In the fourth of a series of follow-up articles to The Quality of Light, I will describe my interpretation of the intersection of light and aesthetics in landscape photography as well as the thought process behind the construction of a singular landscape photo. My goal with this essay is to encourage my fellow landscape photographers to be inspired by light in the visualization process.

Last summer, I had re-read Galen Rowell’s landmark publication, Mountain Light: In Search of the Dynamic Landscape, which is arguably one of the most stunning and inspiring treatments of light and landscapes ever produced by a photographer. In one of Rowell’s most compelling chapters of his book, ‘Selective Vision’, he writes reflectively of the photographer’s imperative in translating artistic vision into reality with the goal of creating an emotional connection with the viewer:

When we are deeply moved by a photograph of a landscape, we are usually reacting to what I call the ‘selective vision’ of the photographer rather than to the fidelity of the scene itself.

Photography succeeds not when the original vision is created photographically, but when the photo is able to evoke or re-create a similar vision in the mind of each viewer. If the re-creation is not understood or not relevant or not powerful enough, the image fails. But if the special unity of composition found by the photographer triggers strong emotions, the image has a chance of success.

Rowell’s message to the landscape photographer is powerful. He advances that the goal of the landscape photograph should be to transcend a mere reproduction of the physical world as seen through the camera lens in order to create emotional impact that resonates with the viewer. Without a doubt, this artistic imperative in landscape photography is the epitome of the visualization process, yet it is a challenging imperative to execute. Whether the landscape photographer succeeds with this undertaking will be predicated on his or her artistic vision, his interpretation and manipulation of the light, and skill.

Let’s consider the following photograph that I had made this past winter at Death Valley National Park. Once again inspired by light, structure, and mood, I set out to construct a landscape photograph with Rowell’s philosophy at the forefront in my visualization process. How could I create a landscape image that transcends a replication of the physical world so as to create emotional impact with my viewer?

Tachihara 8×10, Caltar II-N 240mm f/5.6, Kodak Ektar 100, Hoya 81A

To this end, I desired to create an uplifting mood that would be imparted by the warmth and vibrance of the ‘Golden Hour’. In my prior landscape photo shoots, I had made generous use of this quality of light – unfortunately not always with the best results in creating emotional impact. My goal with this photo was to create an image where my viewers would vicariously experience the vibrance of this magical light as it instilled vitality into a desert landscape. If there was somehow a way where I could make my viewers feel the same vibrant glow of light on my visage as I stood behind the camera, then I could potentially accomplish my artistic objective.

I chose one of my preferred qualities of light – oblique lighting (a combination of backlighting and side lighting). As I had previously discussed in A Study in Light, Shadows, and Landscapes (SLSL), oblique lighting is an instrumental tool to reveal textures, define shape, and create a sense of depth in a landscape. To create the aesthetic effect for which I was seeking, I took advantage of the backlighting component of this light. Although many landscape photographers make concerted efforts to avoid introducing flare into their photos (myself included) for good reason, in this particular photo I deliberately sought to introduce a limited amount of flare into this photo. Why?? Because I wanted to accentuate the emotion of the early morning sun bathing the landscape on a cold winter day in the desert, I visualized the modest appearance of flare as potentially imparting an aesthetic quality to the landscape and evoking an uplifting emotion.

As I deliberated where to place highlights in the frame, I wished to avoid placing them (and thus any flare) in the upper middle of the frame because that would have been too distracting. Thus, I chose to make the exposure with the axis of the lens facing the landscape such that the incident lighting would emerge at an oblique angle from the upper corner of the frame. As I had discussed in SLSL, one of the pitfalls of employing strong high values in a compositionally empty part of the frame is that it may distract the viewer’s eyes from the subject of interest in the landscape. In order to balance the strong highlights in the sky, I needed to create structural compositional interest in the foreground that was likewise strongly illuminated in terms of intensity and breadth, especially since I had chosen a wide angle lens – in this case a field of view that is similar to that conferred by a 32 mm focal length in the 35 mm format.

