The Df is a very controversial release, I would say perhaps the most controversial one in Nikon’s DSLR history. After Nikon teased the public with its short videos that slowly revealed parts of the camera, many were excited to see something completely different than a traditional DSLR. Videos titled “it is in my hands again” and “no clutter, no distractions”, with constant repetition of “Pure Photography”, hinted at a camera that combines old style Nikon film cameras with a modern digital sensor. Nikon “Df”, a “Digital Fusion” of retro style and modern technology, became an instant hit on the Internet and one of the hottest topics of discussion and speculation on photography sites and forums.

As we got closer and closer to the release date, enthusiasts from all over the world started speculating on the features of the yet to be released Nikon Df and pointed at possibilities of seeing a mirrorless camera, electronic viewfinder and a myriad of other technologies we now come to expect from modern mirrorless cameras. Film shooters had their own list of must-have features, including a large bright viewfinder with a split focusing screen for easy focusing with old manual focus lenses. In a very short period of time, the Nikon Df, a fusion of technologies, became an over-hyped camera with very high expectations…

And then it finally arrived. When the dust settled and people realized that the Df is basically a DSLR with a retro design, D4 sensor and D600 guts that came with a $2750 price tag at the time when Nikon was pushing D800 sales in the same price range, all the prior feedback and excitement turned into a bunch of hate. And very rapidly. Nikon had not seen this much hate on a newly launched product in a very long time. Not even in the days when Canon was in the lead with their pro full-frame offers, while Nikon was still sticking to the APS-C format. On one hand, the Nikon Df was laughed at, made fun of, mocked and criticized for its appearance, lack of features and high price. On the other hand, those that actually own and use the camera highly praised its image quality, ergonomics, and overall performance. It seems like the particular group that is attracted to this camera knows exactly what to expect from it.

Indeed, the Nikon Df turned out to be a very controversial release. And my personal observation so far is that most of the hate you see on the Internet is coming from those that have never touched the Df and probably never will. And that’s OK, because the Df was not released to be loved by all. Nikon specifically targeted the camera at a small user base and as far as I know, they were quite successful at it.

Before writing this review, I really wanted to take my time and get to know the Df and get myself more accustomed to it. Compared to Nikon DSLRs that I have been shooting with for the past 7 years, the Nikon Df is very different, especially when it comes to its handling and controls. Having been shooting with different brand cameras and formats for a while now, I realized that some cameras just take more time to get adjusted to. Hence, writing a review a week or two or even a month after handling the camera is something I try to avoid doing. By now, I have had the Df for the past 4 months, so this review is a summary of my overall experience with the camera during this period.

Overview

When it comes to pure technical specifications and features, the Nikon Df is a combination of different technologies that are found on existing Nikon DSLRs. In a way, it is also a fusion of existing DSLRs: D600/D610, D800, and D4. It has the same autofocus system as the Nikon D600/D610, its top and back are also of magnesium alloy construction and it has similar limitations as the D600/D610 when it comes to the fastest shutter speed of 1/4000 or flash sync-speed of 1/200. It has the same weather sealing features as the Nikon D800/D800E and also has a dedicated AF-ON focus button on the back of the camera. Its low-noise 16 MP sensor is very similar to the one on the Nikon D4. Just like the D4, it comes with no built-in flash.

Its firmware is also a mix of different DSLRs. For example, the Nikon D600/D610 has no center button instant zoom capability (during playback), while both the D800 and the D4 do. Since the Df has a number of similar features from the D600/D610, one might expect to see similar firmware limitations. However, that’s certainly not the case with the Df – not only does it have the same center button instant zoom capability (Menu -> Custom Setting Menu -> Controls -> OK Button -> Playback Mode -> Zoom on/off), it also has an advanced firmware feature for exposure meter coupling when using old pre-Ai lenses, which is not found on any other current Nikon DSLR.

What sets the Df apart from other Nikon DSLRs, is lack of certain features that have more or less become a standard on advanced / full-frame cameras. First of all, the Df has no video or time-lapse video recording capabilities. Nikon decided to market the Df “purely” for photographic needs, so it completely excluded video recording options. A rather interesting and unusual move, considering the popularity of DSLR video. Another omission is a dual card slot – the Df only comes with a single SD slot located underneath the camera (more on this under “Handling“). There is no built-in flash either. Lastly, aside from the flash sync port, the Nikon Df does not have infrared or 10-pin remote connector ports on the front.

