Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 Focusing Performance

In good light, autofocus on the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 is just as fast as on the other Z lenses. However, the narrow f/4-6.3 maximum aperture means that the 24-200mm runs into low-light focusing issues sooner than lenses with a wider maximum aperture. Especially compared to an f/1.8 prime, the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 engages Nikon’s slower “Low Light AF” mode much earlier. Along the same lines, in very dim conditions, the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 gives up autofocus before other Nikon Z lenses. Keep in mind that this isn’t due to a bad focusing mechanism within the 24-200mm, but simply because its narrower maximum aperture isn’t capable of gathering as much light to help the autofocus system in dark environments.

As for autofocus accuracy, the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 retains the phenomenal performance of Nikon’s other Z lenses for focusing on static subjects in AF-S mode. I’ve mentioned this a few times, but the Nikon Z system is the first camera setup that allows us to autofocus on our test charts in the lab rather than manually focusing using rails, which we’ve always done before. The Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 is no exception and has excellent autofocus accuracy with any Z camera.

In terms of manual focus, it’s a bit more of a mixed bag. Like most of Nikon’s Z lenses, the focusing ring on the 24-200mm isn’t mechanically coupled to the lens elements; it’s a focus-by-wire system instead. As a result, manual focus on the 24-200mm doesn’t always inspire confidence. The biggest issue is that the manual focus system doesn’t just depend on how far you turn the focus ring, but also how fast you turn it. That can make it trickier to pinpoint the right focusing distance.

I’m sure that most of the Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3’s potential users are going to rely on autofocus far more than manual focus, at which point there’s hardly anything to complain about. It’s only when you need manual focus that you may be wishing for one of Nikon’s older AF-S lenses rather than this one.

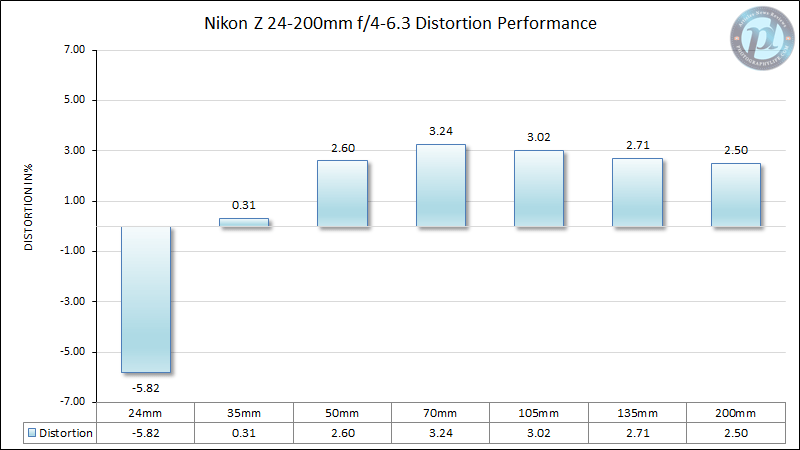

Distortion

The Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR has extensive barrel distortion at 24mm, which becomes nonexistent around 35mm and turns into moderate pincushion distortion at 50mm and beyond:

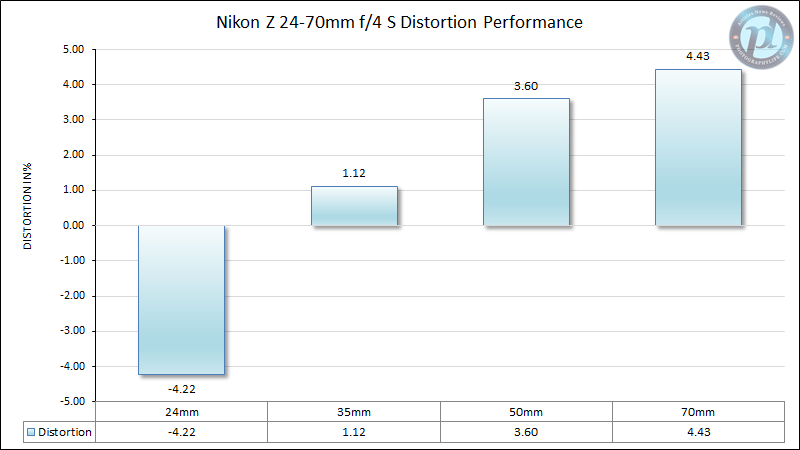

For comparison, here’s a similar graph for the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4:

