There have been some interesting debates lately about what’s ‘wrong’ with the digital camera market as people try to understand the rather dramatic decline in unit sales that has been happening over the past 4 or 5 years, with volumes down by half from their peak. I let my old, porous brain muse on this for a while and have some perspectives to share. One way to look at this situation is to simply accept that there is nothing fundamentally ‘wrong’ with the camera market at all in terms of sales volumes. From a macro-economic perspective we could view the digital camera market as functioning exactly as every other market has done when a breakthrough technology burst onto its stage. If we look at the history of various product markets the basic rise and fall of market volumes are predictable when they have been impacted by fundamental technological shifts – in the case of cameras it was of seismic proportions going from film to digital. When any kind of ‘game changing’ technology takes hold in any market there are initial and dramatic volume surges as consumers leave their current technology and adopt the new one. That huge upward spike in initial demand then declines quickly as soon as the initial ‘change-over’ market demand for the new technology has been met. Product life-cycle planning is based on these fundamentals.

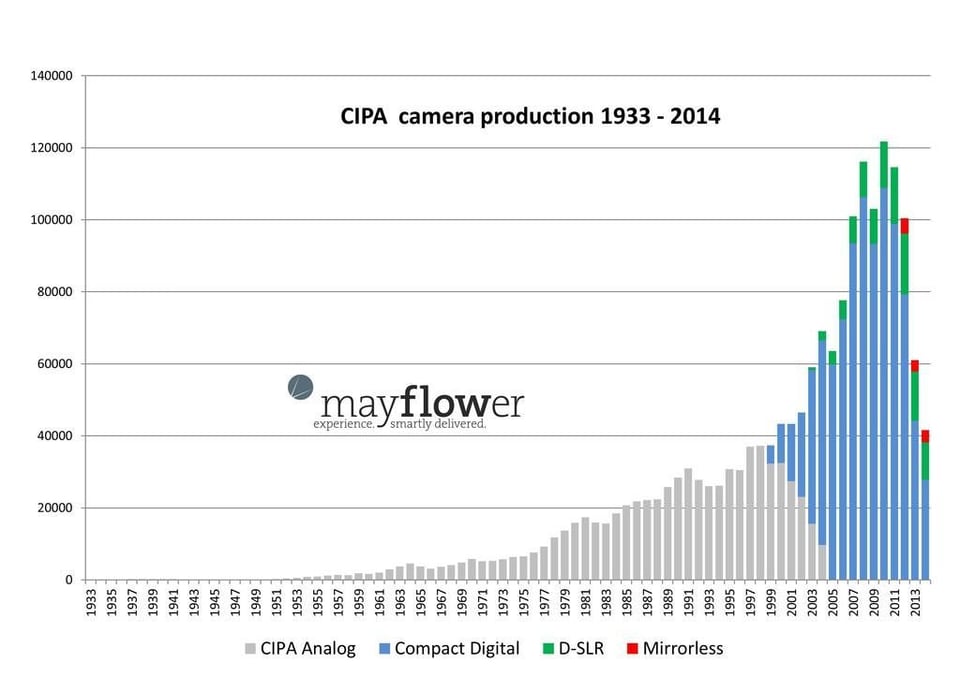

If we look at CIPA chart that was in the Mayflower report we see that camera sales were trending up at a reasonable rate (albeit with a few bumps along the way) until 1998 and remained reasonably flat when digital cameras were introduced in 1999. We then see a very fast uptake rate of the new technology that resulted in a complete market change over to digital cameras by 2005. This was really driven by the sales of compact digital cameras. This indicates to me that the new technology opened up digital photography to a huge new audience. The market kept growing strongly and reached its peak in 2010 and has been in sharp decline since. It now is only slightly higher than the market was back in 1998. This indicates to me that the pent up demand represented by the ownership of film cameras is completely used up and the camera market is now in a mature state. This type of demand curve is very typical of industries that have been impacted by a ‘break-through’ technology that fundamentally changed the market.

