Distortion

Let’s start with distortion, the optical feature that Venus Optics advertises most of all for this lens. And, true to their claims, the Laowa 12mm f/2.8 has very little distortion. This is quite a feat for a 12mm lens. Here’s a sample image, which has about 1% barrel distortion (based on corrections needed in Photoshop). Our test chart measurements showed 1.11% distortion, although that decreases slightly as you focus farther and farther away. Not bad at all:

However, I have to point out that there are more important components of optics today than distortion. With film cameras, distortion was practically impossible to fix, and a zero-distortion 12mm lens would have been very highly sought after. But digitally, aside from slight composition changes and perhaps a bit of corner stretching, distortion is not that hard to correct in post-production. Personally, I would rather Venus Optics have improved other characteristics of the lens – which, as you’ll see below, are often sub-par – with a bit more distortion in exchange.

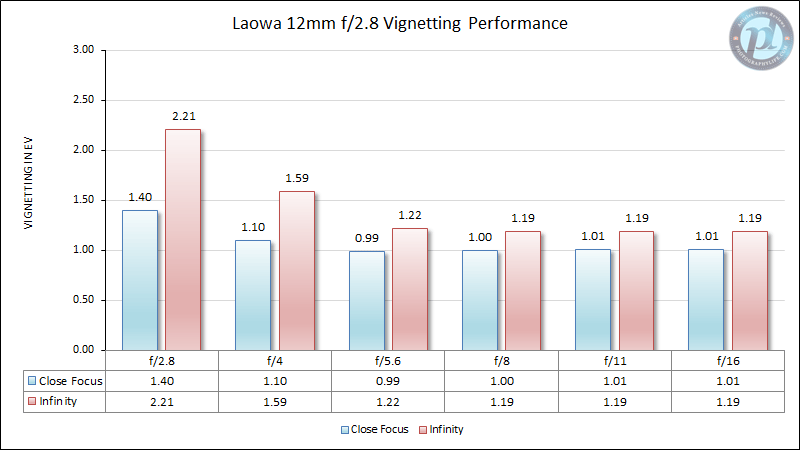

Vignetting

The Laowa 12mm f/2.8 has fairly high levels of vignetting wide open, more than two stops at infinity focus. This is enough to make photos at f/2.8 a headache to correct in post-processing, revealing additional noise in the corners as well. Here’s our vignetting graph:

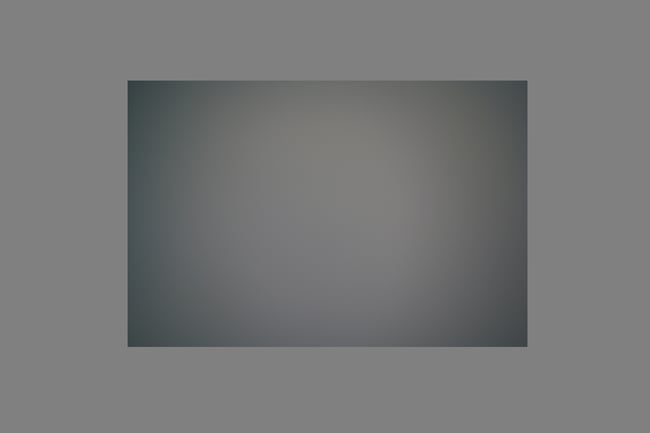

It’s not the worst performance in the world, but for a potential astrophotography lens, I would have hoped for better. On top of that, the 12mm f/2.8 also has blue color shifts in the corners – a moderate tint visible in certain images, and difficult to correct. It is easiest to see against a colorless background. In the case below, the center of the image has been corrected to neutral gray (same color as the background field). Taken at f/2.8 and closest focus:

However, it also turns up subtly in real-world photos from time to time. Here is one (uncorrected) example with some blue color shifts visible, especially clear at the bottom left. A perfect manual correction in cases like this can be pretty tricky:

