Despite all the recent photowalks shooting urban ephemera, my primary interest in photography was always wildlife and animal photography.

Forests of trees have been sacrificed to literature on this subject, and I accept with all humility that I may not have any earth-shattering technical insights to offer here. There have been plenty of excellent articles on this site alone about wildlife photography and the equipment one can use in its pursuit.

But elsewhere I have seen too many photos of wildlife and animals that have been captured simply because they were there. As laudable as they are, the most inspiring images for me are where the subject engaged me and caught my imagination, giving me a more profound relationship with it and enhancing my viewing experience.

Of course I am not an expert on the subject and would never claim to be. Nor will I wax lyrical about telephoto lenses and shutter speeds. This is an ideological submission in which I hope to reflect on a desire to capture something special, albeit sometimes typical, about wildlife.

This does not happen just by turning up, of course. All the usual advice applies. Learning about the animal and its behaviour; being in the right place at the right time; having a great deal of patience and reverence for the animal you wish to photograph, the last of those being most important. More than anything, however, since wildlife can be as unpredictable as we are, a tremendous amount of luck is involved too!

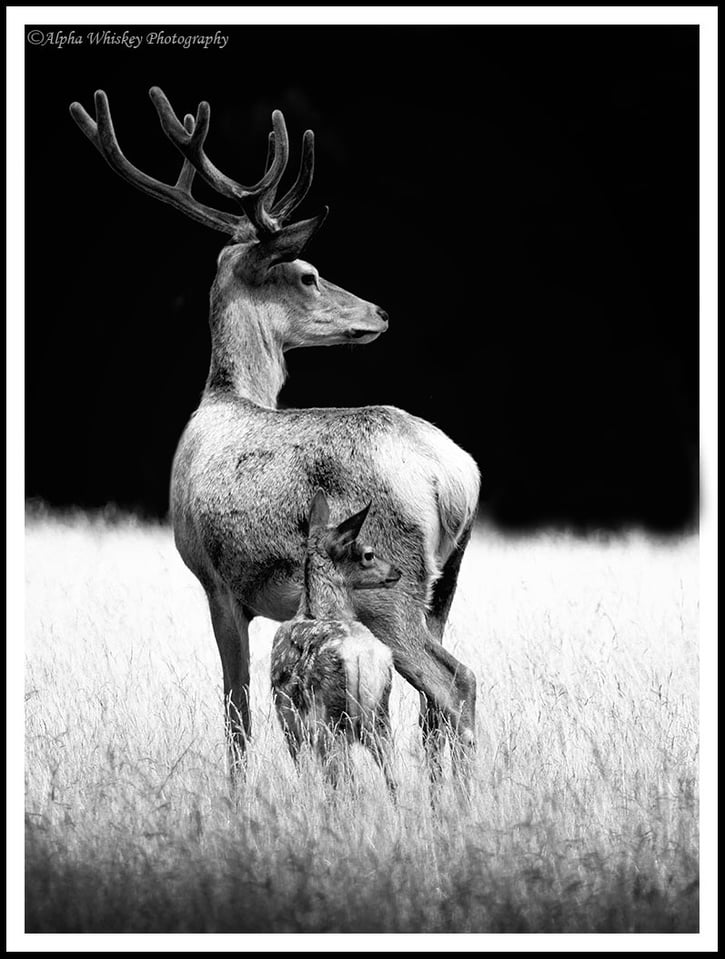

There may not be a special methodology or killer tip to producing engaging wildlife images, but I believe lighting plays a big part. How the animal is lit in relation to its surroundings can have a profound impact in how we perceive and relate to it. Even a silhouette can express the animal’s presence or character. I remember one of the winning images of WPOTY one year was merely a partial sunlit outline of a polar bear. Just a short, single orange line on a black background, but you knew immediately what it was; profound through its simplicity.

Behaviour is always satisfying to capture, and this may be an exercise in waiting for the subject to do something! It may be as subtle as a parent reassuring its young or as dramatic as two polar bears having a fight. Patience leads to opportunity, and then the unpredictability of behaviour, in all honesty, begets a flurry of shots, hoping that one of them will capture a decisive moment.

Again, knowledge of your subject will help understand their activity. For example, most big cats sleep during the day, so getting a decent shot of them being active usually involves waiting until the light is waning. Seals are very anthropomorphic in their gestures, and lend themselves to great captions.

