Nikon D500 Review: Ergonomics

The D500 has some welcome additions to control points that are mostly reflections of what is seen on the D5. Probably most significant is the auto-focus joystick that Nikon calls the sub-selector, not to be confused with the standard circular multi-directional control that Nikon calls the multi-selector. The sub-selector is primarily intended for focus-point selection and its position adjacent to the AF-ON button, and right next to where your thumb rests, makes for fast and easy adjustments, especially when compared to the alternative which is to reach down for the multi-selector. We also have a couple of extra buttons: the Fn2 button on the bottom left of the camera back, and the ISO button on the top panel next to the shutter release.

Great stuff! More buttons are good, right? Only if you can use them. For some strange reason, it was decided that the Fn2 button should be restricted to only three possible functions. Two access the My Menu user customize-able menu in different ways, and the third is for assigning a star rating to images. I find this seemingly arbitrary restriction on button assignment infuriating. The Fn1 button on the front of the camera has a list of 24 possible functions assignable. Why not Fn2 as well? The addition of a dedicated ISO button to the top panel will make a lot of people happy.

For a long time on Nikon cameras, it was not possible to change ISO with the right hand while gripping the camera, and the left hand would normally be out in front supporting the lens. The ISO button solves that problem. Only the problem had already been solved some time ago when Nikon allowed us to reassign the movie record (red dot) button to ISO. This was great. It worked. So why solve the same problem a second time? And annoyingly, the ISO button cannot be reprogrammed. Now I realize almost everybody will want to use the ISO button as is, but I cannot see a reason for not allowing all buttons to be reprogrammed to the user’s taste.

There are a number of features of the D500 body that remind one of a high-end FX body and give the feeling of using a truly professional-grade camera. The round eyepiece with a built-in shutter is an example. Another is the 10-pin remote terminal that means your FX body accessories, such as cable release, will plug straight into the D500.

A minor annoyance is the small diameter multi-selector pad. Because of the small size, it is more difficult to use than the larger version on the D810. It looks as though the size is dictated by the fact that the tilting screen has quite a wide frame that occupies a fair amount of real estate on the back of the camera. I recently picked up a Pentax K-1 for the first time and noticed how thin-framed that camera’s tilting screen is, so I know it’s possible for Nikon to do better in this regard.

A very nice new feature (for a non-D4/D5) is back-lit buttons. It’s another obvious reflection of the D5, but something that I think Nikon could have easily gotten away with not implementing on the D500. Bravo Nikon for going the extra mile and giving us this very handy feature.

And finally, of course, we have the tilting touch-sensitive rear LCD panel. The panel tilts through a range of approximately directly down to directly up but cannot be completely flipped over so as to face forward and nor does it swing left or right. This is the same as the tilt screen on the D750. The tilting mechanism seems quite robust and the panel clips neatly into the back of the body when not tilted. I don’t have any immediate concerns about this being a weak point of the camera although it’s unclear how much it affects the degree to which the camera is weatherproof.

Along with tilt comes touch and I have to say that this was a pleasant surprise for me. I’m not sure how much I will use it, but the touch screen is responsive and works pretty much like a smartphone. For some reason, I was expecting a sluggish and unresponsive touch interface that would serve as a checklist feature but that nobody would actually want to use. I’m glad to be wrong about that.

While touch control does not extend to the menus, it is active for image review and live view. In image review, swiping left or right works as expected, taking you to the next or previous image. The direction of travel can be customized in the Setup menu, where there is also a global on/off switch for all touch control. Sliding a finger along the bottom of the screen provides fast scrolling through all images as an alternative to swiping an image at a time.

A double-tap on an image will zoom in at the point tapped. This is different from using a button for zoom (e.g. multi-selector center button) which zooms to the focus point of the image. Sliding a finger on the screen pans the image when zoomed. Pinch-zooming in and out is also possible. The subtle detail is that pinch-zooming in will automatically stop at 100% magnification, which is exactly what it should do. A second pinch gesture will zoom past 100%.

