As a wildlife photographer, capturing the world’s immense variety through your lens is undoubtedly a romantic idea. But no lens does it all, which is why manufacturers offer so many – from 9mm fisheyes to 1200mm supertelephotos. Which one is right for you? It starts with the critical choice between a prime and a zoom.

Table of Contents

Prime and Zoom: The Basic Characteristics

One of the fundamental characteristics of any lens is its focal length, typically measured in millimeters. The rule is simple: As the focal length increases, the field of view of the lens narrows. In other words, a long focal length like 400mm or 600mm can bring distant subjects into sharp focus. Whereas a wider focal length like 24mm or 50mm requires you to get much closer to your subject in order to fill the frame.

With primes, the field of view is fixed (for example, a 500mm prime offers a 5° view of the world in front of you), while with zooms, it can span a range (a 180-600mm zoom covers about 14° on the wide end to 4° on the narrow end).

Certainly, in theory, having a zoom is more flexible than having a prime. But from this difference between primes and zooms, many other practical differences arise, and a lot of them favor primes. Let’s take a closer look at everything below.

Note that to keep this comparison as straightforward as possible, I will only focus on longer focal lengths, which are most commonly used in wildlife photography – anything from 200mm up.

Maximum Aperture

Many photographers willingly endure the torture of lugging heavy telephoto lenses over rough terrain, even when lighter alternatives exist, for one simple reason: maximum aperture. In other words, the speed of a lens, or its low-light capabilities.

Lenses with a wide maximum aperture like f/2.8 or f/4 allow for more background blur compared to shooting at, say, f/5.6 or f/6.3. They also capture more light, making it easier to continue shooting even as the sun dips below the horizon. Also, a bright maximum aperture delivers more light to your camera’s autofocus system, so it becomes more likely that you get accurate focus even in low light. In short, a wide maximum aperture is highly desirable in wildlife photography.

NIKON Z 9 + NIKKOR Z 400mm f/2.8 TC VR S @ 400mm, ISO 16000, 1/125, f/2.8

The reality is that prime lenses usually have wider maximum apertures than a zoom lens of the same focal length. There are many 400mm f/2.8 or 600mm f/4 prime lenses. With zoom lenses, you may need to make due with f/5.6 or f/6.3 instead.

Of course, there are outliers in both camps. On the one hand, there is the portable but painfully slow Canon RF 800mm f/11 IS STM. On the other, there’s the gigantic Sigma 200-500mm f/2.8 zoom. (If you manage to get your hands on one, don’t forget to bring a cart – you’ll need it for its 15.7 kg / 34.6 lbs whopper.)

Under normal circumstances, however, primes are brighter than zooms, especially for a given price. For example, the Nikon Z 400mm f/4.5 S and Nikon Z 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 S are both great lenses about the same price, but the prime offers f/4.5 at 400mm, while the zoom is two-thirds of a stop slower, offering f/5.6 at 400mm instead. Or, if the maximum aperture is the same – like the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3 versus the Nikon Z 600mm f/6.3 S – then the prime will almost certainly be smaller and lighter, and usually sharper as well.

That brings me to the next comparison…

Weight and Dimensions

One of the interesting differences between prime and zoom lenses is their portability. But the differences don’t always favor one over the other. In fact, there are heavy zooms, heavy primes, light zooms, and light primes.

To illustrate the difference between primes and zooms, let me compare three lenses, all of which can reach a focal length of 600mm.

First is the Nikon Z 600mm f/4 TC VR S. This lens tips the scales at 3,260g (7.2 lbs). It’s actually not bad considering that 600mm f/4 lenses in the past used to weigh much more – sometimes nearly twice as much. Still, it is a heavy lens.

Second is the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3 VR zoom. This zoom lens weighs just 1,950g (4.3 lbs), and it’s clear which lens you’d rather carry on a hike. The reason that it’s lighter is not because it’s a zoom, though. The reason is that the maximum aperture is a narrower f/6.3 rather than a wider f/4.

Third is the winner: the Nikon Z 600mm f/6.3 VR S. This lens is a featherweight champion at just 1,470g (3.2 lbs). It shares the same f/6.3 maximum aperture as the 180-600mm zoom. However, since it does not need to zoom, Nikon was able to make it lighter than the 180-600mm.

