In the aftermath of events in Israel and Gaza following October 7, 2023, the entire world, including the U.S., has witnessed a wave of protests unlike anything since the summer of 2020 after George Floyd was killed by police. Photo images of these recent protests have appeared in the major media but are even more pervasive in the various platforms of social media, notably Instagram, X (Twitter), and Facebook. Although such images are routinely included in the reportage about these events, protest as a genre of photography seems to be a neglected area of discussion among photographers and scholars of visual culture.1

Indeed, collective action seems ready-made for photography. Images of protest events convey drama and emotion in much the same way as other more familiar photographic genres. Influenced by the recent wave of protest activity, especially on university campuses, this article for Photography Life represents an effort to forge a contribution to the topic of protest photography, and to stimulate discussion among PL readers about best practices along with commentary on the genre itself.

My own stake in protest photography stems primarily from my work teaching University courses on Palestine / Israel, and “Protest and Social Movements.” For the past 20 years, I have made a point of photographing protests locally and abroad, as visual teaching supplements to more traditional kinds of texts, with the photo below gracing the title page of the syllabus for my “Protest and Social Movements” course. Over the years of photographing protests in many different contexts, I have come away with arguably a few decent images and some observations about this genre.

In a sense, protest photography incorporates some of the most storied traditions in the photographic arts. Vistas of large crowds recall the power of landscape photography; the individual emotion of protestors harkens to portraiture; visual documentation of protest events, some of which become newsworthy, beckons to photographers as photojournalists and documentarians; the fact that protest generally takes place on the street reveals the influence of street photography.

All of these photographic genres have certain conventions in terms of aesthetics and technique, but what they share is that all of them enlist visual imagery to tell a story about people and the world. Protest photography is no different. It enlists visual imagery to tell a story about people seeking social change. More dramatically, protest photography itself has been a change agent. Some of the most iconic photographs ever taken – the self-immolation of the Buddhist Monk Thich Quang Duc in 1963 taken by Malcolm W. Browne comes to mind – depict acts of protest that circulated around the world and changed the course of history.2

Table of Contents

The Crowd: Landscapes of Colletive Action

Protest, as a collective activity, is a register of a perceived injustice that protestors wish to convey in a public space. Arguably the most distinct visual element of protest is the crowd, above all its size and its social and demographic attributes. In terms of photography, the crowd seems most akin to a kind of landscape. Instead of the elements commonly associated with landscape, however – mountains, water, deserts, forests, flora, fauna, etc. – it is humanity as a collective form that is the defining visual element of the protest landscape.

Conveying the size, composition, mood, and even the “kinetics” of the crowd at demonstrations are among the primary aspects of what photographers aim to capture in the course of a protest event. There are undoubtedly different techniques for accomplishing this aim but for myself, as a photo practitioner still learning new things about the art, I generally rely on some of the most obvious aspects of landscape photography. Above all, this would include apertures of at least 8, and mostly 11 and sometimes even 16 depending on the light so that the entire image is in relative focus, similar to what the eye actually sees in the spirit of the great Brazilian documentarian, Sebastião Ribeiro Salgado.

From the Crowd to the Individual

At the same time, depicting the crowd is only one visual expression of the protest. Invariably, individual protestors stand out in terms of gestures, facial expressions, energy levels, and interactions with other demonstrators. Arguably, however, some of the most dramatic moments of protests occur when individuals encounter and confront authority, namely police or even military. In this regard, one of the most compelling images I have taken comes from the series below of a young boy from the Palestinian village of Bil’in.

From 2005 – 2017 villagers from Bil’in organized a weekly march every Friday to protest the Separation Wall built by the State of Israel on village land. The march would typically include 500 – 800 villagers, and some Israelis who came to protest with them, along with international observers such as myself. The protest would begin at the local mosque and wind through the village to the area of the Wall where Israeli soldiers were always stationed, and encounters between protestors and soldiers would invariably take place. I witnessed 10-12 of these marches in Bil’in over the years and almost every one of them was broken up by the Israeli military with tear gas, rubber bullets and at times live ammunition that killed two villagers.

The young boy in the two images below was often in the front line of the protests, but on this occasion he deviated from the usual route of the march and backtracked to confront a group of the Israeli soldiers near the Wall. Teargas was already being fired at protestors. I decided to follow this young person and admittedly I was nervous for him and myself. Both of us could have been injured, but on this occasion the youngster endured nothing more threatening than a bit of verbal abuse from the commander and I was able to record his exploit.

Similarly, on June 26, 2004, I witnessed one of the very first protests by Palestinians against the Wall in Ar-Ram just outside Jerusalem. Protestors in this case organized a march that passed by columns of concrete, staged on the main road in the center of the town for placement in the ground to form the Barrier. Just as the march passed these concrete slabs (below), the Israeli military and border police attacked the protestors with tear gas and rubber bullets and I watched them beat and arrest the protestor in the second photo below.

