One camera brand that has successfully fostered an aura of uniqueness, exclusivity, and luxury is the Leica. This German brand was there at the very beginning of 35mm cameras around a hundred years ago, and it still produces them today. Leica certainly doesn’t follow modern design trends; its strength lies in tradition. Decades-old models look very similar to current ones. And some do more than just look similar – the camera in today’s mini review, the Leica M Monochrom (Type 246), exclusively shoots black and white photos.

Table of Contents

Leica M Introduction

The history of Leica 35mm cameras dates back to 1913, when Oscar Barnack designed the first prototype. It was the first camera in which the iconic perforated film strip could be inserted. This was the beginning of the 24×36mm format still in use today.

One World War and ten years later, Oscar Barnack convinced Ernst Leitz that the 24×36mm format has a future, and the first 31 pre-production samples were made for testing. (Yes, these are the ones that show up at auctions from time to time and change hands for astronomical sums.)

To describe Leitz’ success with the new cameras would be like taking wood into the forest. Simply put, Leitz and his relatively compact cameras were a huge success that continues to this day. An integral part of the brand’s success, of course, are the many famous photographers associated with Leica cameras – Henri-Cartier Bresson, Robert Capa, and Sebastião Salgado, to name a few.

The 24×36mm format remains, but celluloid has (mostly) been replaced by silicon. Today, Leica interchangeable lens cameras come in two forms. One is more in line with current trends – the Leica SL series – and one stays true to its roots – the M series.

As I mentioned earlier, the basic concept of the Leica M has remained the same for decades. If you put a 1954 Leica M3 and a current digital Leica M side by side on a table, you’ll notice that their appearance hasn’t changed much. Of course, the film rewind lever and the film counter have disappeared, and an LCD covers the back, but the designs remain close cousins. On the Leica M Monochrom that I tested, you even still need to remove the entire bottom plate to get to the battery and memory card!

What else distinguishes the Leica M cameras? On one hand, it’s durability, reliability, and build quality. But most of all, it’s the very specific handling. When I got my hands on a Leica M Monochrom for the first time, I was reminded of my first experiences with a camera – a Minolta Hi-Matic F with a rangefinder that my family had when I was a kid.

If you’ve never photographed with a rangefinder camera, here’s a brief description of what it’s all about. With DSLRs and mirrorless cameras, you look at the world through the lens (either optically with a DSLR or digitally with an electronic viewfinder). With rangefinder cameras, the viewfinder is a small window at the edge of the camera, and it doesn’t look directly through the lens.

Instead, on a rangefinder, there are marked boundaries for different focal lengths (the M Monochrom automatically adjusts them to the lens you’re using). These give you an idea of the field of view. To focus, there is a small rectangle in the center of the viewfinder. There, you can see the doubled contours of the objects – when the contours merge, you’ve focused properly.

What are the benefits of this system? By having the viewfinder at the edge of the camera, you can easily keep both eyes open while taking photos. The viewfinder also allows you to see beyond the edges of your composition, so you can anticipate things better. In addition, with practice, it is easier to manually focus with a rangefinder than most people ever expect.

A certain disadvantage of the rangefinder concept is that the viewfinder cannot cover extreme focal lengths. Actually, it doesn’t need to, because the range of native lenses for the Leica M isn’t that wide. It starts at 16 mm and goes up to 135 mm. Still, for anything wider than 28mm, you’ll either need an external Leica Visoflex viewfinder, or you’ll have to focus via Live View and Focus Peaking. However, if you’re a classic Leica shooter, you’ll probably have a 28mm, 35mm or 50mm lens mounted anyway.

Also, keep in mind that you usually can’t focus very close with Leica M lenses. In fact, the lens I had, the Leica Summicron-M 35mm f/2 ASPH, lets you get within 70cm (27.5 inches), not an inch closer. So, these cameras are not made for macro photographers. Also, sports and wildlife photographers will probably reach for something else and save the family budget a fair amount of money.

By the way, if you’re thinking about how to justify the purchase of an expensive wildlife photography lens, like a 400mm f/2.8 or 600mm f/4, to your family, I have a tip for you. Just try explaining that you’re saving them thousands of dollars compared to the Leica M11 Monochrom and Noctilux-M 50mm f/0.95 lens! (Which totals $22,190.) Everyone has to admit that’s a better deal, right? Please don’t send me a bill for a lawyer if this doesn’t work out.

