With all the greatness, speed, quality and versatility of digital photography, it became irreplaceable in our everyday lives and businesses. Along with that, however, digital photography also brought up a few problems, likely the biggest of which was the growing interest in new technologies rather than photography itself. This problem seemed to push the very goal of having a camera and a lens completely out of our minds. The new gear was the thrilling, fun part. Comparing one to another has become our everyday activity.

And yet, if we manage to get past that, if we manage to actually get out there and shoot rather than just read and read and read about new lenses and cameras day after day, we get the point of digital. We get to enjoy it as we should. We get to see digital, in a way, how we see the 18-200 or 28-300 class lenses – the do-everything, good enough for anything, the daily choice. But here lies another potential problem – with all the great all-round lenses, why do we love those boring 50mm f1.4 primes so much? I find myself shooting, and shooting, and shooting again. I find myself having hundreds, if not thousands, of photographs, and I like them. But a super-zoom is no prime lens. There’s always something vital missing. I may have just found out what it was for me. Before we dive into my very personal and subjective review of the Mamiya RZ67 Pro, lets talk film for a minute.

A Couple of Thoughts on Film

Where digital is about speed, you had to take it slow, sometimes even painfully so, with film. Where you had the shot with digital the second you pressed that shutter, you had to carefully store, develop and enlarge the photograph back in the day. Fiddle with the chemistry and red light in complete darkness. And you had, at best, 36 shots before you take a break and change film, whereas with digital, you have hundreds and hundreds before you swap that SD/CF/XQD card and shoot away again, ten frames per second. And every shot had to count. For every exposure, you pay money. You had manual focusing and manual exposure (I’m not talking about automated SLRs – I find them a little too boring, and we’ll talk about it further on) and you never knew if you’d screwed something up in the process. With digital, you can just shoot, adjust, and shoot again. I’m not even going to start on dust and scratches and archiving and having copies and making sure you don’t expose that precious roll to light before you had the chance to develop it.

Now, if we’d be rational about this, film is obsolete. Digital, in every way, seems better… But. Remember Kodak? They are undergoing Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Protection, which means they must reorganize the company and make it stable again. Kodak closed several divisions, but there’s one that’s still, believe it or not, working. You guessed right – film. After a decade of technology sprint, new cameras every year, affordable and high quality of digital, photographers still buy film. Why?

The reason is very, very simple. It is the same reason people, while owning some of the newest, fastest, safest, most practical and fuel-efficient cars, love old classics, such as the Mercedes-Benz 230SL or a Mini. The same reason why people love the expensive Vespa scooters, why we secretly prefer hand-written letters to faster and easier to write emails. It is the same reason why we love family albums more than Facebook galleries, why we use our father’s old mirror when we shave, rather than a brand new one with an inbuilt wiper. It’s because sometimes, even if very rarely, we want to slow down. Sometimes, we want to enjoy the process as much as we enjoy the result. Yes, driving down to the mall in your VW Golf for groceries just makes sense. It’s practical, economical and simple to drive. It’s rational, just like digital. But, really, I would enjoy short trips like that much more if I’d do them in a 1970’s Fiat 500. Make an ordinary, daily, routine activity that bit more special, personal, intimate and meaningful, simply by making it slower.

Poetic almost.

Even with all that in mind I’ve met plenty of people who disagree. What’s so special about chemistry and darkroom? But that is where an open mind helps. My father grew up with film. In his days, film was in constant pursuit of quality. Slow, fiddly, messy analog photography was the daily thing, and it is only natural he found digital to be so much better. After all, it really is that much easier, and the result is often just as good, and in some cases, for some people – better. Me – I grew up with the sterile, perfect quality of digital, with speed and flexibility it had to offer. And, for personal projects and family photos for an actual album made of actual paper, I grew tired of it. I grew tired of the sheer amount of photographs, the constant clicking, the constant work with a computer. I leave that for my business. Don’t get me wrong, I use my Nikon D700 very often, but that’s the main course. Dessert is the goal. While a step forward for my dad was embracing digital and going fast, a step forward for me is embracing film and slowing down. Embracing quality of aesthetics rather than the quality of pixels.