As previous articles have suggested, rendering in black and white can remove the distraction of colour to create more impact and imposition through the clarity of lines, shapes or expression.

Another factor is eye contact. Now, I would never advocate confronting or disturbing a wild animal just to get a photo! Please don’t do that! But if you are lucky enough to win your subject’s curiosity from afar then it’s worth taking the shot at the peak of their glare. Eye contact will personalise the viewer’s experience by reeling them into the animal’s world.

One important consideration, which Nasim has rightly reinforced many times, is the post-processing. Understandably, most people would want to see wildlife in its natural glory, without any manipulation or need for enhancement. Wildlife rarely needs any make-up! But at the same time, the camera doesn’t know how you as an individual wish to represent the subject. Perhaps selective dodging and burning, or better contrast and colour can truly project the subject to the viewer.

To be sure, as many of my images have been captured of animals in captivity as they have in the wild, but usually the same rules on capturing an image apply. It is good practice to try to frame the subject in a way that belies its captive environment.

Many people, including myself, have been attacked for presenting images that were taken in captivity, as if that somehow diminished the aesthetic quality of the animal. While seeing an animal in its natural habitat is rewarding, I have stated on my blog many times that I am not claiming to offer a commentary on any animal’s environment. I simply want to capture its aesthetic and promote a greater appreciation of it through the image. I have also stated many times that I would gladly give up the opportunity to photograph any animal if its safety in the wild and protection against humans was guaranteed. Of course we know this will never be true. Soon, many of the iconic species we take for granted, such as tigers, rhino, sharks and orang-utans will become extinct in the wild. A shameful indictment on humankind’s behaviour.

Furthermore, creating engaging images of animals, wherever they may be, can surely only enhance the viewer’s appreciation of them, and perhaps promote and contribute to conservation efforts. Getting closer to the animal will help procure images that fill the frame and are more dramatic. I understand the reservations that people have with captivity, and they are entirely valid. I have been lucky enough to visit many of the top wildlife parks in the world, and almost all achieved that status by giving their animals plenty of space and enrichment. Not the same as freedom in the wild, of course, but still cared for with compassion.

Well, I hope my images here, taken both in the wild and in captivity, demonstrate that in either case it is possible to represent the beauty of life on Earth. I also hope they reflect on my commitment to capture wildlife in a way that invokes the viewer’s sympathy and compassion for the animal. Thank you for reading.

All the images you see in this article were taken with the Nikkor 70-200mm F/2.8 VRII, with or without teleconverters, and on various bodies. You can see more of my wildlife images here.

I rarely stop by to comment on the articles, but in your case I seem to be making an exception. Because the pictures are exceptionally honest and extremely beautiful. I observed that you tend to keep your images as true to the scene as possible. I liked the duel of the tigers, the chimp, the BW of the deer and the fawn among all other beautiful images.

Great images Alpha Whiskey.

Thank you Vasudeep. I really appreciate that. :)

Good articles, really helpful for me.

OK after that long debate a comment about the wildlife photography. I live in Africa where we are spoiled for choice and it is fantastic. I use a D800e and D4. I only have the 70-200f4 that I often use with a 1.4 converter on both Camera’s mostly the D4 for closer shots. I use the D800e with a 300mm f2.8 vr2 and use it naked or with the 1.4 or 1.7 TC’s. I find the TC 1.7 on this lens outstanding. I had it focus calibrated at Nikon with both bodies and the results are great. I like to take pictures with a bit more space around the animals to create context. I never try to stretch the lens by shooting to long distances. On the Open Savannah Plains you often have long shots and this is where the 1.7 is of great value. I agree it does not perform well on f4 and especially on the zoom’s including the 200-400. The 200-400 that I have used often is very sharp at a range up to about 50-65 meters. I recently went to s bird hide in one of the National parks. as I walked in there where about 15 people all armed with 600mm lenses 1Dx and D4/D4s. all focussing on a Goliath Heron. Any movement or action resulted is what sounds like machine gun fire, all taking the same picture burning pixels at 11 frames/sec. You could smell the testosterone in that hide. I sat down with my D800e and 300f2.8 +Tc 1.4, I was looked at like I fell out of a tree, coming to the same battle with a peashooter..I frames the image of the heron and then realised that even my 420mm was to0 long if you wanted to get the full bird in the frame.. The next moment the heron speared a fish and the place was in total mayhem. I managed to get 3 nice images of the bird with the fish the rest, where his wings were spread could not fit in the frame..The one guy wanted to have a look at my image in the LCD Display, had a look and showed me the image of the birds hear and half the fish..My point, It looked more like a show-0ff of equipment than anything else. After I was asked by more than a few people if the 300mm was the longest lens I owned, Yes it is..