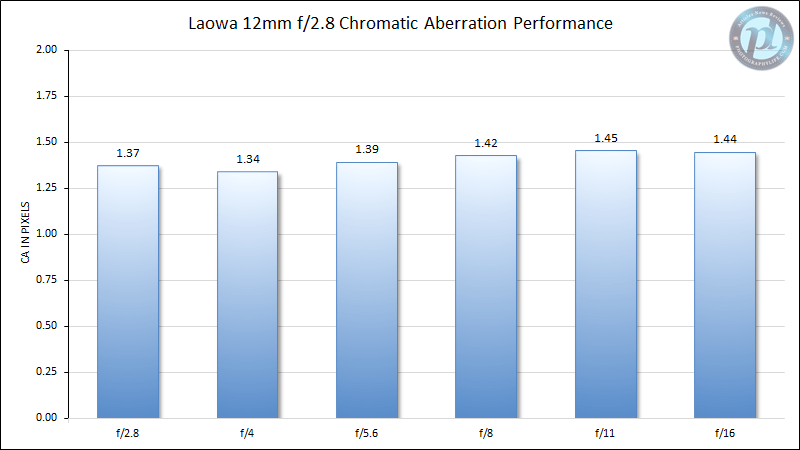

Chromatic Aberration

One area where the Laowa 12mm f/2.8 does fairly well is in chromatic aberration. It has only a moderate amount overall, not enough to worry about in most images. Chromatic aberration stays roughly the same across the aperture range, measuring around 1.4 pixels in each case. Here is our graph of lateral chromatic aberration on this lens:

By way of comparison, this is only slightly worse than the Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 at 14mm, and significantly better than the Nikon 24-70mm f/2.8 VR at 24mm. In real-world images, I can only see a bit of chromatic aberration in something like tree branches in the corner of an image.

For a 12mm lens, that is quite a good result. Even though chromatic aberration is usually removable in post-processing, excessive amounts cannot be fixed without leaving visible artifacts.

Flare

The Laowa 12mm f/2.8’s flare performance is interesting – not necessarily good or bad, but highly dependent on the placement of the sun in the frame. You can take photos where the flare is a giant, unsightly blob:

But then moving slightly will practically eliminate flare:

In some cases, when the sun is out of the frame, you will end up with significant levels of veiling flare:

But when the sun is in the photo, contrast almost always remains high, and veiling flare is hardly visible:

It almost looks like the photos above were taken with four different lenses! What’s to make of such varied behavior? Personally, my takeaway is that the Venus Optics 12mm f/2.8 is neither stellar nor horrible in terms of flare – even though, at times, it can be either. I don’t mind this type of performance; it means there is usually a composition in the field that minimizes flare better than most ultra-wide lenses.

To generalize, in a typical photo with the sun in it, you’ll see a streak of colorful flare – but not a big one, and not associated with contrast loss in the rest of the image. (The last image above is along the lines of what I’d see most often.) It’s generally correctable in post-processing without much issue. So, though not perfect, this is certainly acceptable performance to me.

Coma

If you were hoping for a new astrophotography lens, I don’t recommend this one. Even ignoring the vignetting, the Laowa 12mm f/2.8 has moderate levels of coma and poor corner sharpness wide open. No matter what you do, stars in the corner will look like they are a bit out of focus. When I tested five ultra-wide lenses side by side for astrophotography, the Laowa came in last in overall performance.

Here’s a sample photo, followed by a 100% crop from the top-right corner to show coma and softness:

That’s not to say it is impossible to take good Milky Way photos with this lens. It’s certainly the right focal length and aperture; you can get good nighttime shots with the Laowa, no doubt. However, unless you need 12mm for whatever reason, or you already own this lens for a different purpose, it would not be my top choice for Milky Way photography.