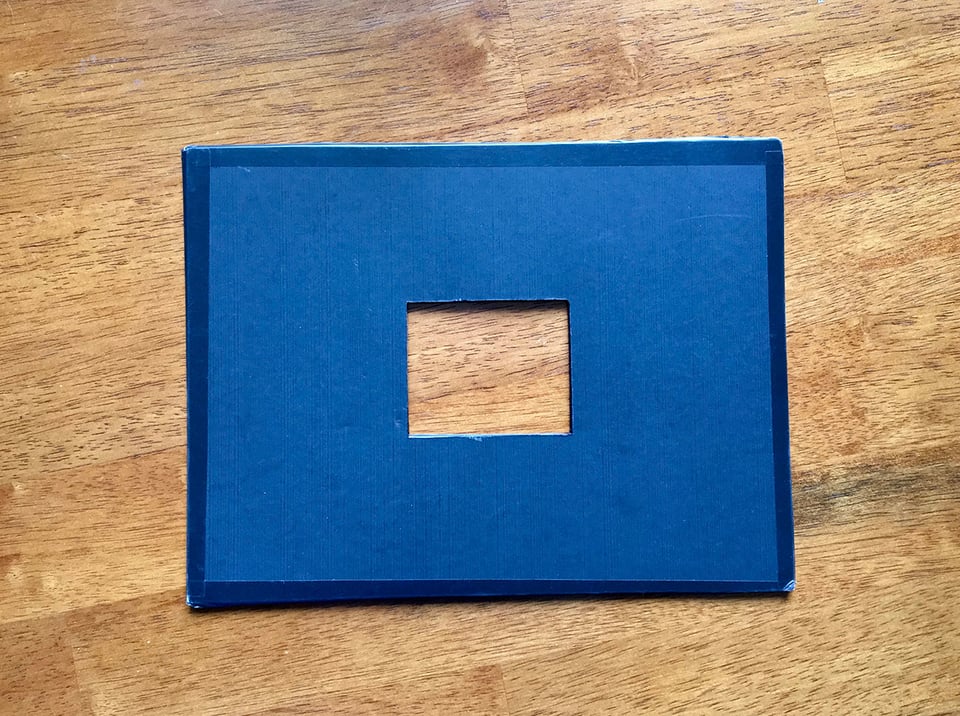

The day before making the decisive exposure, I had studied the scene through my composing card on a scouting trip. Following diligent study of the landscape, the structure of interest in the immediate foreground that I felt could balance the strong high values in the sky were the curved portions of badland rocks.

Due to the coarse nature of these foreground rocks and the oblique quality of light that I had envisioned, I felt that the strongly illuminated foreground and its associated textures would successfully “counterbalance” the strong high values and flare in the upper left corner of the frame and draw the viewer’s eyes into the heart of the landscape.

Further, after I had determined the initial composition it was evident that a portion of the highway would have been included in the frame. Typically, I do not include streets, roads, or any manmade structure in my landscape photos; however, in this photo the inclusion of the road in the frame resonated with me and would serve two purposes. First, the road would have imparted a modest degree of scale to the grandeur of the badland landscape. Secondly, from an aesthetic standpoint the road may potentially confer an urban ambiance to the landscape that may also resonate with the viewer.