In live-view, we get tap to focus and, optionally, capture an image. Tapping on on-screen icon cycles through no-touch, tap-to-focus, and tap-to-focus and image-capture. It’s possible to use live view touch in combination with Exposure Delay and Electronic First-Curtain Shutter. So then a single tap on the screen will focus at the point tapped, initiate image capture, wait for (up to) three seconds and begin the exposure with no mirror or shutter movement. Very nice! Bizarrely though, you still need to have the release mode dial set to mirror-up to enable the electronic shutter, even though you’re in live view. That must make sense to someone at Nikon but it doesn’t to me.

High-DPI LCD Screen

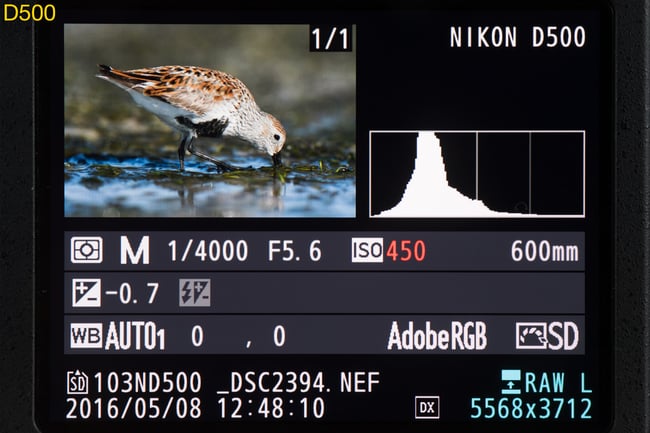

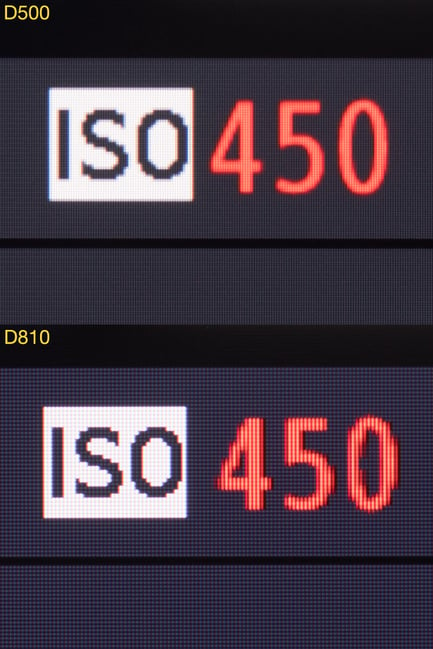

Not everyone will use the tilt and touch features of the LCD screen, so the most significant upgrade there, versus other current Nikon models, might be the resolution. The screen is 2.36 million dots, which turns out to be 1024 x 768 pixels at 3 dots (RGB) per pixel. For the 3.2 inch (diagonal) screen that’s 400 pixels per inch, which is right up there with high-end smartphones. The previous high-end spec for Nikon DSLRs was 1.23 million dots, 640 x 480 pixels at 4 dots (RGBW) per pixel, 250 pixels per inch. So it’s quite a big jump in resolution. The white sub-pixel (the W in RGBW), which I believe was supposed to help to view in bright light, is gone. But is it really an upgrade?

I spent a little time comparing the D500’s screen to the one on the D810, expecting it to be better in every way. I was surprised by what I found. The pictures below tell the story:

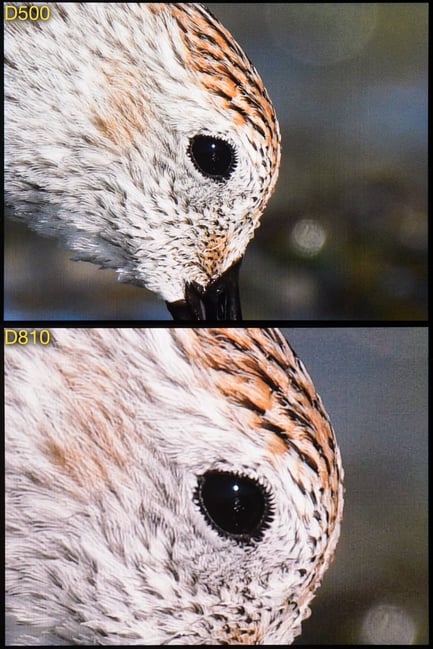

The resolution difference is obvious when looking closely, though not really at normal viewing distances. But when reviewing an image and zooming to 100% to check sharpness, I realized that the higher dpi of the D500’s screen may not be an advantage, but rather the opposite. Because of the greater pixel density, the magnification is actually less when viewing one image pixel per screen pixel.