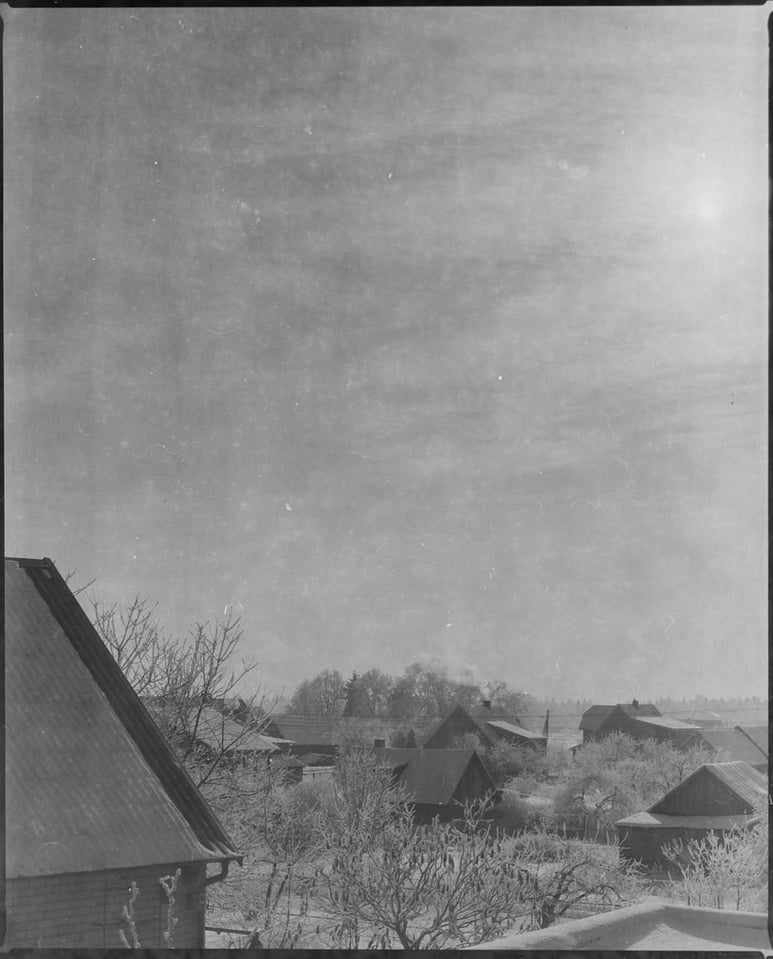

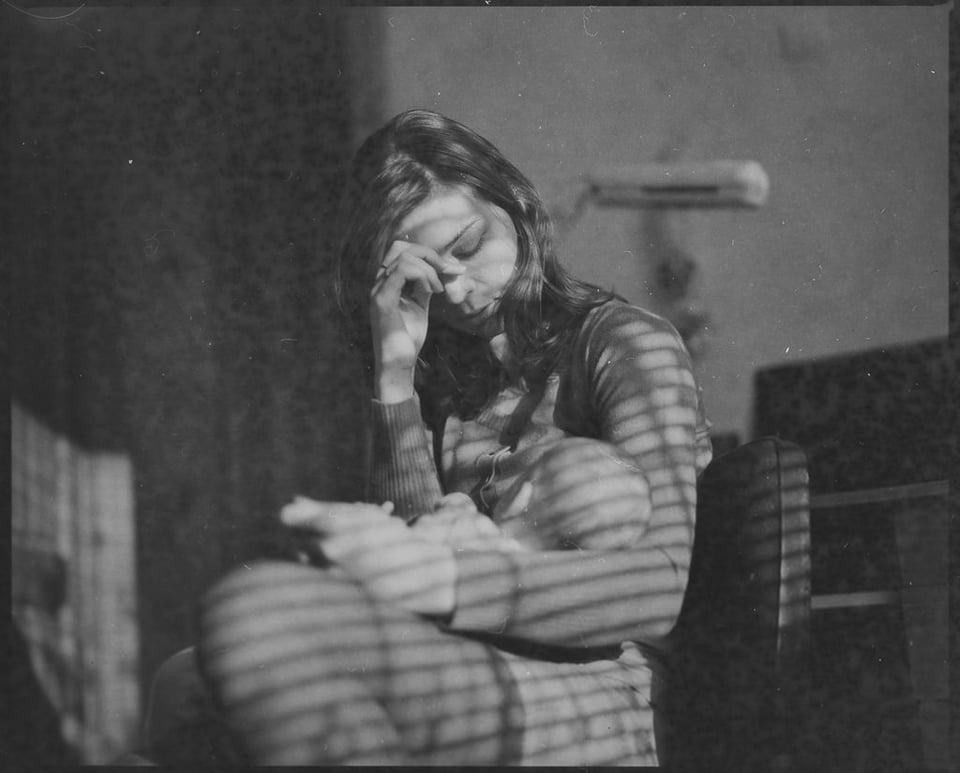

A side note: I use other film cameras and formats, too. The two above sample images were captured using my Kiev 4AM 35mm rangefinder camera, which is a copy of an old Contax. All the sample images here (except of the Mamiya camera itself) are scans or negative macro shots and are only good for previewing purposes. There will be no sharpness comparisons, no high ISO tests with film, no dynamic range graphs. Because it’s a film camera. It is in almost every measurable way worse than my D700, and yet I love it so much more. This is a camera for the photography artist within you, not a tech-expert. This camera is among the purest photographic equipment and, at the same time, it’s something that can’t be seen as a simple tool. More like a friend, actually. With a certain character. It either bonds with you or doesn’t. You either see through it deeper than with your own eyes, or not. In the latter case, you may need something else.

The Technical Review

Film Used

I’ve been using this camera for over a year now, but it is not quite the same kind of use your brand new Fujifilm X-Pro1 would receive during just the first few days. Simply put, I’ve made somewhat over 100 photographs with it, which equals 12 or so film rolls (10 shots each). Three of these rolls I’ve already developed myself – rolls of film that are about 20 years past their expiration date and were kept in room temperatures (about 20 degrees Celsius), it’s an old soviet black & white Svema 125. Naturally, two decades in decently warm temperatures had to have an effect, and as I expected, film was heavily covered in mold. I found that to be an interesting graphical touch to my “test” images – a sort of natural, mood-setting texture, and I’m sad to say I’ve now run out of Svema rolls.

