Today’s noise reduction software is capable of incredible results. Images that couldn’t be salvaged in the past can be made quite clean with modern denoise algorithms. But what is the real benefit of these tools compared to capturing more light in the first place?

Today, I’ll answer that question numerically by measuring the performance of some different noise reduction algorithms versus capturing more light. I’m going to focus especially on DxO’s PureRaw 4 software (reviewed here on Photography Life) both because of its popularity and because of its high performance. I’ve also tested more conventional noise reduction algorithms that don’t rely on machine learning.

Modern Noise Reduction Performance

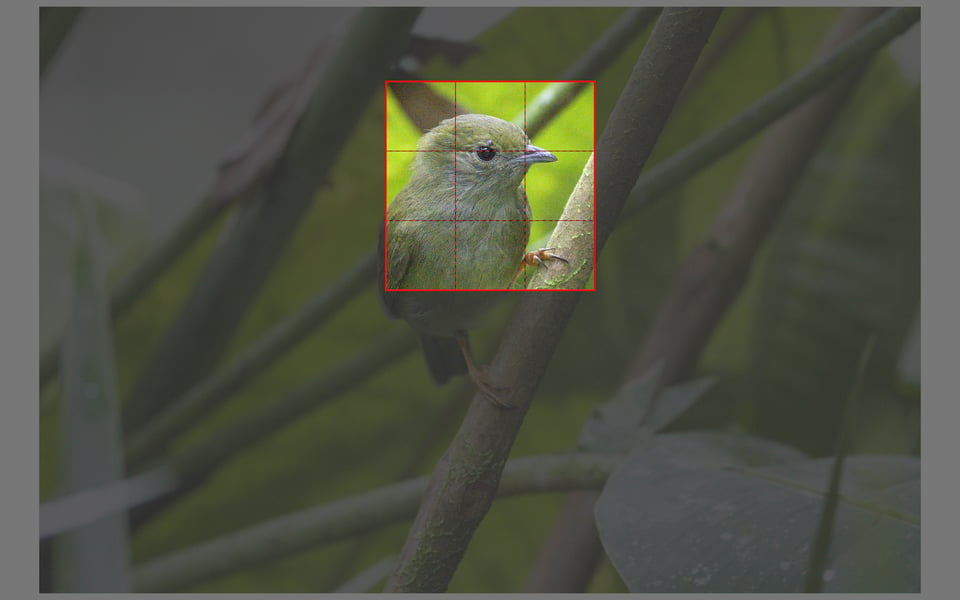

Let’s look at an example of an image with excess noise – a reject photo taken at 20,000 ISO on my Nikon D500:

Whoa, noisy! Above, I’ve indicated the crop I’ll be using to show you what it looks like up close.

Frankly, without any denoising, the result is horrific. I tried denoising it using a non-machine-learning algorithm in Rawtherapee, and also with the machine learning algorithm in DxO PureRaw 4:

I think the results speak for themselves. Traditional noise reduction algorithms don’t perform as well as today’s machine learning algorithms, like those used by DxO, Topaz, and now even Adobe. That said, you still don’t get perfect quality in the processed image because of the high levels of noise in the original.

Noise Reduction, or Capturing More Light?

What I rarely see in such tests is a comparison to capturing more light in the field. How do today’s algorithms compare to simply gathering more light?

