The night sky is one of the most alluring subjects for landscape photographers. It’s also one of the most frustrating. If you’ve ever tried to do astrophotography, you’ve probably run into all sorts of issues: blurred stars, high ISO noise, and shallow depth of field.

What can you do about it? One answer is often overlooked, but surprisingly helpful and easy to put into practice: stacking images.

Fundamentally, the big problem with shooting the stars is that you lose a lot of image quality at ultra-high ISO values. Otherwise, you could shoot every Milky Way image at f/5.6 and 10 seconds (maximizing star sharpness) while simply using an insane ISO like 51,200 to get your image to be bright enough.

Stacking photos essentially eliminates that problem.

But what do I mean by stacking photos? There are two routes, one of which is simpler and more flexible than the other. But each has its place.

(All this assumes that you don’t have a problem with blending photos. If you need to capture everything in one image for whatever reason, take a look at our tutorials on Milky Way photography, getting enough depth of field at night, and the optimal settings for star photography.)

Table of Contents

Stacking Method One: Use an Astro Tracker

I’ll start with the harder-to-implement method because it’s easier to explain.

Today, you can find plenty of “astro trackers” available for relatively reasonable prices. These are rotating attachments for your tripod. Point an astro tracker at the North Star (or the Celestial South Pole), and it follows the movement of stars across the sky. Then, just attach your regular tripod head to the astro tracker and compose however you want.

How does this work with image blending? The answer is that astro trackers let you get sharp stars, but not sharp foregrounds:

By tracking the stars, you slowly add rotational blur to your foreground, and the photo is blurry anyway. So, you simply turn off the astro tracker, then take a second photo that prioritizes the foreground:

And then blend the two together easily in Photoshop or other photo editing software:

This method lets you get extraordinary levels of detail in the stars. Take a look below:

That’s pretty awesome, much better than I could have gotten with a single tripod-based image:

Astro trackers let you use almost arbitrarily long shutter speeds. You’ll only get blurry stars if you use extremely long exposures (10+ minutes) and longer lenses, if your polar alignment isn’t quite perfect. Or if you use an unstable tripod in windy conditions.

However, astro trackers aren’t always ideal. It worked well for the photo above because the foreground and sky had a very distinct separation. But if your foreground is something like a tree, you’ll run into major difficulties with this method. In the tracked image, where your stars are sharp, the tree will be a large blur. If you try pasting the sharp tree image on top, you’ll get a “blur halo” around it. Not a good look.

Luckily, there is a way to simulate an astro tracker without using one – and without capturing a blurry foreground in any of your images.

Stacking Method Two: No Accessories Needed

The second method of capturing insanely sharp stars at night is actually quite easy. It’s also pretty satisfying, since you get to use the settings you always wanted to use – no need for an astro tracker or other accessories.

For example, if you need f/5.6 to get enough depth of field, just use f/5.6. If you need 10 seconds of exposure in order to eliminate star trails, use 10 seconds. And if you need ISO 51,200 to get a bright enough photo, you can use that, too. (Though I actually recommend a lower ISO combined with brightening the photo later, as you’ll see in a moment).

Then just take several photos in a row using the same settings. When you get home, you’ll stack the photos in post-processing software to minimize noise.

In the Field

How many photos does this method take? It depends on the quality you’re after, the ISO you started with, and simply the time you have in the field. But I would take pictures for at least 4 minutes if possible, and ideally longer – more photos can only help. After all, you are simulating an ultra-long shutter speed with this method, so it’s no doubt that 10 minutes is better than 4, which is better than 2, and so on. (The smaller your aperture, the more photos you should capture, since you need to make up for lost light.)

What specific camera settings are best? The most important thing is to avoid any star trails in your images. If that means shooting at 5-10 seconds when normally you would shoot 15-30 seconds, so be it. This technique cannot get rid of star trails – nor can any technique I know of.

Beyond that, don’t be careless about your settings just because you have a bit more flexibility; you’re still trying to capture every last photon. In terms of aperture, pick what you need in order to get enough depth of field, nothing more. You’ll usually be good with a reasonable aperture like f/4 to f/8 (full frame equivalent).

And for your ISO, I know I said earlier that 51,200 can work fine, but I recommend sticking with a lower value in general. Quite simply, if you go too high, you might blow out some details (especially colors) in the stars. It’s better to shoot at a lower ISO like 3200 to 6400, even though the photo will look too dark, and then brighten it later (before you start doing the photo stack).