I’ve been using this camera for over a year now, but it is not quite the same kind of use your brand new Fujifilm X-Pro1 would receive during just the first few days. Simply put, I’ve made somewhat over 100 photographs with it, which equals 12 or so film rolls (10 shots each). Three of these rolls I’ve already developed myself – rolls of film that are about 20 years past their expiration date and were kept in room temperatures (about 20 degrees Celsius), it’s an old soviet black & white Svema 125. Naturally, two decades in decently warm temperatures had to have an effect, and as I expected, film was heavily covered in mold. I found that to be an interesting graphical touch to my “test” images – a sort of natural, mood-setting texture, and I’m sad to say I’ve now run out of Svema rolls.

Developing Svema rolls was a tricky feat. With time, the old film tends to lose sensitivity to light (ISO), and by a different degree depending on type/brand/storing conditions (storing them in a fridge helps minimize the effect, but never completely saves you from it). I had to guesstimate how sensitive my rolls of Svema 125 were after 20 years. I chose to expose them as if they were ISO 50, and then added about a minute to develop time in a darkroom. My guess was accurate enough – I ended up with usable images rather than nothing (a little underexposed, but that may have been in part due to my light metering skills), and was glad my experiment turned out to be quite successful.

The other rolls I used for testing were of current, cheap-ish Shanghai GP3 film. I gave them up to a professional service for development and then scanned preview samples using Epson V700 scanner.