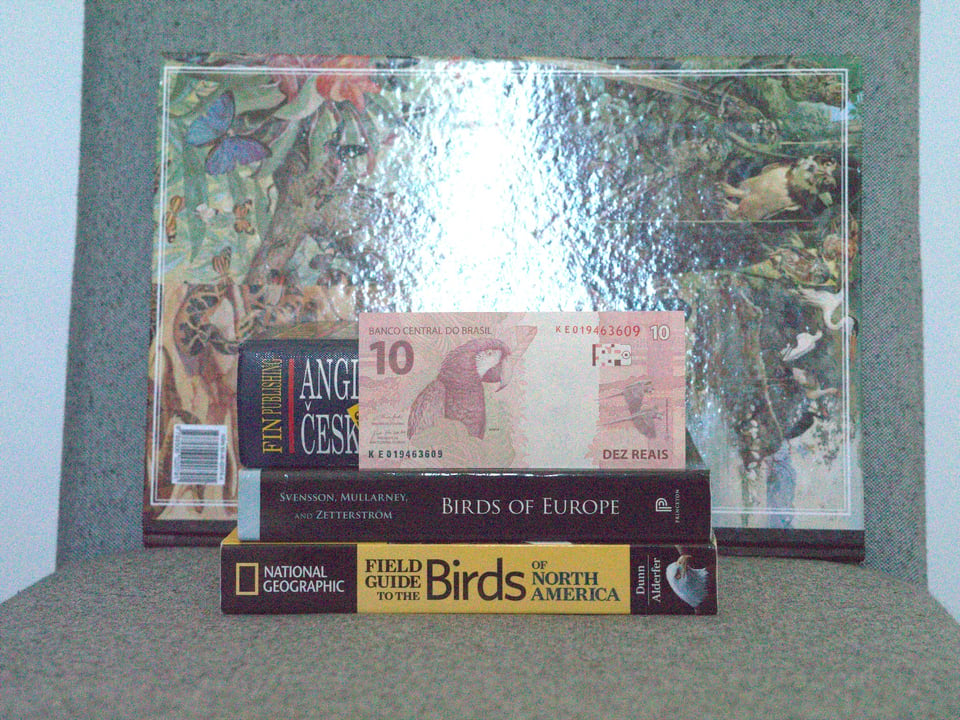

In other words, if I could have taken the exact same shot but with twice or even four times longer a shutter speed, how would the best noise reduction algorithms compare? We’ve all heard it said that “ISO 6400 is like ISO 800 now” and various claims like that. Well, I’ve done just such a test by using a sturdy tripod, a cable release, and a test subject of a bill of money:

To really see the effects of the noise reduction algorithms, I have used a tight crop:

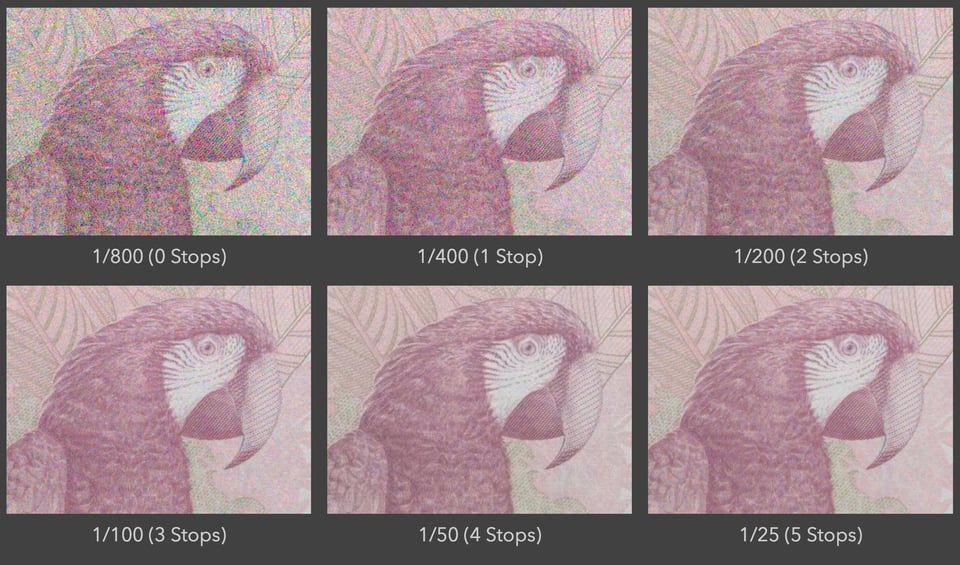

I took successive photos of this scene at shutter speeds of 1/800, 1/400, 1/200, 1/100, 1/50, and 1/25 second. This resulted in capturing one additional stop of light each time. Correspondingly, I lowered my ISO each time. Here are the results:

In terms of recovering detail and image quality, where do modern noise reduction algorithms stand in the list? To measure this, we need an objective, mathematical standard of measuring image similarity.