Some photographers will augment this method by taking “dark frames” to subtract patterned noise out of the image. However, this is not a requirement. But note that I do not recommend shooting with long exposure noise reduction turned on, since the delay from shot to shot may make stacking more difficult.

Post-Processing Image Stacks

Next, we’re going to stack the photos in specific astrophotography software designed for the task. It doesn’t really matter what software you use. Sequator is a popular free option for Windows, and Starry Landscape Stacker is a popular $40 option for Mac (I couldn’t find a free competitor, unfortunately). You can use Photoshop for image stacking, and you can find some tutorials/actions online if you’re interested. But dedicated software tends to do a better job in the more tricky situations.

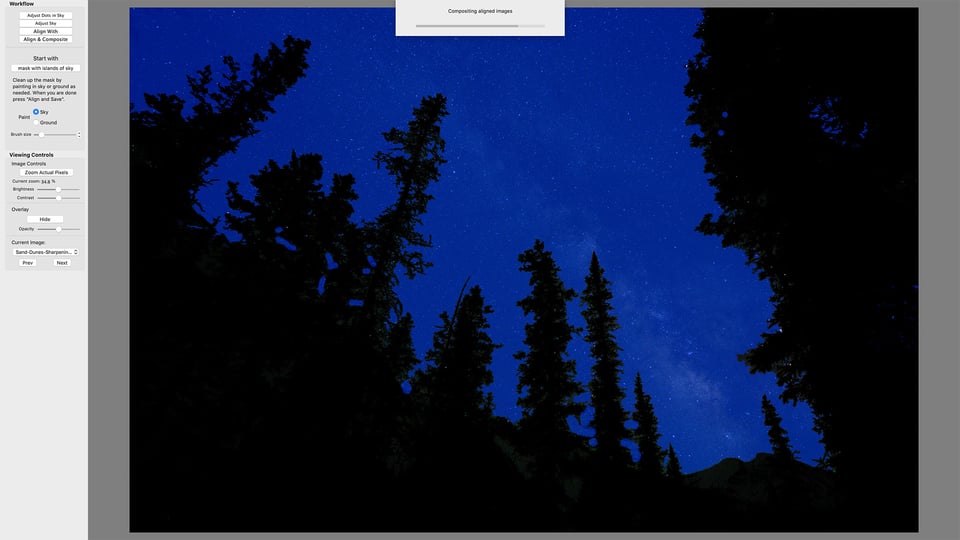

Load the photos into your software and begin the star-identification process (in this case, every red dot – most of them added automatically – representing a star):

Touch up any areas that the software masks incorrectly, like some areas of the tree below that the software accidentally labeled as the sky. This can take some time if you have foreground details like trees in your image since you’ll need to fix any errors in the auto-generated mask manually – but it is possible:

Once you do that, you’re done.

By stacking multiple photos together, you “average out” the noise and end up with tack-sharp stars. The level of detail in your nighttime photos has almost no upper limit, similar to using an astro tracker. Here’s the final image:

Even the tricky areas, like pine needles against the night sky, look great. Though, again, it did take some manual corrections to get the best possible result. (With this worst-case scenario image, I spent about 30 minutes of manual masking to get the final version.)

How does this compare in image quality to a single photo? Here’s a before/after with one of the 14 composite images I used to make this photo stack:

Not bad! Because I used 14 images for this stack, and each had a 10-second shutter speed, I was simulating a 140-second exposure. You can go much longer than that and capture even lower amounts of noise in your images. The limit is totally up to you.

Admittedly, this method does not always work right. If something in your photo is moving, like clouds across the sky, it can lead to some strange blur artifacts or extra noise. And in extreme cases like the image above – where practically the entire photo has trees that need precise masking – the software’s default attempt may require some correction.

Then again, the image quality benefits to this method are impossible to ignore. Plus, the fact that it can work in tricky situations like forest photography – where an astro tracker generally would not be feasible – makes it quite flexible overall.

Note that I still recommend taking one or two photos using single-image Milky Way settings – i.e., the ones we cover here – just in case. You never know if something might happen to make image stacking impossible. This also applies to astro tracking.

Conclusion

For years, my goal was to capture the Milky Way as sharp as possible in a single image, along with the foreground, too. I wasn’t willing to deal with astro trackers, and the idea of stacking images in dedicated software seemed to carry a lot of potential for error. (It’s also not allowed in certain publications and photography competitions, which I respect.)