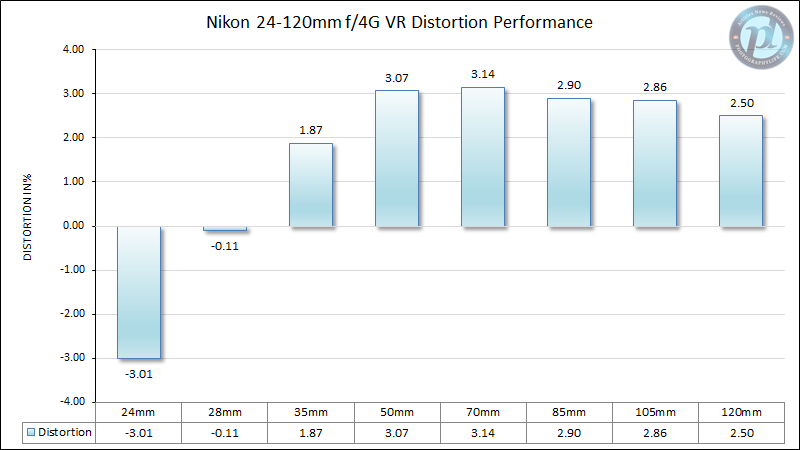

And for the Nikon F 24-120mm f/4:

Keep in mind that the y-axis is different on the three graphs above. Comparing the actual numbers, we can see that the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 has more barrel distortion at 24mm than either the Z-mount 24-70mm f/4 or the F-mount 24-120mm f/4. At the longer focal lengths, it has about the same amount of pincushion distortion as the F-mount 24-120mm f/4, and actually a bit less pincushion distortion than the Z 24-70mm f/4. In short, the Nikon Z 24-200mm does have significant distortion, but it’s not outside the norm of other Nikon zooms.

I should also mention that many photographers who buy the Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 will never see this distortion in the first place, even if they’re architectural or real estate photographers who capture a lot of straight lines. The reason is that Adobe Lightroom has a built-in lens profile for the Nikon Z 24-200mm that almost completely removes distortion, and the lens profile cannot be disabled. (The same is true if you use Nikon’s own editing software or shoot JPEGs.) The only way to see to the original, distorted images is to open your RAW files in some other software like Capture One that allows you to disable profile corrections.

To me, the inability to see the uncorrected images in Lightroom is a problem. How often have you taken a photo where the composition is just slightly off, and a handful of pixels on either side could make a difference? With this lens, you may indeed have captured those pixels in the field, but you’d never know it if you’re using Lightroom or Nikon’s editing software.

I don’t mind that these profile corrections are enabled by default, and I get why Nikon’s own software won’t let you remove them. But seriously, Adobe, allow us to disable them if we choose.