This goes to show that it is not directly the case that a prime lens will always be smaller and lighter than a zoom, or vice versa. Often, the biggest factor that determines a lens’s size is the maximum aperture. However, if the focal length and aperture are the same, a prime lens will usually be lighter than a zoom.

Another example supports this point. Of the popular pair of Nikon AF-S 500mm f/5.6E PF ED VR and Nikon AF-S 200-500mm f/5.6E ED VR, the prime is an impressive 840g (1.9 lbs) lighter than the zoom.

So, if you have in your head that telephoto prime lenses are monsters, it’s probably because you’re thinking of exotic lenses with maximum apertures of f/2.8 or f/4. All else equal, prime lenses usually have an advantage here.

Sharpness

Lens sharpness is often overrated, especially with supertelephotos. If your wildlife photos are not crisp enough, it is usually due to factors like motion blur, focus errors, atmospheric distortion, or excessive cropping. Lens sharpness is pretty far down the list. However, if you do everything else right, a sharper lens still helps, and a mediocre lens can be noticeable. Most of all, you’ll have some more room to crop with a sharper lens, especially if used in combination with a higher resolution camera.

Typically, primes are more sharp than zooms. This is apparent in a lab environment, and it’s sometimes clear in the real world, too. Although, the differences depend significant upon which lens you’re considering.

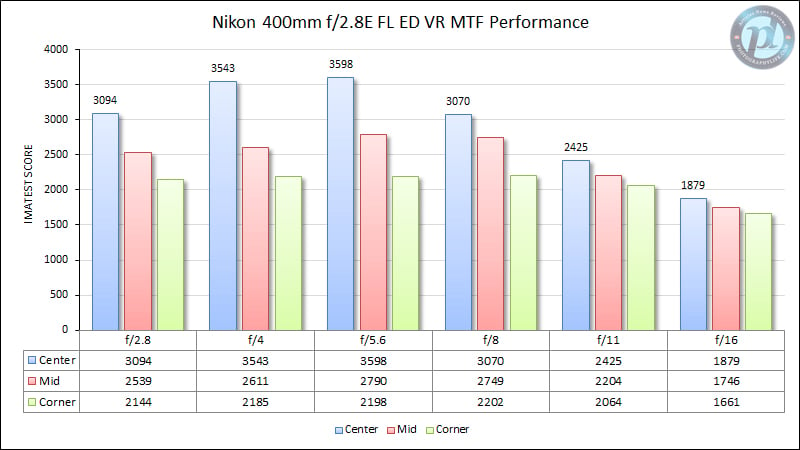

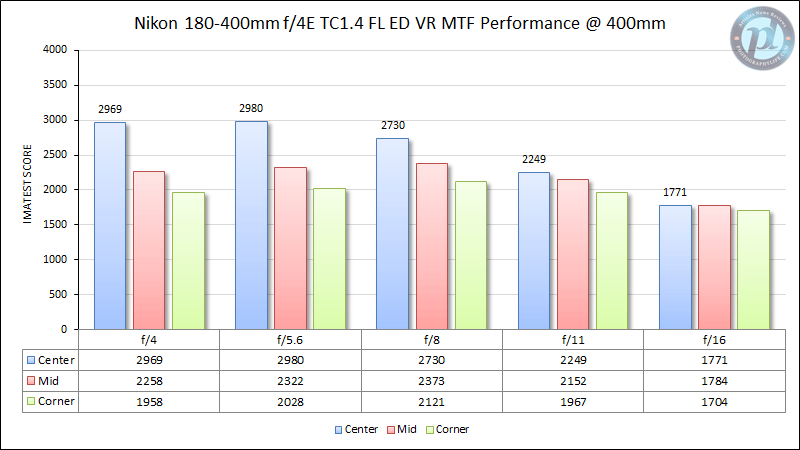

For example, let’s take a look at how the Nikon 180-400mm f/4E TC1.4 FL ED VR compares to the Nikon 400mm f/2.8E FL ED VR at 400mm. Both lenses are in the top class of Nikon F-mount telephoto lenses and showcase the best of what Nikon was capable of at the time of their introduction.

Although the zoom delivers solid performance, the center sharpness of the prime lens is about 20% higher at f/4 and f/5.6, where most wildlife photography is done. This is enough to see a difference in real photos if everything else is optimized.

