I just got back from a trip to the American Southwest where I photographed landscapes, the Milky Way, and a rare annular (“ring of fire”) solar eclipse. My bag was filled with lenses that I’ll be reviewing imminently – some from Nikon, of course, along with a few Canons and Sonys. That’s right, we can finally test Canon and Sony lenses in the Photography Life lab, which has been years in the making! But more on that later. Today, I want to share some details about the eclipse and the photos that resulted from it.

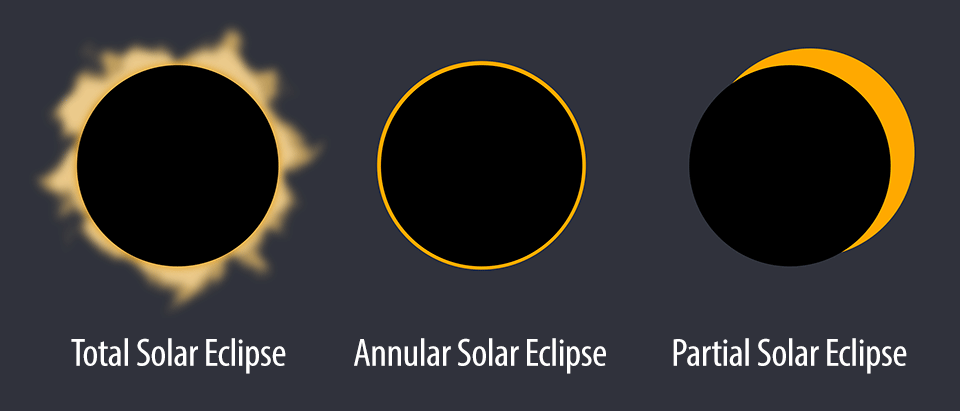

For context, the eclipse this time was an annular eclipse rather than a total eclipse. Because the moon is currently farther away from Earth, it can’t quite fully cover the sun. This leaves a ring of the sun visible around the edge of the moon. (It also meant that I couldn’t look at this eclipse without wearing eclipse glasses, unlike with a total solar eclipse, where you can look at it with the naked eye during the few minutes of totality.)

On the day of the eclipse, I was leading a workshop based out of Sedona, Arizona with my friend Steve Gottlieb. Sedona is a few hours’ drive from the epicenter of the eclipse, so we woke up early on October 14th and drove north to the town of Kayenta. There are some beautiful rock formations around Kayenta, allowing for the possibility of wide-angle photos that capture the landscape with the rare rare celestial phenomenon overhead. Luckily, we had clear skies and got to see the eclipse in all its glory, both with a supertelephoto and with a wide angle. I still need to process my film photos from the eclipse; the photos shown below belong to Steve, and they give you a great sense of what the eclipse was like from the ground.

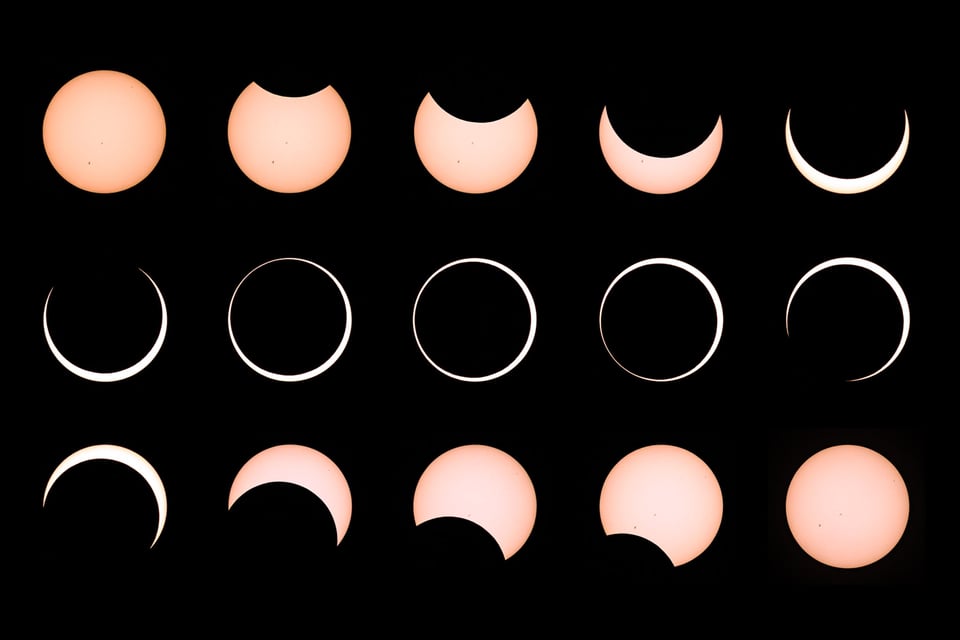

The full progression of the eclipse took about three hours. Shown below is a 15 image composite showing each major stage of the eclipse, taken at 800mm and using a solar filter on the front of the lens to avoid burning a hole in the camera sensor. What may look like specks of dust on the sun are actually sunspots!

