Nikon D850 Focus Stacking Overview

This section has been written by John “Verm” Sherman.

Before I got hooked on the hernia-inducing joy of hand-holding super-telephoto glass, I went through a brief infatuation with macro photography. It was fun exploring a world that I couldn’t see with my bare eyes, but technically bug photography was a pain in the butt. Never enough depth of field and if you wanted to focus stack it was very time-consuming and tedious to refocus either with the lens or a macro-rail. So I was excited when Nikon incorporated a focus stacking feature (which Nikon wrongfully called “focus shift” in the camera menu – see what Focus Shift actually stands for in photography!) in the Nikon D850. With focus stacking, you set the number of exposures you want, the time between shots, and the amount of shift between shots and the D850 does all the refocusing for you and puts the exposures into one separate folder for ease of use later when stacking in third party software.

Sounds great, so how does it work in practice? Let’s check it out.

My first subject was a moth carcass. It died of natural causes. I state this because there is a despicable trend of bug photographers going out and killing their subjects just to take a photo of them. I absolutely detest this practice as well as putting bugs in the freezer to slow them down (something I tried once with tragic consequences for the poor tarantula and regretted so much I gave up on bug photography). Much better to find your subjects early on a cold morning before they get moving or if you want a dead bug find one that reached the end of its life span naturally.

But I digress. The moth looked a tad moth-eaten, but he was glad to stay still atop the light table for as long as it took. I manually focused on the nearest part of the moth and just guessed at some settings. I used the Nikon 105mm f/2.8G VR macro lens set to f/11, and took 50 exposures with the shift set at 2 (from a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being a greater shift). I set the time between shots at 0 seconds and enabled silent mode so as not to wake the dead. I shot RAW plus JPEG fine and used the JPEGs to stack the images shown here (the D850 is new enough that Lightroom doesn’t support its RAW images yet, but should in a few weeks when I can go back and use my RAW files).

I was too lazy to set up a tripod so I just propped the D850 up on a few books, turned VR off and pointed the lens at the moth. As I was shooting in manual with a steady light source I did not enable exposure smoothing. Programming the settings is very quick using the touch screen instead of scrolling with the camera buttons. I hit start and three seconds later the D850 started shooting (this delay allows any camera shake to subside and is a default value you can’t change). Though the shutter itself is completely silent, there is a single small thunk as the mirror flips up (the same sound you hear when you enable live view – if you are already in live view you won’t hear this) then a tiny repetitive noise from the lens focus motor as it chugs along from shot to shot. A few seconds later had my folder of shots. I then took the shots and processed them in both Zerene Stacker and Helicon Focus (more on this software later). Voila. Everything worked great.

Next, I found this live, but sluggish Green Lacewing. After a youth spent as a voracious slayer of aphids and devourer of mites, this fella is enjoying a more mellow nectar-sipping adulthood. Again, the setup was quick and the results good.

For the lacewing I went with a 100 shot stack but as it turned out I only needed the first 33 shots to capture from front to back of the insect and the rest of the shots just continued focusing on the background and showing off all the dust on my light table. If I knew the distance of each step shift it would really help but Nikon gives no suggestions as to starting points. I was simply relying on guesswork.

The D850 will keep shifting focus between shots until it reaches the number of exposures you designate or if the lens reaches infinity before that it will quit there. I would love it if you could focus on the nearest point you want in focus, then focus on the furthest point you want in focus and then the camera would do all its shifting between those points. As it is I would check out the last shot from the sequence on the camera monitor to see where the D850 had focused – if it was beyond the back of my subject then everything would be fine but I would have to cull through my images to get rid of the frames that were unnecessary.

Here’s a different version from the same lacewing sequence, but instead of emphasizing the delicate wing structure, I culled out shots towards the end of the sequence so I could keep the head in focus, so as to bring more attention to the insect’s face and friendly expression. I like both versions.

After bugs, I figured I’d try out some flowers and see how the D850 worked with a third party lens. These chives were shot with the Tamron 150-600mm at close to its minimum focus distance of 7 feet.

There was a slight breeze wafting the blossoms about 1/4-inch side to side, but the stacking programs did a decent job aligning the separate shots into the whole you see here. This is only possible because the stack from front to back on the flowers was a short distance and the background was far enough away to remain a featureless blur. Had there been much detail in the background and I had continued focusing past the flowers then there would be issues with ghosting because of subject movement. there is some haloing around the edges, but this was largely suppressed by taking the darks down in the tone curve.

I had no problems with the D850 communicating with the Tamron 150-600mm. Again, I guessed at the settings and went 10 shots at 10 wide step width and f/10 and got lucky.