However, I don’t think that sharpness should be your primary consideration when picking a lens. If you need the versatility of a zoom, don’t be scared off by this difference. It’s better to have a good composition from a zoom than a badly composed photo from a prime, no matter which one is a little sharper.

Minimum Focusing Distance

Most photographers use telephoto lenses to bring distant subjects closer. But what’s often overlooked is their ability to magnify small subjects that are close by. You could argue that there are dedicated macro lenses for this purpose, and you’d be absolutely right. BUT…

Macro lenses typically have focal lengths around 100mm, which presents a few challenges. First, there’s the issue of working distance – the gap between the lens and the subject. Very few creatures will tolerate a lens hovering just inches from their antennae, beak, or nose. A telephoto lens increases that distance, reducing the likelihood of triggering a flight response.

Second, 100mm or even 200mm macro lenses can be great if you want to include an attractive background. But if the background is distracting, you’ll have a much harder time finding an angle that hides it. Telephoto lenses, on the other hand, make it easier to control the background and use it to fine-tune the overall character of an image.

The ability to focus on close subjects is, in my opinion, a huge advantage for any lens. Interestingly, large exotic primes often lag behind zooms in this regard. Let’s compare the Nikon Z 400mm f/4.5 VR S with the Nikon Z 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 VR S. While the prime can focus down to 2.5m (8.2ft), the zoom manages to focus down to just 0.98m (3.2ft) at the same focal length. In practice, that’s a huge difference and a strong argument for the zoom.

Not all lenses will have such a dramatic difference, and occasionally, the difference will favor the prime (such as Nikon’s famous 300mm f/4 F-Mount lens that is nearly a macro lens). Still, if you plan to use a single lens for a wide range of subjects – from tiny creatures like insects and amphibians to birds and larger mammals – pay attention to the minimum focus distance – or the maximum magnification spec – of the lenses that you’re considering. Often, a zoom will have the advantage here, both for its ability to change focal length and for its closer minimum focusing distance.

Mechanical Durability

The more mechanically complex a device is, the greater the chance that something will fail at some point. This is as true for cars as it is for lenses. And the fact that zooms are mechanically more complex than primes shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Unfortunately, this isn’t just a theoretical concern – it’s something I’ve seen firsthand. Not long ago, I was dealing with a friend’s camera whose zoom had jammed, leaving it usable only within a narrow range of focal lengths. Generally speaking, primes are more mechanically durable than a similar zoom.

Another common problem with zooms is that many of them extend in length while zooming, which can such in dust. Some of this dust ends up on the camera sensor, and some ends up in the lens. It can also be a problem if shooting in heavy rain or snow, even with a weather-sealed zoom. Before retracting your zoom lens, I recommend wiping down any extended parts to prevent water from getting inside.

That said, some zoom lenses avoid this problem entirely by maintaining a constant length, such as the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3 VR, Sony FE 200-600mm f/5.6-6.3 G OSS, or Fujifilm XF 150-600mm f/5.6-8 R LM OIS WR. These lenses take up more space in a backpack, but in addition to greater mechanical durability, they are easier to balance on gimbal heads. (Meanwhile, a handful of telephoto prime lenses extend when focusing, but this is very rare these days.)

Autofocus Speed

Although zooms are thought of as slow, there are zooms out there whose focusing speed is phenomenal. As I write this, I am thinking of the Nikon AF-S 70-200mm f/2.8E FL ED VR and photographing puffins and skuas in Norway. At the time, I had this pro zoom with me along with the Nikon AF-S 200-500mm f/5.6E ED VR. As much as I like the latter lens, comparing their focusing speed is like comparing the speed of a racehorse and a pack mule.

But if focusing speed is an absolute priority, wide-aperture primes will typically be the leaders of the pack. They have fewer elements to move when focusing, and – if their maximum aperture is brighter – they can cast more light on the camera’s AF module. The more expensive exotics also have the most powerful AF motors available. In Nikon’s latest 400mm f/2.8 and 600mm f/4, the motors are so powerful that their magnetic field can interfere with the proper functioning of pacemakers (official Nikon warning).