We can look at other markets to see these identical macro-economic impacts in play. Most recently the exact same thing happened with flat screen television sales. As more and more consumers adopted the new technology sales of flat screen TV’s went through the roof. That gave birth to ‘electronic superstores’ as additional distribution was needed to meet surging demand. Now, a decade after the big switch to flat screen televisions began, the switch-over has been completed by most consumers. The result is that the demand for flat screen TVs has plummeted and some manufacturers have either reduced their product offerings or left the market entirely. In essence the TV market transitioned quickly from ‘new high growth’ to ‘mature’. In Canada stores like FutureShop have been mothballed since there is no longer sufficient demand in the high ticket flat screen TV product category to sustain them. So, this phenomenon is nothing new, and is nothing that wasn’t predictable. It’s my view we are witnessing the same thing with digital cameras.

In high growth markets impacted by game-changing technology, companies fight furiously with one another by cranking out new product types and models so they can capture as much of the increasing market volume as they can. When timed correctly this is good business strategy since consumers are excited by the new technology and a lot of purchases are fueled by consumers buying willingly and often. Margins tend to be high under these market conditions and companies can ramp up R&D and bring out streams of new products with a good level of confidence that those R&D investments will be rewarded with good margins in what seems to be a continually growing market. If we look at the CIPA sales curve data we can see strong growth pretty much straight through to 2010. This growth helped to fuel the prolific increase in the number of camera models in the market.

There is a risk of course that if a company does not see the warning signs that the ‘switch-over’ market is peaking then they may make a mistake and keep investing in new products rather than changing from a growth strategy to one based on retrenching around core ‘winner’ products to prepare for the inevitable decline in market sales volume. I think we saw that with Nikon’s timing of the Nikon 1 product line and its introduction in the fall of 2011. The company arrived late to the party as the camera market’s ‘change over’ demand was already softening. The result was a less than stellar market reception and subsequent fire-sale prices to move over-produced units. One could argue of course that the specs of the camera, its value proposition, and marketing were weak and that’s what caused the luke warm market reception. I would agree that those factors had an effect. I would also suggest that if the camera market had still been in a frenzied ‘change over’ growth stage there would have still been plenty of pent up demand to absorb those new Nikon 1 products on a more profitable basis for Nikon. With the camera market starting its sharp decline in 2012 Nikon’s offerings would have been under price pressure right out of the gate.

One way of looking at this is that the number of film cameras in the hands of consumers represented the total ‘pent-up’ demand for the change over to digital cameras. As with any market, as the initial demand to move from old technology to the new replacement technology was increasingly met, overall market demand would naturally slow. There is a tipping point when the replacement of film cameras with digital slows down to the point at which companies serving that market need to retrench to align their operations with the reality of lower ‘mature market’ sales volumes. I think the camera market has already passed that tipping point and there is no going back. It’s my view that the peak market volumes experienced between 2008 and 2011 are never coming back because the pent up demand of film cameras that drove those markets is now gone. The switch from film to digital cameras is basically over.

I don’t see the decline in unit sales in the digital camera market as having anything to do with product complexity. There are plenty of compact, automatic cameras that can meet the needs of consumers who want simplicity. To me we are simply witnessing the classic macro economic demand pattern that is associated with the uptake rate of new technology.

Is the decline in camera sales volumes over? I don’t think so. I believe it will continue to decline, albeit at a much slower rate for many years to come. Why? The under 30 crowd is just not interested in traditional cameras in the same way that we ‘old geezers’ are. Many of these consumers don’t even think about the existence of a ‘camera market’ at all. Their lives revolve around social networking, checking the FaceBook status of friends and living their lives centred around digital communications.

I may be viewed as a bit of a lunatic for saying this but I don’t think smartphones compete directly in the camera market at all. I think they represent a completely different market of ‘digital communication devices’ which just happen to include digital imaging capability. The evidence of this stems from the fundamental motivation that consumers have when they make a purchase. When you or I buy a camera we do so with the specific and primary intent of taking pictures. I would find it hard to believe that anyone buying a smartphone does so with that same, primary intent. I think they buy a smartphone because they want to connect to the world around them and communicate digitally. This is a very different motivation and need than that of a camera buyer, and as such they represent a different market. That’s not to say that a lot of people that bought compact digital cameras in the past haven’t ditched them and now take all of the images they need with their phones. They have and do. What I am suggesting is that their initial need for a compact digital camera to fulfill their imaging requirements has been supplanted by a need for the much more powerful and broad-based digital communication capabilities of their smartphones. I believe that unless companies like Canon, Nikon, Olympus and others re-define themselves as manufacturers of ‘digital communication devices’ rather than camera companies or digital imaging companies they will never develop the integrated digital communication devices that those consumers want and need. This leads me to think that smartphone owners do not represent a meaningful marketing target for camera companies.