About This Camera – RB67, RZ67 II, Lenses, Accessories, “Sensor” Size

Mamiya RZ67 Pro is a successor to the fully manual, very heavy and tough Mamiya RB67. These two cameras use a very similar mount and certain RB67 lenses can be used on a Mamiya RZ67 Pro. Several RB67-specific accessories can also be used on the newer, electronic body, such as film backs. However, both these accessories and lenses will have limitations due to RB67 being completely mechanical (RZ67 uses an electronically controlled shutter and several other components). RB67 cannot be mounted with the newer RZ67 lenses due to different flange distance (lens mount to film plane distance).

The camera I have is a predecessor to the RZ67 Pro II and RZ67 Pro IID cameras. All three are very similar and use bellows for focusing. The later cameras have half-stop shutter speeds (my camera only has full-stop shutter settings). The latest Pro IID camera has an electronic coupling which allows simple use of modern digital backs. This camera is still sold new.

Mamiya RZ67 is a modular camera, which means it has many interchangeable parts, such as viewfinders (waist-level or AE-enabled prism) and focusing screens. Also, there are several different film backs with different frame size support (6×7, 6×6, 6×4.5).

Mamiya RZ67 is a modular camera, which means it has many interchangeable parts, such as viewfinders (waist-level or AE-enabled prism) and focusing screens. Also, there are several different film backs with different frame size support (6×7, 6×6, 6×4.5).

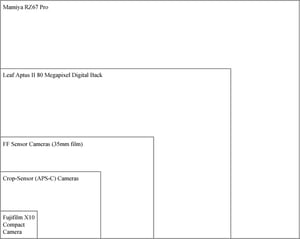

If you take a look at the image, you will see a comparison between different modern sensor sizes and the size of 6×7 film frame of my Mamiya RZ67 Pro. Do note that the comparison is not of real-world scale. The size difference between a 6×7 and 36x24mm frame used in modern FF DSLRs is quite striking. You can fit four FF sensors into that huge frame with ease!

In case you want to find out more technical details about this camera, there is no better place to look for that kind of information than at Camerapedia.

Build Quality

It’s plastic and tough, but I wouldn’t want to drop it. The old RB67 had a metal body and if I ever dropped that, I’d be worried I’d crack the floor just like my Nikon D700 probably would. With the newer camera, however, I’d be worried that both the floor and RZ67 itself would fall apart on impact.

It’s plastic and tough, but I wouldn’t want to drop it. The old RB67 had a metal body and if I ever dropped that, I’d be worried I’d crack the floor just like my Nikon D700 probably would. With the newer camera, however, I’d be worried that both the floor and RZ67 itself would fall apart on impact.

This Mamiya camera has a huge mirror, which is easier to break than smaller ones. Bellows are also very vulnerable. However, nothing ever feels flimsy and the camera seems to shrug off any light abuse I throw at it with reasonable ease. Despite that, I try to be as careful with it as I can. Everything is tight, secure and makes me feel as if it will last longer than I with proper care.

Handling, Ergonomics and Features

This camera is positively enormous. It is much bigger than my D700, which feels like a point-and-shoot next to it. Such size is partly due to the camera’s unique feature – revolving back, which can be rotated independently from the body itself into either portrait or landscape orientation. In order to do that you need to move the switch on the side of the camera to “R” position, rotate the back and return the switch back again to the middle position. “M” position of the switch stands for “Multiple exposure” and allows you to cock up shutter and mirror mechanisms without winding the film. By doing so you can expose a single frame as many times as you like.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro is also much heavier than the Nikon D700, weighing about two-and-a-half kilograms with the 110mm f/2.8 Sekor lens mounted. Such immense size and weight mean it is not as easy to handle as your conventional DSLR. Understandable, because Mamiya RZ67 Pro was always meant to be used as a studio camera mounted on a tripod. Speaking of tripods, by the way – you will need a sturdy one. When mounted, it is very well-balanced due to the great weight distribution of that box-shaped body.

