If someone is very familiar with your style of photography, it’s not outlandish to think that they could pick out one of your photos in a crowd — even if, for example, you’re a macro photographer, and the crowd includes nothing but macro photos. I’ll frequently see a shot on Instagram or 500px and recognize who took it, even before I see their name appear; that’s the power of personal style. At the same time, when I try to do this, I’m often wrong. It seems that certain “styles” are adopted by more than just one photographer, often very convincingly. In this section, I’ll try to pinpoint the ways in which someone’s style can arise, as well as the problems with replicating another photographer’s personal style.

3) A Case Study

Last time, I listed five elements that combine to form a photographer’s personal style:

- Subject Matter

- Color palette (or tonality)

- Quality of light

- Composition

- Camera settings and equipment

As I mentioned, though, personal style is made up of much more than just this. Let’s take a look at an example where these five elements may not be enough to define a photographer’s style convincingly.

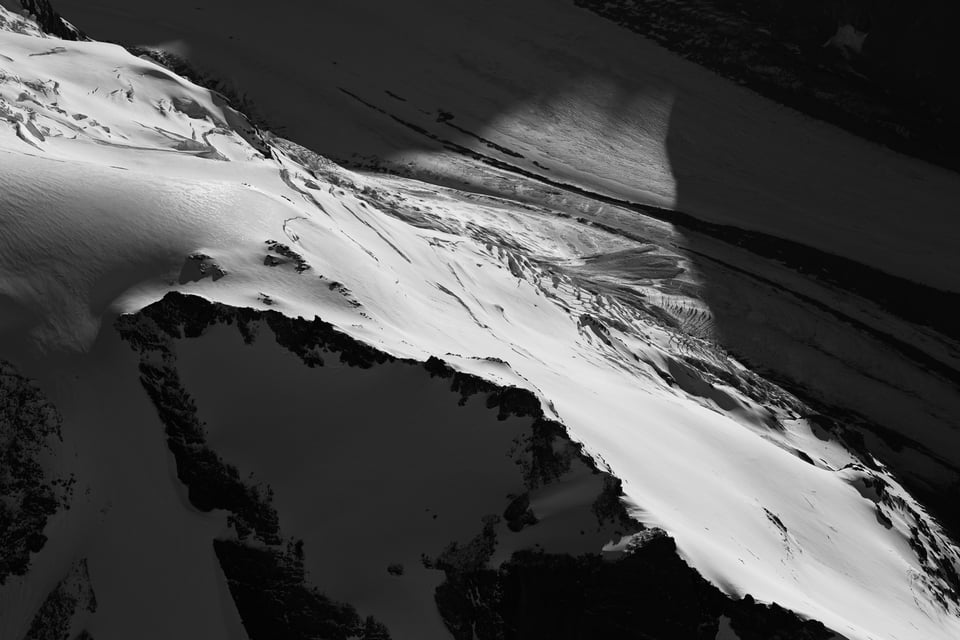

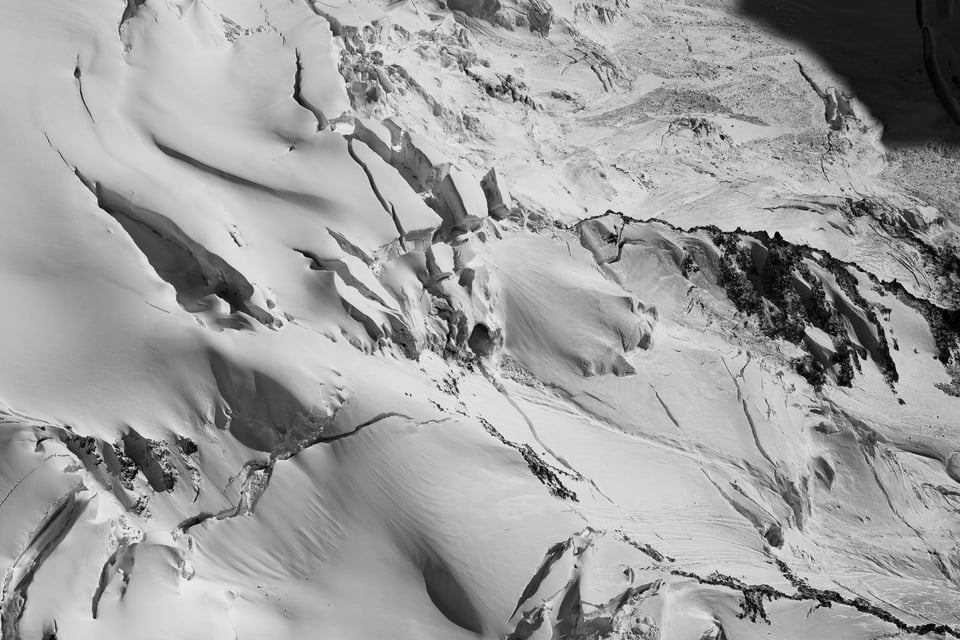

It involves the photographer Lewis Baltz, who, mainly during the 1970s and 80s, photographed semi-abstract photos of buildings in black and white. Here’s a list, following these same five elements, that attempts to pinpoint his style:

- Subject Matter: Outdoor walls of concrete, industrial buildings; often run-down or unkempt

- Color palette (or tonality): Black and white photos, with a relatively high degree of contrast and deep shadows, but a bit of a “faded” look

- Quality of light: Relatively soft light, without harsh edges or bright, specular highlights, though sometimes shot at midday

