The Nikon 500mm f/5.6E PF VR is one of the most popular lenses for wildlife photography among Nikon photographers. It’s also my primary telephoto lens, and I’ve used it for more than four years of rigorous field work. Today, I’m reviewing the 500mm f/5.6 PF and sharing my full experience.

Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF Specifications

- Full Name: Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 500mm f/5.6E PF ED VR

- Focal Length: 500mm

- Aperture Range: f/5.6 to f/32

- Optical Design: 19 elements in 11 groups

- Diaphragm: 9 rounded blades

- Angle of View: 5° (Full frame)

- Minimum Focus Distance: 3m (9.8ft)

- Maximum Magnification: 0.18x (1:5.6)

- Length: 23.7cm (9.33″)

- Weight: 1.46kg (3.21lbs)

About the Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF

The Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF was announced in mid-2018, and I placed an order for it almost the moment of the announcement. What interested me about the 500mm f/5.6 was the compact size, light weight, and fast focusing speed. I like to be very mobile in my shooting style, often hiking long distances, so it seemed like a good fit for me from day one.

Nikon is known for the quality and variety of their supertelephoto lenses, but even in that context, the 500mm f/5.6 PF stands out. At 1.46kg (3.12lbs), the 500mm f/5.6 PF is one of the lightest 500mm lenses in existence. This is partly because of the narrow f/5.6 maximum aperture, and partly because of that acronym – PF.

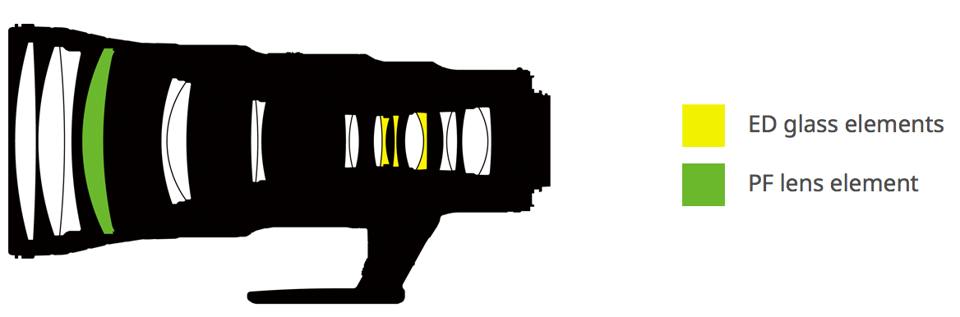

No, this lens wasn’t designed by a brilliant but mysterious optical engineer named Penelope Fisher (at least as far as I know). Rather, the acronym stands for Phase Fresnel. As you can see from the optical diagram of the 500mm f/5.6 PF, one of the lens elements near the front is a Phase Fresnel element:

If you’ve ever used an overhead projector, you’ve seen Fresnel lenses in action before. In these devices, a Fresnel element is used to provide light amplification with a flat, compact optical element – the flatness being required so that you could put a sheet of paper on it.

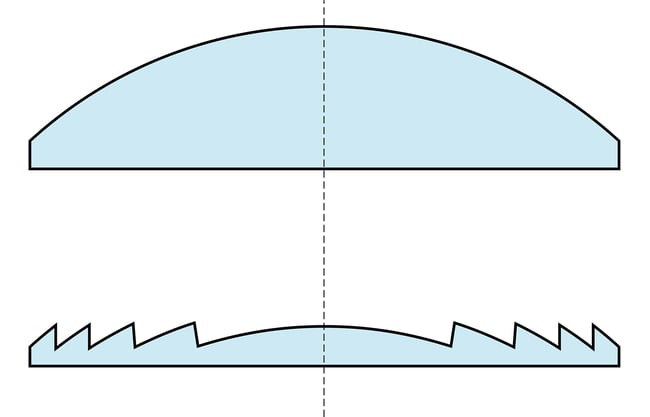

Fresnel elements are used in various other applications, from improving lighthouses to making “flat magnifying glasses” like this one. Unlike regular lens elements, they aren’t smooth on the surface. Instead, Fresnel elements have a series of ridges in a concentric circular pattern. It’s probably easier to show than to explain, so here’s an example cross-section of a regular lens element versus a Fresnel element:

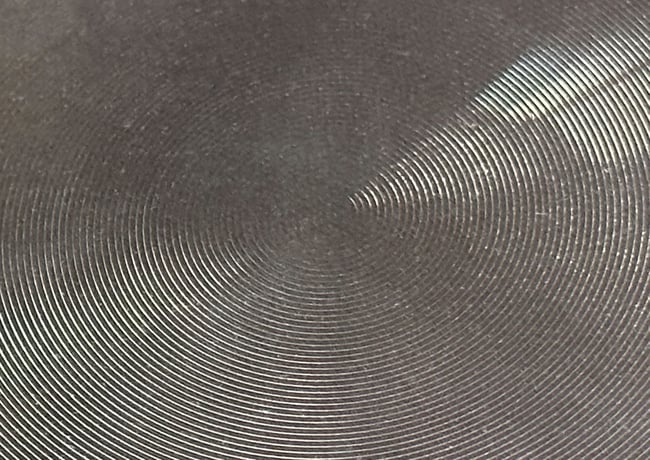

That’s how it would look in a cross-section. On the other hand, viewed from above, the Phase Fresnel lens element on the 500mm f/5.6 PF would look be a series of rings like this:

You can see from those two illustrations that Fresnel lens elements can be made much thinner than a traditional lens element, thus saving weight. Although Fresnel lenses are not without their downsides, they make a lot of sense for supertelephoto lenses, which are usually very large and heavy. Any size/weight savings is welcome.