At the same time, the Nikon Df tries to compensate for those deficiencies in other areas, and weight with bulk are two huge factors in Df’s favor. At 710 grams, the Df is Nikon’s lightest full-frame camera. And with its comparably short profile and a more compact grip, it is also smaller than the Nikon D600/D610 (although not by a huge margin). Other features borrowed from higher-end DSLRs include a dedicated AF-ON button and a large rotary dial, similar to what one would find on the Nikon D800/D800E cameras. The Df features a usable 1:1 Live View, which is a world better in comparison to the ugly interpolated Live View of the D800/D800E.

The big subject of the debate is the top “retro” navigation of the camera, which obviously looks similar to classic SLRs like Nikon FM and nothing like a modern DSLR. Nikon used different dials for such functions as ISO, Exposure Compensation, Shutter Speed, Shooting Modes, On/Off and Camera Modes, along with the traditional rear dial and a small rotary front dial for setting different exposure parameters, similar to modern DSLRs.

In short, the Nikon Df is a mix of features and limitations mostly borrowed from existing Nikon DSLRs, plus the retro design. How does it all roll into the shooting experience? Read on to find out what we think.

Nikon Df Specifications

- Sensor: 16.2 MP FX

- Sensor Size: 36.0 x 23.9mm

- Resolution: 4928 x 3280

- DX Resolution: 3200 x 2128

- Native ISO Sensitivity: 100-12,800

- Boost Low ISO Sensitivity: 50

- Boost High ISO Sensitivity: 25,600-204,800

- Processor: EXPEED 3

- Metering System: 3D Color Matrix Meter II

- Dust Reduction: Yes

- Weather Sealing/Protection: Yes

- Body Build: Top / Rear / Bottom Magnesium Alloy

- Shutter: Up to 1/4000 and 30 sec exposure

- Shutter Durability: 150,000 cycles

- Storage: 1x SD slot

- Viewfinder Coverage: 100%

- Speed: 5.5 FPS

- Exposure Meter: 2,016 pixel RGB sensor

- Built-in Flash: No

- Autofocus System: Multi-CAM 4800FX AF with 39 focus points and 9 cross-type sensors

- LCD Screen: 3.2 inch diagonal with 921,000 dots

- Movie Recording: N/A

- In-Camera HDR Capability: Yes

- GPS: N/A

- WiFi: N/A

- Battery Type: EN-EL14 / EN-EL14a

- Battery Life: 1400 shots

- USB Standard: 2.0

- Weight: 710g (body only)

- Price: $2,749.95 MSRP

A detailed list of camera specifications is available at NikonUSA.com.

Retro Controls

Handling-wise, there is a lot to say, thanks to the retro design. Since I have only been recently exposed to film cameras (I bought a Nikon FG with a bunch of old Nikkor lenses before the Df came out), I knew it was not something I would feel accustomed to from the start. And initially, that was certainly not the case – things felt odd, out of place and slow at first. Some things I just could not make sense out of and still cannot (more on that below). As I used the camera more and more, those retro controls did sync in though and I eventually got used to them. Let me go through each dial and explain how it all comes together.

Let’s start out with the dual ISO / Exposure Compensation dial, which is located to the left of the pentaprism / viewfinder. A few people complained about the large ISO dial, questioning the need to put it on its own dial. Looking at my Nikon FG film camera, the ISO dial was in fact on the left side and it was part of the exposure compensation dial. Obviously, each film has its own sensitivity, so the ISO part of the dial is only a placeholder, meant for the photographer to simply remember which film was put into the camera. Nikon took the same idea for the Df, but made a separate ISO dial in 1/3 steps from L1 / ISO 50 to H4 / ISO 204,800. So when setting the camera ISO, you must use the dial – there is no place in the camera menu where you can change it.

That brings up a slew of questions, specifically in regards to the Auto ISO function. A number of our readers initially asked me if Nikon killed the Auto ISO feature and that’s certainly NOT the case! Auto ISO is alive and well and it is implemented the same way as on the latest Nikon DSLR cameras. When you set the ISO on the dial, that basically becomes the minimum ISO sensitivity. When you go to Auto ISO sensitivity control in the camera menu, you can still set the maximum ISO sensitivity and the minimum shutter speed, with advanced Auto controls (Slower -> Faster). So if you like Nikon’s Auto ISO feature (which I personally love), it is still perfectly usable and not any different than Auto ISO you will find on other DSLRs.