If you decide not to use a tripod and shoot on-location, you will only be able to hand-hold the camera for longer periods in both hands. This is because of the weight, shape, and size. Thankfully, bellows are very easy to focus with and allow you to hold the camera with both hands at all times. Moreover, bellow focusing allows you to focus your lenses very close, which nearly turns my normal 110mm f/2.8 Sekor lens into a macro lens.

Other than that using the camera is very simple. There are no menus to play with. You set the aperture on the lens, which also has a leaf shutter in it supporting full-stop speeds of up to 1/400th of a second. Shutter speed is set on the body using a dedicated dial. You may use the top shutter speed without batteries. “A” stands for Aperture priority exposure and works with AE-enabled pentaprism viewfinder. You may focus by turning a focusing knob on either side of the camera. As you focus closer, the bellows extend. If you focus very closely, the effective aperture gets smaller (physics). There is a special diagram on the side of the camera which lets you know if you should adjust your exposure depending on current focus distance.

Film wind lever does the job in a single stroke and offers good resistance. There is a safety lock that stops you from winding further on in case you haven’t exposed the current frame yet.

Pulling two separate levers on the side of the film back will allow you to open it to change film. You can remove the back completely by pulling special levers at the bottom of the back at the same time, which will decouple it from the camera. Insert a dark slide to remove the back without exposing any frames – this is great if you have several backs with different film in them. Film backs have ISO speed dials on them, which work well as reminders or when used with AE-enabled pentaprism viewfinders for accurate exposure.

The shutter release button is located at the front of the camera for easy access with your right hand. It can be rotated to a lock position (red dot) to prevent accidental exposure. Rotate to orange dot position to use mechanical 1/400th of a second shutter speed if you’ve run out of batteries (which may not happen for several months or even over a year). If you want to use the mirror lock-up feature, screw in a remote-control wire into the lens. Pressing the shutter release button on the camera now will raise the mirror (with a loud clunk). Press the remote release to expose your film with no vibration for critically sharp work. You could barely hear the whisper-quiet leaf shutter, too – it sets off with a brief tick.

That’s it!

Waist-Level Finder

The very minute I held this wonderful piece of photographic brilliance in my hands I just wanted to take a look at the world through that gigantic window. This is, by far, what I love the most about medium format cameras. Waist-level finder fitted to my Mamiya RZ67 Pro body is simply magnificent. It may sound a little freakish, but at times, I like to pick it up and stare at just about anything. The first thought I had when I took my first glance through the finder was – “why can’t it do video?!”. And I am being serious – it’s quite magical to behold for anyone who’s used to those tiny DSLR viewfinders. It’s completely different, and, dare I say, extremely 3D-like.

When you look through it, move around and focus, the first thing you notice is that left has become right, and right has become left (this is because there is no pentaprism to reverse that light again – it’s a mirror reflection). It makes framing while looking through the finder quite a bit more difficult than you might think – I still get confused at times. The second thing you notice is just how great everything looks. And I do mean everything. As if captured on a piece of video-enabled Polaroid sheet.

Focusing is very simple – the image just snaps into the sharp plane like nothing else I’ve ever seen. In case you want to double-check, there is also a magnifying glass available for critical focus. There is a small split-screen for even more focus aid. Once I got the hang of it, I just kept walking around and focusing at different things all day. It is very involving, that finder, and I recommend it to anyone who doesn’t need auto-exposure of any sort.

If I were to be picky, I’d say the finder gets quite dark as soon as light levels drop to anything bellow bright. That is because the screen is mate and not optimized for slow zoom lenses. On the upside, which for me is quite a bit more significant, you can see the accurate depth of field no matter what aperture you’re on.

All in all, a very important part of the package. Waist-level finder makes me want to photograph everything through it even with my digital cameras, that’s how childishly enthusiastic I am. It just looks so much better.