So, in whose hands does the Leica M belong? Going back to the photographers who I mentioned above, I think it’s clear. The Leica M is a tool for reportage, documentary, and street photographers. These are the people who appreciate its ability to blend in with the crowd, and who love the normal focal lengths.

Leica Monochrom – The World in Shades of Gray

When the first digital Leica Monochrom was released in 2012, many people scratched their heads. A black-and-white camera for eight grand? Only a fool would buy such a thing. But it seems that the world is full of fools who don’t hesitate to pay such a sum. The proof of this is that in April 2023, Leica introduced the fourth generation of this camera, the Leica M11 Monochrom. (The one I tested today is the second generation, released in 2015 as the successor to the first Monochrom.)

You may have wondered, as I have, why someone would voluntarily give up color photography these days. After all, there’s nothing easier than converting a color image to grayscale. You don’t have to be a Photoshop expert. There are plug-ins (such as DxO Silver Efex) that even let you choose from many simulations of classic black-and-white films. So, again, what is the point?

I would divide the reasons for buying a monochrome camera into two piles: ideological and technical reasons. I’ll start with the former, and if I’ve missed anything or simply misunderstood something, feel free to let me know in the comments below the article.

First, something unique happens when you don’t even have the possibility of getting a color photo with the tool in your hands. With most cameras, even if you plan to shoot in black and white, you still have a kind of “color backup” in your head. You’re constantly straddling two worlds – the world of color and the world of shades of grey. It’s like watching a movie with subtitles. Even when you understand the language spoken in the movie, you still find yourself reading the subtitles. Just in case.

A monochrome camera frees you from this addiction to color. It just doesn’t give you the chance to do otherwise; it forces you to think in black and white. In an Orwellian way, sometimes constraints lead to freedom. A black and white sensor takes away the colors, and in doing so, it teaches – even forces – you to perceive contrast, rhythm, texture, and deeper meaning.

What about the technical reasons? Are photographs taken with a monochrome camera better? Theoretically, yes. There are some benefits to using a monochrome sensor rather than converting a color image to black and white. Let me explain that next.

Technical Benefits of a Monochrome Sensor

Let us take a small detour into how camera sensors generate color in the first place. Namely, even a color camera sensor (at least with most designs) is actually a monochrome sensor. Each pixel has a red, green, or blue micro-filter on top of it. These only allow their particular color to pass through. The camera then interpolates the missing data at each pixel based upon how its neighbors have observed the world. This process is what allows color photography to be possible with today’s sensors. However, at a pixel level, it also reduces detail, captures less light, and allows for the possibility of certain unwanted artifacts (like moire) more than with a monochrome sensor.

By removing the color filters, a monochrome sensor can be much simpler. A monochrome sensor has no Bayer filter or low-pass filter. All that is recorded by the individual pixels are the luminance levels. Each individual pixel thus participates in the reproduction of the image. There is no need to interpolate pixels, and there are no filters to cut out the light you’ll capture. The resulting image should be significantly sharper (at least with proper focus and a good lens). In low light, it also will have less noise.

Leica Monochrom in My Hands

Before you read any further, please bear in mind that I had a second-generation Leica Monochrom at my disposal. That is, a camera manufactured in 2015. The current model is more advanced, but this one answers the questions that I had – whether a dedicated black and white camera is something I will fall in love with, or if it will strike me as little more than a gimmick.

