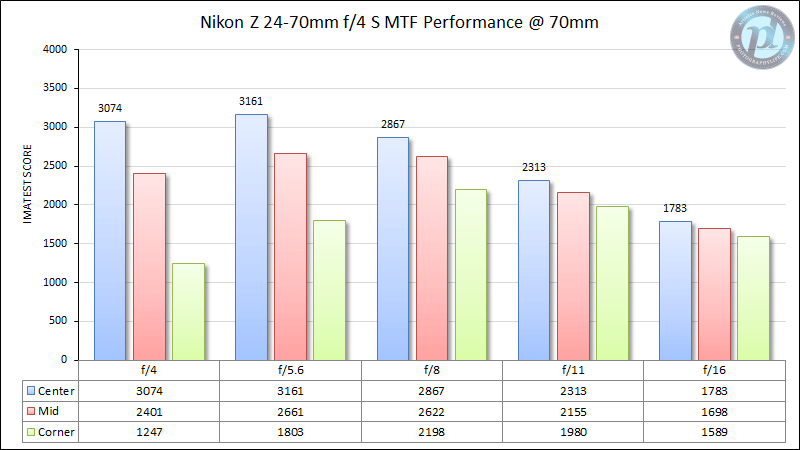

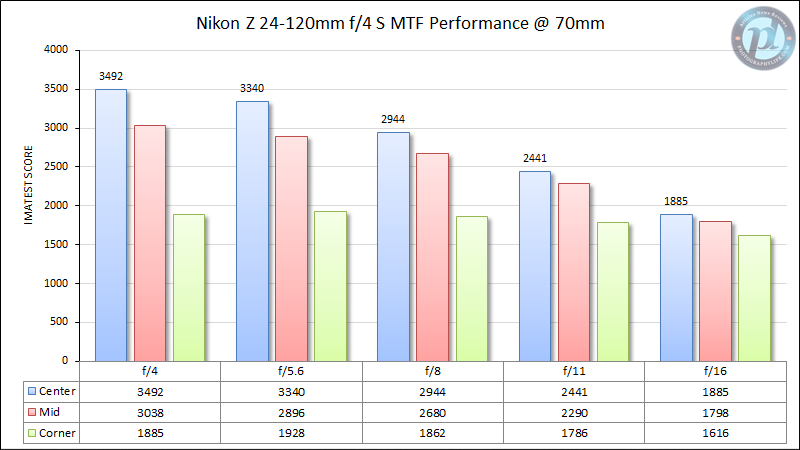

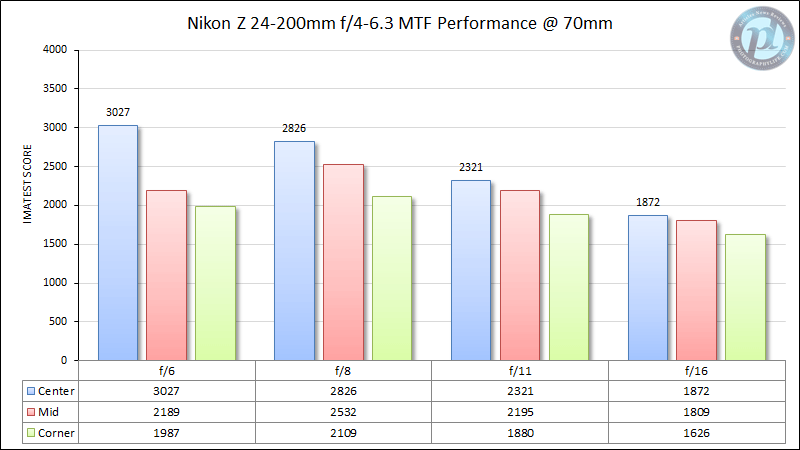

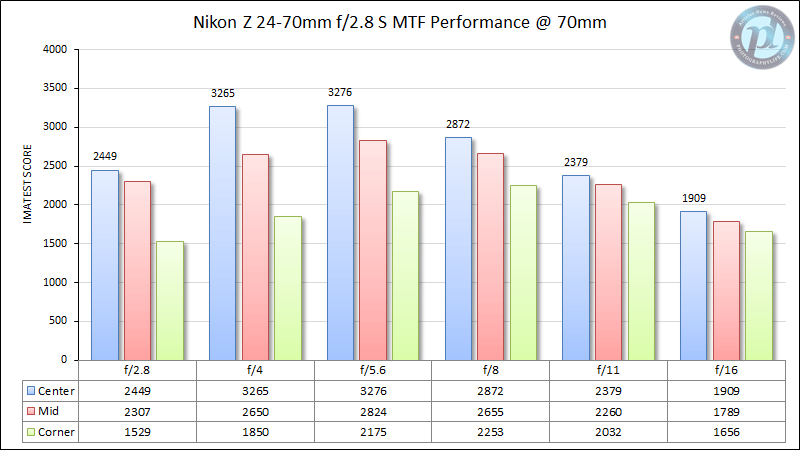

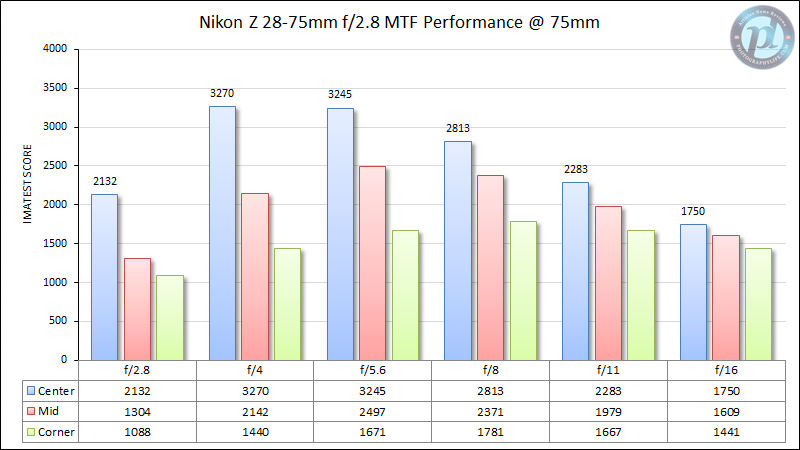

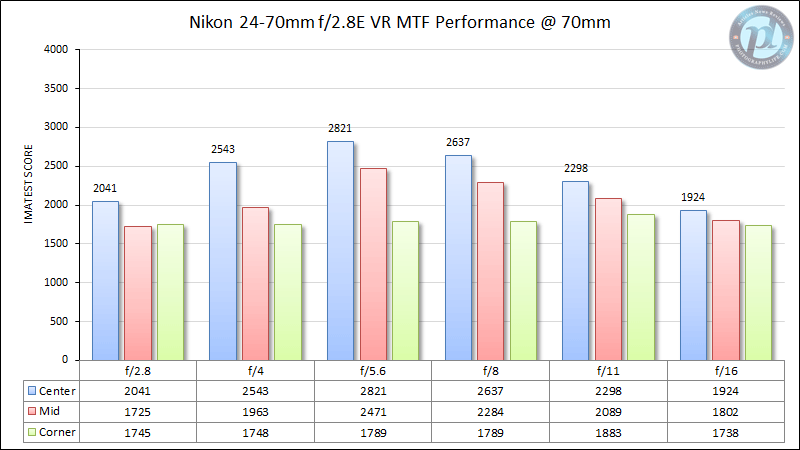

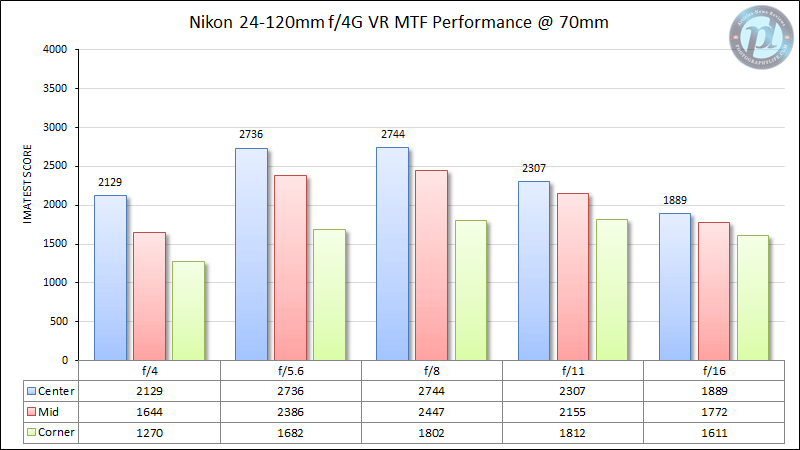

70mm (and 75mm)

There aren’t as many lenses to show at this focal length, since the Nikon Z 24-50mm f/4-6.3 doesn’t reach 70mm, and there aren’t any 70mm Nikon Z primes yet to include for reference. Out of the seven remaining lenses, here’s how I would rank them:

- Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S

- Nikon Z 28-75mm f/2.8

- Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR

- Nikon AF-S 24-70mm f/2.8E VR

- Nikon AF-S 24-120mm f/4G VR

These rankings are really close, though. There isn’t as much of a difference between how the lenses perform at 70mm.

Conclusion

The Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S may not be the #1 sharpest lens at any focal length, but it’s never near the bottom of the pack, either. It does a solid job throughout the range of focal lengths and apertures. In order to clearly beat it, you would either need to get the expensive Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S, or you would need to get a prime lens.

The Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S is also a slightly stronger performer overall, but the difference isn’t huge. It actually favors the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S if the corners at wider focal lengths are your priority (which would apply to a lot of landscape photographers, for example).

If you want a more detailed head-to-head comparison, you may want to check out the following articles, which dive deeper into these numbers but also cover more than just sharpness:

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S versus Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S versus Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S versus Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S

- Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S versus Nikon Z 28-75mm f/2.8

I hope this gives you a good sense of how the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S stacks up to the various alternatives that are available. It’s definitely a sharp and high-performing lens, especially for the price, even though I wouldn’t rate it as best-in-class.

You can also check out our lens reviews page if you want to compare it against any other lenses, including lenses from companies like Canon and Sony.

The next page of this review sums up everything and explains the pros and cons of the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S. So, click the menu below to go to “Verdict”:

Table of Contents