The Lens

While there are several lenses available for RZ67, including tilt-shift and zoom, mine comes fitted with a normal prime lens. It has a focal length of 110mm and an aperture of f/2.8. Now, you may find yourself somewhat bewildered by the words “normal” and “focal length of 110mm”, but don’t forget what camera we are dealing with. The frame of this medium format Mamiya SLR is roughly four times bigger than that of a 35mm sensor/film. In other words – if one would want to calculate the equivalent focal length of a given lens, they’d have to consider the 2x-ish crop factor. Thus a 110mm lens mounted on a Mamiya RZ67 behaves very closely to a classic 50mm lens on a FF camera body. It’s noticeably not as wide because of the different frame format, which is closer to 4:3 rather than 3:2.

The lens is also similar to 50mm f/1.4 lenses in terms of relative fastness within the system and depth of field. Yes, it may be “only” f/2.8, but that effectively makes this Sekor lens the fastest in Mamiya RZ lineup. When used with this camera, it provides a very narrow depth of field, similar to a 50mm f/1.4 lens on your great 5D III or D800. The only difference is, while providing amazing aesthetics, f/2.8 doesn’t gather as much light. But then, it’s film. I’m not in a hurry and surely not shooting sports with it.

Mamiya 110mm f/2.8 Sekor is built very well, packs a 77mm filter thread and is quite heavy. You will also find a separate remote control thread, which is used when in mirror lock-up mode (leaf shutter is built into the lens). I wasn’t paying much attention to it, but it seems to be extremely sharp, too. When shot optimally, this kit, coupled with a high-resolution film, would easily triumph over Nikon D800 in terms of detail. But that’s not at all what I’m interested in. Let’s get back to aesthetics!

The Fun Review

None of the above matters. Focusing, accessories, history, lenses, and viewfinder are completely irrelevant. Nothing else matters in the world if it doesn’t feel right. And oh boy it does.

The first thing I find refreshing when it comes to using the camera is, strangely, the aspect ratio of 6×7 film. I’ve always found 3:2 sensors and film to be great for the majority of horizontal shots, but more often than not too narrow for vertical pictures. For this reason, I would often hesitate to change my framing in fear I’d lose too much horizontal context. This aspect ration, however, works perfectly for me. When framed horizontally, it almost looks square, which I find a very pleasing framing. When used vertically, it’s just narrow enough to notice and give a pleasing portrait, but also wide enough at the sides not to lose too much of the environment. I find I can use this aspect ratio for vertical landscapes far more often than the wider 3:2 aspect ratio.

Old, manual cameras impose a different style of shooting. You slow down. You pay more attention to composition, details within the frame, rather than an AF point or WB setting. It imposes you to concentrate more on what you are seeing. It helps you dive into that moment, breathless, surrounded by nothing but your feelings. It really does sometimes seem as if time just stops until I hear that loud clunk until I set off that shutter with a very definitive press on the release. And then it’s all back to normal again, the only difference being a strange, satisfied, subtle smile on my face. And the image? Well, it’s in my mind, of course. Clear and beautiful, somewhat dreamy as film can be. Like a memory, almost. And exactly how I saw it. I may not have even seen the photograph yet, but this Mamiya manages to put a smile on my face with every shot I take. Imagine if your professional 1DX or D4 could do that. You’d just shoot away at tens of frames per second and never seize to smile so wide your cheeks would hurt.

It is also a very interesting camera to shoot people with. Usually, whenever a digital camera is pointed at a person, they will change in some way. At times, it will be a very noticeable change – a person may suddenly stop doing whatever he or she was doing and turn away. They may stop smiling or, on the contrary, smile at you waiting for you to take that picture. At other times, the change is very subtle, but if you know anything about body language, it’s there and not always welcome – they may frown, or turn their bodies in a slightly different direction, away from you. They may become very self-conscious or even start to dislike you without realizing their feelings are clearly visible. It’s hard to say why exactly such a change occurs – it may be a psychological or a cultural thing. Whatever the reason is, it is extremely difficult to capture someone completely naturally as soon as they notice a digital camera. The moment’s usually gone. They are aware of being photographed and behave accordingly.