It is certainly possible to take photos like birds in flight with prime lenses. In fact, the biggest differences in focus speed are usually down to how modern and expensive a lens is, not whether it’s a prime or zoom. But at the margins, a prime usually has a bit of an advantage in this comparison.

Filters

Just like in landscape photography with standard lenses, filters can sometimes be useful for telephoto lenses as well. Creative filters, such as polarizers or ND filters, are the most common choices. Alternatively, you may want to screw on a simple UV filter to protect the front element of your lens.

Often, supertelephoto lenses cannot take filters directly on the front threads. Instead, you must drop the filter into the rear drop-in slot on these lenses, which isn’t as flexible of a solution.

Whether a telephoto lens takes filters or not is mainly a factor of its maximum aperture, not so much whether it’s a prime versus a zoom. However, zooms usually don’t have as bright of a maximum aperture, and relatedly, they usually have smaller front elements. This makes it easier to use standard filters.

For example, the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3 and Nikon Z 600mm f/6.3 both take standard 95mm filters, while the Nikon Z 600mm f/4 TC VR S does not.

Versatility

If there’s one area where zoom lenses undeniably dominate, it’s versatility.

With wider lenses – say, a 35mm lens – it’s easy to change the size of my subject by walking forward and backward a little. In wildlife photography, however, things are a lot less simple. Small adjustments in shooting position don’t have nearly the same impact when working with a telephoto lens as they do with a wide-angle lens.

On top of that, wildlife photographers are often shooting from a blind (or, alternatively, some hard-to-reach position) where moving forward and backward is simply not an option. Many animals will be wary if you move too much, so you are often fixed in one place.

Thus, the ability to change focal lengths with a zoom often mean the difference between getting and not getting the shot. Combining this with the closer focusing of many zooms, and sometimes their lighter weight, and they have the potential to be a lot more versatile than a prime. Simply put, they can shoot a greater variety of subjects with a greater variety of unconventional angles.

Price

The price of a lens varies greatly – it doesn’t always favor primes or zooms. However, I would say that prime lenses have a slight advantage here with wider focal lengths (compare a 50mm f/1.8 versus a 24-70mm f/2.8). Meanwhile, zooms catch back up in the telephoto range and sometimes have the advantage.

For example, the Nikon Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3 is $1900 cheaper than the Nikon Z 600mm f/6.3 S, even though both lenses reach the same focal length and maximum aperture. And the most expensive telephotos from many manufacturers are prime lenses like a 400mm f/2.8 or 600mm f/4. The “budget” choices for supertelephotos are usually going to be zooms.

Conclusion

So, which is better for wildlife, prime or zoom? It turns out, there is no simple answer. For example, if you photograph small birds, long prime lenses (500mm to 800mm) will probably serve you better than a zoom. With the zoom, you’ll probably find that you’re using it at its maximum focal length most of the time anyway – and then cropping even further in post-processing.

If you photograph everything from birds to larger mammals, a zoom might be superior. Especially on an African safari or similar adventure, a zoom is invaluable. Its ability to adjust the angle of view to the size or distance of the animal is unmatched. That is, unless you have the luxury of two cameras with two primes.

Do you also want to capture landscapes with your telephoto lens? A telephoto zoom would allow you to compose much more precisely. A prime would mean zooming with your feet, and this in turn might mean traversing entire mountain ranges with telephoto lenses. Or, alternatively, needing to crop or make a panorama to change the composition that you captured.

And what if we include not only distant animals, but also small creatures like lizards in our considerations? Then zooms almost always win. If you don’t want to carry a dedicated macro lens, some zooms let you focus very close indeed.

So, in what ways are prime lenses better than zooms? It’s often a matter of subtle nuances that can make all the difference. Generally speaking, when their focal length is ideal, primes usually offer better performance than zooms. A wider aperture, faster autofocus, better bokeh, higher sharpness – these are all areas where primes usually outperform their zooms.

You may be wondering which lens I use most often. Well, the Nikon AF-S 500mm f/4E prime! I felt that the combination of price, weight, image quality, and features was ideal for my bird photography. However, if someone replaced it one day with a 180-600mm, or any other lens, I could not complain. After all, people take remarkable wildlife photos with any lens. The most important thing is to go outside to take pictures. The rest will fall in place no matter what lens you have.

So, prime or zoom? That’s the eternal question. I hope my article shed some light on this topic. Either way, as always, I’d love to hear your insights in the comments below the article.