Which of the above images is sharper? To me, the image on the D500’s screen clearly looks sharper, but in fact, they are the same image. The same image file is displayed on the two cameras zoomed to 100%. The D500 looks sharper only because the pixels are smaller. I have been using a MacBook Pro with a high-dpi “Retina” display for a few years now and it looks great, but it is not ideal for image editing due to tiny pixels. It is difficult to judge sharpness and I much prefer a lower resolution screen when performing sharpening and noise reduction. The same problem here. It is possible to zoom past 100%, but it’s pointless because then you’re looking at an interpolated picture and you cannot reliably judge sharpness.

Above is a comparison of screen brightness between the D500 and the D810. The pictures were taken outside on a bright sunny day. Both cameras were set to maximum brightness. In the top pair of images, the screens are reflecting a bright blue sky. In the bottom pair, a black shirt shielded them and cut the reflection. In both cases, it’s obvious that the D810 screen is brighter and has a higher contrast.

And it’s obvious to the naked eye, not just in these pictures. I can also say that at the minimum brightness setting, the D810 is dimmer. So it is both brighter and dimmer and has higher contrast. Perhaps the W in RGBW was important after-all! Hey, it’s not the end of the world. But it is a step backward, apparently required in order to gain touch capabilities. Was it worth it?

One last thing has me scratching my head. The sample image of the Dunlin shows a small number of “blinkies” (overexposed pixels) on the D810 but not on the D500. Huh? Remember, this is the same image on both cameras. It’s the same RAW file with the same embedded JPEG image. Why does one camera show over-exposure and the other does not? Please explain.

Nikon D500 Review: Autofocus Performance

Probably the headline feature of the Nikon D500, other than its very existence, is the brand new Advanced Multi-CAM 20K auto-focus module which is touted by Nikon as “a new era of auto-focus”. This is certainly not just an incremental improvement on the previous generation. With great strides being made elsewhere in on-sensor auto-focus capabilities, it seems Nikon engineers decided to show us there are still gains to be made with traditional off-sensor phase-detection focusing. The new AF system will go some way to maintaining the performance gap between DSLRs and mirrorless cameras.

A total of 153 focus points stretch horizontally to the edges of the frame. The vertical coverage is still just a little limited, however. I have often found myself wanting to trade in a few of those points at the extreme left and right for some more above and below. But overall, the sensor coverage is a big step forward. 55 points are user-selectable with gaps filled by points engaged as needed by the focus module in any of the subject tracking modes.

On my first trip into the field with the new camera, the immediate impression was one of speed. Focus is very snappy. Soon I noticed a small problem. It may actually be a little too sensitive and jumpy. With default settings for Focus tracking with lock-on (Custom setting a3), I was often losing focus to a point behind or in front of the subject. But it was reacting so quickly, that I could almost ignore it. As fast as it lost the subject, it was back again. So, of course, I started messing around with the Custom a3 settings trying to find the sweet spot. Have not found it yet. I look at this as a period of adjustment and learning. It’s like having a new high-performance sports car and having to refine your driving skills to get the most out of it.

Tom Redd and I each had several weeks of shooting with the D500 before getting together to compare notes. Autofocus performance is mostly what we talked about. Here is what Tom had to say:

The Nikon D500 autofocus was the one feature that I was most excited about, with the ISO capabilities running a close second. I hoped the new 153 point AF system would live up to my anticipated expectations. Oftentimes, photographers’ anticipated expectations are too great to be realistic, as may have been the case for the low light/high ISO abilities of the D500. Leading up to the launch date of the D500, many forums were discussing the high ISO abilities of the D500 and the expectations were all over the board and often placed way too high to be realistic. While the low-light capability of the D500 has pleased me, it hasn’t been as insanely good as some were predicting and/or hoping for.