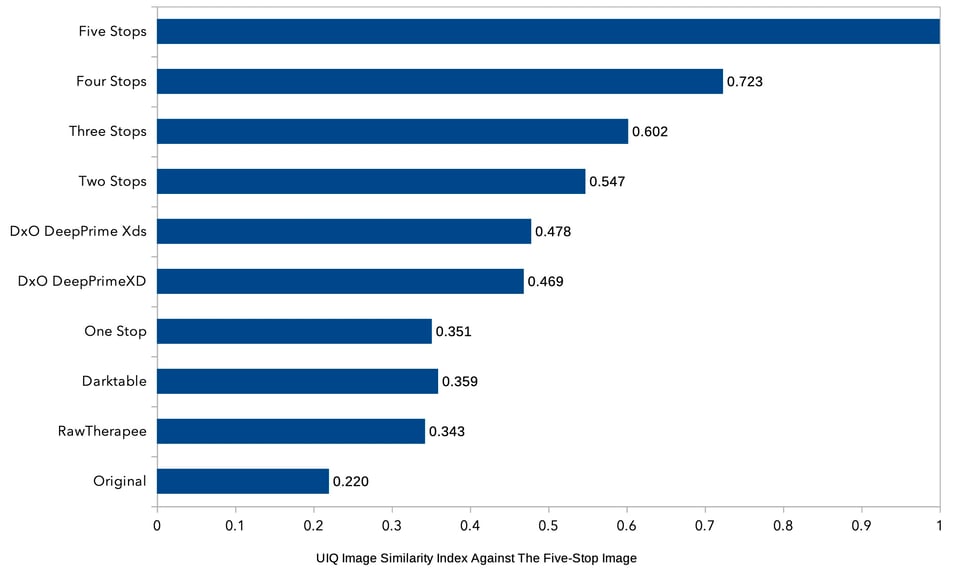

There are many algorithms to measure deviation from an ideal or “ground truth” image. After testing a half-dozen image similarity measures, I found one that was very good at measuring image quality loss due to noise: the so-called UIQ or “Universal Image Quality Index.”

According to Zhou Wang and Alan C. Bovik, who published this algorithm in 2002, it measures a “loss of correlation, luminance distortion, and contrast distortion”, which as I found out, roughly corresponds to the presence and perception of detail.

I used this UIQ algorithm to measure the noise in a variety of images – some with noise reduction applied, some simply taken with more light/a lower ISO in the first place. How many stops are you effectively gaining with today’s best noise reduction? These are the results:

A score of one is a perfect score. The image labeled “original” is the one taken at ISO 6400 and 1/800 second with no noise reduction applied. My ideal image is the one taken at 1/25 second and base ISO 200, which is five stops more light than the original photo. (I’ve labeled this “five stops” in the graphic above, and by definition, it gets a perfect score of 1.)

You can see that in this comparison, there is no doubt – a machine learning noise reduction algorithm like those found in DxO PureRaw 4 are a clear step up over traditional noise reduction algorithms. Such traditional algorithms score similarly to a one-stop improvement, whereas DxO PureRaw 4 is somewhere between one and two stops.