I have a Sony 100-400 GM which is my bread and butter outdoor sports lens but can be a bit short for wildlife. I use it on a Sony A9.

To get a bit more reach, I have identified the following options (in ascending price order):

1 – the Sony TC 1.4x. It works apparently reasonably well on the 100-400, resulting in a 140-560 5.6-8 equivalent lens. Smallest and lightest option for sure.

2 – the Sony 200-600 G, marginally faster (and probably sharper) than the former but at the cost of increased size.

3 – the new Sigma 500 5.6 which seems fantastic but not that much longer than the 400mm I already have.

4 – the new Sony 400-800 G, but I am afraid its size means I would leave it at home.

5 – a Sony A1 (probably a used Mk I) to get a bit more cropping ability. The APS-C mode still offres 21Mp and turns my 100-400 into a 150-600 equivalent.

I am most tempted by the two extreme options of the scale but would be interested in your opinion.

Personally, I would avoid TCs on zooms. They work reasonably in the lab but fall apart in the field with fine feather detail. f/8 at 560mm will be quite dark, compared to the 200-600. Personally, I’d go with the Sigma or the 200-600. An A1 with a 100-400 and cropping will still reduce the effective light-gathering, i.e. an A9 with a 200-600 will get much better quality in lower light than a cropped A1 with a 100-400, even though you get approximately the same pixels on target.

And 500 is a significant change from 400. It’s a 1.25 crop, quite a lot in my opinion when it comes to birds. Such a linear crop factor can often make the difference between reject and not, esepcially given that the 500 will be sharper than the 100-400 at the long end.

So, 500 or 200-600 is my recommendation.

I have a z6iii. If I want to add a telephoto prime, would you recommend buying a new 500 PF or go with Z telephoto like 600 f6.3/400 f4.5? Does 500pf allow for lens button customisation?

I have shot a lot with 180-600 and honestly don’t like carrying it for long durations.

I have the 500PF and I would recommend the 600 f/6.3 instead…if you can take the price difference. Don’t get me wrong, the 500PF is a great lens, and it works great on my Z8, but 600 is a 6/5 = 1.2 linear crop, which is handy. The 400 f/4.5 is good but short IF you’ve been shooting mostly at the long end of the 180-600. The only advantage of the 500 f/5.6 is that it has a shorter minimum focus distance than the 600PF, 3m vs 4m, so for some closer situations, the 500PF is superior. The 600 has synchro VR for bodies that support it. The 400 f/4.5 is not a PF lens and the smallest and lightest so that would be ideal if 400 is your ideal. As for button customization, not 100% sure about that. I think it must at least be camera-dependent because the buttons can’t be changed from the 3 possibilities on my Z6. I’ll check my Z8 if Libor doesn’t answer first….

Thanks Jason. 600 6.3 is a bit of stretch for me as of now. Probably will start saving for it instead of maxing out my CC.

Good analysis, Jason. Regarding the button customization, I’m not 100% sure how it works on the 500mm f/5.6 PF, but my 500mm f/4 E lets you customize the four buttons on the front of the lens (L-Fn in the camera menu). I expect, the PF lens will be the same. For the function you assign in the camera menu to actually activate, you need to set the switch on the side of the lens to the AF-L position. The remaining “Memory recall” and “AF-ON” are hard-coded lens functions and cannot be changed.

I would always pick a prime over a zoom lens provided I know my subject behaviors and rough estimate of distance I will be from Said subject. Zooms, while versatile leave a bit to be desired when it comes to IQ and Focus speed. Personally, if I am spending time in the field capturing wildlife, I want to come home with the best IQ possible. Only Primes deliver here . YMMV

I feel the same way. That’s why I sold the 180-600mm and bought a used 500mm f/4 instead. It’s definitely a step up in image quality, unfortunately I can’t say the same for autofocus. But this is not a question of zoom vs prime, but simply the new generation of motors on Z lenses are tuned for today’s cameras.