All these young consumers want, or need, are images that are of high enough quality to look good on their FaceBook pages and other social media. They live in ‘now snapshots’ that are quickly uploaded, then deleted from their social networking sites and updated with other more recent information. They are operating in a market that is defined in a completely different way. This isn’t good or bad. It simply is what it is. These new consumers don’t want or need cameras, they want digital communication devices that are also capable of producing digital images. They don’t want multiple devices. They want one that does it all. Cameras will never do that for them.

To survive and remain profitable camera and lens companies need to understand that they are in a mature camera market. The proof of that is in the CIPA data. It is time for camera companies to retrench and focus on core, profitable products as they wait for the next truly ‘breakthrough’ technology to hit the photography market and drive up demand again. How long could that take? Who knows – this most current breakthrough took quite a few decades to arrive.

What can we expect in the future?

Companies will need to change their marketing strategy and look for niche market opportunities in which to differentiate themselves. We have already seen some of that happening with companies like Nikon targeting the landscape and studio markets with high density full frame cameras like the 36MP D800 and its updates. Other companies like Sony are going in the opposite direction by reducing pixel density to improve low light performance. Companies like Fuji are developing proprietary sensor technology to try and differentiate themselves. Panasonic has been focusing on meeting the needs of hybrid shooters who need a camera that is equally adept at still photography as well as video – thus the continued development of the GH4. Panasonic is also focusing on high end bridge cameras like the FZ-200 with its unique f/2.8 constant aperture long telephoto zoom capability.

These signs are good as it shows that there are some glimmers of hope that manufacturers are making the strategic switches they need to make.

Much more has to happen though. Manufacturers need to stop introducing new model after new model that offer only slight, incremental changes to previous ones. This is simply wasteful and ultimately costs consumers money in terms of R&D and marketing dollars spent to market almost meaningless differences in new models.

Manufacturers need to listen to their customers more and stop introducing half-baked features in their cameras like the 4K video in the Nikon 1 J5 that can only shoot at 15fps. This is nonsense as the video is choppy looking if there is any movement with the main subject or if background elements like water have wind ripples on them. Manufacturers need to learn to stop putting new features on cameras that don’t really add any value for buyers. And, if nothing else they need to make sure those features actually work up to the expectations of customers.

Marketing decisions need to be much more carefully planned and executed. If we look at the CIPA data it looks like the ‘new normal’ will likely be demand levels that were common back in 2001 and 2002. Given these lower market demand levels, companies will need to be very concerned about the production volumes of individual models so they can sell a sufficient number of them to cover their fixed costs and generate some margin. I find it hard to believe that given where the camera market volumes are now that every camera model out there today is profitable. My guess is probably less than half of the models out in the market today generate a profit for the manufacturer. I have a feeling that ABC (activity based cost) accounting is sorely needed by many camera and lens manufacturers so they could intelligently cull their bloated product lines and get rid of money-losing products.

Camera companies need to make the switch to a niche market differentiation strategy and look for specific opportunities to target the needs of small, specific market segments and then try to own those segments. This means the manufacturers will need to listen to their customers more and be very strategic with their new product development.

There will be an increase in ‘behind the scenes’ manufacturing cooperation between various manufacturers. Even now many buyers of ‘big name’ lenses would be shocked to learn what company actually built the lens they paid ‘premium dollars’ to own. Of course in the bigger scheme of things it doesn’t matter anyway – as long as buyers get the performance they seek, the point of manufacture is a moot point. This is the essence of branding and premium pricing.