ISO values are always locked, which means that you must press the little button on the side of the dial to be able to rotate it. You can do this with your left hand easily – simply press the button with your thumb and rotate the dial with your index finger. You don’t even need to take your eye off the viewfinder since the change in ISO values can be displayed on the bottom of the frame. The only thing is, if you need to make big jumps, say from ISO 100 to ISO 6400, then you will need to rotate the dial over and over again, as you have to go through each ISO in 1/3 EV steps. I had mine mostly set at ISO 100 and I used Auto ISO quite heavily in “Auto” minimum shutter speed mode.

Exposure Compensation was another area of initial complaint for me. Having used Fuji cameras, it was first a little odd to have to press a button to rotate the exposure compensation dial. But then I started remembering times when exposure compensation was too loose and changed accidentally on those Fuji cameras and then I realized that it was not such a bad decision by Nikon after-all. In addition, looking at my Nikon FG, I also realized that Nikon has had that lock on exposure compensation dial for a while now.

One of our readers complained that the exposure compensation dial requires two hands to change and it should have been on the right side of the camera. I disagree. First of all, you can easily set exposure compensation with just the left hand, again, without the need to move your eyes away from the viewfinder. Simply press the button with the left index finger and use the middle and thumb fingers to rotate the dial. As you rotate the dial, you can look at the same -+ indicators inside the viewfinder to find out where you are at. In terms of the location, I don’t mind the dial to be on the left. Nikon probably could have swapped the PASM dial with the exposure compensation dial, but it would have looked awkward due to the sizes of these dials.

To the right of the pentaprism / viewfinder, we find another large dual dial – Shutter Speed and Shooting Mode. I really like the way Nikon designed the Shooting Mode dial – instead of the traditional rotary dial with a lock, this one is a switch that goes from Single (S) shooting mode to Mirror Lock-Up (Mup). The only problem is for people with large fingers. When the Shooting Mode is set to “S” (Single), there is very little space between the dial and the On/Off switch. If the index finger is not small/thin enough, it can be difficult to move it to another position.

The Shutter Speed dial is the one that probably received the most negative comments on the Df – and rightfully so! Some people pointed out that the way Nikon designed the Df is counter-intuitive and downright wrong, because the shutter speed could read one value on the dial, while being totally different in certain camera modes. Having been using Fuji cameras during the past 6+ months, I do agree that Nikon screwed up with the design and ergonomics here. Instead of having a separate dial for PASM camera modes, Nikon should have taken a different approach by having one more aperture value setting called “A” (Auto).

So if you wanted to switch to Program or Shutter Priority modes, you could simply rotate the front dial till you got to “A” and the aperture would be automatically controlled by the camera. Instead of the 1/3 step option on the Shutter Speed dial, Nikon could have added another “A” (Auto) mode, which would set the camera to either Aperture Priority mode or Program Mode. The problem with 1/3 stop Shutter Speed increments is already addressed through the Custom Setting Menu->Controls->Easy Shutter-Speed Shift (f11) (once turned on, the camera allows to go 2/3 of a stop up and down the selected shutter speed, similar to what Fuji cameras do).

For manual mode, you would have to set the Shutter Speed dial and either rotate the aperture ring on the lens, or rotate the front dial to set a CPU-lens to a certain aperture. This approach would have completely eliminated the need for the PASM dial and make it impossible to see wrong/different Shutter Speed values on the dial at any time. What is the point of having the “Easy Shutter-Speed Shift” option AND the 1/3 STEP on the shutter dial along with the ability to select different camera modes? Seems like Nikon wanted to keep the current way of changing shutter speed and aperture instead of fully committing to the retro style, so it just mixed it all up together. Personally, I ended up mostly leaving “1/3 STEP” on the Shutter Speed dial (which allows setting the shutter speed manually in 1/3 increments using the rear dial), because I did not see the point of using a set value.

On the other hand, Bjørn Rørslett, who I deeply respect and follow, sent the following comment to me on the Shutter Speed / PASM dials: “I do disagree with the comments on the shutter speed dial and MASP switch. These are entirely logical and date back to the late ’80s (F4). They are kept for good reasons. Each photographer has to set up the camera for his or her main usage pattern and even though I mainly use the Df at ‘M’, the other settings have definitive advantages for special cases. Other users will put more weight on ‘A’, ‘M’ or even ‘P’. The good thing is Nikon understands the users are vastly different and lets them have the choice.” So there you have it – Bjørn disagrees with my above remarks because he has seen a similar layout on the F4 in the past.