So what happens when I point RZ67 at them? Well, nothing, really. To them, to the people I’m interested in, this camera says nothing. It might as well be a book or a lump of bread. All they see is me looking down at some box and twisting knobs. To someone who’s not a photography enthusiast a medium format SLR, especially one with the waist-level finder, is just too peculiar to be seen as a camera. Subconsciously, they don’t seem to realize I could see them by looking down at a weird-shaped box, let alone photograph. Clunk – it’s done. That simple.

Fine, let’s put the unconventional looking Mamiya aside. What happens if I point my Kiev at someone? This is a little trickier and requires a bit more planning, a bit more quickness to it. Now, my subject is fully capable of realizing I am holding a camera and pointing it at them. But what kind of camera is it? Does it actually take pictures, or am I just asking myself the same kinds of questions while looking through that viewfinder? And so they get curious. Curious – not at all self-conscious. Kiev 4AM is small, light, much easier and somewhat quicker to handle. It also doesn’t make as much noise. Often, I can take that picture before they even notice or hear me. And when they do notice me first – it’s obviously a film camera. It doesn’t bite. It’s fine. So there, another shot – done. That simple.

If film is so great, so perfect in its imperfection, why did we all go digital you may ask? But it’s not the film, really. It’s the nostalgia, it’s the involvement, sentiments. These feelings and associations come with functionality. Old film cameras are much more direct, much more involving, similarly to how a car with a petrol engine is more fun to drive than an electric car. It’s about turning a dial rather than pressing a button. It’s about seeing your photograph appear on a piece of paper rather than saving a JPEG image on your laptop.

It’s about driving that focus gear, following that thin field of sharp focus until it lands where you want it to instead just autofocusing through an AF-dot obstructed viewfinder. Seeing how your image changes, grows, becomes your vision. You really do add more of yourself into your photography this way simply by doing everything that’s needed to take a picture yourself. Because of that, you start to see more, differently. And it’s not the same as focusing a 5D III manually. By doing that you would virtually try to turn your camera into a different one. It’s fake.

And not just functionality. Looks, too. Old film cameras are curious, inconspicuous. This is partly why such classic-looking cameras as Fujifilm X-Pro1, X-E1 and Olympus OM-D E-M5 work so well for wedding and street photographers. They don’t look modern, dangerous. They don’t push people into being self-conscious, at least not as quickly.

I must say, things would be different if you’d point a Nikon F6 at someone. That is why I mean what I say – it’s not about film. It’s the whole package. An automated film camera takes away all the advantages, the satisfaction, and pleasure of doing it all by yourself, and then gives you modern looks to scare your subject. I see them as somewhat pointless.

Shooting with a film camera will not make you a better photographer, but it will make you photograph differently, in a new way. It will help you notice new things, those you previously never thought were interesting. Decades later, digital cameras might take this place and become the more involving process than whatever we use at that time. As I now prefer dials to buttons, I will then prefer buttons to touchscreens or voice commands. As long as there are enough feeling and pleasure in taking photographs as well as looking at them.

Summary

And so I’ve established that this camera is in almost every technical way worse than probably anything you currently own. It’s slow, very big and very heavy, it’s missing most of today’s standard photographic features, such as AF and AE. And yet I love it. This Mamiya RZ67 Pro camera is of the “less is more” kind. There are no menus, no settings to fiddle with. You just grab it and use it as a tool, as an extension of your vision. One that makes the process feel so much better for me, it’s actually a little crazy.