Sharpness

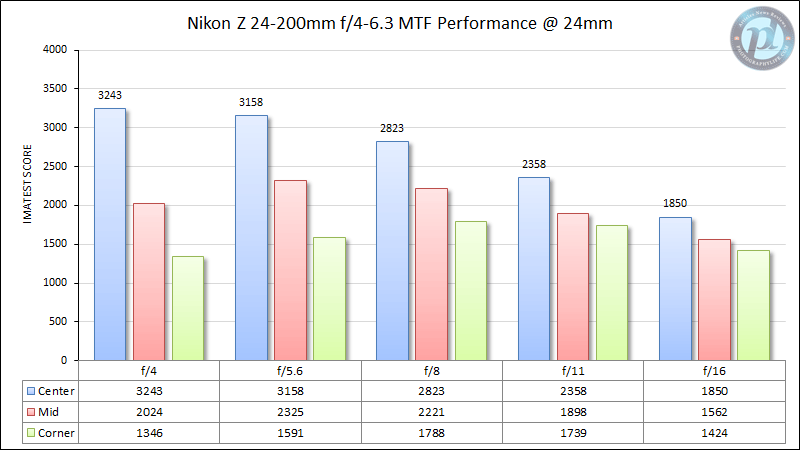

The Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 is very sharp for a superzoom, though not at the level of some of Nikon’s other Z lenses. That will become clearer on the next page of this review – Lens Comparisons – but for now, let’s take a look at the lens’s performance throughout its range of focal lengths. Here’s 24mm:

This is pretty good performance in the center at 24mm throughout the aperture range, and it’s ok in the corners. As always, sharpness drops off a lot at f/16 due to the unavoidable effects of diffraction, so it’s more important to consider the performance from about f/4 to f/8. Taking all areas of the frame into account, the sharpest aperture overall is either f/5.6 or f/8, where the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 puts up a respectable, though not outstanding, performance.

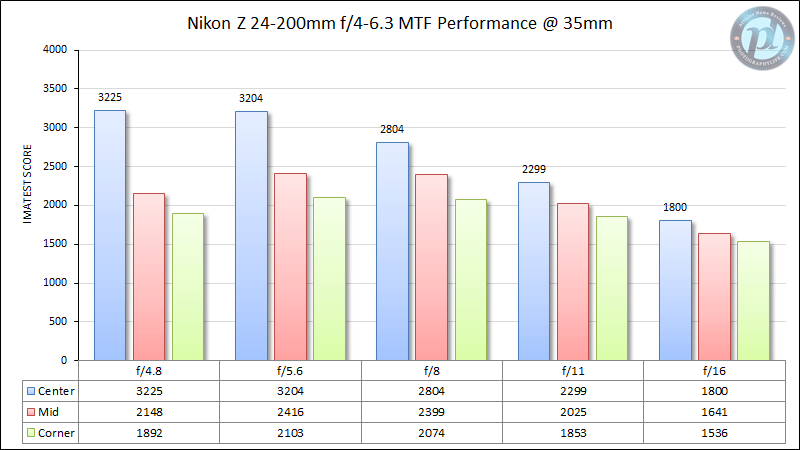

Here’s 35mm:

This is the sharpest focal length of the Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3, and it’s a surprisingly impressive performance. The corners are sharp throughout the aperture range (again, other than at f/16), and the lens reaches its maximum sharpness at f/5.6. While lenses like the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 and Nikon Z 35mm f/1.8 still beat it overall at 35mm, the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 is more than sharp enough at this focal length.

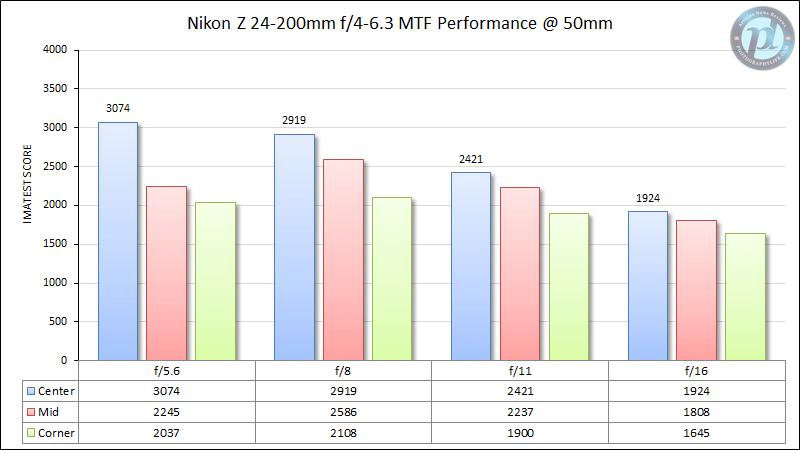

Here’s 50mm:

Central performance decreases slightly at 50mm compared to how it was at 35mm, but corner performance remains high. The midframe actually sees its best performance numbers at 50mm.