I think one of two things will happen – individual camera companies will reduce the number of camera models that are currently offering (which is the prudent and strategically sound thing to do), or some of the companies out there will eventually fail and disappear or be merged with other companies. Some analysts have been predicting that only Canon, Nikon and Sony have the volumes needed to survive. I think this is a bit simplistic. It will come down to which companies can manufacture niche market products in sufficient volume to cover their fixed costs, generate healthy margins and a profitable bottom line. If they’re smart some of the smaller competitors may be able to do this as well, or better, than the big boys.

I think we’ll see a lot more joint initiatives in terms of product development. We see this happening now with companies like Nikon and Tamron filing a joint patent on a new 200-500 lens. This makes sense to me as the cost to bring new products to market will keep escalating and companies will need to forge these kinds of alliances to be able to compete effectively. This phenomenon isn’t new. The automotive manufacturers have been doing joint ventures and alliances for decades. The size of the camera market simply cannot sustain the current number of makes and models. The key to survival will be focusing on building production volumes of fewer, more profitable models and walking away from unprofitable products. Shared production facilities could be a future reality.

Some companies like Nikon will need to assess whether it makes economic sense for them to continue to develop and market 3 major formats in terms of CX, DX and FX sensor models. As overall camera volumes decline I personally can’t see this being sustainable. Obviously no one knows the outcome. My best guess is that 5 or 10 years from now the DX line of bodies and lenses will likely disappear. I know this sounds bizarre, but from a marketing strategy perspective I think it could make sense.

As market volumes fall so does the purchasing power of the manufacturers vis-a-vis their component suppliers. At some point Nikon will need to decide where its best margin opportunities lie. As the baby boomers age they are looking for smaller and lighter gear so my take on it is that there is a lot more upstream potential for CX based product than DX. As a result I think Nikon will put the bulk of its R&D dollars into its CX and FX product lines and do two fundamental things that will allow them to exit the DX market. First, they will work hard to improve the image quality performance of the Nikon 1 product line so it can encroach on the bottom end of the DX market. Second, they will focus their energies on reducing the production cost of their FX cameras and bring their costs lower and lower. One way they can accomplish this is by ramping up sales of FX models, buy more full frame sensors and drive their manufacturing costs down. If they can get an entry level FX body (albeit with stripped down features) down to the $700 to $800 range over the next 5 to 10 years, and improve the image quality of the Nikon 1 line, they can make the DX product line redundant. Nikon has already been demonstrating its willingness to design and produce good quality FX lenses at much more market sensitive pricing with lenses like the 85mm f/1.8G, 50 f/1.8G, 28 f/1.8G etc. I see this pattern of lens development as a good sign that Nikon will be focusing on the FX product line a lot more in the future.

Other companies will face their own sets of tough decisions as they contract their production to focus on their most profitable products. Eventually I can see the day coming when only a couple of manufacturers may be offering a specific type of camera and are recognized in the market as the best for that specific application. Panasonic, for example, may end up positioning itself as the hybrid camera specialists with their GH4 product, and have a secondary focus on high end bridge cameras that feature constant aperture zooms. Fuji may eventually become recognized as the best small size format camera for landscape photography because of their proprietary sensor design. Once this type of specialization begins to happen I think the price of cameras will begin to rise and consumer choices will be more limited than they are today. These are just my musings of course and not based on any specific information.

So what can we do as consumers to take advantage of the fundamental change that is happening in the camera market, or at least not be burned by them? The first thing is to really be brutal with ourselves and question whether we really need that ‘new’ camera body. What does it really do that is so much better than what we already own? And, even if we can identify that – do we actually NEED that difference and are we really willing to pay for it? When we ask ourselves a tough question like that and when we’re honest with ourselves we’ll likely come to the decision that we don’t really need to spend the money. During periods of macro market decline like the one currently being experienced by the digital camera market we can expect a period of rapid model changes as companies scramble to try to achieve an advantage over their competitors, regardless of how small and how short-lived that advantage may be. Their near term goals will simply be to meet their sales and margin targets as best they can. Consumers need to be on guard against hastily conceived and produced products during these turbulent times.

If we do decide that it does make sense to buy that new camera body we should just wait and keep our powder dry for a while. That new body will be available a bit down the road at a discount, plus all of the ‘new model’ bugs should also be worked out. And, the reality is there will likely be yet another minor model tweak just around the corner anyway.