Focus stacking is not just for close-up work, it’s also great for landscapes. This can give that tack sharp look from very close all the way to infinity. Like with these pine cones about a foot from the camera all the way back to the volcano in the distance.

I set the camera for 30 shots, but it reached infinity after 17 clicks and stopped by default there. I was shooting at f/8. This was a result I couldn’t get using hyperfocal focusing on the 20mm and stopping all the way down to f/16 as you can see here. The very closest and furthest points are a bit soft, though at web resolution this might be hard to discern.

Taking the Guesswork Out

One way to take out some of the guesswork would be to drearily photograph rulers at different settings with different lenses and compile cheatsheets. Horrid work but somebody has to do it, right?

Single shot

And Stacked

Going through this exercise, at the maximum step width of 10 and at 1:1 on the 105mm macro lens set at f/5.6 the camera racks the focus out 0.9mm per shot. Given the usable depth of field of the 105mm at f/5.6 at this magnification is about 1/4 to 1/3mm, I obviously need to either reduce the step distance or stop the lens to get more depth of field. Or so I thought. But when I stopped down to f/16, instead of stepping 0.9mm between exposures and overlapping my depth of field, the D850 started stepping roughly 3mm between exposures. This indicates that the step depth is tied to aperture, not a fixed distance at a certain magnification.

So stopping down didn’t work (and anyway, a step width of 10 is ridiculous for macro work – I had just chosen that to experiment at the extreme), let’s see what a step width of 5 would do. A 30 shot stack at 1:1 with f/5.6 spanned nearly 8mm or roughly 1/4mm per step. This is enough to overlap my DOF at f/5.6 for a good sharp stack. I repeated the experiment at f/16 and got just under 1mm per shift at 5 wide and 1:1. Here’s the evidence.

The greater range of sharpness in the latter is not from the increased depth of field from stopping down to f/16, it is from the greater step width. You can actually see this quite well while watching the stacking program at work as each shot being rendered flashes up on the monitor and you can track the focus point from shot to shot.

To compile cheat sheets for every lens you own at various apertures and step widths would take so long you wouldn’t have any time left to go out and shoot. My advice at this point is to experiment (and record the settings and results) with the most common situations you might encounter and come up with your optimal settings. For example, my 20mm is great for landscape work so I’d figure out what aperture/step width settings would get a good shot from minimum focus distance (0.66 ft or 0.2m) to infinity. At a step width of 5 and f/2.8 it takes 76 shots, at f/5.6 it takes 36 shots. 76 shots? Why that could take almost 20 seconds. Who has time for that? The good news is that from 1.3 ft to infinity and f/2.8 it only takes 23 shots or just 12 at f/5.6. Step width is not linear and increases as you approach infinity, but so does your depth of field in each frame so you’re covered.

This section of the review might never get finished if I try to figure out which step width works best for which situations. I’ve been experimenting a bunch and have no solid conclusions yet, but I do have some basic advice. Everything I shot at a step width of 5 looked great from 1:1 macro to sweeping landscapes. I’m going to save myself some headaches and just leave it at 5. The D850 will shoot up to 300 frames in sequence, more than enough for most situations barring perhaps microphotography. If you’re lazy you can just set the frames for 300, the step width at 5, compose the shot, rack the focus to the minimum (though in the interest of time I would actually manually focus on the nearest part of the shot I want in focus), then hit start. Unless you’re shooting a macro lens, the lens will reach infinity long before 300 shots and the D850 will automatically shut off then. The only drawback to this method is if the subject stays still for most of the shots then decides to move before the stack is complete. Not much you can do about this.

If you want everything sharp from near to infinity, go ahead and stop down to f/8 or f/11. Chances are your lens is very sharp at these apertures, and you’ll end up having to deal with far fewer files. As well if you shoot wider open you may end up with issues from skinny foreground objects going so blurred that the stacking program overlaps sharp background detail over them like this.

If you want to limit the depth of field for that creamy dreamy background look, open the lens up to keep your background blurred like in this hollyhock shot.

As with the chive shot earlier, a featureless blurred background can help mask out slight subject movement. If you are planning on leaving the background out of focus limit the shot number, but be sure to check your camera monitor to make sure the last shot of your stack reaches far enough back.

Zerene Stacker vs Helicon Focus

The D850 only takes the sequence of photos – it won’t compile the final stacked image. For this, you need to go to third party software. You can focus stack in Photoshop, but most serious stackers seem to prefer either Zerene Stacker or Helicon Focus.