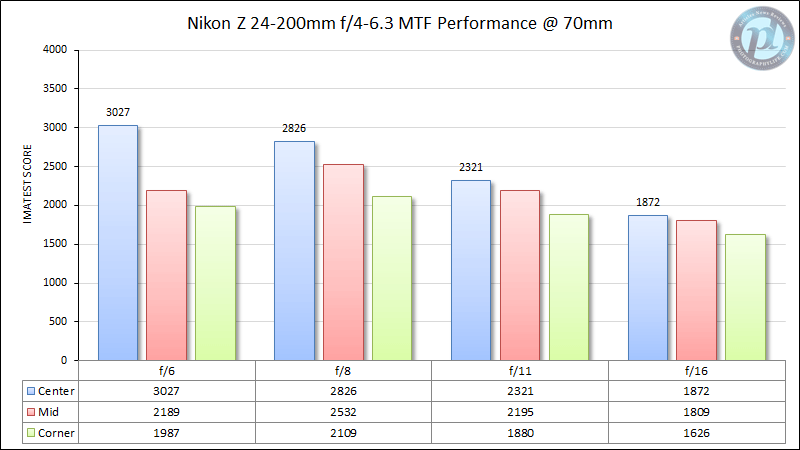

Here’s 70mm:

This looks very similar to the performance at 50mm, with a strong midframe and corner, and only slightly weaker central performance than at 35mm. Not bad at all.

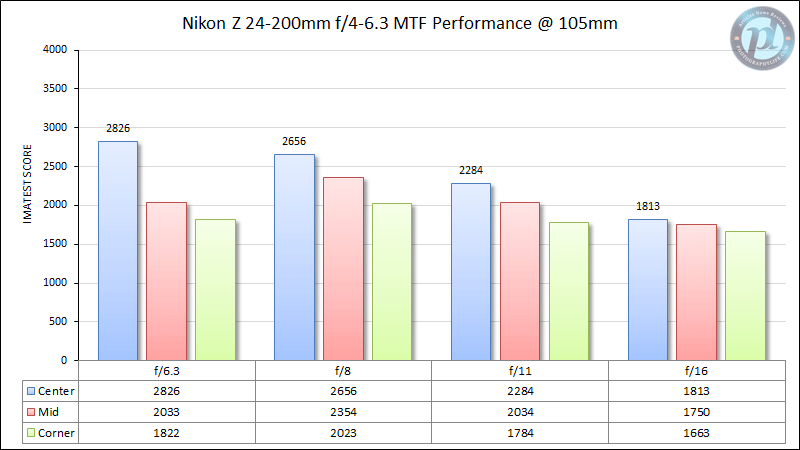

Here’s 105mm:

We’re now starting to see a general decrease in sharpness compared to the prior focal lengths. The 24-200mm is hardly bad at 105mm, but it’s about back to where it was at 24mm.

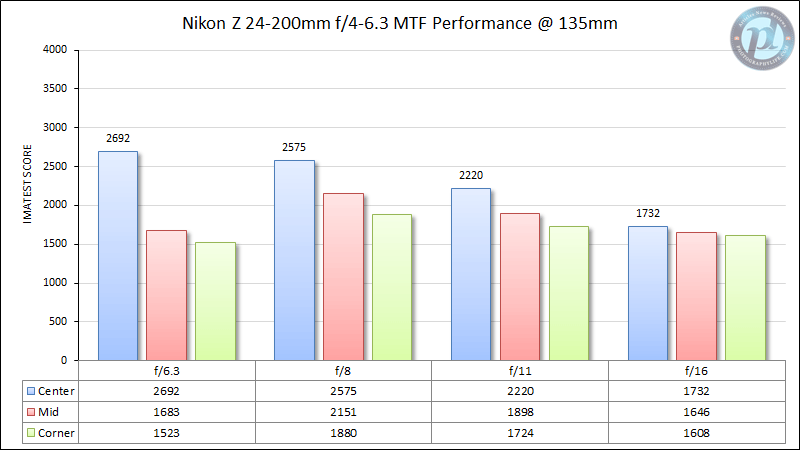

Here’s 135mm:

Performance at 135mm continues the trend of decreasing sharpness as the lens is zoomed in farther and farther. Central sharpness is the worst we’ve seen so far, and while the corners aren’t terrible, it would be nice if they were a bit crisper.