Make no mistake, many folks out there suffer from GAS (gear acquisition syndrome) and they’ll want to continually update their gear. That means that there will always be a lot of good, used gear on the market at decent prices that may help us upgrade affordably.

At the end of the day we need to remember a simple truth…it is the photographer behind the camera that creates the image. The camera is simply a tool to capture it. Having the latest and greatest camera won’t make you a better photographer – only your dedication to your craft and honing your skills will do that for you.

Article is Copyright Thomas Stirr. All rights reserved. No use, duplication or adaptation is permitted without permission

There is nothing to be explained as normal business in action, and nothing that could not have been predicted. Yes, the smartphone has killed off most sales of small-sensor compacts .. but only someone clueless about photography would ever think that smartphones can challenge the capabilities of large-sensor cameras, regardless of the cleverness of their software.

When a market is saturated of course sales fall. There was a surge in camera sales when digital cameras became affordable and as the early offerings improved rapidly. Now that all “serious” photographers have one or more digital cameras that is good enough for our needs there is little reason to “upgrade” despite all the shills and propaganda telling us that we “should” or “need to”.

And almost any DSLR or MILC made this century is “good enough”.

The most simple answer to what happend is that the move from film to digital created a classical bubble. It was like a flood hit the analog photography and made it obsolete and in less than a decade everybody made the move to digital. The fast move of technology also meant some upgraded several times, increasing the bubble even further.

Now when most already have made the move and most digital cameras are good enough since a couple of years sales slow down rapidly. Especially for simple compacts as many are happy with their smartphones and don’t want or need to carry an extra device just in case they want to take a photo. Only in special cases like holidays consumers would take a camera with them.

I agree there will naturally always be a core of pro and amateur photographers who have a real need and interest in photography and therefore will continue to buy traditional cameras. Question is how big that core is?

Because as I noted in the post to the other article consumers also started buy more SLRs in the 1970’s and created a boom in sales for InterChangeableLens cameras that lasted until today. But now, and in future, when there are so many alternative cameras, will consumers continue buy traditional ICL cameras in the same amount as before? That is the multi million dollar question. Nishe offerings like superzoom-, rugged action- and UnderWater-cameras should certainly still find their buyers. But the rest?

One should also note that the Mayflower chart for camera sales based on CIPA figures doesn’t show the whole picture. First, as I understand, it only shows Japanese camera sales, completely ignoring the big western camera production. It propably also do not show simple cameras at all and maybe not that many compacts from the earliest years.

What not many younger people know today is that Nikon was mostly selling cameras to pro photographers and advanced amateurs until they introduced the consumer camera Nikon EM in 1979. And their first AF-compact didn’t arrive until 1983. That was quite late. It seems Nikon only after seeing the success of Canon AE-1 decided to enter the consumer market.

The Nikon 1 system is also a consumer offering. And like Nikon EM and its series E lenses it was late in the (mirrorless) market and have several limitations. It’s unclear what ideas Nikon had about Nikon 1. My guess is Nikon simply had developed that fast AF that demanded a smaller sensor with enough DOF for accurate AF and thought this is what soccermoms and -dads dreamt about. The latest Nikon 1 cameras indicate Nikon took note of the smartphone boom and decided smartphone users will be the target group upgrading to Nikon 1 as the cameras now use the same memory card standard.

But flirting with the consumers have alienated some of Nikons core customers who would have preffered a proper and more serious mirrorless system, something like the Fujifilm X system. On the other hand what is unique for the Nikon 1 system are propably more interesting for photographers than consumers. In essence Nikon built a camera system with features interesting for photographes but crippled the compatibility to the rest of the Nikon system and try to sell it to consumers. Makes sense?

It’s not that I dismiss the 1″ sensor because of its size. While bigger sensors certainly have their advantages in ISO capability and shallow DOF control a smaller sensor is good for most photos as we today mostly look at them on a screen. And I certainly do not dismiss photographers for buing into Nikon 1 if they see it fulfill some of their needs.