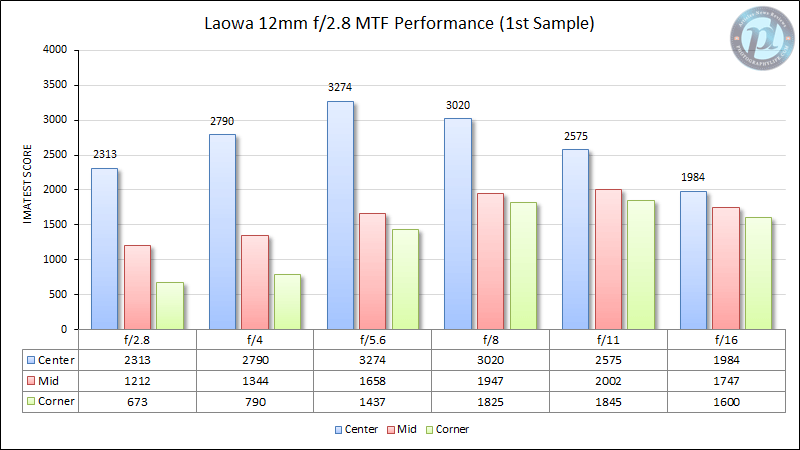

Sharpness

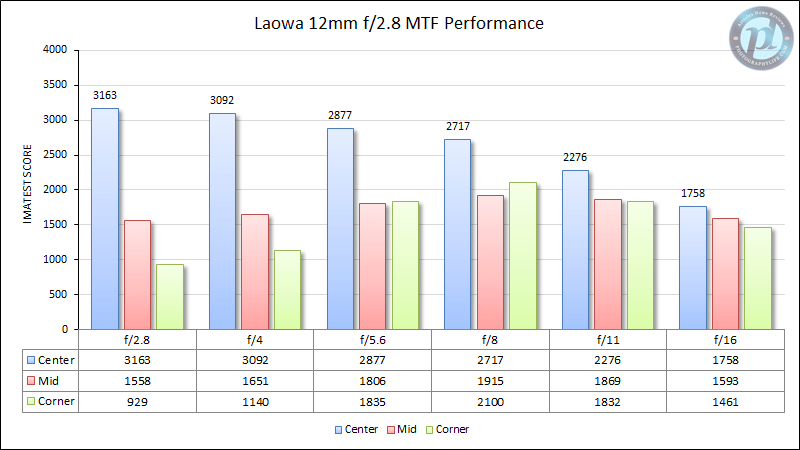

The Laowa 12mm f/2.8 is not the sharpest lens out there, although some of that is expected due to the extreme focal length. We tested two copies at Photography Life, and the sharpness numbers on both had some issues, especially in the corners, and especially at large apertures. Both copies were also significantly decentered, and we had to angle the camera significantly to get all four corners to be equal in sharpness for our test chart measurements. Here is the Imatest graph from our first sample, tested on a Nikon D810:

And then from the second sample, which was better in the corners (especially wide open), but still not great:

The good news is that center performance is solid across the aperture range. However, the corners have some definite issues, especially wide open. On our first copy, the corners were practically unusable until f/5.6. The second sample had better performance in this regard, with sharper corners throughout the aperture range. But as you’ll see on the comparisons page of this review, it still lags behind today’s popular 14mm lenses in overall performance.

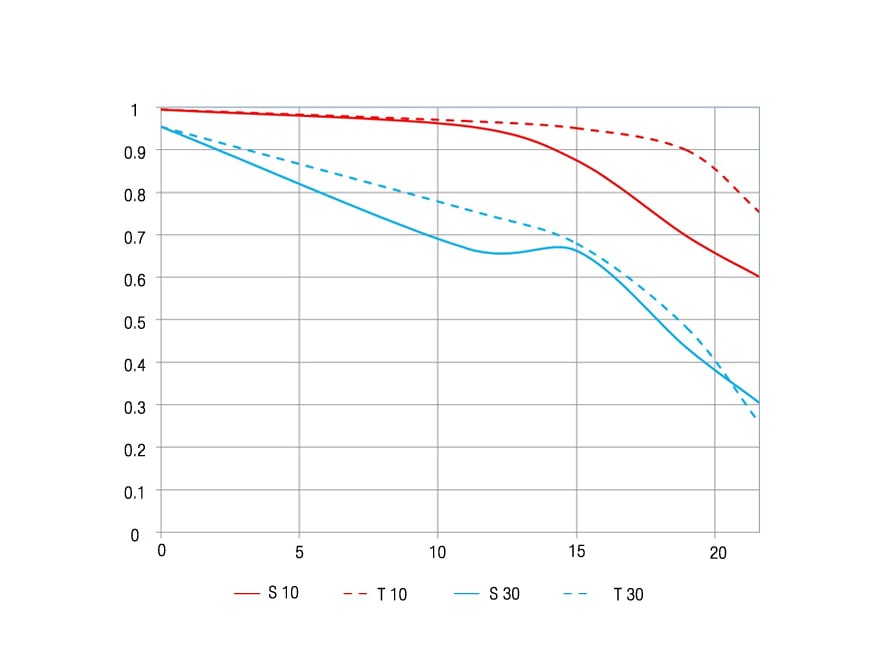

For comparison, here is the theoretical MTF chart provided by the manfacturer:

Is 12mm Too Wide?