Let’s get back to the autofocus. While I could have sky-high hopes for an AF system that never misses, it isn’t realistic. What I can say in short, is that the new AF system in the D500 does not disappoint and it is the best AF system that I have shot with so far. I haven’t shot with the big brother D5, but they share the same system. I will share some thoughts and as I do, please keep in mind that these are just that, my thoughts. Your experience may be different and ultimately, what works best for you is what you will use. I have had to take some time to try different AF modes from previous cameras.

While 3D is improved, I haven’t found it to be as great as other reviewers have. It still is slower than the other modes to lock on initial focus and that bothers me. I use 3D most when the subject movement is predictably coming straight at me. Otherwise, I prefer modes that are faster to acquire lock-on. To be fair, I may not have used this mode on the D500 enough to say otherwise, but this is my impression so far.

When it comes to Dynamic Area, I have found these settings to be a bit of a mixed bag. I use 9-point AF on my D750 and D4 more than other settings. On the D500, 9-point AF is replaced by 25-point AF and it has been a little more challenging than I expected. What I find is that the 25 point AF setting does more searching. When the center point is on the subject, the camera often quickly will jump into the foreground or background and back to the center point – it is quick, but it hunts.

I didn’t experience that as often with the older 9-point AF setting. I have used the D72 and D153 when a bird is perched and I am awaiting a takeoff shot. It seems to track well since the initial focus is already acquired. I don’t personally use Group or Auto much. They might be wonderful, but since I don’t use them much, I can’t speak to them. In the past, I have used Group Area AF a little, but never felt that it was all that great in my hands. I know others love it, and so to each his own.

A pleasant surprise is that I find that I use a single point focus in AF-C mode more than any other setting. This was unexpected and replaces my 9 point setting as my go-to setting. I have been surprised at how well this camera focuses and tracks with a single point focus and it isn’t my tracking ability because my focus point isn’t always staying put on the subject as it moves. I miss the subject plenty and yet the camera has stayed locked-on and tracked well, even when I wouldn’t have expected it to.

I want to mention a word or two about tracking a subject such as birds in flight, while using a burst. One thing that I notice when shooting bursts in continuous high mode, is that I seem to have more black-out time than with the D4. Both cameras have essentially the same frame rate at 10 fps, and yet the black-out time between shots seems noticeably longer with the D500 than the D4. This black-out period makes it a bit more challenging to track a bird in flight than with the D4 or D4s. I thought it was me and when discussing this with John, but he was as surprised as I was to find out that we both had come to the same conclusion. I’m not sure if it’s me, an illusion, or if it’s real, but it feels real to me and that might be a small niggle in what is otherwise an excellent camera.

I am finding that I have far fewer missed shots than with any of my previous Nikon DSLRs. The difference is hard to place a number to, but I can say this, it is not a small or incremental difference. The difference is significant. Overall, the AF system of the D500 is so good that I find that I grab the D500 over the D4 in almost every instance. The D4 still has the edge in the low light/high ISO department as far as I’m concerned.

I find it interesting that Tom and I have had such similar experiences and noticed so many of the same things that set the D500 apart from other Nikon cameras. It looks like Nasim pretty much shares the same thoughts after using the Nikon D500 for a couple of months. We are all still learning the new AF system and I wonder if in the end we come to the same conclusions about how best to utilize the AF for shooting wildlife, or if we come up with different solutions for the same challenges.

Before even getting my hands on the camera, I had dreams of setting 3D-tracking mode and having the subject magically tracked all over the viewfinder without having to chase it with the focus point joystick. While the new tracking abilities probably are significantly improved they are unfortunately still nowhere near good enough for reliable tracking of fast and unpredictable movement. You may be focused on the eye of a bear but then it turns its head to the side and the camera sees fur. And fur on the head looks like fur on the shoulder and the back and the leg. And so manual intervention is required to get back on target. I’m frequently amazed at what modern auto-focus systems can do, but I am just as frequently reminded of how fallible they still are.