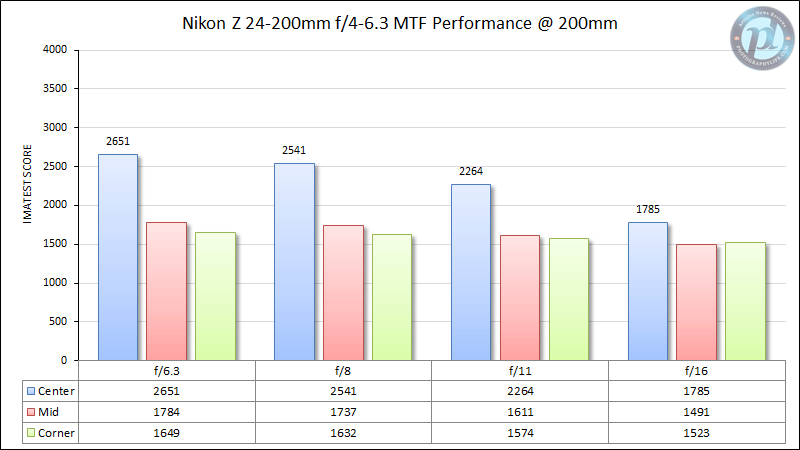

Finally, here’s 200mm:

As you can see, this is the weakest focal length on the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 in the center, midframe, and corners. You can see that the 24-200mm’s midframe and corners basically maintain “f/16-level sharpness” regardless of what aperture you use. Of course, f/16-level sharpness is still acceptable for large prints assuming you’ve used good technique. But the wider focal lengths are definitely better.

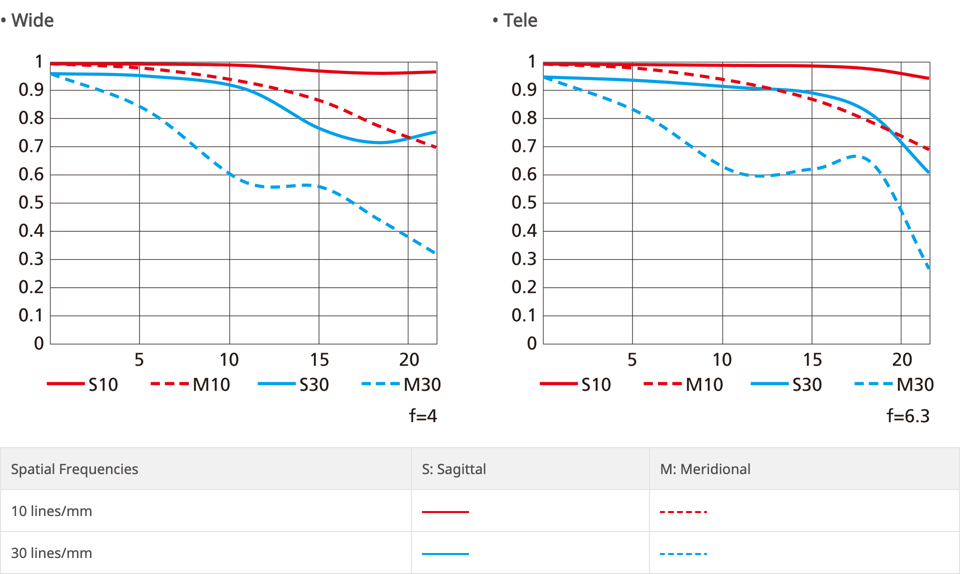

For comparison, here is the Nikon-provided MTF chart:

Overall, I give the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 surprisingly high marks for its sharpness performance. From about 35mm to 70mm, there’s nothing to complain about. At 24mm and 105mm, the lens is a bit softer but still good. It’s only in the 135-200mm range where I’d want more sharpness – and even then, it’s hardly awful. The corners stay acceptable throughout the zoom range, and we didn’t detect any focus shift at all with this lens (where the point of focus changes as you stop down the aperture).