If only somebody could build the perfect 1″ zoom compact, something like Sony RX100 II with built in flash and hotshoe, but a good EVF (preferably the quality of the one in X-T1 or E-M1) at the left side of the LCD and control buttons beneath (one for ISO, but of course also Auto-ISO function for all exposure modes including manual), with a longer zoom, at least around 140-150mm FF eq with at least f/4 aperture at the long end, shutter speed dial and aperature control ring around the lens, a good grip and max thickness including built-in lenscap of 2″/5cm, then I would happily make most of my photos with that camera as it would always be with me inside the inside pocket of my coat or jacket. The latter may be the reason we will never see such a camera as many would realise it is good enough for their needs and they therfore would not need invest in an ICL camera system!

For me the 1″ sensor is the perfect choice for high quality zoom compacts. As I previously shown in a post here at photographylife the size and weight advantage for a Nikon 1 system over a M4/3 system is such small that it is insignificant. The only lens making a difference is the Nikon 1 70-300 zoom as a hypothetical M4/3 100-400 zoom (I think Olympus or Panasonic seriously should think building as there would be a market for it) would be a bit longer and heavier. But still much more compact than FF 100-400 zooms.

The only other advantage except for AF is that Nikon actually sells many of their Nikon 1 lenses at decent prices. Many lenses for M4/3, Fujifilm and Sony E are in comparision not good value. The only other camera producers in the mirrorless world understanding the importance of having a set of lenses with fair prices are Canon with their EOS-M and Samsung NX.

If I would answer the question which brand have the most potential in the mirrorless world I would actually say Samsung. They have interesting technology, make their own sensors and sell a good set of lenses for very decent prices and as a company have a lot of resources. Unlike Canon, Nikon and Sony Samsung (except for the small 1″ offspring NX-mini) doesn’t split their resources and have to think about protecting the sales of a FF system. Therefore Samsung can offer a full line-up (Certainly with many holes yet to be filled and much to improve. But as said, the potential is there.) from entry level to pro equipment. The only other mirrorless that can compete is M4/3, mostly Olympus with som help from Panasonic. But they have financial problems and try to recoup some money with high lens prices. Fujifilm mostly target advanced photographers and have high list prices for their lenses. And no, I don’t own any Samsung gear except computer screens and a printer.

The future will tell if Nikon made the right bet with their Nikon 1 system and will win the race for the smartphone upgraders. The big IF is if they think they need an upgrade as smartphones already take more photos (and video clips) today than traditional cameras.

So what will the future bring? Well it is basically quite clear that the rapid fall of compact sales will continue. A future with zoom lenses on smartphones will wipe out the remaining sales of simple compacts. High end super-zoom and other speciality compacts will still be in good demand.

For ICL cameras DSLR sales will continue their fall. Not so much for Canon’s and Nikon’s FF DSLRs that may even increase sales. The bulk of the lost sales will be for APS-C/DX DSLRs. The problem for those are that they because of the use of a FF flange distance for the lens mount never can be a full system as compact as comparable mirrorless camera systems.

The main reason a lot of people still buy DSLRs is that the entry level cameras still offer better value. When mirrorless cameras can be sold with a good EVF (minimum 1.44MP, preferably +2MP) and have comparable AF at close to the same price DSLRs will only attract buyers who need more reach with FF tele lenses and best AF-tracking and those who still prefer an optical finder.

Mirrorless will mostly keep their sales as they are constantly picking up sales from people leaving DSLRs for a smaller system.

Nikon could certainly attract some buyers by offering a cheaper FX DSLR, like a D500 based on the D5X00 DX camera. But for most people than very serious photographers FF camera systems are too big and heavy. Also if one compare the size of old manul SLRs with primes in the Leica M range (wide to short tele) with comparable FF DSLR and latest lenses it is clear Digital cameras are much bigger, actually close to the size of many MediumFormat film systems! And those who used MF film cameras before now mostly use FF digital cameras.

I wonder if Nikon realise their FX cameras are now operating in a market before occupied by Bronica, Hasselblad and Mamiya? And what Nikon used to sell is now best represented by the Fujifilm X system as well as in part by other mirrorless systems. Nikon 1 in comparance, not because of image quality, but because of other limitations, just doesn’t cut it. And I am doubtful Nikon can replace lost DX DSLR sales with Nikon 1 sales. Canon on the other hand when they see it is the right time to stop protecting DSLR sales very easy can make EOS M a serious alternative by introducing better cameras with built-in EVF and more lenses.