The new auto-focus system is different enough from the old that I think it is worth dropping all assumptions about how to use it and then reassessing all the different focus modes and how they might fit a given shooting style or subject. For myself, I am considering the 153 point mode and maybe even auto-area in certain cases. The tried and true D9 (now D25) may not be the way to go any longer. Time will tell.

Nikon has a D500 tips page with in-depth information on camera settings that goes beyond what is found in the user manual. In particular, there is an extensive section on recommended autofocus configurations when applied to a range of sports. It’s worth taking a look at this document to get a sense of how the new auto-focus system is supposed to work.

Automatic AF Fine-Tune

Automatic AF fine-tuning is an eagerly anticipated feature made available for the first time on the D500 and D5. It promises to take a tedious and error-prone process and make it quick and easy. Manual AF fine-tuning has been available on many DSLRs for years (see Nasim’s detailed article on how to calibrate lenses with AF Fine-Tune). It allows for manual calibration of the auto-focus system to account for slight differences in the distance light travels to the focus module at the bottom of the camera as opposed to the focal plane at the back of the camera.

Manufacturing tolerances are such that there will always be some amount of misalignment which results in front or back focusing. In many cases the imperfect focusing is not noticeable but in some cases it is and you end up with consistently out of focus images. To date, the process for manual calibration involves either taking a series of test shots against a target and eyeballing them to try and determine which has best focus, or tethering your camera to a computer running special calibration software and again shooting a test target.

Only this time the computer does the eyeballing for you. The first method is prone to error and both are slow and tedious. Nikon’s automatic AF fine-tune, on the other hand, involves simply picking a flat, well-lit, high-contrast and stationary subject, and focusing in live-view using contrast-detection autofocus. Because you are focusing on the image sensor, in theory, your focus at that point is spot-on. Then press a couple of buttons and you’re done. The calculated calibration value is stored in the camera’s memory. It is highly recommended to perform the test a number of times and go with the median value.

E.g. I calibrated the D500 with my Nikkor 600mm f/4G VR lens. Test was performed six times with the following results: +4, +4, +3, +2, +3, +4. I went with +3 although +4 or even +2 would have been acceptable. You would not notice the difference between a point or two.

How does it work? I have not seen an official explanation of what is going on under the covers but I think it is a rather simple process:

- In live view mode, focus is achieved on the focal plane (sensor) by the user.

- The mirror flips down so the phase detect AF module can view the scene.

- The phase detect AF module calculates how far out of focus it thinks it is but does not refocus the lens. The nature of phase detect auto-focus is such that it can determine the direction and distance required to achieve focus. Because we already have correct focus, whatever focus adjustment it thinks is required is actually the amount by which it is in error.

- This error amount is translated into an AF fine-tune value and stored in the camera. It will be applied any time that camera/lens combination is in use.

The clever thing about this method, is that once initial focus is achieved, there is no further focusing required. The phase-detect module only passively reads the scene, but does not initiate focus itself. There is no need of a special test target and no image capture and analysis is required. It is quick and simple, and reliable enough to be done on the fly in the field, if necessary.

However, there is one “gotcha” with this method. As discussed in a number of articles written at PL, AF Fine-Tune has a number of huge limitations – calibration only works for a particular distance and there is no way to save different values for different focal lengths or distances when calibrating zoom lenses.