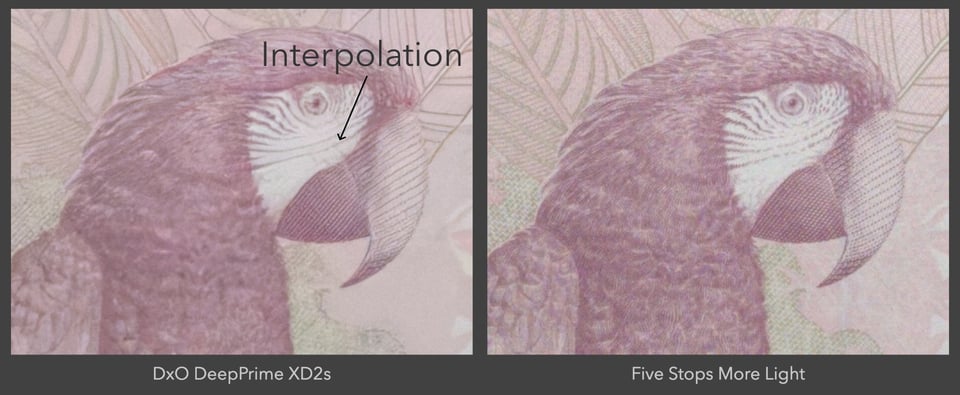

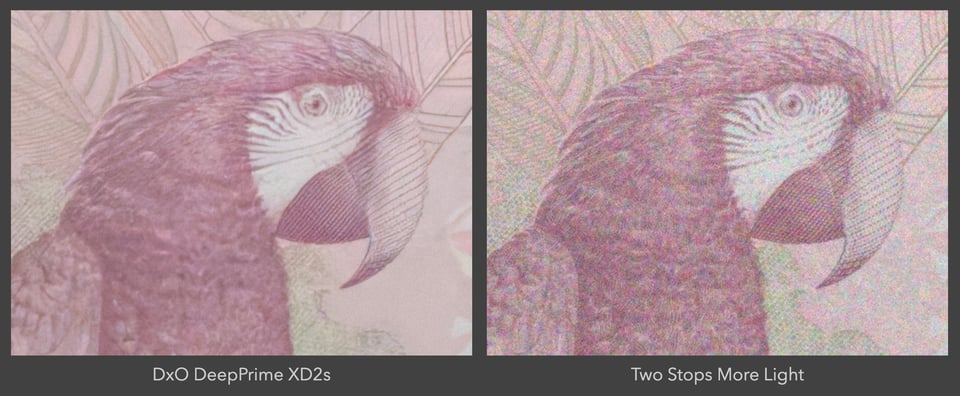

Here’s how this looks in an example image, compared to the photo taken at ISO 1600 (two stops better than the original ISO 6400 shot):

Here, you can see that DxO’s result looks great. There isn’t much obvious noise. However, there also is less detail – the image with two more stops of light clearly has finer details on the parrot’s face. This is why the UIQ index scores the two photos about the same – and if anything, gives the edge to the photo with two more stops of light.

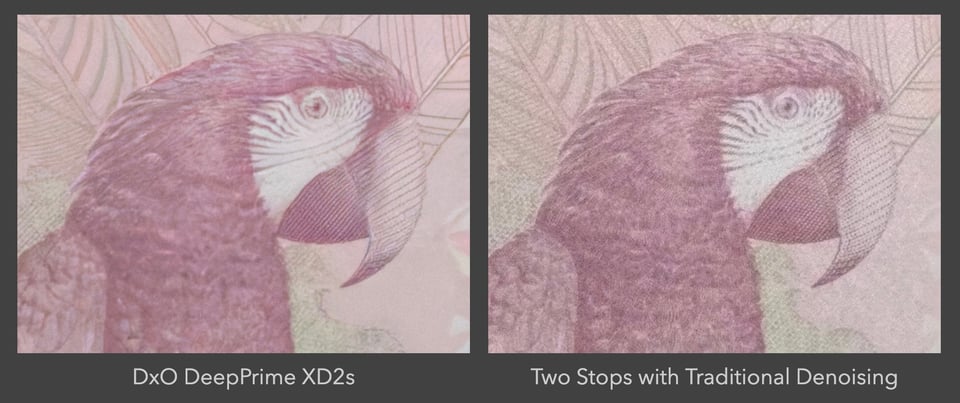

I’d also like to show a comparison against traditional noise reduction, such as the one found in Rawtherapee or Darktable:

The DxO image clearly looks better to me. But something else also caught my eye: the dashed lines on the face of the parrot have been transformed by DxO into contiguous lines! This shows that that machine learning algorithms do invent a little detail via interpolation at a micro level. You can see it very clearly in the comparison below (versus the “ideal” image taken at base ISO and 1/25 second):

This shows that in a way, DxO PureRaw 4 and probably other machine-learning denoising algorithms are less like denoisers and more like “re-drawing algorithms.” They use a network trained on millions of images to decide what details to interpolate. By comparison, the traditional denoising algorithm in the previous comparison did not do the same thing.

Discussion

There is no doubt that DxO PureRaw 4’s DeepPrimeXDs algorithm does an outstanding job. It can give you decent images even if you give it noisy slush taken at ISO 20,000, and some photos today are salvageable that weren’t in the past.

At the same time, such algorithms are not a substitute for getting more light – when you can get more light, that is. I don’t buy into the idea that today’s best noise reduction gets you 3, 4, 5, or even more stops of improvement in high-ISO images. Instead, it offers around a two-stop improvement in performance relative to an unedited photo, and about one stop of improvement relative to traditional noise reduction algorithms.

Moreover, DxO PureRaw 4 can add a small amount of interpolation on a fine scale, effectively guessing extremely fine detail in order to achieve results – which is something not everyone is comfortable with, including myself.