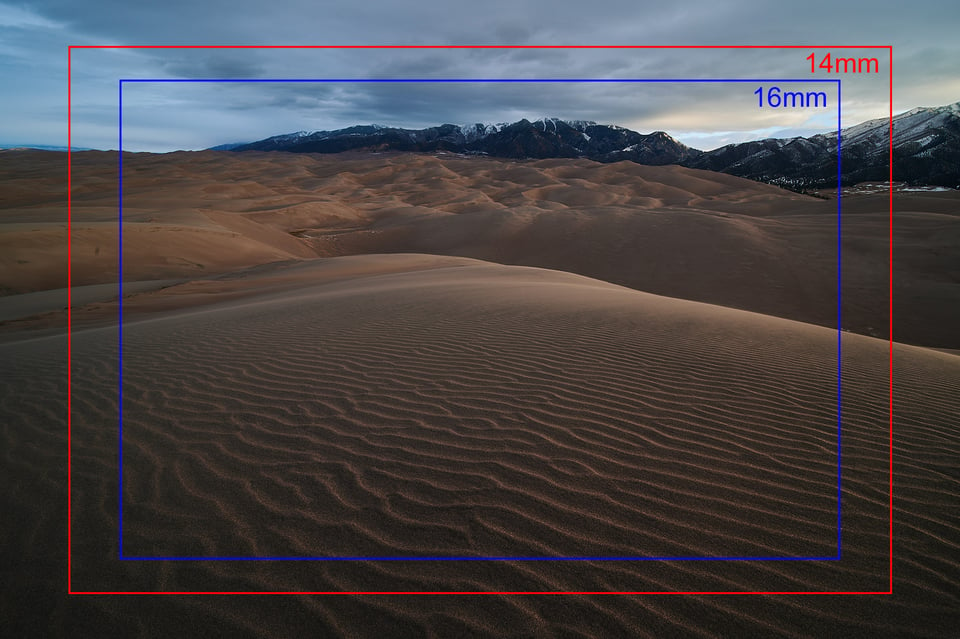

If you’ve never used an ultra-wide lens before – or even if the widest lens you own is in the 16-20mm range – 12mm will feel extreme. I’ve mentioned a couple times that most photographers don’t need something this wide, although I’ll grant that it can be difficult to know if you’re among them until you try it out yourself. If it clarifies things, here is a comparison of the relative crops of 12mm, 14mm, and 16mm:

12mm is so wide that you’ll often end up with unwanted elements in the photo, like your shadow or your tripod legs. No joke – it’s tricky to do vertical compositions from this lens without capturing part of your own tripod in the shot:

On top of that, when you’re at 12mm, you have to get so close to your subject that you introduce severe perspective distortion to your images. This is not something that Laowa’s “Zero-D” designation can fix, because it’s not a property of the lens but of physics. Essentially, objects near the lens will appear disproportional and exaggerated in size. That can lead to some really funky effects (for better or worse), like in the image below:

It takes a certain type of photographer to want a 12mm lens and all the special considerations surrounding one. This is not a casual walk-around lens, but a deliberate and purpose-built piece of equipment for images that you cannot capture with anything more normal. For some photographers, 12mm is absolutely useful and valuable to their work – and if that applies to you, the Laowa’s sharpness numbers probably won’t deter you.

But, all in all, I think that most photographers will be better off with a 14mm lens instead, whether prime or zoom. Many of those lenses are less expensive and higher in optical quality, not to mention that the 14mm focal length (as impractical as it, too, can be) is more reasonable for day-to-day photography.

Table of Contents