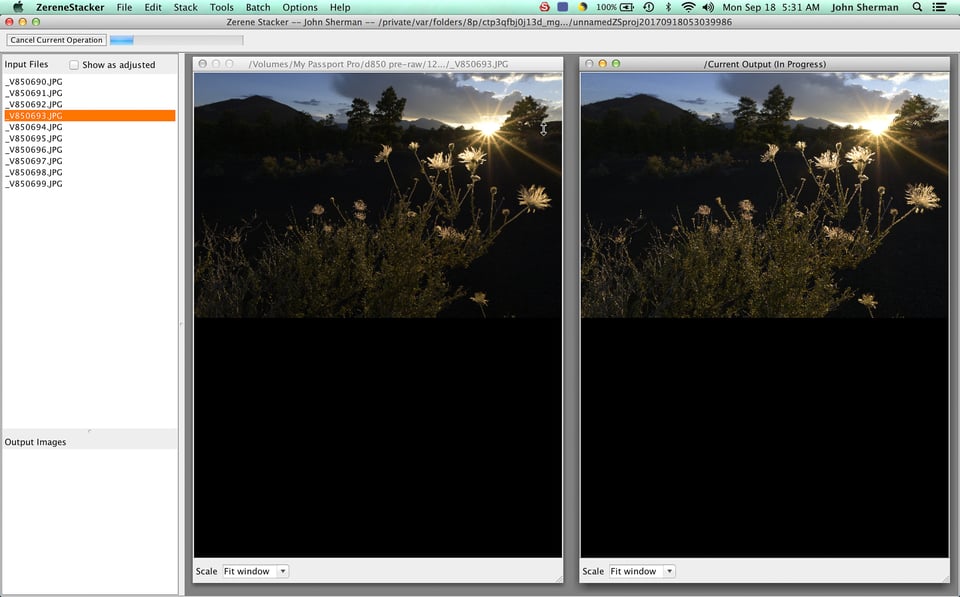

I’ve owned Zerene Stacker for half a decade but because stacking was arduous back in the day (both in-camera and with the computer) I literally hadn’t used it in several years. It took me a few minutes to reacquaint myself with the program. Once I did I got fine results with the moth and lacewing shots. Zerene Stacker works with jpegs and tiffs, but not RAW files. Hence my workflow in the past was to import a huge stack of RAW files into Lightroom, go out for a beer or six while they loaded, then batch process them to my taste and export as jpegs. Next, I would drop the jpegs in Zerene Stacker and let it stack them watch the cool display as the stack came to life. The novelty of this wears off pretty quick though and Zerene Stacker is not a particularly quick program (it took me roughly 12 minutes stack 100 jpegs). Zerene Stacker runs two algorithms, DMAX and PMAX of which PMAX is the better choice for hairy little things like bugs. DMAX is better for smooth objects.

As you can see, the layout is pretty bare-bones and you’ll be running through the menus to find what you need. Not very user-friendly at first but relatively easy to pick up given practice. In the end, it’s the final output that counts and Zerene Stacker produces good results.

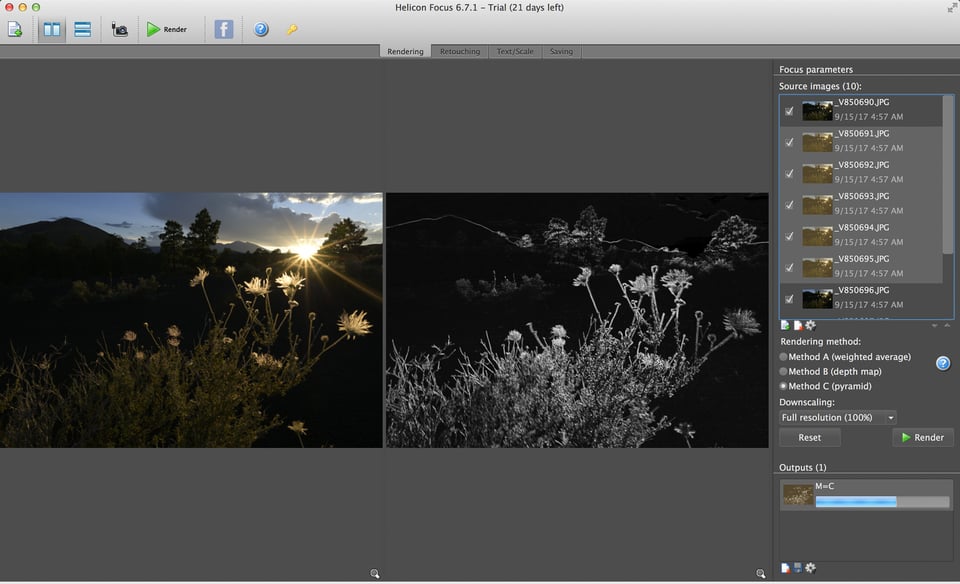

I downloaded the Helicon Focus 30-day trial the day I got my D850. Having never used it I watched a thankfully quick video tutorial and was up and running in minutes. The layout is much slicker than Zerene Stacker (which looks like hasn’t changed since the Pleistocene) and all you need to do is drop your files on the screen choose which algorithm you want and hit the render button.