Continuous Shooting

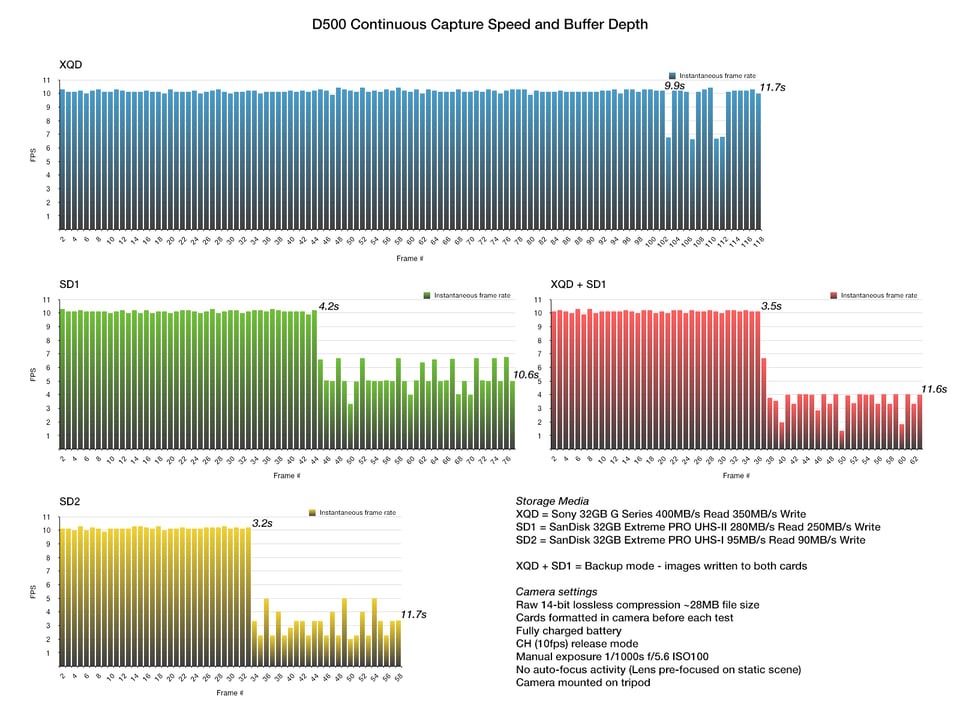

It sure is nice to be back in the fast lane. In recent years, I’ve been getting by with a capture rate of 4 or 5 frames per second, knowing that I am missing shots or at least missing out on being able to select the optimal moment from a burst of action because it occurred in-between captures. The Nikon D500 sure helps with that problem. One simple question led me to conduct a bunch of testing on the frame rate and buffer depth of the new camera. I like the idea of setting backup mode for image storage. That is where images are written to both cards as they are captured. If one card goes bad, you have a backup. But I wanted to know how much of a hit I would take in terms of time to clear images from the buffer and allow continuous shooting at maximum speed.

Under ideal conditions, the camera will push above 10 frames per second, but I was not able to get close to 200 shots before the buffer filled. The best was around 100 as shown on the chart when writing to the XQD card. The fast UHS-II SD card fell well short of the XQD as shown here, although in other tests the difference was not so large. The red chart tells me what I really wanted to know.

When writing to both a fast XQD and a fast SD card, the performance is not too far short of writing to SD alone. That is 3.5 versus 4.2 seconds of full-speed shooting, which is plenty for almost any situation. When I first got my hands on the D500, I had no fast cards, just a UHS-I SD card from my D810. I started shooting with it and weeks went by before I thought about getting anything faster. You can see how the “slow” SD card performed on the yellow chart. It’s full speed for more than 3 seconds. After that, the frame rate plummets. But in a month of shooting, I never did hit that wall. Meanwhile, the cost of XQD cards was also plummeting ;-)

There are a huge number of factors affecting frame rate and buffer clearing performance. If you ran your own tests, your numbers would likely be different. Things like scene complexity (affecting file size), ISO and the brightness of the scene, and many other things will affect the outcome. In some of my tests, I could barely get above 9 fps and I think it may have simply been because of a darker scene requiring a higher ISO. But the tests presented here show that the camera can certainly capture at least 10 frames per second and also that the buffer is very large, but has real limits.

Viewfinder Black-out

One of the stand-out features of the D500 is the high continuous capture rate, up to 10 frames per second (along with a huge buffer so that speed is actually usable). For too long the only really high-speed Nikon DSLR has been a high dollar flagship model. The D300 with grip could do 8 fps which was great, but that was a long time ago. The missing speed in recent years is one of the prime reasons so many longed for a proper D300 replacement.

Nikon certainly did not disappoint in that area with the D500. Oh what fun it was that first morning out with the new racehorse, firing off high-speed bursts at anything that wandered in front of my lens, not because I needed to but just because I could. Yes, speed is addictive. But once the excitement began to wear off a little, I noticed something. Running the D500 at 10 fps I found pretty significant viewfinder black-out, which was especially apparent when shooting a moving subject.