A good article and a gallery too..

Thank you Rajesh :)

Haha, this has been perhaps one of the most entertaining posts in terms of feedback / comments. Thank you all for participating and keeping it civil! :)

Sharif, I was remiss in not adding my regards as to the quality of your pix. Very nice. And I was wondering where the damselfly preserve is. I’d like to visit some time. Apparently, the insects there are very cooperative with photographers. ;-)

Hello, David, thank you. The damselflies were shot in Richmond Park in London, the largest of our royal parks and a haven for wildlife. Not sure how much co-operation was involved as I shot that image from a distance with the 70-200mm F/2.8 + 1.7x TC. :)

Here you have a nice documentary:

Sharif,

Thank you. I look forward to your next installment.

Patrick, perhaps the word justification was an incorrect choice. Desire may have been a better one.

I also think as a participant in the heated debate I owe Sharif an apology. Sharif, you have my apology as the “football” took precedence over your great work and the real point of your article.

I too have my character faults. Ire goes up whenever I encounter someone who only sees one side of any situation whether it is right or left. Black and white are only two ends of the spectrum…We all must consider the grey in between. As photographers, we all understand the value of grey.

Dear Mike, no apology necessary as no umbrage was taken, but thank you and to Patrick for your graciousness anyway :)

As I indicated above, I believe everyone is entitled to air their views and engage in a spirited debate. We can only make progress in this world by airing out the issues rather than bottling them up.

I had anticipated before writing this article that it might be controversial, as wildlife enclosures are always controversial for many. But I don’t believe in hiding from a rebuke or surrendering to the discomfort of some, especially when it was never my intention to upset or offend anyone by writing this piece :)

And, like yourself, I don’t take absolutist positions on such issues, but try to understand and respect the views of others, especially if I disagree with them. And if I disagree, I try to do so with the courtesy and grace that I would want shown to me :)

I am glad that some people enjoyed the article in the spirit in which it was intended. That is reward enough. I hope I can contribute more in the future :)

Warm Regards,

Sharif.

David Meyers, I am in agreement with your thoughts. First, yes, that was one strange trip!

Truly, wild life and wildlife have two meanings which become a philosophical determination depending upon one’s natural and political perspective. Sharif photographed all wild animals, whether in the wild or wild in a preserve or zoo they are still wild and not domesticated. There is no end to the truth that Patrick O’Connor, brought up that human advancement, encroaching on wild habitat, is spoiling the range of certain species. Therefore, is it wrong to capture them, try to increase their numbers by breading in partial captivity in order to save that particular species? My opinion is this is a good thing. The Chinese have been breeding and releasing Pandas into the wild for many years with some degree of success.

Whether or not the character of “Betty” was real or not is not germane to much of what was written by that person. I am sympathetic to the plight of many species that may go extinct. I am equally sympathetic to the plight that the human species may also go extinct should we not pay attention to the world’s situation; which was aptly noted by Patrick. I have a t-shirt with the slogan; “it is what it is”. Not that this attitude is correct but it is a fact. The growing world requires more of everything. Technology can produce enough if given the chance and it stands to reason that endangered species can be saved utilizing compassion and technology in the same manor. However, in some cases that may not allow for re release in the “wild” and preserves, managed by humans may be necessary so our children will know what an orangutan looks like in real life. Having said that, I will stand as saying if I have to decide between some wild species extinction and human existence, I will side with human existence.

We can’t have everything our way unless we can construct a perfect world. When in college my philosophy professor told us this. “Three things govern your life; the way things ought to be; the way you want them to be; and they way they are. The way they are is all we have to deal with unless we can effect change to something else”. Just my .02.

That was my fault as much as anyone else’s. I should have kept my mouth shut (er… my fingers away from the keyboard). Sorry, to everyone and especially Sharif, for the distraction.