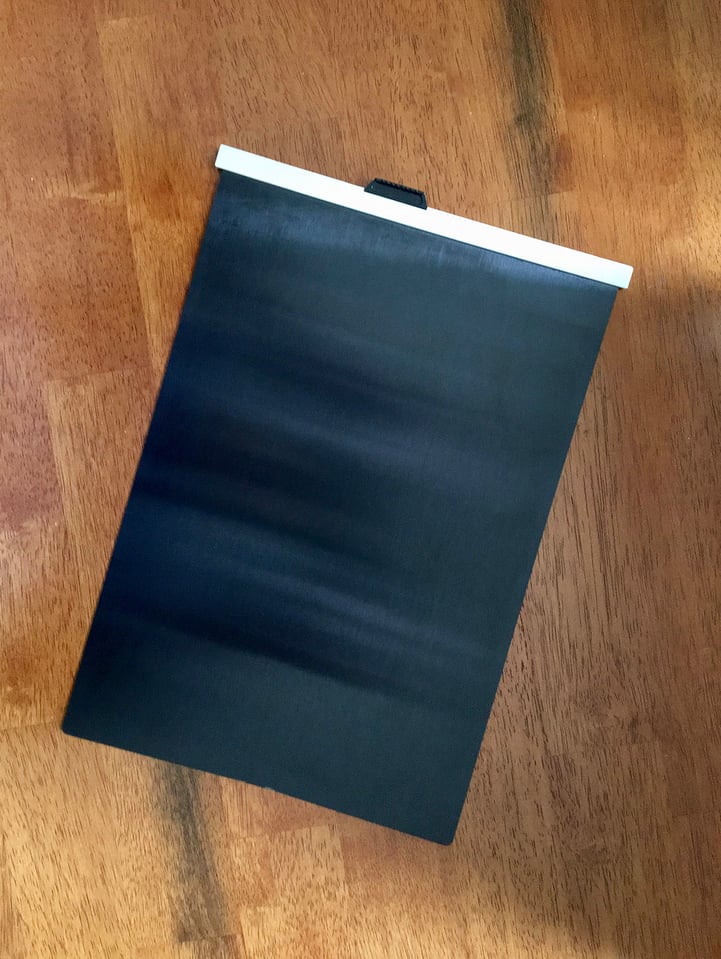

Another technical note: to help moderate the amount of flare during the exposure, I used the dark slide of the 8×10 film holder as a mechanical shield. Perched atop a short step stool to the left of the camera, I held out the dark slide with my outstretched arm in front and above the axis of the lens to shield extraneous light (especially light not forming the image circle) from entering the lens.

After I made the exposure and the time had arrived for studying the final product, I was pleased with the result. At the upper left of the frame, the viewer’s eyes are immediately met by the warm brilliance of the rising sun accompanied by reduced local contrast in that area of the frame by virtue of the veiling flare (not unlike what the human eyes would see).

In the immediate foreground, the strong high values in the landscape are nicely complimented by the strong high values in the sky. This is where the oblique quality of light delivered the goods. In the immediate foreground the viewer’s eyes meet a striking array of coarse textures and strong local contrast – made possible by alternating highlights and shadows that rake across the frame at an angle headed toward to the axis of the lens. Then the eyes are led into the heart of the landscape where a series of less prominent highlights that alternate with deep shadows lends a sense of depth and mystery to the frond-like ridges of the badlands as the eyes are enticed to explore the mountains in the distance. Hopefully, if the light, texture, structure, and depth were visually and emotionally impactful, then the viewer would be inspired to repeat the experience by re-engaging the strong highlights in the sky.

As I view this image, I genuinely feel as if I am standing right in front of this majestic landscape all over again to relive the experience. From an aesthetic perspective, I can see and feel the warm glow of the rising sun bathe my face and cause my eyes to squint as I witness the beauty unfolding in the landscape. The veiling flare that I had purposefully introduced enriched the aesthetic feel of this image. Whether I was successful in evoking the same emotion in my viewers remains to be determined; but I believe that the alternative approach that I used in the construction of this landscape photo was faithful to my own visualization process. It was an enjoyable and memorable experience.

One final technical note: the choice of lens is instrumental in moderating the veiling flare and preventing it (and ghosting flare) from sabotaging the exposure. In addition to mechanically shielding non-image circle forming light from entering the lens (e.g., use of a dark slide, a lens hood, your hands, a hat, whatever), the use of a multicoated lens that possesses relatively few lens elements and a multicoated filter (if applicable) are essential. Modern multicoated lenses and lens filters (e.g., UV, polarizer, black and white contrast filters) are specifically engineered to minimize flare. For example, the Caltar/Rodenstock vintage of large format lenses is legendary for its exemplary multicoated and high contrast glass; its lenses are perpetual outstanding performers. The specific lens that I used to make this photo has a modest number of elements (six in four groups), which also helps to minimize the degree of flare.

Conclusions

In landscape photography, unifying artistic vision with light to create a compelling landscape photo that resonates with your viewers is one of the most challenging, yet enjoyable, aspects of this genre of photography. As the incomparable Galen Rowell once wrote, “Vision is as much the work of the mind as it of the eye.” In the creation of any work of art, the artist has to feel it and believe in it. Ultimately, whether your landscape photo is successful will depend on whether your viewing audience likewise feels it and believes in it. In the construction of this landscape photograph, I chose to manipulate the light in an unorthodox manner and employ a compositional element that I had consciously avoided in my previous work to evoke a certain visual and emotional reaction. The photo was not merely a reproduction of the landscape, but a representation that would hopefully evoke the same visual and emotional response that I had felt at the decisive moment of opening the shutter.