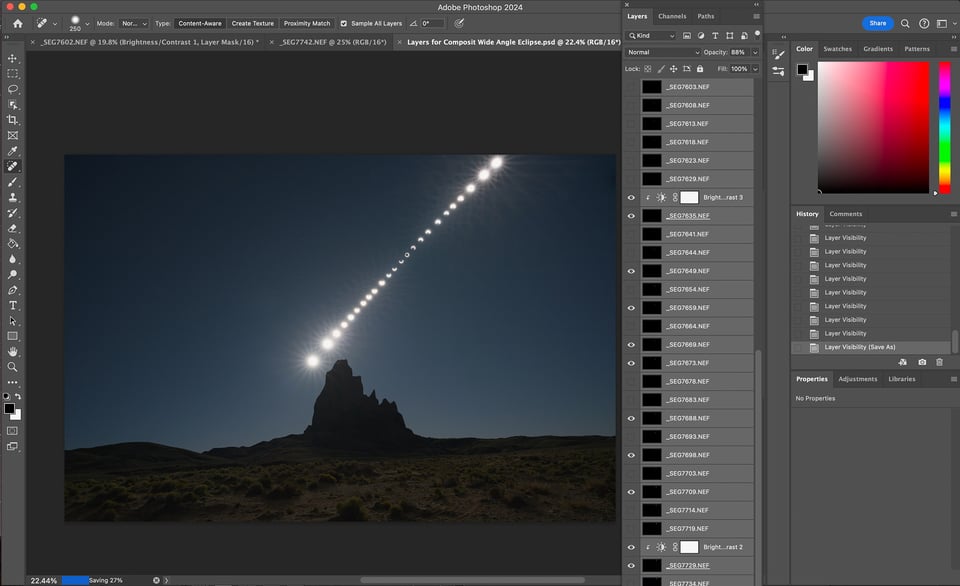

For the second type of photo, our goal was to capture a wide-angle composite to show the path of the eclipse across the sky, relative to the landscape. I knew this was going to be a much more difficult photo because of the difficulty of exposure. Exposing for the sun meant a pitch-black landscape; exposing for the landscape meant a massive, blown-out sun (even during the moment of totality).

It was a bit of a juggling act, but we settled on primarily exposing for the sun in order to show the progression of the eclipse as clearly as possible. I thought we might need to take a separate photo of the landscape later and then merge it into the right place at the bottom of the photo. This, however, turned out to be unnecessary! All I had to do was open each photo as a separate layer in Photoshop, set the blend mode of each layer (except the one at the bottom) to Screen, and then watch the composite appear before our eyes with a well-exposed foreground and a small, detailed sun.

Only minimal Photoshop work was needed after that point. Since there were about 70 photos spaced at different intervals, we manually hid or enabled layers in order to get a pleasing spacing between each of the suns. In the layers that remained, minor brightness adjustments were sometimes necessary (either up or down) in order to make that particular sun the correct size relative to the ones around it. Then the composite was complete, and the few remaining adjustments could be done in Lightroom.

I had expected it to be a complex compositing job that would take hours of work, but it took hardly any time at all. Whenever I next photograph a solar eclipse, I’m definitely going to follow this same method. Here’s the result.

Although the next annular solar eclipse over the United States won’t happen until 2039, there are other annular eclipses before then in different areas of the world. (Here’s a list of annular + total eclipses through 2029.)

Those of us in the USA still have plenty to look forward to, however, since there’s a total eclipse on April 8, 2024 that stretches all the way from Texas to Maine. It also covers parts of Mexico and Canada. Total eclipses are arguably even more exciting than annular eclipses – you see the sun’s corona, the sky darkens more, and you can view the totality without solar glasses for a few minutes. Do some research, and you may find that you live near an upcoming eclipse!