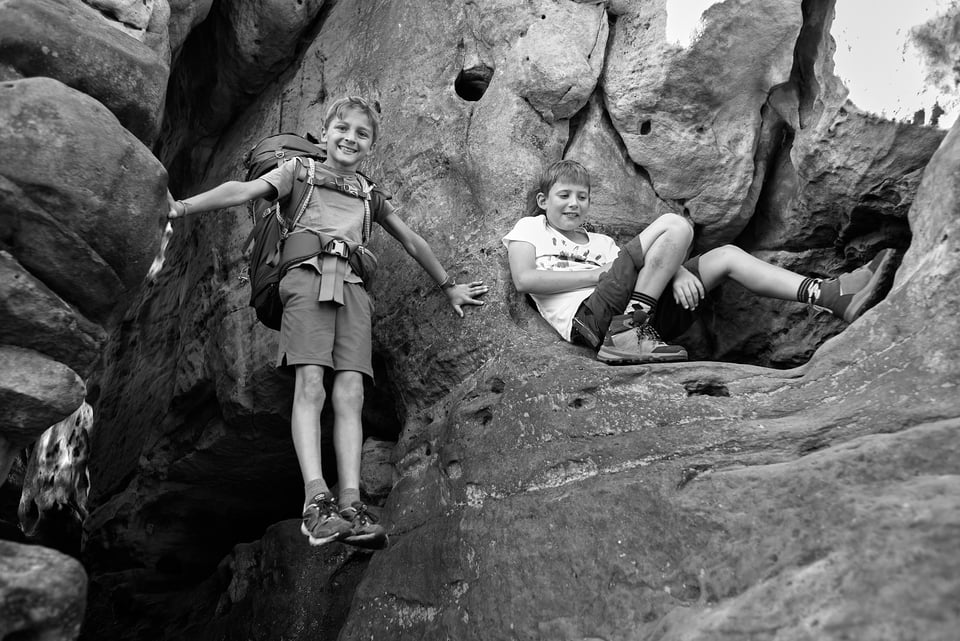

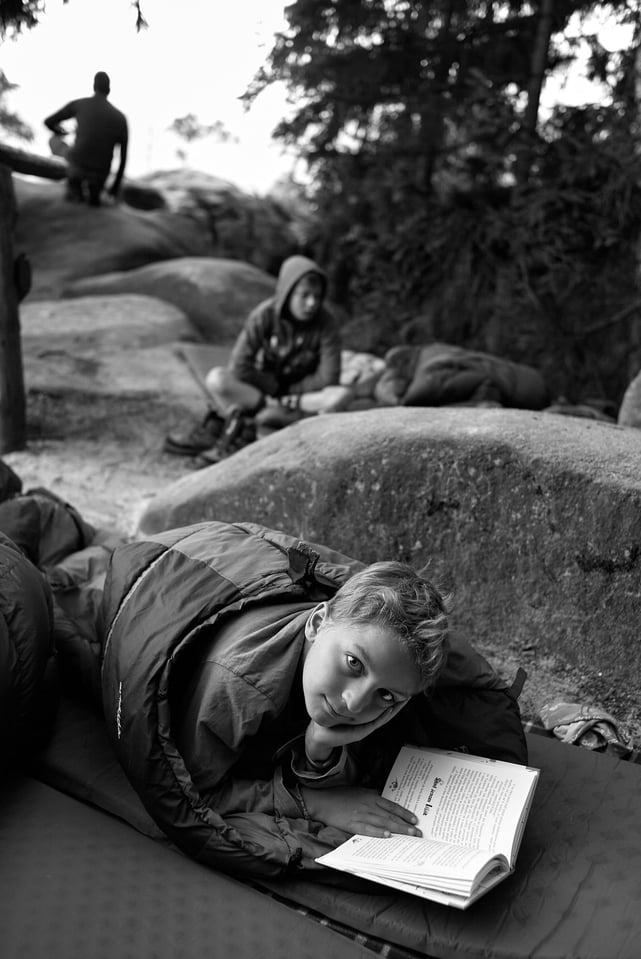

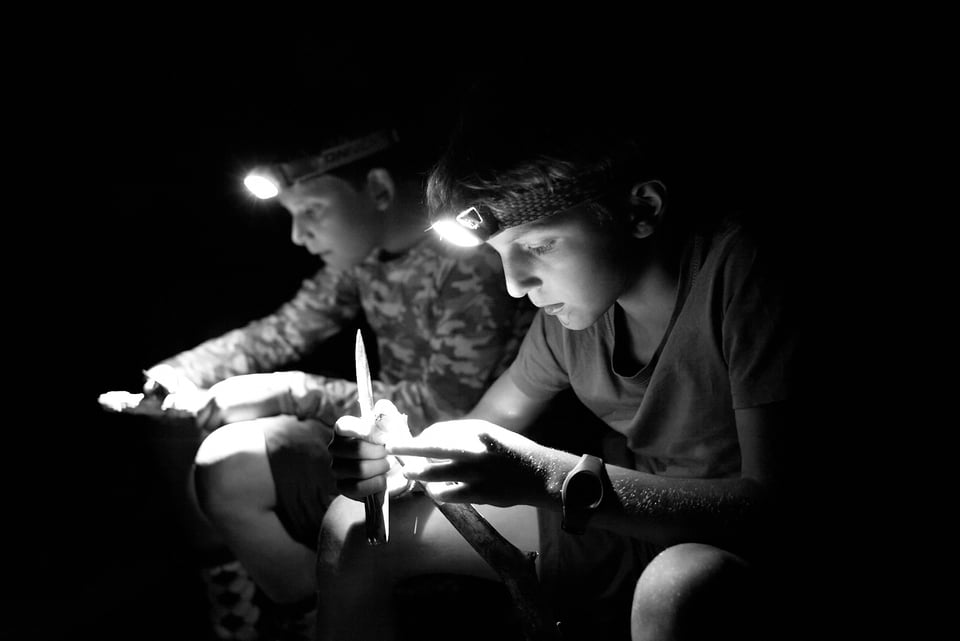

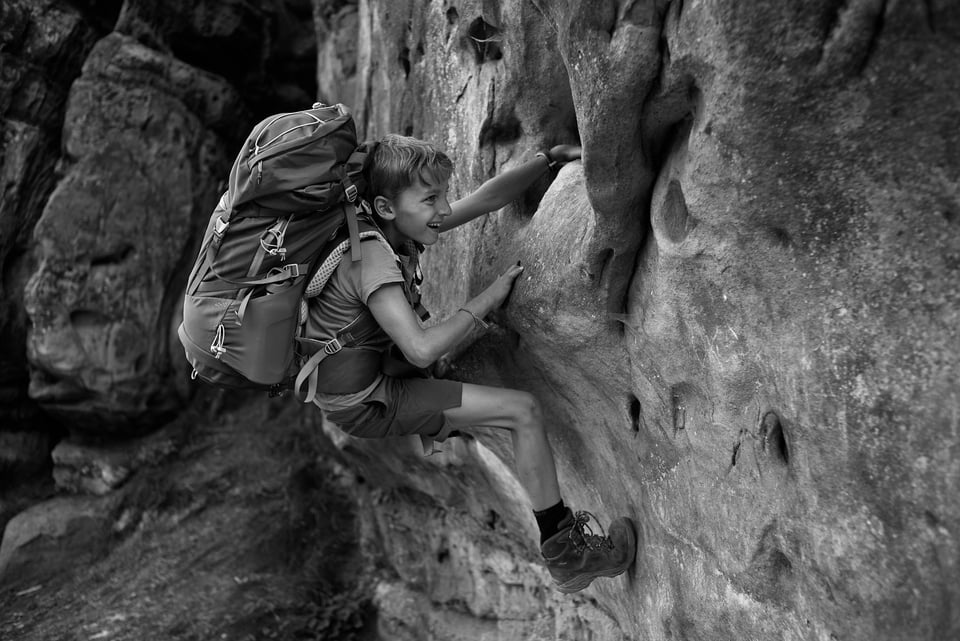

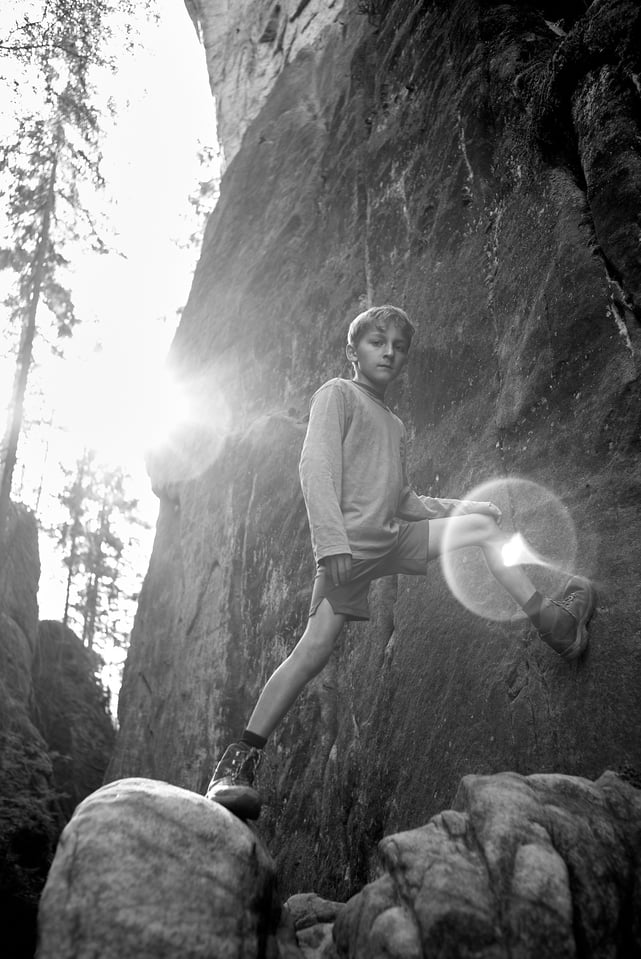

In an effort to escape my Nikon comfort zone, I packed up the Leica Monochrom as my only camera and went on a weekend camping trip with my friend. Two fathers, two sons, one Leica.

After the first few shots, I discovered that although the Leica has semi-automatic modes, I had to turn them off and switch to full manual control. My favorite mode – manual with Auto ISO – didn’t work the way I was used to. In particular, a strong light source in the frame would fool the metering system and leave me with a very underexposed image. So, I ended up shooting like a big boy, in full manual mode. That’s exactly what the Leica M wants you to do, anyway.

It’s important to note that nothing in the viewfinder tells you that you’re completely off. No preview of what the scene will look like, no histogram, no indication of overexposure. All you see in the viewfinder is a line-shaped area that represents the field of view of the lens (35mm in my case). Nonetheless, it didn’t take long before I was estimating my exposures pretty seamlessly, and did not need to chimp at the LCD for every shot.