To be competitive with their biggest rivals Nikon would have to start all over again by building a new camera with a bigger sensor, for exemple same size as the 1.3 crop in D7200 (that still could fit in the Nikon 1 mount) and using the same flash system as in the DSLRs, and of course a new set of lenses covering the bigger format. But for the time being Nikon is comitted to the CX format and have limited resources developing a completely new system.

Nikon might end up where they started as a producer of mostly pro FF cameras. But that also means they will lose a majority of the sales they have today. As it looks the traditional camera market is as a whole declining. If the traditional camera producers want to sell in volume in the future they will have to think outside the box and produce new types of non-traditional cameras that will appeal to consumers. How the market will develop will be interesting to follow and we will see in a few years what is happening.

Hello EnPassant,

Thanks for sharing a wide range of perspectives and adding to the discussion. In terms of a bridge zoom camera with a 1″ sensor, you may want to check out the Pansonic FZ1000. It has an efov of 25-400mm f/2.8-4. It also shoots 4K video.

Tom

I know about the Panasonic camera. Unfortunately it is just too big and doesen’t even fit in an outside coat pocket. If a camera is that big I have enough choices of DSLRs and mirrorless cameras.

I want the best zoom compact possible with EVF that will fit in my inside jacket pocket and I can have with me all the time. Max thickness of 5cm/2inch is therefore the limit.

But so far that camera has not yet been made.

90% of the photog out there are printing like 3R, if they actually print any. 3R, why do you need anything better? seriously? 24mp? with file size like 20mb per piece? and check it in a 20 inch monitor? :D

I think you are, by your definition, a “lunatic.” Smartphones have completely changed the game, and this isn’t people being done with switchover or you’d have seen a blip much earlier with digital — it’s people completely changing how they handle photography. P&S cameras, except for a few niches like extreme conditions (I’m thinking here underwater models from the major manufacturers plus GoPro), are dead, dead, dead. Despite the fact that the world’s population has doubled in 40 years and disposable incomes have grown enormously, we’re headed to significantly lower per capita camera sales than 40 years ago — we’re already at mid 1970s levels and falling — because of this basic fact.

Hi decisivemoment,

Thanks for sharing your perspectives.

Tom

I’m part of the ‘core’ camera market made up of people that want better image quality but I do also have a V3 that I can and do use as a point and shoot with RAW capability that I take full advantage of including D-lighting and selective NR, sharpening, and colour control points. I also use it for family travel with a suite of lenses. I’m still very interested in what the new J5 sensor can do – will be interesting and any DR increases will be very welcome. Also love video time permitting. And yes I have three Nikon DSLRs for serious, fun, and some paid work too and plan to continue to upgrade those as time and funding permit. Like many others here I alternate between getting additional or upgrading lenses when my needs are met by my current DSLRs and upgrading cameras when something compelling like a D400 (har-de-har) comes along. Lots of associates at work buy cameras in addition to their cell phones for special upcoming trips and milestones like children coming into play. Hopefully the camera market will plateau at a decent level for the camera industry to stay healthy and innovating, but scary times for sure.

Hi KnightPhoto,

Thanks for adding to the discussion! I agree with you that there is a ‘core’ camera market based on more discerning people concerned with image quality that isn’t going to disappear.

At this point it is too early to know if the camera industry will act in a cooperative and strategic way to take advantage of the huge growth of digital imaging in the cellphone market or not. If all of the camera manufacturers are smart they will see that there is a good opportunity to once again grow camera sales, but this time with current cellphone users.

To do this there will need to be another shift in need by consumers. This could very well happen. As these hoards of ‘new users’ of digital imaging in their cell phones become more used to the technology it is reasonable to assume that a certain portion of that market may want to experiment further with photography. When they do they will discover the limitations of their cellphones. At that point those consumers have a different need that cellphones cannot meet, and it would be a need on which camera companies could capitalize.

Given the fact that the camera manufacturers are all scrambling to hold on to as many unit sales as possible they many not be thinking strategically enough to see the future opportunity in a potential growing ‘camera need’ in the marketplace in the years to come.