- Composition: Head-on, at eye level, flat, balanced, often symmetrical compositions, with strong geometric shapes and straight lines

- Camera settings and equipment: No dramatic perspectives (i.e., ultra-wide or supertelephoto); medium lens; sharp photos; taken with black and white film.

Does this sound like enough information to pinpoint Baltz’s work?

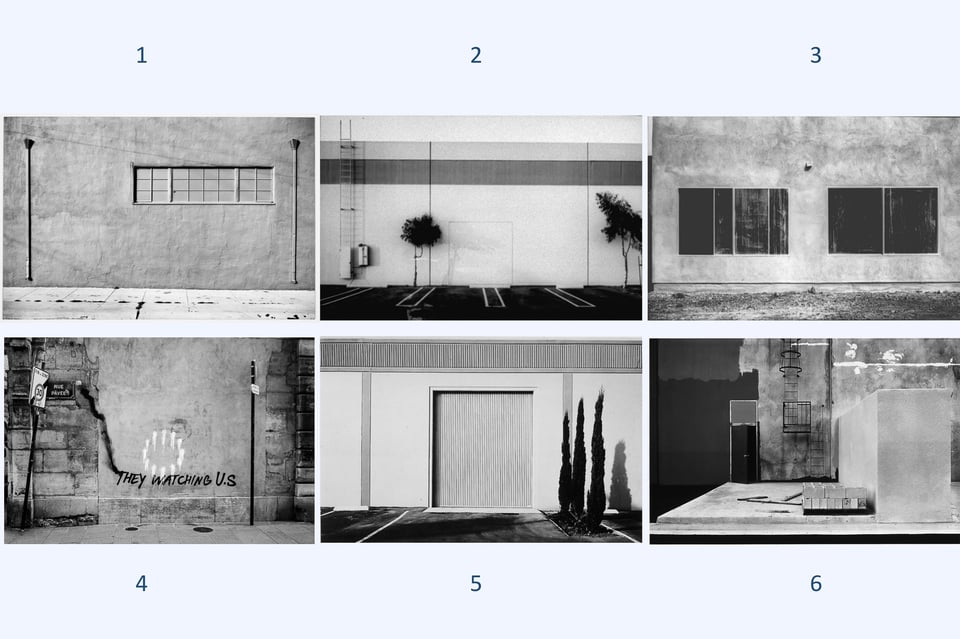

It’s not a trick question, and the demonstration below — with five photos taken by Baltz, and one that wasn’t — isn’t meant as a trick, either. Instead, it’s intended to demonstrate the extreme subtlety of personal style. Even though all five of these attributes remain relatively constant across all six photos below (except that the one outlier was captured digitally rather than on film), most people are able to tell which image does not belong in the set below. If you want to guess, don’t scroll to the paragraph after this comparison until you’re ready:

These photos are clearly quite similar; they all have shared elements and features. However, many people can see that the fourth photograph is a bit different from the others, even if it may be difficult to define exactly why.

Indeed, that is the one that Baltz did not take.

Does the fourth photo stand out due to its range of tones and contrast, which seem to be a bit different from some of the others? Is the graffiti on the side of the wall— an element unique to that image — to blame? Or, are the real differences more subtle?

Other viewers may not have realized that the fourth photo is by a different photographer, which is an equally interesting outcome. That shows it is possible to imitate the style of another photographer simply by copying some fundamental elements — subject matter, composition, and so on — that the photographer tends to use.