But if you have no aversion to blending images, the two techniques outlined in this article are game-changers. You can shoot f/16 photos at night! Not to mention, with the second method, you can carry a lighter bag while capturing better results than before.

Cheating? It’s so useful that it almost feels like it has to be. To me, though, this is not cheating any more than focus stacking. But that’s something you need to decide for yourself. If these techniques do cross your line, our standard Milky Way photography tutorial may be more up your alley.

Hopefully, either way, you found this article to be interesting! If you have any questions about the finer points of image blending for night sky photography, feel free to leave a comment below.

Is it worthwhile stacking jpgs?

Stack the RAWs if you have them. If all you have are the JPEGs, stack the JPEGs! You’ll still see a major improvement. (Assuming the software succeeds in stacking them — it’s built for RAWs and sometimes fails with TIFF or JPEG.)

Really enjoyed your article and videos on stacking. One thing where there seems to be some debate is whether you should edit your photos (e.g. in Lightroom) before stacking them or afterwards by editing the stacked image. Does it matter, and if so what do you recommend and why?

I would follow the exact recommendations of the stacking software. In the case of Starry Landscape Stacker, I just import the unedited RAWs. However, you can also import mildly processed TIFFs as discussed here: sites.google.com/site/…ersion-1-9

Thanks for the really quick response. I am on Windows so have got a copy of Sequator.

I looked at the manual and it says, “RAW files are recommended. If you use TIFF instead, do not alter the linearity of data. Any processing except vignetting correction should be avoided”

Sorry, but don’t see any screens like your shots above when trying to stack……….think this article is outdated!

Are you using Starry Landscape Stacker? I just used it last week and still see all the same screens as shown in the article…

Well said .. thank you

I would like to know how you take these 10 or more shots .. do you take them manually one-by-one ( press the shutter every time ) or you use shooting interval like NPF suggest ?

It usually doesn’t matter either way, except to make your life easier. But I typically just press the shutter each time (with a self-timer) unless I’m taking more than a few minutes of exposures.

Now you can stack astrophotos using your smartphone by using Eagle Image Stacker application which supports most RAW formats.

Hopefully this weekend 8/13 I’ll have a clear night and will go out to Lake Thunderbird in Oklahoma to attempt my first astrophotography session. I’m going to use the second method and do image stacking. My camera has been converted to take H-Alpha and Visible spectrum. I’ll be using my Irix 15mm lens set on infinite focus. I’m sure I’ll have a lot of questions as I progress in this hobby but, my first question is do I lock onto the north star the best I can and then start the 5-10 second exposure for 10 minutes? With all those images will Sequator help in blending the photos and will there be manually editing involved.

The night sky images would look much better without Elon Musk’s satellites tracking through them.

Hi, another question for you. My dad is going on a camping trip, and I am planning on (trying) to take a milky way photo. I bought a remote shutter release for it too, but do i just leave the camera? Won’t the stars move out of the way eventually, or is there only a certain time limit you can shoot for so that the photos of the milky way all stay in a similar area? Secondly, I have taken a milky way photo before, but it looked pretty much exactly like this one: www.stocksy.com/15572…-the-beach

How do I make it more like yours? (One that includes all the purples and oranges and details) Is it to do with the time of year?

Thanks

This is a really helpful article but, because I am a bit dim, I haven’t figured out whether I need to move my camera, say left to right, to match the “star movement “ when shooting the stack. Also, similar theme, if I shoot with my camera in vertical position but want a wider field, can I take a stack in one position then move the camera direction to achieve a panorama and then take a second or third stack for blending – all stacks together or each stack separately and then blend the blended shots? (I am thinking of using a 35 mm f/2 lens to minimise coma, vignette get and corner distortion).

Gerald, there is no need to move your camera at all during these exposures.

In terms of creating a panorama, it’s doable, but keep in mind that each individual stack within the panorama may take several minutes to capture. This means that star positions will be very different for the later images in the panorama, and your final panorama may have duplicate stars in certain regions, leading to noticeable patterns.

Thank you. That’s really helpful.

Thanks for the article Spencer. I am facing problem when trying manually focus to infinity with NIKON Z 6 & NIKKOR Z 24-70mm f/4 S in night sky photography . I tried with the on screen bar to focus infinity, but maximum time end result is out of focus. How do you manage to keep sharp focus on stars? Can you help with the technique with 24-70mm f/4 S ?

This may help: photographylife.com/how-t…hotography