Lens Sharpness, Contrast and Color Rendition

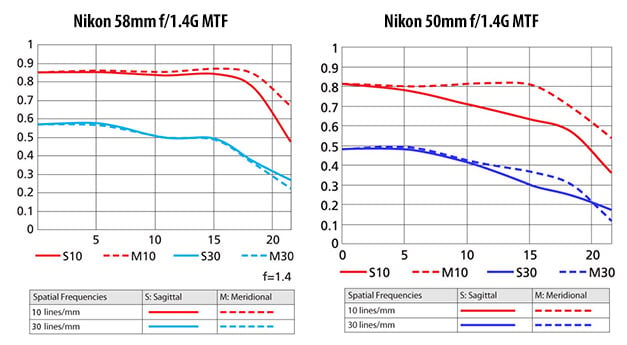

When the Nikon 58mm f/1.4G lens was released, Nikon specifically pointed out that the lens was of a different optical design, one that was not concentrated on sharpness alone. The 58mm f/1.4G was optically optimized to yield a three-dimensional look with beautiful bokeh and that’s its main selling point. Through these words, Nikon wanted to point out upfront that one should not expect to see tack-sharp images that we are so used to seeing on such expensive and exotic lenses, but rather concentrate on aesthetics. After I looked at the MTF chart of the lens initially and compared it to the 50mm f/1.4G, I came to the conclusion that the lens would be a little sharper than the Nikon 50mm f/1.4G and would have more consistent performance across the frame, with better corners. Here is the comparison of the MTF data between the two:

Please see my detailed guide on how to read MTF charts if you need some guidance with understanding the above.

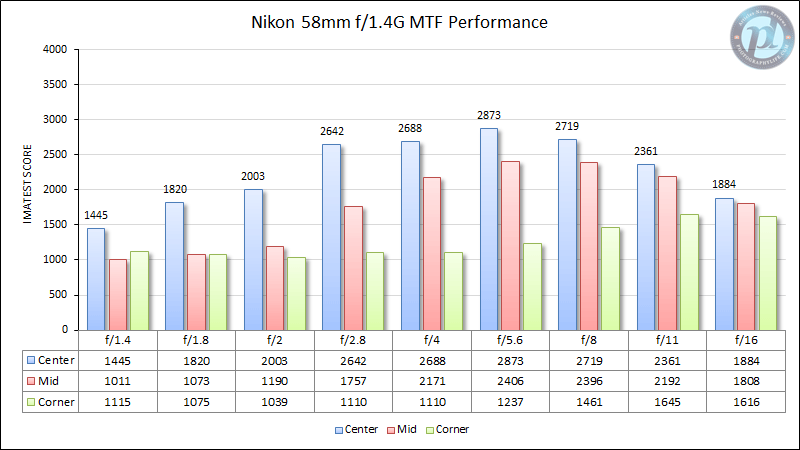

As I have said a number of times before, MTF charts provided by manufacturers are mostly simulated and do not represent the real picture. In addition, such simulated tests typically show performance at infinity, which is not very valuable, especially when looking at macro and portrait lenses that are rarely ever used at infinity. In the case of the 58mm f/1.4G, the above MTF does not show its biggest optical issue – curvature of field at short distances. As you can see from the below Imatest chart, the Nikon 58mm f/1.4G yields pretty good sharpness in the center, but its mid-frame performance is not good – worse than the corners at close range. The big reason for this is the wavy field curvature of a “sombrero” type, where the center is sharp, mid-frame falls off quickly and the area towards the corners pick up again. As you get closer to the subject, the curvature changes in shape and it negatively affects the corners, making them appear even softer. Take a look at the below sharpness test results:

As you can see, there is a huge difference in performance between the center frame and the rest of the image. At the maximum aperture of f/1.4, the wavy / sombrero field curvature is pretty evident, since the corners are sharper than the mid-frame. As the lens is stopped down, the effect of the field curvature diminishes significantly and the mid-frame picks up to good levels at f/2.8. By f/5.6, the mid-frame reaches excellent levels. However, the extreme corners never really improve to good levels, even when stopped down to f/8.