The take home message is simple: please do not hesitate to think outside of the box, or to venture outside your comfort zone, as you explore your own visualization process. The notion of introducing unconventional physical elements into your landscape photos should not deter you from translating your artistic vision into a potentially impactful image. If you are making landscapes photos like everyone else, then you are not making landscape photos, and you may not be fulfilling your artistic potential. The light and the landscape are out there waiting for you.

Once again, I extend my thanks to Northcoast Photographic Services for the film development services for this photograph. Great job, Bonnie & Scott!

All of these photographs are copyright protected. All rights reserved, Rick Keller © 2018. You may not copy, download, save, or reproduce these images without the expressed written consent of Rick Keller.

Suggested Reading

- Mountain Light: In Search of the Dynamic Landscape, Galen Rowell.

- Light for Visual Artists, Richard Yot.

- A Study in Light, Shadows, and Landscapes

- The Quality of Light

- What is Ghosting and Flare?, Nasim Mansurov.

Thanks for the series Rick, I really enjoy them. Please keep on posting more content like this!

I Like both these photos. In both, however, the predominant foreground takes away from the visual impact and mood that was desired. Mind you, cropping 25% off the bottom should bring back that objective.

JPH

Rick, thank you for sharing the wonderful images. I tend to agree with Mark’s comment. Lighting is everything. The “scout” image has a stronger overall composition in which one’s eyes trace the foreground toward the eroded sandstone in the midground, then the mountain range and horizon in the background. This leaves the viewers to see that the unique and barren landscape of Death Valley is created by the nature elements. The same message is conveyed in the other “intent” image through the detail foreground, but my eyes do not go from the front to the back. Both images are wonderful but different.

I have visited Death Valley NP several times and always come away with refreshing experience. In digital age the element of nature lighting can be explored more readily and made the appropriate adjustment while in the field. Often I come back to the same location throughout the day just to get the right lighting. Sometime it works and sometime it doesn’t.

In the book, “Mountains of the Middle Kingdom: Exploring the High Peaks of China and Tibet” by Galen Rowell, the cover image was captured as he saw the rainbow moving toward the monastery. He dropped the 50 lbs pack, grabbed his camera, and ran several hundred feet as the rainbow reached the monastery. He made 6-10 frames and rainbow moved past the monastery. I stopped by his gallery in Bishop, CA every time I am near the area.

>>”If you are making landscapes photos like everyone else, then you are not making landscape photos, and you may not be fulfilling your artistic potential.”

I agree, This goes in to originality v/s popularity. Viewers are conditioned to LIKE the photographs with certain angle/bokeh/tone etc. If your photo is not meeting those rules, then they may not up-vote it :). So originality is risky. My approach is, first do not think of what viewers are going to think :). Do not try to take impact-full picture, instead try to take original picture. This may not be a wise approach if photography is your livelihood :). Even in that case one can have pro-work collection that is more stereo typical and personal-work that exhibits unique characters.

A very thoughtful article–thank you. In our digital age of canned effects filters and HDR, I particularly appreciate your comment, “If you are making landscapes photos like everyone else, then you are not making landscape photos”.

For me, both images of Death Valley National Park have particular strengths: while the finished photograph conveys early morning light beautifully, I prefer the balanced composition of the scout image, with the fissured hills leading one’s eye toward the horizon. By contrast, the foreground slope in the finished image, lovely though it is, is nearly overwhelming the most subtle part of the image behind.

I ‘d like to send you an example of a landscape I made which reflects your intent – creating an impression of a subject, not just a depiction of it, but there’s no way to attach a photo in this format. I made it shooting an early morning landscape, shot directly into the sun, with no visible flare. My guess is that modern lenses have good coatings that really work. I used a Nikon D610 and a Tamron 24 – 70 f/2.8 zoom. The result is a beautiful and light-filled image of early morning.

Hi Dan, thanks for your comment. I would be delighted to view your early morning landscape photo. It sounds like it was a glorious experience for you. I’d recommend that you post your photo in our Photography Life ‘Landscape’ Forum by using the forum link in the menu atop this page. Once posted, I would be happy to study your impression and interpretation of your subject. :)

Made it on my second attempt! Thanks for the easy directions Rick.