Helicon Focus has three algorithms to choose from. My first try at the moth shot was with the B algorithm and results weren’t very good (this turns out to be the equivalent of DMAX in Zerene).

Note the blurry hiccup in the near antenna bend.

I retried in C mode and results were much better (this is equivalent to PMAX in Zerene).

Helicon Focus is much faster than Zerene Stacker and easier to navigate. As well it has the ability to work with RAW files and output a DNG that you can then take to Lightroom for nondestructive editing later. Helicon Focus also integrates with Lightroom so you can pick a group of photos out from Lightroom, left-click and export right to Helicon Focus, hit render and bingo.

If you pick the right algorithm for the subject, Helicon Focus results are good, but I feel Zerene Stacker is a tiny bit sharper. By “tiny bit” I mean you need to put your reading glasses on and zoom in to 100% to see a difference. Zerene Stacker also seems to retain a bit more shadow detail and color fidelity in pyramidal (PMAX/C mode) stacked shots. It will be interesting to see how Helicon Focus handles the D850 RAW files when they are supported. For its ease of use, speed and RAW capabilities I favor Helicon Focus now, but if Zerene Stacker would support RAW I would probably choose it for images I wanted to display large.

Here’s our lacewing again stacked in both Zerene and Helicon for comparison. Note the Helicon version (bottom) is a bit more contrasty and the Zerene version (top) is retaining a bit better color and shadow detail.

Helicon Focus also has an option to check every second or third shot in a stack to speed things up if your stepping distance was narrower than needed.

Both Zerene Stacker and Helicon Focus have retouching modes where you can clean up various image defects by cloning desired details from a chosen single frame in the stack. This is very useful but beyond the scope of this getting started article.

Zerene Stacker retails for $89 – $289 depending on the version. Helicon Focus will set you back $115 – $240 depending on the version, or you can get yearly licenses for $30 – $65. This software ain’t cheap, but neither is the Nikon D850. Search around a bit on the web and you might find discount codes for the stacking software or exorbitant price hikes on the back-ordered-on-arrival D850.

Focus Stacking vs Tilt-Shift

Tilt-shift lenses allow one to change the plane of focus essentially tilting it near to far to get close and far objects both in focus. If the subject aligns in a plane, for example, a mud-cracked playa receding to infinity, then tilt-shift lenses handle it well. Another bonus is once set up and aligned, you only need one exposure so you can shoot moving objects. If the subject does not line up in a plane – say you are shooting through a forest with near to far subjects randomly dispersed throughout the composition – then all the tilting in the world won’t bring every detail into focus. This is where focus stacking works better, however, it requires a static subject. If it’s a windy day and branches and leaves are moving forget focus stacking. As well, focus stacking only works as well as the software, so issues with haloing, ghosting and the like can occur.

As this tree root emerging from the cinders lies along a plane and doesn’t move in the wind, it’s an ideal subject for either focus stacking or a tilt-shift lens.

Focus Breathing and Macro-Rails

Focus breathing causes the subject size to change relative to the frame as one refocuses a lens. This, of course, happens when focus stacking with the D850. In general, the stacking software handles this well. For more critical stacking macro-rails are used. These allow one to focus once and then instead of refocusing between shots, one moves the camera along the focusing rail by turning a gear (or some set-ups move a stage the subject rests on). This eliminates focus breathing but takes quite a bit more effort to set up and execute than using the D850 focus stacking feature.

Other Tips

Make sure that you have plenty of memory cards – focus stacking racks up the image count quickly and the D850 files are massive. The same goes for batteries. All those shots and refocusing chew through batteries. I got ~1500 shots from the EN-EL15a that came with the D850, which if you’re doing 100 shot bug stacks isn’t many.

Focus Stacking Summary

Focus stacking is fun again now that the D850 makes it so easy. It took me less than 10 minutes to set up and shoot and process my first stack and I’m new to the D850 and the Helicon software. However, it takes a lot of experimenting to dial in the settings.

It would be nice if someone would produce an app that would allow you to input starting point, end point and lens, and it would calculate how many steps of what width at a given aperture is needed. Until then, I’d suggest just setting focus step width to 5, f-stop to f/8 and let ‘er rip for unlimited depth of field. If you want to isolate a subject and keep the background blurred, open up your aperture. Update: such an app does exist – see George Douvos’ wonderful Focus Stacker software.

Note that there are third-party software programs that will focus shift other models of cameras, but these require tethering to a computer or Camranger or another device. Just one more step in the process.

Table of Contents