This brings up an important point: There are two separate ways to take photos that have a well-defined style. The first is to follow, essentially, a checklist, methodically making sure that every aspect of your photo fits into a particular mold. The other is more spontaneous, where your personal style emerges from the photos that you naturally happen to take. This is the difference between method and personality. Both have a place in today’s world of photography.

4) Method Versus Personality

If you want your photos to have a clearer personal style, and you don’t think that your portfolio looks interconnected enough as it is, it can be encouraging to know that a five-item checklist will get you pretty far. Personal style is a nebulous concept, and a few concrete steps make it much easier to put things into practice.

At the same time, this leads to a disconcerting possibility: With a good enough checklist in hand, other people can copy an artist’s personal style robotically, thoughtlessly, and convincingly.

Without a doubt, this is something that happens in the art world. Even outside of photography, there are several examples of personal style that have been copied convincingly in the form of forgeries. To name just one example, Otto Wacker — one of history’s most infamous Van Gogh forgers — created imitations that were convincing enough to fool a contemporary computer analysis of his brushstrokes. That’s pretty disconcerting.

Many people will take issue with the fact that an artist like van Gogh can have his work imitated so well that even a computer can be fooled (as well as, for many years, art historians). If van Gogh’s art is so spectacular, does that mean that forgers who recreate his personal style convincingly are equally great artists?

To me, this question hits at the heart of personal style, which is summed up well by poet Frank O’Hara:

“Style at its lowest ebb is method. Style at its highest ebb is personality.”

Yes, at times, it is possible to copy someone’s personal style convincingly. That rarely occurs naturally, though, or by happenstance. Instead, realistic forgeries — particularly in arts like painting, but also in photography — tend to be very deliberate, even more so than the original work. By copying the exact method that an artist uses, carefully running through a checklist of elements to include along the way, it is possible to create a realistic imitation. But that doesn’t mean that the initiation is inherently as successful as the original.

However, I mentioned above that there is still a place for the “method” method in photography today, and I do believe that is true. When is it a good idea to follow a checklist while you’re taking pictures?

As one example, I would argue that corporate photographers — those commissioned by large brands like Nike or REI — often need to follow the “method” method of personal style simply to produce work that the company requests. That’s because the brands themselves have a personal style to convey in their advertisements, and, to some degree, the photographer must be able to match that aesthetic in order to get the job done.

The same can be said of a photographer whose primary goal is to capture high-popularity photos, or work that appeals to a particular audience. If the public is interested in vivid photos of dramatic landscapes at sunset, and they reward such photos with popularity and sales, it’s reasonable to expect photographers to copy that style whenever possible, particularly if their livelihoods depend upon it. This is precisely why the Orton effect has gained so much popularity as a post-processing method these days; it’s just what sells. Good or bad, I believe that it’s justifiable to follow the checklist method if that’s simply how you make a living.

Yet, for many photographers, that’s not the type of photography that appeals to them. Instead, they want their personal style to reflect their personality. As we all know, van Gogh wasn’t universally adored during his lifetime, since he didn’t use his talents to match the prevailing tastes of the public; he just painted how he liked. This is the epitome of the personality method.

Your personality shows through a photograph, ironically, when you don’t really do anything. It’s your default state — the photos that most closely mirror the way you actually see the world.

I’ll dive more into this idea next time, because it’s pretty important. But the takeaway message is that, by default, you’re already shooting with your personal style. Although it’s something you can change, cultivate, and perfect over time, it’s also something that happens, in a broad sense, accidentally.

So, if you’ve never even thought of the “method” of personal style before — meticulously copying a look that you think other people will like — you’re actually pretty far along on the personality method. The two are mutually exclusive.

Hopefully, this section raised some questions about personal style, along with the way you implement it in your own photography.

First, as the Lewis Baltz example demonstrates, personal style is full of subtleties that cannot always be put to words. However, it is also clear that the checklist method has the potential to let you copy someone else’s style convincingly (or let someone else copy yours).

That’s a worrying thought. No matter how much time and work you put into your unique method of photography, someone who is determined will almost always be able to imitate that style. But there’s also a reason why hundreds of millions of people know of Vincent van Gogh, and far, far fewer have heard of Otto Wacker — in the long run, forgeries aren’t worth much of anything.

In the final section of this article, I’ll go into the positives and negatives associated with developing your own personal style, along with the risks of over-analyzing your work. Personal style can seem like an imprecise, abstract concept, but it’s also the best way to get your work to reflect your unique vision of the world. In that sense, it’s one of the most important topics in photography.

Table of Contents