Putting aside price for the moment…..I always use(d) primes for wildlife…on film. When digital came out I (we) quickly found out that we could use zooms with good results and, even more recently, use zooms with much closer or on even par with primes. As for variable f stops compared to fixed, with digital it’s become even more convenient by just adjusting the ISO. Personally, I still do prefer a prime, but I feel that’s because of how I’ve always felt with them. Lately though, I find myself grabbing a zoom yet always have a prime close by. Just in case I feel….nostalgic. As for price, I’ve never worried about that…yet. then again, I already have what I need so…. my 3 main primes are a 300mm f2.8, 400mm f3.5 and 500mm f5. Really love these lenses

I think Tim, you’ve added another piece to the puzzle. Many photographers (myself included) prefer to reach for a prime lens purely for sentimental reasons. Most of my photos are not published other than on the web, where the slightly greater sharpness of prime lenses simply disappears. Still – for the good feeling in the field, and for the pleasure of seeing all the fine detail in the feathers – my heart usually picks a prime lens.

For many of us, I think the choice between primes and zooms is co$t..😉 I bought my Nikon 200-500mm f/5.6 several years ago because it was the only way I could afford 500mm. I use the 500mm 95%+ of the time. At the time, a 500mm prime was somewhere in the $10,000+ range; way out of my budget as a serious, but “hobbyist” photographer. Nikon apparently realized that most of us were not using the 200-500mm as a zoom, but as an affordable 500mm lens. They subsequently offered the 500mm f/5.6 prime for about $3500; a much more manageable price than the existing telephoto primes.

The optical performance of most modern lenses- including zooms- is so good that for many (most?) of us amateur/hobbyist photographers, cost is a primary factor in our choice.

IMHO

As an amateur enthusiast not subject to professional demands, I found satisfactory the combo quality zoom plus teleconverter, applying software based on IA in post.

After many comings and goings (many GAS-driven…), I found peace (and less weight) in FF Nikon 70-200/4 plus Nikon TC 1.7 and APS-C Fujifilm 70-300 plus TC 1.4.

Here’s a newbie (to wildlife, not photography) take: until one gets used to finding an animal, a small animal, with a long prime, with a zoom you can quickly pull back, locate, lock the AF point, then zoom in. Of course you’ll miss some action. That was my experience recently when renting the Nikkor 180-600. I love wildlife, but I am not a wildlife photographer, and it would take many hundreds of images to learn behaviour and movement patterns to go out with a 400 or 600 or 800 prime. Sexy as they may be.

That’s a good way to put it. When someone is more familiar with an animal’s behavior patterns, a prime may be more appealing. Otherwise a zoom could give some more flexibility.

The technique you describe can be quite useful in the beginning. But over time you will learn to see the world through the narrower field of view of a telephoto lens and finding your subject in the viewfinder will become faster. Sometimes the problem can be the shallow depth of field of telephoto lenses. My little tip is, focus at a similar distance to where the animal you want to photograph is. It will be easier to find then. This is especially true for birds in flight.

One thing that helps me with airplanes (often at 840 mm) is to keep both eyes open. I do not even necessarily need to consciously see the planes – but generally I find them a lot faster when I keep both eyes open.

I also sometimes keep one eye open so I don’t lose the context. It’s a bit schizophrenic though, with each eye observing a differently magnified version of reality.

how were you able to freeze the motion of the hummingbird at 1/640th? I’ve been shooting as low as 1/2500 and still have issues getting the motion frozen.

Note the wings. The hummer is hovering, so its body is pretty well staying in one place at that shutter speed; the wings, beating at 80 / sec, are blurred.

Hummingbirds hover. So, when the bird is moving slowly, you don’t need a fast shutter speed. 1/640 is plenty to get sharp feather detail when it’s hovering. Only the wings will be blurred, which is usually not a problem as it looks good. You have to wait and take the shot when the bird is hovering near the flower or plant.

It is as Michael and Jason write. Although hummingbirds are extremely agile creatures, their bodies can be almost motionless for a brief moment while feeding at a flower. I’ve tested much longer shutter speeds and I’ve gotten to acceptable sharpness with shutter speeds around 1/125s. Of course, the wings are a problem. The ideal is to choose a photo from a series where the hummingbird has wings in front of or behind its body. In these positions, the relative angular velocity to the camera is lowest and the wings are acceptably sharp.

For bird photography, I prefer prime 100%. The reason is that in bird photography, the fine feather detail is important most of the times, and a prime often renders that better. The difference in resolving power between prime in zoom is often not apparent, but it is with fine feather detail, especially at a modest cropping level.