What about focusing? A Leica in the hands of a master focuses as well as, and perhaps often better than, modern cameras with auto detection of everything. Once you get familiar with a particular lens and can estimate the distance, you can easily (after a few months of practice) focus before you even put the camera to your eye. Master street photographers, by the way, often shoot at waist level with a Leica in order to be even less obtrusive. Practice makes perfect.

I admit that I was a few months short of mastery, so I gratefully used the rangefinder in the viewfinder. And I have to say, it works really well. As soon as the two contours merge, you’re in focus. This method is very precise. And, to my pleasant surprise, it’s also usable in almost complete darkness.

That’s about it in terms of features worth talking about. Yes, the Leica can shoot video, but who cares? I already mentioned Live View, but honestly. Having a Leica and shooting with it like a cell phone? I would be a little embarrassed. Continuous shooting? 3 frames per second, if you care. Maximum ISO 25,000. That’s not bad. Minimum ISO 320! No, I didn’t make a mistake. If you’re going to put the Leica Monochrom in your shopping cart, throw in a neutral density filter – it’ll come in handy. Leica shoots these 24 megapixel files directly to DNG.

Although not all my software supported the Monochrom’s files (DxO PureRaw, for example), Capture One 23 was able to open the files. Normally, I’m spoiled in Capture One. Even extreme overexposure is usually fixable – at least, that’s been my experience when editing Nikon files. So, I imported the Leica Monochrom’s photos and started editing. To my surprise, I found that I could get almost nothing out of the highlights. So, don’t count on the Monochrom to be forgiving of bad technique.

In other words, the Leica M Monochrom is simply a purist’s camera from start to finish. From the spartan controls to the final image processing. But when it all comes together, the results are beautiful. When you look at the photos, do you see something like the distinctive Leica look? Something that makes pictures taken with a Leica – or specifically a Leica Monochrom – look unique? I have some ideas, but I don’t want to influence your opinion. I’d be very happy if you try to find an answer to these questions, or refute it altogether, in the comments below the article.