Compared to other zoom lenses around this price point, like the Z 24-70mm f/4 and F-mount 24-120mm f/4, the 24-200mm holds its own, as you’ll see on the next page of the review. Considering that it’s a lightweight superzoom, it definitely exceeded my expectations.

However, these results come with a caveat: We tested three copies of the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 for our review, and this one was the sharpest. The other two weren’t unusable, but they clearly showed worse performance on our test chart (and in real-world images side-by-side).

Some sample variation is always going to happen with lenses. It’s not something you should worry about too much. Still, most of the other Nikon Z lenses we’ve tested so far have had minimal sample variation from copy to copy, including the 24-70mm f/4. Only the 14-30mm f/4 and this 24-200mm f/4-6.3 have had meaningful sample variation in our tests. So, if you do get the 24-200mm, you’ll want to make sure that you didn’t get a decentered copy.

But how can you tell? Here’s the process I recommend:

- Find some subject that’s at infinity, such as a town in the distance when viewed from the top of a hill.

- Put it at the center of your photo and focus on it with the center point. Use the lens’s widest aperture.

- Without refocusing, recompose your shot and take four successive photos where the same subject is in each separate corner of the image. Make sure you’re using a stable tripod, there’s no wind, and you’ve enabled the self-timer.

- If the subject looks about equal in sharpness at all four corners, it’s very likely a good copy. If one or more corners are clearly and consistently less sharp than the others when you repeat this test, it’s very likely decentered. When the decentering is extreme, you should return your copy of the lens.

I realize that returning lenses is easier in some markets than others, and it can be especially tough if you’re buying used. You know better than me if it’s an issue for you or not, but if possible, I’d lean toward buying from someone who accepts returns.

The good news is that most copies of the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 are going to be totally fine, and decentered copies will be obvious if you perform the test above. But it does seem to be a slightly bigger issue with this lens than some others, unless we just had particularly bad luck, so be aware of it when you’re making your purchasing decision.

Vignetting

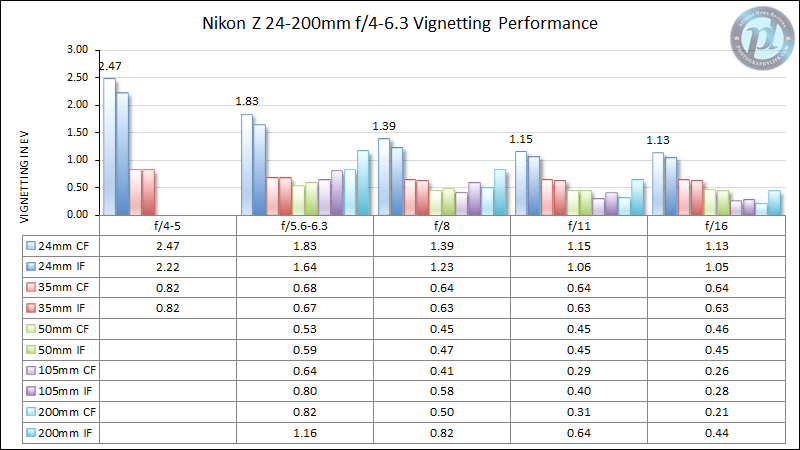

The Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 has surprisingly minimal vignetting considering the extreme zoom range. It’s worst at 24mm and f/4, but even then, it’s hardly objectionable for a superzoom, and stopping down to f/5.6 reduces it quite a bit. At 50mm and beyond, the vignetting is minimal enough even wide open that you’ll rarely find yourself needing to correct for it (the built-in distortion correction in Lightroom does crop out the most extreme corners and make the vignetting look a bit better, but even in the uncorrected images, it’s not bad).