There is admittedly an epilogue to the photo of the person arrested (above). There was a contingent of Israelis at this protest and when the protest concluded, as the Israeli group was waiting for a bus to take them back into Israel, they held a meeting and asked if anybody had photos of the sequence of events just prior to the arrests of demonstrators to use as evidence in Israeli courts proving that the marchers had been peaceful and were unlawfully detained. I provided them with my photos and heard from the group later that my images of the protestor above enabled him to be released from detention. I also learned his name and where he lived and we met one year later.

Signs

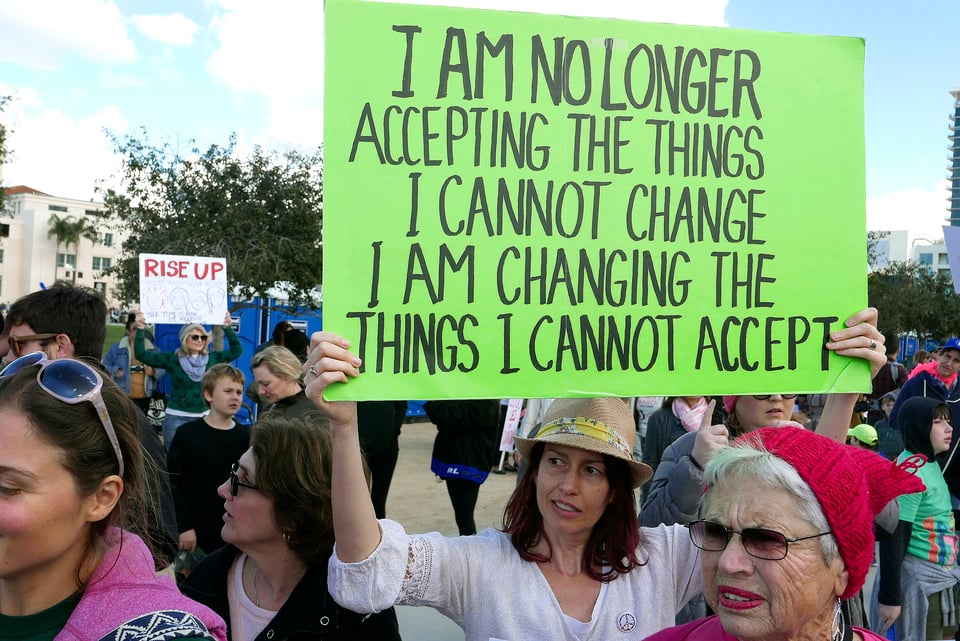

One of the most compelling attributes of any protest are the signs carried by protestors which provide some of the best visual testimony about the message that the protestors wish to convey. I have also used photos of signs in my “Protest and Social Movements” class to help illustrate complex theoretical ideas about collective action in the scholarly literature. In my experiences, the most extensive, as well as the most creative signage I have seen at protest marches comes from the various Women’s March protests during the Trump Presidency where crowds formed a sea of signs.

In addition to the vast panoramas of signage at these demonstrations, the Women’s Marches produced an extraordinary collection of clever, poetic, sarcastic, and even caustic messaging from protestors of which the images below are but a small sample.

Protest as Outcome

Finally, there is invariably a beginning, middle, and conclusion to protest events that may last a couple of hours, or can unfold over days and even longer. Capturing this sense of time from the opening moments of the protest to an outcome enables the protest photographer to convey a more complete story of the event.

In what follows, I focus on three very different protests that I have photographed in an effort to narrate a story in each case from an opening moment in the event, to a moment of finality. The aim in this section is to highlight different photographic genres embedded in protest photography, along with the varying spatial and human scales that protest photography captures. These examples also highlight the different time frames in these particular cases, from hours to days, marking the opening moments of the protest to what is often a dramatic conclusion.

George Floyd, San Diego 2020

Nablus, Palestine October 2023

Ten days after October 7, 2023, when Israel began to intensify its bombing campaign in Gaza and its raids in Palestinian West Bank cities, protest marches against this violence began to take place in the Palestinian cities of Nablus and Ramallah. For the Fall term of 2023, I had scheduled a sabbatical trip to Palestine to complete fieldwork for a new book I am writing on Landscapes in Palestine. I arrived in the West Bank for my sabbatical on the evening of October 6th. The next morning, I awoke to a changed world.

It was impossible to move around immediately after October 7th, but in a couple of weeks I managed to find ways of reaching places where I wanted to be and one of them was the West Bank city of Nablus. Residents of Nablus began to organize protests against what was unfolding in Gaza along with the general conditions of siege imposed on the City and the West Bank.

One of the primary issues of taking photos in any protest situation is safety and in this particular environment, I was particularly aware of the safety risks with the possibility that the Israeli military could enter the City and forcibly break up any demonstration. At the same time, I was also aware of risks, as a foreigner, in taking photos of Palestinian protestors. For this reason, I wanted to be as inconspicuous with my camera as possible. Consequently, I decided not to use my preferred travel camera – a Sony A7c ii – but instead my almost iPhone-like Lumix LX 100 ii which is what captured the images below. It turned out, however, that this was not a problem at all.