A very important fact to point out here, is that the above test was captured at a distance of about 11 feet. As I have indicated above, the field curvature issue of the 58mm f/1.4G actually worsens at closer distances. As you move away from the subject, the effect of field curvature diminishes and gets to acceptable levels towards infinity, which explains why the MTF chart looks pretty consistent. Unfortunately, it is impossible to test lenses at infinity using test charts – they are simply not large enough to handle such distances. An expensive optical bench setup is required to see what the lens is capable of achieving at infinity.

What does this all mean? Does it present a huge problem for photographing portraits or the night sky? No, not really. Field curvature is not always a bad thing. It simply means that the lens cannot bring everything on the flat plane into focus. In the case of the 58mm f/1.4G, the subject that you focus on will be very sharp, but the area around the subject on the same plane won’t be. So if you need to photograph something flat, like a picture or a painting at distances closer than 15 feet, the area where you focus will be sharp, but everything around it will be blurry.

Hence, this lens is obviously not a good candidate for that type of photography. However, if you photograph people, you will rarely ever notice the effect of field curvature, because you will be concentrating on a single area to bring into perfect focus. In fact, this optical issue can be an advantage for portraiture, as it effectively helps to blur the outside area even more. As reviewers, we tend to praise lenses that perform well in the corners and do it even for portrait lenses, over-emphasizing something that actually often does not matter for portraiture. I am guilty of this myself! There are some great lenses out there that do not do well in tests, but yield very pleasing images. A number of Zeiss and Leica lenses fall into this category.

If you are wondering what sharpness looks like at pixel level at f/1.4, take a look at the below 100% crop from the Nikon Df camera (unsharp mask applied in Photoshop):

The above crop is from the same image of the model from earlier. As you can see, the detail level one is able to get from the lens is very good. You just have to make sure that you focus accurately on the subject. The Nikon D800 does not yield the same sharpness at pixel level, but it is still plenty enough for most needs.

Another important factor that you need to keep in mind, is that field curvature affects the image differently depending on where you focus. In the above case, the lens was focused in the center. If you were to focus in say mid-frame, then the mid-frame would appear sharp, while the center and the corners would lose their sharpness. So when you see such poor corner performance in lenses with field curvature problems, the corners are not necessarily as bad as depicted in these charts. Some reviewers focus in the corners separately from the center or mid-frame and provide such results, but I always only focus in the center of the frame. If I were to employ the same practice of focusing in different areas, then Imatest numbers would look too good for all three and I would never be able to show optical issues such as field curvature.

What about astrophotography? Well, since the field curvature issue on the 58mm f/1.4G is greatly diminished towards infinity, photographing the night sky at large apertures should not be a problem. I would recommend stopping the lens down a little to yield maximum sharpness – even f/2 will make a huge difference.

Bokeh

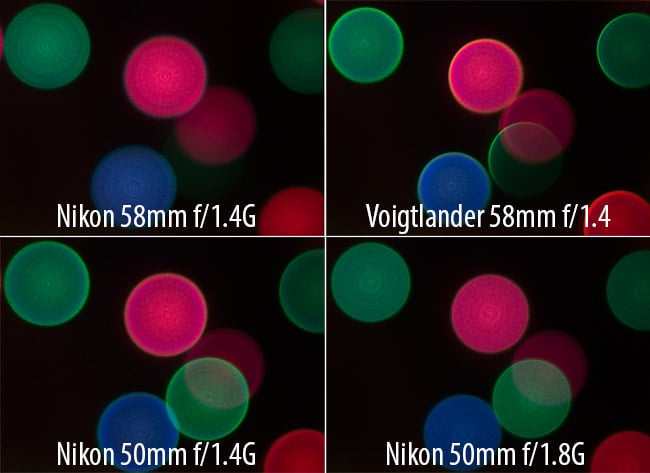

Bokeh is a very important characteristic of the Nikon 58mm f/1.4G lens and one of its main selling points. As you can see from the many image samples in this review, the lens has exceptionally good subject isolation capabilities and beautiful bokeh. One of the main requests that I have been getting from our readers, has been to compare bokeh performance between the 58mm f/1.4G, 50mm f/1.4G and 50mm f/1.8G lenses. Since I also have the Voigtlander 58mm f/1.4 lens, I decided to include it in the below comparison as well. Let’s take a look at how the four lenses compare at their maximum apertures:

When judging the quality of background highlights, it is often said good bokeh does not have well-defined rings around highlight shapes. In that regard, the Nikon 58mm f/1.4G definitely delivers – it practically has no rings and very smooth transition. This smooth transition is what results in exceptionally beautiful background rendition that transforms one background element into another. If the rings are too defined, it can lead to something commonly referred to as “nervous bokeh”, where background elements have sharper edges. Take a look at the below image that demonstrates the smooth transition of background elements:

From my experience, the only other modern prime in the Nikon line under 100mm that is capable of producing bokeh that looks this pleasing in images is the Nikon 85mm f/1.4G.

The second factor in bokeh quality is the cleanliness of the inner area and that’s where the Nikon 58mm f/1.4G suffers the most. Since the lens design includes aspherical elements, the inside of the highlight has a ring pattern known as “onion bokeh”, which can look rather distracting. Note that the Nikon 50mm f/1.8G also has these inner rings, because it contains an aspherical element as well. Since the 58mm f/1.4G has two aspherical elements, its onion rings are more defined than on other lenses in the group. Please note that these onion rings are only typically visible in very bright circular background highlights. They are never visible when looking at out of focus areas or when the out of focus highlights are less bright. Take a look at the below photographs of Christmas lights, where onion shapes are practically invisible in highlights:

Please keep in mind that the above comparison only shows one side of bokeh, which is just defocused highlights. I highly recommend to refer to the many image samples used in this review for understanding the bokeh characteristics of this lens.

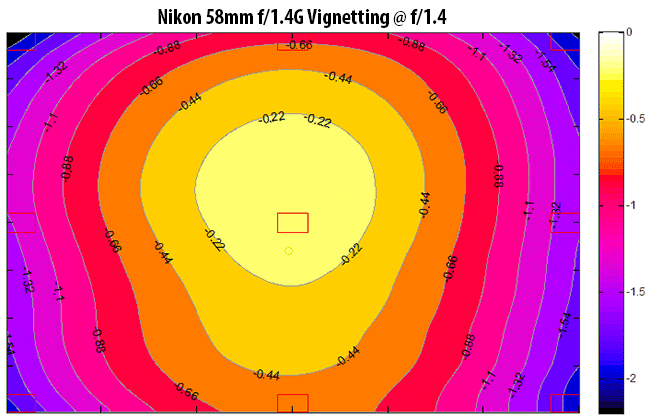

Vignetting

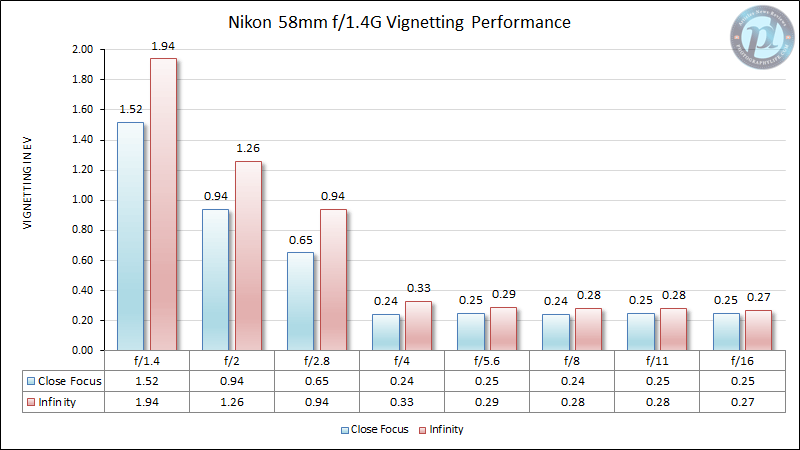

Nikon also specifically pointed out that the 58mm f/1.4G has very low vignetting levels. Let’s see what Imatest was able to measure at different apertures:

Indeed, vignetting levels are fairly low for this lens, but not by a significant amount. While there is some visible vignetting wide open between 1.5 and 1.9 stops depending on subject distance in the extreme corners, it drops significantly at f/2 and f/2.8. Stopped down to f/4, vignetting disappears almost completely and stays that way all the way to f/16.