Here is how Imatest measured vignetting levels on this lens from 24 to 200mm:

Here’s an example of how minimal it is at 200mm wide open, with no vignetting correction applied:

Chromatic Aberration

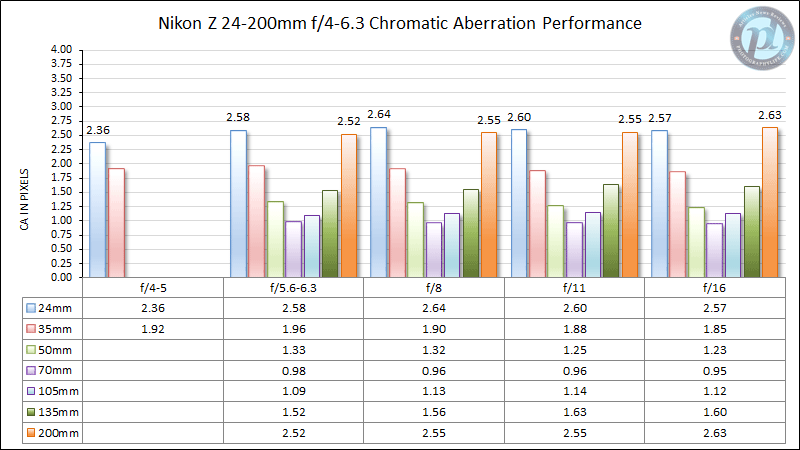

The Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 has low to moderate levels of chromatic aberration depending on your focal length. Here’s our full chart:

As you can see, the worst chromatic aberration is at 24mm and 200mm. In between, it gradually improves, with the best results coming at 70mm. Changing the aperture hardly changes the level of chromatic aberration at all. Although this is high for a Nikon Z lens (at least at 24mm and 200mm), it can still easily be corrected in post-processing without leaving obvious artifacts behind.

By comparison, the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 S has some of the lowest levels of chromatic aberration we’ve seen on a zoom at just 1.22 pixels of CA at the most. The Nikon Z 14-30mm f/4 is also low with a maximum of 1.72 pixels of CA. But plenty of Nikon’s F-mount lenses are worse than this. For example, the Nikon F 24-120mm f/4 maxes out at 2.85 pixels of CA, and the Nikon F 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5 maxes out at 2.94. So, compared to the broader market of zoom lenses rather than just Nikon Z gear, the 24-200mm f/4-6.3 is pretty much within expectations.

Sunstars and Flare

The Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR is surprisingly solid in terms of flare performance, especially considering how many lens elements it has. It retains a lot of contrast even in backlit situations, with minimal veiling flare (though increasing as you zoom in). However, it still lags behind lenses like the Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 and especially Nikon’s Z prime lenses for overall flare performance. While testing this lens, I would periodically get unexpected specks of flare even if the sun was slightly out of the frame.

Part of that has to do with the lens hood. Lens hoods on most zooms can only be optimized for the widest focal length – in this case, 24mm. As you zoom beyond 24mm on the 24-200mm f/4-6.3, the lens hood offers less and less protection from flare. As such, you’ll want to keep an eye out once you get to about 35mm or 50mm that the sun outside your frame isn’t adding a colorful speck somewhere in the photo.

As for sunstars, I’ve seen better. Here’s the weak sunstar at 27mm and f/8 (plus a demonstration of some slight green flare/lower contrast below the sun):

The rounded 7-blade diaphragm on the 24-200mm doesn’t produce great sunstars, although you can get some passable ones if you shoot close to 24mm at a narrow aperture like f/16. The smaller and brighter your source of light, the sharper the sunstars will be.

In short, the Nikon Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 isn’t the best Nikon Z lens for shooting directly into the sun, but your results won’t be dreadful if you do. At a minimum, it has better flare performance than I expected on a superzoom and isn’t far behind Nikon’s other Z-series zooms.

Next up, let’s compare how the 24-200mm’s sharpness looks versus some of Nikon’s other current lenses. Click the menu below to go to the next page of this review, Lens Comparisons:

Table of Contents