Here is an example of how screwy this Shutter Speed dial is. If you use a modern autofocus lens and set the camera to either Manual Mode (M) or Shutter Priority Mode (S) using the small round dial, the Shutter Speed setting will work as expected. However, the moment you mount a manual focus manual aperture lens (pre-AI, AI, AIs), the Shutter Priority Mode becomes completely useless, no matter what Shutter Speed you set it to – the camera will automatically set the shutter speed and will disregard the set value on the dial.

Instead of this behavior, Nikon should switch the camera to Manual Mode whenever the shutter speed dial is set to a particular value. And better yet, if the PASM dial did not exist in the first place, changing the shutter speed would have automatically switched to Manual Mode, as it should. As of now, the PASM dial is a complete waste that occupies the already tight space. In addition, it is somewhat painful to use, as it requires lifting it up to change the setting. So if Nikon eliminated it, the On/Off / Shutter Release dial could have been moved to its place, or more space could have been created for the top LCD.

Speaking of the top LCD, while it does show some of the vital information like shutter speed, aperture, frame count and battery life, it is too small to accommodate such settings as shooting mode, focus mode, etc. When mounting an autofocus lens, if you need to change any of the AF settings, you must look at the rear “Info” LCD screen that contains more information – it automatically lights up when the AF button on the front is pressed. That’s certainly counter-intuitive for those that are used to look at the camera settings from the top LCD.

I am more or less neutral to the On/Off dial, along with the Shutter Release button. I found the On/Off dial to be a little stiff, but it is not too bad and will probably get easier to turn over time. The shutter release features a small threaded hole for those old manual-style remote releases. I have never used one, but I guess Nikon wanted to bring the old way of the shutter release on the Df in its full retro spirit.

In summary, Nikon should have done a better job of implementing the retro design and should have completely eliminated the PASM dial to make the controls more meaningful and usable.

Camera Size

A lot of people complained about the size of the Df and how it fails to be a small camera like the original Nikon FM-series. Many review sites have been comparing the Df to those old film cameras and pointing out how the Df fails to be a true retro / film-like camera because it is noticeably bigger in terms of height and width. I figured that this sort of commentary mostly comes from those that unfortunately do not understand what goes inside a DSLR camera vs a film camera. Film SLRs have far fewer components than DSLRs!

First of all, keep in mind that the flange distance MUST remain the same whether on a film SLR or a DSLR in order to be able to use the same lenses, so there are minimum requirements for the distance between the mount and the film / sensor. From that standpoint, both adhere to the same standards. However, when you look at a film camera like Nikon FM, note its backplate – when it opens up to load film, see how thin that back really is! You cannot make the back of a DSLR that thin – the camera has a LOT of components in-between that occupy space – the sensor itself takes up more space than film. It has a couple of layers of filters (AA, UV, etc), then there is a heatsink behind the sensor to keep it cool. Behind that heatsink, there is a large PCB, or what I refer to as the “motherboard” that houses the imaging processor, memory (RAM and ROM) and all sort of connectors to memory slots, battery, etc.

There is no way to make that PCB super small, as there are lots of components housed on it. Then behind the PCB, we have the LCD screen, which also takes up 5-6 millimeters of space. The battery compartment takes up a chunk of space to the right of the camera, so there is no way to use that space for extra components. Then there are a bunch of buttons, dials and the top LCD screen, which also take up space inside the camera. If it was not for those buttons and dials, Nikon could have probably made the Df shorter.

So you can see why making the Df as small as a film camera would be an impossible task to achieve! The only way to do it would be to decrease the flange distance. But then you know what that means – it would no longer be an SLR camera and none of the Nikkor lenses would work natively, requiring an adapter. I don’t think Nikon had the intention of making a mirrorless Df in the first place. Looking at the much smaller Sony A7R/A7 mirrorless cameras, one can easily see that the flange distance is very short, which is why the cameras are so thin.

Compared to a DSLR, the sensor on the Sony A7R/A7 is really close to the mount, located approximately in the middle of the camera (in width). All the above-listed components like the motherboard and the LCD take up the other half the camera. Roger Cicala and his team at LensRentals disassembled an A7R and you can see exactly what I am talking about by looking at some of the pictures – there is a lot that goes behind that sensor!

My point from all this – the Df simply could not have been made significantly smaller as a DSLR. Definitely not even close to the size of a classic film SLR.