Here is the worst case scenario, shot at f/1.4:

Ghosting and Flare

None of the Nikon 50mm lenses have Nano coating, so the 58mm f/1.4G is unique and the first of its kind in that regard. While Nikon says that Nano coating reduces ghosting and flare, over years I discovered that Nano coated Nikkor lenses also greatly enhance colors and overall contrast. This is especially true when working with back-lit subjects and high-contrast scenes. While Nano coating certainly reduces internal reflections, it cannot fully cope with direct sunlight, especially at longer focal lengths. When the light source is very strong, it is expected that some ghosting and flare will appear in images. To reduce direct exposure to the sun, Nikon already moved the front element deep inside the lens. Let’s see what happens with ghosting and flare when the lens is pointed directly at the sun without a lens hood (shot at f/8):

As you can see, the lens seems to handle ghosting and flares well, even when pointed directly at the sun. Stopping down to very small apertures like f/16 can introduce blue streaks of light at certain angles, but it is not a huge problem, since you can eliminate them by re-framing the shot or opening up the aperture. Shooting directly at the sun while taking portraits can yield results like the following:

Distortion

Unfortunately, the Nikon 58mm f/1.4G has a visible amount of barrel distortion. When photographing straight lines, it will be noticeable to the naked eye. Imatest measured a barrel distortion of 1.45%, which is pretty close to distortion on the Nikon 50mm f/1.4G (1.41%). In comparison, the Nikon 50mm f/1.8G suffers from less distortion at 0.93%, while the Voigtlander 58mm f/1.4 has the least amount of barrel distortion at just -0.60.

Is distortion a problem? No, not at all – it can be easily fixed in post-processing software like Lightroom and Photoshop without losing much of the original image. Adobe already has a built-in lens profile in the Lens Corrections module for the 58mm f/1.4G, so you can easily take care of the problem with a single click.

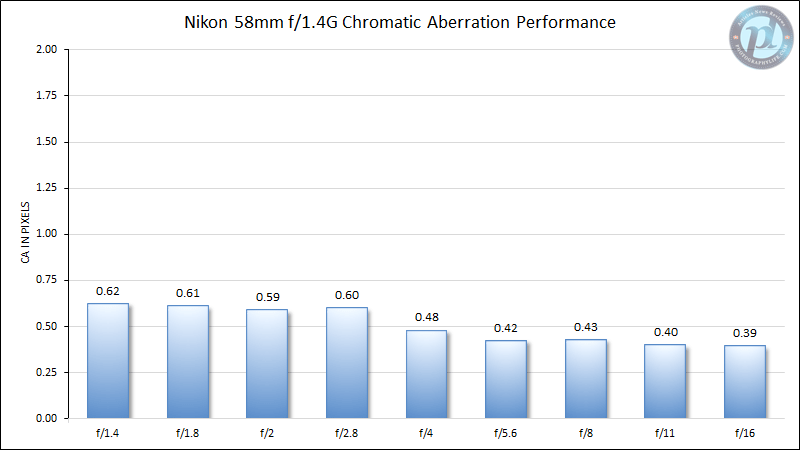

Chromatic Aberration

Lateral chromatic aberration is controlled very well, even in high-contrast situations. Below are the CA levels measured by Imatest:

Anything below 1 pixel is considered to be very good and the Nikkor 58mm f/1.4G surely does not disappoint here. Averaging around half a pixel, the lens outperforms both the 50mm f/1.4G and the f/1.8G lenses.

“LoCA”, or longitudinal chromatic aberration (which is the effect of color fringing in front of and behind the focused area) is very similar to what the Nikon 50mm f/1.4G yields, which shows a noticeable change in color in front and behind the focused area.

Let’s now move on to the good stuff – lens comparisons.

Table of Contents