In particular, a fast and erratically moving subject, where tracking is a challenge even under the best of conditions. How much of a problem was it? I would say just enough to make me wish for a little more viewing time when in the middle of a burst, but not enough to stop me shooting that way. Interestingly, Tom Redd later told me he had similar thoughts about shooting the D500 at top speed. We both felt that the viewfinder black-out was significant and right at the edge of being a problem. At that time I had not shot with a D5 but had read that the black-out on that camera was impressively short. I wondered how the two would compare. I have not seen an official number quoted for either camera and so decided to make my own measurements.

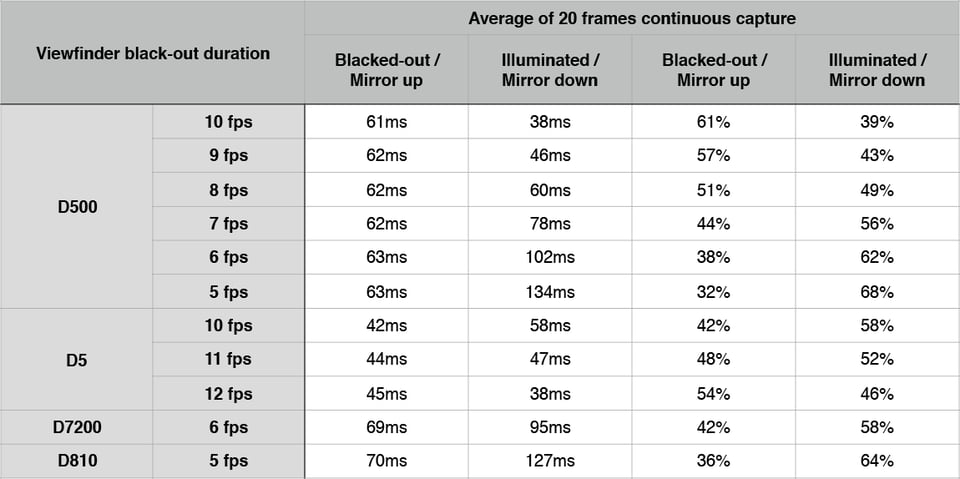

My testing was done with an iPhone 6s recording video at 240 fps and positioned close behind the camera’s eyepiece giving a clear view through the viewfinder. At 240 fps, each frame of recorded video is a little over 4 milliseconds. That’s not enough resolution to give a really accurate number for viewfinder black-out duration, but I think it’s good enough for an approximation for the tested camera and for comparisons between cameras.

My main interest was a comparison of the D500 and D5, but I also had a D7200 and D810 close at hand and so I decided to include those as well. Several seconds of video was recorded with each of the cameras firing at various speeds. Each clip was then reviewed on a desktop computer, stepping through the recordings frame by frame and counting the number of frames where the viewfinder was clearly illuminated and the number blacked out. The results are summarized in the table below.

Disclaimer: Don’t take these numbers as gospel. Manufacturers will have their own methods for measuring. They probably don’t use iPhones! I would expect official manufacturer numbers to be different. But my test results were very consistent with low variability which gives me confidence that they have some validity. At the very least they should be good for comparative purposes because all the cameras were tested the same way.

Here is what I learned:

– Tom and I were not imagining things. At 10 fps, the D500 viewfinder is blacked out most of the time. It’s about a 60/40 split, blacked-out versus illuminated.

– The D5 does much better at 10 fps. In fact, it flips the split to about 40/60, blacked-out versus illuminated.

– Even at the D5’s top speed of 12 fps, it still has less overall black-out time than the D500 at 10 fps.

– You need to slow down the D500 to 7 fps to approximate the D5 at 10 fps.

– The D500 at frame rates 10 through 5, the black-out time was quite consistent and averaged about 62 ms. Black-out time per frame increased slightly at lower frame rates although overall black-out time went down as you would expect.