Finally, machine-learning denoising makes the most difference in the ISO 6400+ range. Modern sensors do very well at ISO 3200 and below, and noise in such images can be cleaned with a traditional algorithm without major issues. And, in my experience, I find the best images to be taken at these lower ISO values anyway, because the stronger light gives better color and detail.

Therefore, while DxO PureRaw 4 and other machine learning noise reduction can certainly improve noisy images better than traditional algorithms, it still pays to optimize your camera settings if you want the best image quality. It’s better to capture more light than to use software to make up for excessively high ISOs. And no software can make a high-ISO photo look like it was taken at base ISO.

Note: I’d like to thank DxO for providing me with a license to use this software for testing purposes.

Interestingm I haven’t tried this one, my usual go-to for the slight noise reduction and raw processing is Photoworks. Gotta check DxO out as well.

Nice one! How about sharp lens vs sharpening in post? I think that would be quite useful.

Much more difficult to test, because lens resolving power is a continuous variable and then the perceived sharpness depends on the sort of detail you are trying to resolve.

But my opinion is that for birds (what I photograph), the difference between a consumer zoom like the 180-600mm and the primes is significant enough so that sharpening in post isn’t sufficient for all applications. For other applications like portraits, it definitely doesn’t matter that much and lens sharpness is less critical.

Please see my reply to another commentator who asked about sharpening during post-processing:

photographylife.com/revie…ent-311598

TL;DR:

Perceived sharpness is a combination of both resolution and acutance: it is thus a combination of the captured resolution, which cannot be changed in processing, and of acutance, which can be so changed.

— ”Acutance”, Wikipedia

First thanks for the article, a very nice approach. To extend the articles applicability a few minor nitpicks:

1. The proper way would be to have a second 1/25th photo compared to the reference, to see photo to photo variations. I wouldn’t expect a perfect match of 1.

(Technically an average of 10+ photos at each ISO would give much more insight also into the result distribution)

2. What are the results of applying deep prime XD to the one/two/three/four stop results. At which point is the crossover where despite there being no noise difference the score collapses simply due to debayer differences?

3. “Finally, machine-learning denoising makes the most difference in the ISO 6400+ range. Modern sensors do very well at ISO 3200 and below, and noise in such images can be cleaned with a traditional algorithm without major issues. ”

You cannot make such broad statements based on just measuring a M43 sensor.

If photon noise is the major contributor then that would mean ISO 25600+ range for FF and ISO 10000+ range for APS-C

Replies:

(1) Good point. Your method would add additional statistical validity. I’ll work on Version 2 of the test suite with several photos at each stage to account for random error to estimate a distribution.

(2) Another good point. This should also be incorporated into the test suite.

(3) Indeed, my statement was meant to be approximate and not based on the tests. Indeed, a full-frame sensor will perform better, for sure, though I was sort of equating FF and APS-C in my head when it comes to bird photography due to the greater need to crop on FF with the same lens. But good point nonetheless!

I’d like to add my thanks for doing such a great article and my nit to the list to be picked. You chose a pretty low contrast image. In my experience with all the various versions of Prime, it works better on higher contrast images. I feel (yup, feel) that for my purposes (almost never print bigger than 8×10 and don’t care about pixel peeping) I usually get better than two stops.

It may appear better than two stops but there’s a difference between the overall “look” and the actual information retained, both of which are sort of used in the evaluation. But yeah, for “practical purposes” (who needs those, hah), the actual appearance will certainly look like more stops than 1.5 even for the low-contrast image.

Jason, this article explained, providing numbers, for the first time as long as I know, how useful modern software is as a collateral tool for the photographer’s ability. It is unique content worldwide; congrats!

Modern software is not a “save everything from the waste bin” tool but just a way to optimize already good photos. And don’t undervalue the proof that DxOPureRaw and other AI-based software started to “invent things” when pushed!

Targeting large prints more than social sharing, my standard with the current technology is to use up to 3200 ISO, which is fine. 6400 ISO is usable if you pay attention and process carefully. Anything more compromises results more than I like.

It is reflected in my photo library, where, speaking of the last five years, just less than 1% of my photos are over 6400 ISO, and 90% are 1600 ISO or less.

Thank you very much for your comment, Massimo. I appreciate your perspective. Of course, when used lightly, DxO PureRaw should not noticeably invent any detailst that weren’t already there, especially when it comes to viewing an image at typical distances and not zoomed in of course!