Also, with primes, you absolutely do get less flexibility, at least at first. But personally I like being restricted to a single focal length and just focusing on what I can get with that. That would be a personal preference, but I think it’s worth thinking about.

And finally, the PF primes are light, and much nicer to handhold than the zooms. (The 180-600 is much less comfortable than the 500 or 600PF).

If I could afford one I’d get a prime. I agree that restricting oneself to a focal length really sharpens the brain, the eye, and the imagination. And you get more exercise.

I agree with what Jason writes. I’ll just point out that both Jason and I have a particular fondness for bird photography. That said, the subjects our hearts beat for are pretty similar in size. If one is not so thematically defined and photographs “anything that moves”, the zoom is definitely worth considering. As for the price, zooms are generally cheaper, but used primes can be purchased for a fraction of their original value, which pretty much reduces that difference. The 500mm f/4 telephoto lens I use I bought for $5,000. That’s not exactly cheap, but it’s not as unaffordable as if I were buying it new. Of course, an optically great, feather-light 500mm f/5.6 could be bought considerably cheaper. Essentially for the same money as a new zoom 180-600mm (maybe less).

This^… 100 percent agree!

This is a very interesting subject and one I have touched on before about Bokeh and Subject Isolation being an option in a Post Software, where a lesser lens can accurately mimic a more expensive faster lens.

For those who use the following software and run equivalent software types as part of post processing the following is an assured experience to be had.

On the subject of Image Sharpness / Image Quality being created for an image using Post Software.

The image quality enhancing capabilities of Software such as DxO’s PhotoLab and PureRAW , when used to incorporate the addition of the software’s lens and camera models, has been discovered when used to have substantial advantages.

To attempt to prove likewise, it will require a very very adept investigator to discover where discernable image sharpness / image quality difference is to be found between captures from lenses that have a substantial difference in their purchase price. This stands for both Zoom Lenses and Prime Lenses.

Using certain suites of modern software ‘cancels out’ differences such as image sharpness between the Big Price Tag Lens Models and the much more Budget Friendly Lens Models.

The same is also able to claimed for Image Quality as well.

With the above in mind and if one cares to believe this is the result as outcome.

It creates a situation where the features belonging to specific lenses are what is left as the attractor to a Lens Model.

If one wants the most attractive Bokeh and Subject Isolation, this comes with a premium cost and a Lens that has the heaviest weight, especially when the Model is a Telephoto Prime.

The compromise of the Prime Telephoto being, the shortest focus distance is quite extended to other models with a similar Focal Extension Range.

Alternatively for a extended Focal Length is the Zoom Option.

Offering a much increased overall Focusing Distance, where the shortest focusing distance has won over many advocates.

The Compromise being, not the best of the Bokeh that can be produced or not the best for Subject Isolation.

It is this lens type one goes for when lenses are selected for reducing overall equipment weight.

Neither Lens Option as outlined, will sell one short on image sharpness or Image Quality, especially when either lens are having a image processed through a Software as stated that offers Lens / Body Selections.

Captures viewed for differences between images taken at Parity Apertures will be quite indistinguishable.

As a side, I am no longer able to carry equipment as seen in the Trio with Tripods over Shoulder.

Such a overhang of weight from the Bodies ‘centre of gravity’ caused havoc with my aging joints.

The Trek back was sometimes almost abandoned due to Joint Pain.

Today, using my adopted methods, I can carry equipment for a long hike just as precariously, but not be as distressed as part of the experience.

Recently moving over to a 40mm Monopod, improved the mental mindset for the security factor for the equipment substantially.

Compared to 10 or 15 years ago, the great thing is that we have a choice. Zooms today are of such high quality that at first glance few people can really tell the difference in quality between them and expensive primes. The powerful software you mention is also a great help in this regard, as it largely compensates for the weaknesses of zooms such as noise resulting from narrower apertures and lower sharpness. But the same software works equally well on primes, so the relative differences between lenses are not eliminated, only the overall perception of quality is shifted. Finally, even the much praised subject separation capability of fast primes has its limits and as you can learn in Spencer’s latest article, “Bokeh Is Less About Your Lens, More About You.” Still, for some (not 100% rational) reason I enjoy shooting with fixed glass more.