A happy camera, this. A tool for my soul. And since it’s a choice I’m making with my heart rather than my head, metaphorically, I’ll take the 70’s Fiat 500, thank you.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro

- Features

- Build Quality

- Handling

- Value

- Image Quality

- Size and Weight

Photography Life Overall Rating

Having assisted several photographers in the late 80-90s and been around a lot of photographers in general. The RZ was the medium format film camera of choice. Digital was still in it’s infancy and film was king. By photographers I talking RANKIN, Mert and Marcus, Sean Ellis , PEROU, Vincent Peters, Phil Poynter, Liz Collin. RANKIN was using the RZ handheld most if the time in studio and on location. Yes it’s a heavy camera but not impossible to be handheld. Vincent Peters still only uses the RZ even today. Your point about speed is very important film, polaroids can force you to slow down, think about the cost per frame. I myself own an RZ and although I haven’t used mine in years I believe it still competes with a lot of current SLR’s.

The basic reason for liking the 6 X 7 format is because it is close to the Golden Mean.

Fantastic review. I read it from beginning to the end – though i only shoot Dslrs. That huge viewfinder !

Nice review, this will be my next step from my trusty etrs 645 :)

Just one thing, the wlf really is in 3D because you look at it with both eyes instead of a prism finder where you use both eyes. This gives it this incredible look, but its the same with all wlf even on the tiny Nikon F3

Dear Romans,

When were you born?

I am little surprised that you have added a features section and rated it as 2.

This camera was made in the beginning of the 80s and stood in competition with the Pentax 6X7, the RB itself, the 500 CMs, the Fuji 6X8 ( which probably gave this model the toughest competition– et al. Wouldn’t it be better to address the people born after the 90s with that perspective in mind rather than saying , I love this for the sake of being able to use my brain better rather than all those cameras whistling and hooting ? Yes, it is heavy. So was the Sinar. Now lets compare the Linhof Technika to the Nikon Z7. Cheers!

Fine article, sir! My only disagreement is your 4-1/2 star rating for Image Quality. After reviewing thousands of images trying to decide on MF format, system, and digital alternatives, I couldn’t rate the RB/RZ systems any less than a solid 5 stars—especially over digital. I’m not sure if it is the design of the glass, or method of focusing, using a bellows to move the entire assembly, rather than a single floating element, but examining the Mamiya images against Fuji (digital or analog) reveal a sharpness and three-dimensionality unlike any other system I can imagine.

Again, thank you for a terrific & informative review!

Wonderful article!

I have been a photographer for 35 years and after many years of using digital gear, I went back to film a few years ago. I now shoot exclusively black & white film (with two M4s and one RZ67) and made that choice for a number of reasons: 1) aesthetics — b&w film has a distinct look that I absolutely love; 2) slowness — in this day & age of instant gratification where every gadget in your life has a microchip and we are all addicted to staring at screens from the minute we get up until we go back to bed, I find it absolutely refreshing to work with purely mechanical devices. I enjoy that I am UNable to instantly see the pictures that I took. When I look at them days, sometimes weeks later (after developing and scanning), I am emotionally removed far enough from the experience of taking the photos that I can more objectively judge the quality of the photos; 3) to me, shooting film with un-metered mechanical cameras, manual focus, developing and printing photos on my own is a more holistic approach to photography because I have full control over the entire range of the photographic experience and can change the outcome of my photos at many stages during the process of creating my art. In the end, all that matters is creating a unique form of art!

nice review

I own rz67 pro II and few other film cameras

even I started in analog age and now use DSLR s still thinking that film is better in just one aspect photography is about print and I know many photographers who stop at digital file and film still pushing you to make print couse scanning negative dont get even close to wonder captured on that pice of foil called negative

Romanas,

Very well written article and I enjoyed reading it tremendously. Thank you very much. Aside from the information about camera itself, I can feel your passion and your love to the film, the camera, and off cause your life. I started with film cameras 40 some years ago in photography, and followed every step of the way that digital camera has been progressing. Now I am in search of a film camera system that will fulfill my dream of reaching magnificence in landscaping and portrait where DSLRs still are too far away from it. Mamiya RB67 or RZ67 looks very promising.

-Jin

Romanas,

Your Images are a `Breath from the Soul of Film`.

Your wife & child ~ wonderful .

Sunlight ~ through the trees . . .

You portrayed your thoughts ~ well.

Thank you,

~ Michael ~