Handling

When it comes to handling, the Df also needs some time to get used to. While I love the fact that the Df is so lightweight and compact when compared to the D4 and D800, it has a couple of annoyances that I wish weren’t there. First of all, if you have only used DSLRs in the past, the camera strap connectors are something that you will have to adapt your camera handling to. On most DSLRs, the strap is never an issue, since the shutter release button is located far from it. On the Df (and many old Nikon film cameras), the shutter release is on the top plate of the camera, so when you put your index finger on it, the strap can get in the way of other fingers that hold the grip. The best way to hold the Df is by putting the strap in between the index and middle fingers and that’s when it does not interfere.

The grip on the Df is noticeably smaller than on other Nikon DSLRs. Initially, I was spacing out my fingers and putting my pinkie on the bottom of the camera. After about half an hour of shooting, my fingers started to hurt. I then realized that it is better to put the fingers closer to each other and keep the 3 fingers on the grip. Once I adapted to this hand-holding technique, shooting with the Df was a breeze.

Another issue is the location of the memory card slot – I don’t understand why Nikon decided to move it to the bottom. Compared to a DSLR, having to open the battery compartment to change the card is certainly a hassle. Sony addressed this nicely on the A7R/A7 by putting the slot on the back side instead of the side, which helped keep the camera size small. Nikon probably moved the memory card slot to the bottom due to space constraints and if that was the case, then it would have been nice if two slots were provided instead of one.

While the battery door also has a retro twist-lock design, I have seen some reports of the door easily breaking and falling off. I personally have not seen such an issue on the two Df samples that I tested (one loaner and one owned), but I can see that it could be an issue since the door and the connecting parts are plastic.

Some people have pointed out that the Df does not handle well with large zoom and telephoto lenses. While that’s certainly not the case (since it is similar to the Nikon D600/D610 in size/bulk), I do agree with one thing – the Df was definitely made to be used with smaller primes instead of large and heavy lenses. Since the grip is fairly small and not as protruded, it makes it somewhat more difficult to hold a heavy setup. The target market of the Df is comprised of photographers that love shooting with compact, fast-aperture lenses. It is clearly not for those that lug around with 70-200mm f/2.8 zooms and superteles – the retro camera controls call for a lightweight setup.

The Df might take some time to get used to at first, but once you figure out the above quirks and work around them, handling gets more natural and fluid overtime.

Buttons and Controls

The back of the Nikon Df is designed very similarly as a modern DSLR. The playback and trash buttons are to the left of the viewfinder, the right side is occupied by the AE-L/AF-L, AF-ON buttons, and a rear function dial. The traditional 5 button layout to the left of the LCD is also there, along with the large rotary dial and “Live View” / “Info” buttons. Compared to the D800/D800E, there is a separate switch for changing metering modes. Aside from that, the back is pretty much the same as on a DSLR.

As a result, operating the camera is very similar to operating a traditional Nikon DSLR – easy to use and intuitive. The rear dial feels exactly the same way as a rear dial on my D800E (and not smaller like on the D600/D610), which is good. Nikon decided to change the front dial to a small vertical dial, most probably for aesthetic reasons. Again, this one took a little time to get used to, so I do not look at it as something very negative in terms of handling. After several months of use, the dial still seems to work well without any issues, so I do not foresee potential long-term issues with it.

Menu System

The menu system is also very similar to one from a Nikon DSLR – a lot more like the D800/D800E/D4 rather than the D610. User preset modes are still the old and practically useless A to D custom settings banks. I wish Nikon borrowed this part from the D600/D610, which have proper user preset modes right on the camera dial. It is a huge nuisance to go into two different banks to set presets and it just seems like Nikon has been sticking to this inconvenient feature for too long now.

Aside from the missing Movie settings under Custom Setting and Shooting menus, everything else is pretty standard in the menu. The Playback and Shooting menus are very similar to what you would find on the D800/D800E. Other than a couple of missing options like primary/secondary slot selection, the only major difference I could find was in the Auto ISO menu – on the D800 it is called “ISO sensitivity settings”, while on the Df the title reads “Auto ISO sensitivity control”. Makes sense, since ISO is regulated through the top dial and not the camera menu.