Encampment: University of California, San Diego

Students at the University of California, San Diego, much like students at 150 other U.S. college campuses, followed the example of Columbia University and established an encampment on May 1st to protest against what they considered a genocide against the Palestinians of Gaza. They were also protesting the complicity of the U.S. government in aiding this assault, along with the culpability of UCSD in providing research for some of the weapons systems used in the Gaza campaign and financial support to the State of Israel through its investment portfolio.

There were differences of opinion on the campus about this protest. Students overwhelmingly supported what encampment protestors were doing as a right of free expression and as part of a longstanding heritage of student protest against injustice. Faculty was very much split. For its part, the Administration was against the encampment from the very beginning. Based on what had transpired at other campuses, it seemed likely that the Administration would use police to dismantle the protest and arrest the students.

The encampment survived for five days during which time students slept in tents, held teach-ins on various aspects of the conflict in Gaza, held rallies in support of the encampment, and even had a Friday Shabat service and dinner presided over by a local rabbi. On Monday, May 6th, the Chancellor called on three different police forces to clear the encampment and make arrests. The following images tell a small part of this chronology, bookended with the image immediately below when the encampment was established on May 1st to the final image when police stormed and dismantled the encampment.

Final Thoughts

Protest events beckon to many storied photographic traditions and enable photographers to enlist a range of techniques in telling stories about a phenomenon that is an integral part of cultural and political life worldwide. At the same time, protest photography, despite its ubiquity in the reporting of protest events, and its role as a change agent itself, seems to be an under-appreciated genre of visual culture. This article represents a modest contribution to elevating the visibility of protest photography among photographers in the hope of sharing examples of the genre, and encouraging discussion and critical reflection of techniques and best practices among practitioners of the craft.

1 One notable exception is the popular online photography commentary of Tony and Chelsea Northrup who, during the George Floyd protests of 2020, created an extremely informative video about protest photography as a genre.

2 See “It Felt Like History Itself: 48 Protest Photographs that Changed the World.“

After Hamas raped, tortured, burned, kidnapped, and murdered innocent Israelis on October 7, the worst genocidal act against Jews since the Holocaust, it is astonishing to see how so much of the world has turned to blame the victims and reignite the historic scourge of anti-Semitism.

To Alexander Sergeivich,

There is nothing in your comment about the content in my article, and therefore I don’t want to spend time giving your comment any legitimacy. There is a principled way to engage with the content in Photography Life, but sadly you have chosen not to follow it.

The most incredible thing that I’ve seen since October 7th is how many fellow Jews are standing up with the Palestinian cause – from academia to Ultra Orthodox. Nazinyahu and his AIPAC dogs can no longer hide their real agenda, which is to take over all of Palestine, and then move on to the “greater Israel”, which includes all of Lebanon, Syria, and even part of Saudi Arabia. Noam Chomsky and other scholars talked about this many times in their lectures.

Settlers already started dividing up the land in Gaza, and there have been attempts to sell land lots right here in the USA. They want to bulldoze old structures and remaining Palestinian homes, then build settlements, the same way they’ve been doing it for many years in the West Bank.

Thank you Gary for being on the right side of the history. From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free!

Aaron, Thanks much for this heartfelt message. Indeed there are many of us on the right side here.

After Hamas raped, tortured, burned, kidnapped, and murdered innocent Israelis on October 7, the worst genocidal act against Jews since the Holocaust, it is astonishing to see how so much of the world has turned to blame the victims and reignite the historic scourge of anti-Semitism.

Thank you Photography Life for publishing this superb piece. The world has certainly changed, and we now know the mainstream media is just full-on propaganda. The truth always prevails, and now we know who is behind the lies and atrocities. Been following Noam Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, John Mearsheimer and a few others, some of the greatest minds of our time that speak the truth.

Gary, I’m glad to see you and a few other notable university professors in their ranks!

Eric, Thanks so much for your kind words about the article. Indeed, it seems you are following things quite closely.. Believe me, I”m not alone. There are many like me speaking out and writing — and taking photos to present a different kind of picture!

Thank you for a great article, for amazing pictures, and for being a witness to important events in our world. Really inspiring!

Gary, thank you for posting this article. Amazing content, and very inspiring work. Thank you for sharing… I will be following your work. Looks like you know the region better than most people out there! How many times have you been to the West Bank and Gaza?

I really hope Israel stops what it is doing sooner than later. It is heartbreaking to see so many dead and crippled children, all in the name of “defense”…yeah, we’ve heard that, as well as “weapons of mass destruction” and a bunch of other nonsense before (Iraq, Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, Vietnam, etc). So sad that the world can sit and watch these atrocities. I am glad that many are starting to speak up. Keep up the good work sir!

John,

Thanks for your kind words on the images and your thoughtful reflections on the state of things in Palestine. I know the region quite well because it is central to my work as an historical geographer. For the past 15 years I have been making regular trips to Palestine, and photography has become a critical piece of my writing on the Palestinian landscape. As you might expect, protest has become a very visible phenomenon on this landscape and I have tried to represent what I have seen and encountered in an objective way. Thanks again for your thoughts on the piece.