I think your strategy is ideal: if you’ve managed 90% of your photos ISO 1600 or less, then anything you do to them will indeed be just a minor optimization rather than a drastic reconstruction. That’s quite impressive!

I managed to achieve that ratio of low vs. high ISO pictures because I fully agree with your article’s bottom line: there is no substitute for more light.

It doesn’t mean I never take photos at high ISO, but I often move them to the waste bin, keeping just a few meaningful.

Moreover, after a few “safe shoots,” I try to lower the ISO, prolonging the shooting time more and more, shooting a few bursts at any step. In most cases, I get a better photo and forget the first “safe shoots.”

I absolutely agree with that! Safe transitioning to lower shutter speeds is a great technique and I use it all the time. It works especially well on mirrorless when you can get REALLY low shutter speeds.

Jason, nice article, I value very much your accurate, math approach to the topic. Thanks a lot. Can you do one more UIQ measures of results done by traditional (non AI) noise reduction re two shots different in one (or two probably) stops due two change of ISO only, please? I mean two shots, which both have correct histogram (no cuts of edges), but one is more on left and other is more to the right. I’m very interested in which case post noise reduction would get best result. At the very end, I’m very interested in how much ISO impacts the capability of traditional noise reduction algorithms.

Do you mean you want to hold shutter speed and aperture constant, and just modify ISO so that one shot is one (or two) stops underexposed?

Yes, that’s correct.

A couple of weeks ago I read a test that compared Lightroom, Topaz and DXO and the preferred product was Lightroom primarily because the other two create things that don’t exist. I don’t have DXO, but I have Topaz and I’d have to agree. Too many artifacts with Topaz, but I will still try it for images where Lightroom is not working on a particular photo, it’s sometimes better and it has manual adjustments that allow me to select what may be a better result.

Most of us have always known that gathering more light is superior. The way I like to think about it is that higher ISOs are the result of the inability to gather more light. Higher ISO just allows us to see the image in our viewfinder, but a shot at 1/100th and f11 will develop the same whether shot at ISO 800 or ISO 3200.

I will be very interested in testing other software, if I can get denoised samples from each. Yeah, it’s also clear that more light is superior. Nothing can beat a low ISO (high amount of light) shot.

Adorei o exemplo com a nota de 10 reais aqui do Brasil.

kkk, sim, foi um nota em perfeitas condições da máquina da caixa electrônico. Gosto da arara também, um exemplo legal quando não posso encontrar pássaros actuaís.

Cool to see hard numbers on this issue! The results make you seem less stupid for carrying around heavy FF-equipment in the age of great M43 cameras with compact and lightweight lenses. ;)

I have to agree with those saying that Lightroom does a better job with noise reduction than other software I know of. It retains a low level of noise (especially when set to lower values) that gives the pictures a more natural look, while doing a great job at retaining detail without obviously “inventing” new stuff. It mostly feels like it keeps the detail I can discern with my eyes and brain while getting rid of most of the noise – and that’s what I think an ideal NR software should do.

That said, I rarely ever use it at very high ISO, so I can’t judge it’s performance with such images. I mostly use it on photos with ISO 1600-6400 when I’m not happy with the results of “traditional” NR. I normally don’t take pictures when ISO values above 6400 are required.

A lot of people have made the same comment about Lightroom and I am very intrigued to test it against DxO!

As for micro four thirds and FF, I shoot with both and I will say that both do very well, but it’s undeniable that FF for SOME applications makes life a lot easier…

I paid for Topaz De-noise A.i. and used that for a year or two. However, I stopped using it once Lightroom added their own “A.i.” de-noise option. The Lightroom noise reduction nowadays is unbeatable. Although I’ll admit I’ve not used all of the alternatives. I’ve used a few, and I find Lightroom to be the best. Fortunately I have a Nikon D6 and Z9, and I mainly use the D6. I’d say the D6 easily has 2/3rd’s of a stop advantage. Though I’d say it’s even more when you consider or compare the colors and details retention.

The Nikon D6 files shot between 6400-12,800 contain less noise and retain colors, contrast and details better than the Z9. As a photojournalist every bit of advantage in low light is of great importance! I’ll never sell my D6. I might eventually sell my Z9, but I’m taking the D6 to the grave. Anyways, I recommend setting the Lightroom Denoise to around 50-55. I’ve experimented a bit and find that range to give the best results. Unless your image was shot at base ISO or lower ISO’s and it doesn’t need much. In that case I’d recommend setting it lower, to maybe 30-35! I don’t use it all of the time and often the JPEG’s straight out of camera are great, especially on the D6.