If you are upgrading from an earlier DSLR like the Nikon D700, you will love the enhanced Auto ISO feature of the Df (which was first implemented on the D800/D4 cameras). When selecting the “Minimum Shutter Speed”, you now have an option called “Auto”, which will automatically set the minimum shutter speed to the focal length of the lens. For example, if you are shooting with a 50mm lens, the minimum shutter speed will be set to 1/50 of a second. If you can handle slower shutter speeds, you can set “Auto” to be 1/2 or 1/4 the focal length of the lens. Or if you have shaky hands, you can set it to 2x or 4x the focal length of the lens. Think of “Auto” as -2, -1, 0, +1, +2, similar to exposure compensation in full stops. If your focal length is 50mm, your “Auto” setting would look like this: 1/13, 1/25, 1/50, 1/100, 1/200. The default would be 1/50, but if you go one step slower your shutter speed would be fixed at 1/25 of a second, while going two steps faster would increase the minimum shutter speed to 1/200 of a second. This works with both autofocus and manual focus lenses. Many of us have been asking for this feature for many years now and I am very happy with this implementation, although I hope Nikon takes it a step further, by automatically compensating for VR as well.

The Custom Setting Menu has a few differences worth mentioning. Due to lack of a built-in illuminator (which Nikon should have included on the Df for focusing in low-light situations), there is obviously no “Built-in AF-assist illuminator” option. A bunch of other Metering/exposure settings like step values for ISO, EV and Flash are also missing due to the retro design. Most of the menu items under “Shooting/display” have been rearranged and the “Bracketing/flash” menu has a couple of new options like “Optional flash” and “Exposure comp. for flash”.

Just like the Nikon D800/D800E/D4 cameras, the Nikon Df also comes with an advanced “Exposure Delay” mode with up to 3-second delay (d10 in Custom Setting Menu->Shooting/display) that can be used in conjunction with “Self-Timer”. For example, you can set the Self-Timer to 5 seconds and turn Exposure Delay on with a 3-second delay. Once the shutter button is pressed, the camera will wait for five seconds, raise the mirror, wait for three seconds, then open and close the shutter, then put the mirror back down. This will prevent pretty much any sort of camera shake – the equivalent of using mirror lock-up (MLU) mode with a cable release.

The confusing “Multi selector center button” has finally been renamed to “OK button” – that’s where you can configure the ability to instantly zoom to 100% view when reviewing images (a very useful and cool feature that Nikon stripped out of the D600/D610). Strangely, the “BKT” button is no longer programmable.

Lastly, the Setup Menu also differs a little between the Df and the D800. The Df has a new “Auto info display” option that by default turns the info screen on the rear LCD. For whatever reason Nikon also eliminated the “Battery info” option to see charge levels, number of shots taken and battery age. “GPS” has been renamed to “Location data” and new menu options called “Assign remote Fn button” and “Wireless mobile adapter” for the new wireless remote control tool have been added. The “Retouch Menu” stayed identical, except for the “Edit movie” feature.

Camera Construction and Weather Sealing

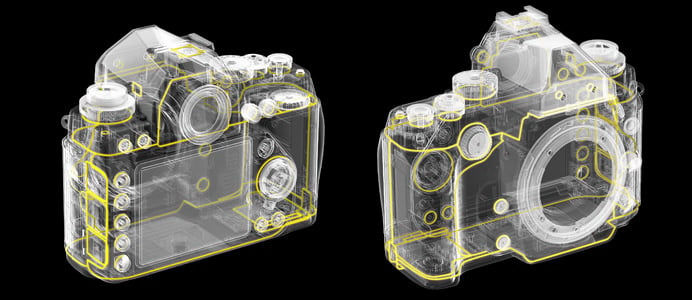

The Nikon Df is built a little better than the Nikon D610 in terms of construction – its top, rear and bottom are made from tough magnesium alloy (instead of just the top and the rear). In terms of weather sealing, it is very similar to both the D610 and the D800/D800E, so it also features various seals throughout the body to prevent dust and moisture from getting in. Colorado has recently seen very cold winter days, dropping as low as -25°C at night in the South Denver area where I live. I wondered how the Df would operate in such cold environments and I took it out a few times to shoot in below-freezing temperatures. While the battery certainly did drain faster in extreme cold, which is expected, the Df operated without any issues. I did not see any shutter lock-up or other serious issues, which is good news. Here is an image that shows the sealed areas on the camera:

Obviously, one should be careful in handling cameras when moving from very cold to warm temperatures – condensation could cause permanent damage to circuitry (which is why Nikon always lists 0-40°C as the operating range, even for the high-end D4). As long as you use a sealed bag when moving indoors or slowly move the camera from cold to warm temperature, you should be fine.

Table of Contents