It goes to show that even in the slow-paced genre of landscape photography, where many of our subjects will look similar a thousand years from now, there are still fleeting moments to be captured. Careful planning, good timing, and a bit of luck can go a long way toward capturing these subjects, not to mention just seeing and experiencing them in the first place.

Well done Spencer. I dreamed about something like this at the Albuquerque balloon festival but the traffic drove me away up to Sandia peak. From there I just enjoyed the experience with my family. I need to study up for the April eclipse.

Very nice! Definitely looks more realistic than most composite attempts. For the composite landscape did you shoot with a filter at all?

The peak there in the photo is Agathla. Another volcanic plug similar to Shiprock further east in NM.

I got some super telephoto shots myself from around the Halls Crossing area and then fought thru eclipse traffic back home. Still need to composite them. I think that McDonald’s in Kayenta must have had one of its top days of business after the eclipse.

No filters for the wide composite. There was a lens cap on the lens most of the time, which we briefly removed for each shot. I wasn’t too concerned about sensor damage at such a wide angle and such short times.

And I was one of those people at the Kayenta McDonald’s afterwards!

The problem with a wide angle lens is not so much about protecting the sensor, but exposing the Sun correctly. I am afraid most of the “Suns” are overexposed.

Exposure was easily the hardest part of the process. That said, the overexposed sun you’re talking about was an artistic choice to show how the sun dimmed, then brightened again, over the course of the eclipse.

I see. I suspected it was because you did not take a shot of the foreground when the Sun was still out of the picture, and you had to overexpose the “Suns” because of the need to expose the foreground.

We did take some photos without the sun at the end, but they ultimately weren’t needed. This is for the reason you describe – the brighter images at the start and end of the sequence were already enough to illuminate the foreground (which was helped by using the Screen blend mode in Photoshop).

I personally prefer a properly exposed Sun because you get to see more clearly the different “phases” of the Sun with the different shapes of crescents etc. But to each his/her own.

I was doing something similar to you in the backcountry in UT. It took some effort to lug two tripods, two bodies, a zoom lens and a wide angle lens out there! Initially I was inspired by Cripps’ photo (www.nikonusa.com/en/le…esert.html) and was hoping to be able to get a silhouette shot, but quickly realized that the Sun was too high in the sky (20-40 degrees elevation during the eclipse phases) for that to be practical. I settled for getting close up shots of the Sun while using a wide angle for a “string-of-pearls” shot. I used a Nikon Z 100-400 mm lens with 2x TC as you did, but on a Z7II. For the wide angle I used a Canon 24 mm T/S lens on a Sony A7RIVA. I did use a solar filter on the wide angle, and took a background shot without the Sun in the frame.

Solar filters seem to get used only during eclipses and I always wonder at what focal length is it necessary to use one to protect the sensor? Clearly, it is probably necessary at 400 mm and 800 mm, and probably at 200 mm, while on the other hand, it is common to take wide angle shots with small apertures and the Sun in the frame. But what about at focal lengths from 50-200 mm? What is the cut off for a solar filter? Has anyone done the experiment (though it is a potentially expensive one)?

I actually like the “over exposure” here. Makes it look more natural compared to what is normally done. I’m actually surprised you were able to get it like this at all without a filter. I think I tried shooting at low iso, quick shutter, and f45 and couldn’t get any shape to the eclipse. Hence my previous question.

Thanks! Yeah, the darkest in the sequence were at f/22, ISO 64, and about 1/30,000 second on the Z9 if I remember correctly.

Wow. So, this would not have been even possible with a Z7II or an A7RIVA, because the fastest shutter speed available is 1/8000 s! Even the newest A7RV has the same limit. Benefits of the electronic shutter of the Z8/Z9?

Correct, not without using a filter of some kind, at least.

Thank you for a realistic composite. There are so many images being posted with the Sun in the wrong direction, wrong elevation, wrong size compared to the foreground, etc. One of the craziest showed not only the Sun but the fully-visible Moon in each image. Simply not possible.

So, again, thanks for some reality.

Thanks, David – that was the goal! It’s as real as possible, just with more dynamic range than our eyes can see.

Spencer

Like the explanation how how to blend the pictures together.

Did you shot in the location you were planning on originally?

Thank you! Yes, more or less. There were a few alternative locations I had in mind, and we considered Monument Valley itself until they announced it would be closed during the eclipse, but this turned out to be a great spot with minimal crowds. It’s called Agathla Peak.