– The D5 went the other way. At 10, 11 & 12 fps the per-frame black-out time actually increases at the higher speeds. That doesn’t make much sense to me but that’s what the numbers say. The D5 averages in the low 40ms range for black-out duration.

– The D500 has about 50% longer black-out time than the D5. Now you know where the money goes, some of it at least.

– The D7200 and the D810 both have about 70ms black-out times, but because of their relatively slow frame rates, it’s not an issue.

So is this really a problem? Many will never notice I’m sure. And of course, the option is there to select a lower frame rate if needed. Less frames per second means more mirror-down time and more “seeing”. 10 fps is overkill in many cases anyway. But it does highlight a potential area for improvement in the future. Perhaps a successor to the D500 may get down into the 40ms range of the D5. That would most certainly be welcome. There’s something else…viewfinder black-out time also means auto-focus black-out time. Both the D500 and the D5, at top speed, seem to have only about 38ms between frames to do their auto-focus magic. Remember that AF just got faster, smarter, more accurate – now with less time to think and act. It just makes the new AF system look even more impressive.

Best Lenses for Nikon D500

There are countless lenses that are compatible with the Nikon D500. After all, Nikon’s F-mount has been a standard in the photography world for decades. But only a few make our top-of-the-top recommendations for the D500. Here they are:

1. Nikon 300mm f/4 and 500mm f/5.6 PF Lenses

Two lenses share the #1 spot here: Nikon’s 300mm and 500mm phase-fresnel (PF) lenses. Quite simply, these are two of the best telephoto lenses ever made.

What makes these lenses so special? They’re lightweight, relatively bright, and very fast to focus on the D500. Their sharpness numbers are through the roof. They also have very useful focal lengths for sports and wildlife photography on the D500 (offering full-frame equivalent focal lengths of 465mm and 775mm).

The 300mm f/4 PF costs $2000 new, and the 500mm f/5.6 PF costs $3600 new. So, they’re not the cheapest lenses, but they’re much less than an exotic supertelephoto. Both are perfect for capturing distant action on the Nikon D500.

Which one of the two lenses is better? Or should you just get both?

I don’t think you need both. Instead, figure out how much reach you need. 300mm is a good focal length for bigger or closer subjects, whereas 500mm is ideal for small, distant wildlife. I suggest the 300mm f/4 if you’re a sports photographer and the 500mm f/5.6 for wildlife.

Note that both lenses are compatible with teleconverters. If you intend to go this route, the combo I recommend is the 300mm f/4 with Nikon’s 1.4x teleconverter, which gives you a 420mm f/5.6 lens.

2. Nikon 16-80mm f/2.8-4

This is the best midrange zoom that Nikon ever made for its DX DSLRs. It covers an extremely useful

3. Nikon 50mm f/1.8G

4. Tokina 11-20mm f/2.8

5. Nikon AF-P 70-300mm VR (Either Version)

Nikon makes two 70-300mm lenses with an AF-P motor and vibration reduction. One of them is a DX lens (the 70-300mm f/4.5-6.3 VR DX) and one is an FX lens (the 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6 VR).

Both are excellent choices on the Nikon D500. They cover a very useful range of focal lengths and are impressively lightweight. But which one should you get? There are three differences that matter:

- The DX lens is less expensive (about $400 vs $600 new)

- The DX lens weighs less (415 grams vs 680 grams, AKA 0.9 pounds vs 1.5 pounds)

- The DX lens does not cover any Nikon full-frame camera

Although there are minor differences between them in image quality and handling, those are by far the most important points. Are you willing to pay more and carry a heavier bag in exchange for a lens that is also compatible with Nikon’s full-frame cameras?

Photographers who only ever shoot with the Nikon D500 will be fine with the DX lens. However, anyone who expects to buy a Nikon FX camera one day (either to replace or supplement the D500) should get the FX lens, so that it works on all their cameras.

More Lens Recommendations

You’re in luck! As part of our continuing coverage of the Nikon D500, we’ve written a complete guide to all the lenses we recommend for D500 users. This guide has longer comparisons and detailed sharpness results from a wide range of lenses. You can read it below:

Table of Contents