Last I’ll say your computer or laptop specs really do matter if you’re like me and speed is important. I personally upgraded a year or so ago to an (late 2023) M2 Ultra 16inch MacBook Pro! The difference was immense as far as speed goes. My older desktop with Topaz De-Noise A.i. would take 2-3 minutes per image. Now Lightroom Denoise is complete within a few seconds. Plus Lightroom no longer crashes on me and I’ve had zero issues, unlike before. So if you can afford to upgrade your computer it’s well worth it. You don’t need the latest and greatest either. An older Apple M1 or M2 chipped devise is more than enough.

It’s surprisingly that you even use noise reduction at all if you’re shooting a D6 :)

The dry, numerical comparison between pictures is great, because clean possible personal interpretations. Then is always a matter where the boundary are set (Jason, we already discussed about boundaries between AI and reality).

Personally, I use Adobe denoise, even if I’ve also Topaz available. For me the purpose is to clean noise with the perspective of a 20×30 print. Usually I do it when I shoot above 3200 ISO. If the denoise destroy the picture I’ll throw away it or I’ll keep it with noise (someone call it character).

Unfortunately marketing now use AI as the Holy Grail for everything, not only for photography. But it’s always a mater of quality. Talking with a chatbot is quite often a negative experience, so is the picture of a bird that looks like a watercolor. Matter of taste, or the taste shift generated by mobile phones, that are adjusting colours, noise, exposure to a level that people do not realize that what they’re looking at has nothing to do with what they’ve seen.

And – for the moment – AI denoise will make better an already nice picture, but crap will stay crap. Maybe in future, but we won’t be obliged to use it.

> Maybe in future, but we won’t be obliged to use it.

Thank you for the comment, Mauro. I will add that some technologies become “mandatory” for practical purposes and we are forced to use them, so don’t be so sure that AI won’t be one of them. For example, camera manufacturers in the future may decide to implement subtle AI-processing in their Raw files that cannot be turned off. Some cameras already have a noise processor and bake noise into their Raw files, for example.

Another obvious example of such a technology is the mobile phone. Some banks require a mobile phone now for two factor authentication, and one bank I know requires a smartphone because the only way to manage your money with it is through an app. How can you function in this day and age without a bank account? It’s not easy, and I couldn’t do it. Therefore, I have a smartphone, even though my ideal world would be one where I wouldn’t own one—I don’t like phones. Thus, in this way, some technologies become mandatory and we are pushed hard into using them even if we don’t want to.

That’s in stark contrast with things like a refrigerator. A refrigerator is entirely optional and it’s quite easy to live without one. I know because I spent the past two years living entirely without a refrigerator in my apartment. So we see that we must distinguish between technologies that become mandatory via their integration into essential services in society, and ones that are truly optional because there are other viable alternatives.

And with the speed at which AI is being integrated into modern society, I would not be so sure that its use will always remain optional. It’s already quite hard to avoid AI chatbots as many companies are using them for customer service now, such as Substack.

I see. All good points sadly very true. But technology are like a coin and there’s a good face in most of the cases. Probably (less convinced) is the same for AI. But photos are not vital. When I’ll realize that my photo will be too good because of some AI integrated somewhere I’ll go back to film, even BW.

I thought I was mightly living without almost any social (only LinkedIn) but living without a refrigerator is of another class. Chapeau.

Actually, it’s much easier than I thought! I barely noticed the refrigerator was gone :) (Except on those days where I craved a cold glass of water.)

Last night I tried the latest version of DXO Pureraw against the noise reduction feature included in the latest version of Lightroom. To my surprise Lightroom did a better job with the photo I tried. I used Lr at 50% and dxo at default values in the latest algorithm. The last time I did this comparison Pureraw was in it’s 3.x version and at that time it worked better than LR. Now it’s the opposite.

I’ve heard a lot of people say that Lightroom’s current version seems more natural, and I saw some other comparison make a similar claim about that. I guess it’s an arms race between these various software companies, and it will come down to the most clever programming, model selection, gigawatts of power, and who can throw in the largest amount of data, probably in the exabyte range…..