The 500mm f/5.6 PF was the second Nikon lens to incorporate a Phase Fresnel element. The first was the Nikon 300mm f/4 PF lens, which is an absurdly small lens for a 300mm f/4. It’s also technology that Nikon is incorporating in the Z system – look no further than the Nikon Z 800mm f/6.3 PF VR S, for example.

Nikon probably took some inspiration from Canon, who has been producing lenses with Fresnel elements since 2001 and now has five of them (called “Diffractive Optical” elements in Canon’s terminology). Or, maybe Nikon just took some inspiration from lighthouses. Hard to say.

Usage in the Field

Compared to almost any other telephoto lenses on the market, what you’ll notice about the Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF is its light weight. That’s really the biggest reason to get this lens over something else. I’ve found that it’s easy to hike long distances with this lens without getting sore, and yet still get outstanding image quality.

What about the f/5.6 maximum aperture? It definitely makes the lens harder to use in low-light environments, especially in terms of autofocus. I have found that if I’m shooting even nonmoving subjects, and the light is low enough to require ISO 6400 or higher, the autofocus performance rapidly degrades. You’ll need to manually focus close to your target and wait for the AF system to hunt a bit. This is with DSLRs; you might get better performance when adapting this lens to a high-end mirrorless camera. Thankfully, most of my bird photography does not require shooting in such low light so I don’t worry about it too much.

As for teleconverters, Nikon’s 1.4X III teleconverter turns this lens into a workable 700mm f/8. Image quality is not really the problem – the bigger problem is that an f/8 lens is pushing the limit for most Nikon DSLRs. You’ll still get autofocus with the center AF point, and depending on the DSLR, maybe other autofocus points as well. With a mirrorless camera like the Nikon Z9, the results are going to be a bit better, with all the autofocus points still engaging. On the other hand, a 2x teleconverter is a bridge too far with this lens unless you’re doing a very specialized shot, like photographing the moon. A 1000mm f/11 just isn’t a very versatile lens.

I’ve seen a few people mention an issue with strange VR performance on this lens that occasionally causes slightly blurry images at certain shutter speeds. Rarely on the D500, I have noticed an odd jittery look, which may be due to shutter shock and the VR system, because I have never noticed this problem shooting the 500mm f/5.6 PF on the Nikon Z6 with the electronic shutter. But this problem appears sufficiently rarely that I have never lost a shot because of it, or been able to replicate it consistently. I still keep my VR on by default and recommend you do the same.

What about the 500mm focal length? It’s a great sweet spot for wildlife photography, although it can come up short for the smallest or most distant subjects if you’re shooting full-frame. On the Nikon D500, it’s just about perfect and even too long on occasion. Overall, I think that the 400-800mm range (full-frame equivalent) is the most versatile for wildlife photography, so I can’t complain.

Relevance in a Nikon Z Mirrorless World

If you’re shooting with a Nikon DSLR camera, the 500mm f/5.6 PF should be high on the list for almost anyone who needs a supertelephoto lens. But what about for Nikon’s mirrorless cameras? You’d need to use the 500mm f/5.6 PF with the FTZ adapter, which still works well, but a native lens would be preferable.

Nikon makes a few Z-series lenses that I think can be directly compared to the 500mm f/5.6 PF: The Nikon Z 400mm f/4.5, the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3, the Nikon Z 800mm f/6.3, and most of all the Nikon Z 600mm f/6.3 lens.

The 400mm f/4.5 is a great choice, too. It actually weighs a hair less than the 500mm f/5.6 PF and otherwise targets a very similar audience. Libor, my fellow writer at Photography Life, has used the Z 400mm f/4.5 lens and reports that it works very well with the 1.4X Z teleconverter, giving you a 560mm f/6.3 lens. Often, the Nikon 400mm f/4.5 can replace the 500mm f/5.6 PF lens for photographers who exclusively use the Nikon Z ecosystem, but it’s not completely ideal for birds due to its shorter focal length.

As for the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3, it’s a substantially heavier lens, but it’s less expensive and still lets you shoot at 500mm and (roughly) f/5.6. If you need the convenience of a zoom and don’t care so much about weight, it would be a good alternative.

The Nikon Z 800mm f/6.3 has a very similar field of view to the 500mm lens, if you’re using the 500mm on a DX camera and the 800mm lens on an FX camera. So, photographers like me who use the Nikon D500 + Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF combo may find the Z 800mm f/6.3 a more familiar fit on a full-frame camera like the Nikon Z9. It, too, is much heavier though – and also more expensive.

Finally, by far the closest lens in Z-mount to the 500mm f/5.6 is the Z 600mm f/6.3 lens, which we also reviewed. If you’re used to the 500mm f/5.6 PF, this newer 600mm lens will be right up your alley. The only downside compared to the 500mm lens is the 600mm f/6.3 is a bit more expensive (though expect used prices to be decent) and its slightly longer minimum focus distance of 4m versus 3m for the 500mm f/5.6 PF.

That said, if you already have the Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF, I don’t see a reason why you have to switch, even if you’ve moved to an all-mirrorless system. Optically and in terms of focus speed, you will gain surprisingly few benefits by switching to a native Z lens, considering how good the 500mm f/5.6 PF is (more on that later). On top of that, the 500mm f/5.6 PF lens make a great combination for a more budget-conscious photographer with the Z system, especially since many people are selling their 500mm f/5.6 PF lenses when they switch to mirrorless.

On the next page of this review, let’s take a look at the build quality and handling features of the Nikon 500mm f/5.6 PF.

Table of Contents