To sum up, I’m very glad that I got to try this camera, but don’t expect to buy a Leica M Monochrom for myself any time soon. The camera does give excellent black and white results, and using it was a fun experience. However, the limitations are severe enough that it has cured part of the Monochrom’s mystique to me. I think a street photographer would find it more tailored to their needs than I did.

I don’t know what is better: the camera or your photography, which is exceptionally beautiful and evocative. I see no need for color when looking at your photos and the Mono definitely has its own look.

Great pictures and you managed to focus correct as well! Very fine review, thanks.

I also have an M246 and when I mount the Summilux 50 ASPH and things fall into place, it’s just … well, magic. The sufficient sharpness, not overly sharp, the transition shadows/light is so smooth.

I agree with Per Erik, the Leica glow is owed to their lenses.

The new zf seem to have a black and white viewfinder. That might be better to avoid the colour issue. But no rangefinder unless you assume you can crop.

Leica never made a 1:1 like epson or Cosina rangefinder. Hence using both eye you may but it is not both eye open with the crop floating in the world.

Too much manipulation of filter on top of ND, need red to deal with no cloud issue etc?

Of course the photo come out great and memorable …

I forgot to mention that I’ve been able to shoot my type 240 using auto-ISO exactly as I do with my Nikon cameras.

Unlike Libor, I don’t use my Nikons in manual mode when shooting with auto-ISO. I use aperture priority because it’s easier to dial-in exposure compensation, which is frequently needed to create an accurate exposure in the situations I encounter.

By enabling “easy exposure compensation” — custom function B4 — I’m able to dial-in exposure compensation with the main control dial using my thumb without having to push the exposure compensation dial on the top of the camera body. The amount of exposure compensation is displayed on the analog scale in the camera’s finder.

Exposure compensation can be configured M240 in exactly the same way. The only difference is that the Leica doesn’t display the amount of exposure compensation on an analog scale — it displays the value with decimal numbers.

I’ve never used the type 246, but I suspect that its controls are similar to the 240.

Could the place of your trip actually be at Drábské světničky??

Hi Achmel, I see you are familiar with Czech morphology. You’re right that the Drábské světničky look quite similar. Actually, it’s the same kind of sandstone. But in this case I photographed a bit more to the north, in Broumovské Stěny and Adršpach Rocks.

The Leica Look or Leica Glow has to do with their lenses, and was known way back in their film cameras/lenses with Pleasing bokeh and good microcontrast as you can see in the pictures. Nikon also have some lenses like that, the 35mm f1.4G and 58mm f1.4G are examples. The sensor of the camera gives dense shadows and as you say, highlights thats burns out easy. Personally I like files with more «open» shadows and lighter skin tones than this Leica give. But transitions and rendering between/of the graytones are beautiful. Nice pictures…

Thank you, Per, for your comment. Personally, I see a certain Leica characteristic in the same thing you mention. The transition from highlights to shadows. The highlights are much more likely to fall outside the dynamic range of the sensor, but the transition is not distracting. And yes, the two Nikon lenses you mention have a very distinctive character. They’re certainly not sharpness champions, but they take beautiful photos.

Great article and beautiful pictures! Thanks for sharing 😊

Thank you for the nice comment, Pedro.

Thanks for sharing your experiences.

Leica does generally have good build quality but my recent experience with them seems to indicate that their quality isn’t what it used to be.

I started tinkering around with a few Leica M-series rangefinder film cameras and lenses about ten years ago. I eventually purchased a used M240 digital body in 2018.

With the exception of a 28mm Elmarit ASPH lens, everything I purchased was used, from reputable dealers. The 28mm lens was the only item that’s had issues. A couple of months after the passport warranty expired, the aperture ring broke and it cost about $450 to have Leica USA repair it. I’d barely used the lens, as most of my work since 2016 has been with wildlife.

You got some amazing shots here, Libor. Are you sure you’re not a portrait photographer?

Thanks a lot Jason. I just changed the species a little. The ligivistic connection between humans (or family members) and animals reminded me of my favorite childhood book. Maybe you’ve read My Family and Other Animals or Birds, Beasts and Relatives by Gerald Durrell.

Interesting discussion, and many outstanding photographs. Thanks.

Thank you for reading and for your comment, Quincy.