Nothing in business is ever static as consumer needs ebb and flow.

Tom

There are now billions of cell phone users.

You’d think that a certain portion of that market would have experimented by now – if they were ever going to?

However, the ‘proper’ camera market is still collapsing.

I suspect almost all of the people using camera phones are perfectly satisfied with the output (especially as it’s constantly improving) and are not about to embark on anything as ‘complicated’ as a DSLR.

This apparent collapse is probably just a reversion to the same core of dedicated users who formed the mainstay of the film industry.

It just looks like a collapse because the expected ‘eternal growth’ has stopped, which is leading to panic among the manufacturers who have an evaporating cash flow and huge factories with thousands of employees about to lose their raison d’etre.

I’m not privy to any market research that various camera companies may have on the digital imaging market that may provide details on how they segment the market, what kind of consumer user group profiles they may have, how they identify and rank purchase criteria by defined market segment, as well as brand image profiles.

It would also be interesting to know if they have quantitative data on exit and entry rates of various digital imaging segments and what drives those consumer choices.

I agree with your assertion that the vast majority of current cell phone users would not enter into the DSLR market. Perhaps that’s why Nikon has patented a ‘build you own lens’ approach and is also looking into modular camera designs.

Tom

Can your Chinese toy camera (DSLR) match this scan from my $500 Epson scanner? 8×10 Ektar 100, and if you haven’t noticed, there are no diverging lines, because unlike the Chinese toy camera, my Deardorff has camera movements. Scanned at only half resolution (2000dpi).

Can you shoot birds in flight, motor racing or athletics events with your Deardorf?

I doubt that its ‘movements’ are fast enough!

You may find this interesting. I hadn’t seen anyone update this for a few years, so I made this. It shows what that often-cited graph would look like if you included smartphone shipments. I would argue that the camera industry is healthier than it’s ever been… but the brands we all think of as “the camera companies” aren’t participating.

If you think that smartphones aren’t the real cause of weak sales in the old-school camera industry – DSLR, mirrorless, compact, whatever – you’re smoking crack. Smartphones have huge advantages for the average person, or even for a “serious photographer”.

Name a camera from the old-school companies that does ALL this:

* is easy to use and learn – (some)

* is always connected to the internet and has easy social sharing abilities – (almost none)

* has interchangeable software via apps – (almost none)

* can do more than just take photos/videos – (almost none)

* can deliver good enough image quality for most popular purposes – (nearly all, hooray)

* is popular and ubiquitous, so all your friends have one – (mixed)

* is small enough to fit in a jeans pocket – (a few compacts, unless you have huge pockets)

* provides meaningful improvements via software updates – (a few, such as Fujifilm)

* is relatively inexpensive, especially on a contract, where the upfront cost is very little – (compacts)

No traditional camera can do ALL of those things, much less even a third of those things. Yes, you get better image quality, but you lose out on almost everything else.

Note before the ad hominem attacks begin: I use a Nikon D800 and 4×5″ large format film cameras for my serious photography, and almost never use my phone camera. But we are the exception these days in terms of the number of photographs actually taken, the number of cameras sold, and the number of photographers.

Hi Sven,

Thanks for adding to the discussion by sharing your graph. There are various opinions as to what constitutes the ‘camera market’…and everyone is entitled to their view.

Tom

So… the “camera market” should not include *all cameras* anymore?

If you don’t want to include ALL cameras in your definition of “the camera market”, fine, but you’re sticking your head in the sand just the same way as CIPA*.

My graph is apples-to-apples – all consumer cameras. The difference between it and the one you posted at the top of your article is so staggering that it should make you question your conclusions.

But if you want to turn a blind eye to something so obvious, go nuts. Just make sure you read up on the backfire effect so you understand the psychology of why you’re doing that: youarenotsosmart.com/2011/…re-effect/

* CIPA formerly included all consumer cameras in their *analog* numbers – SLRs, rangefinders, point and shoots, medium and large formats. Likewise with digital… up until it came to cameras on phones. Source: www.cipa.jp/stats…r100_e.pdf

Hi Sven,

My opinion on what smartphones represent is clearly stated in my article. Obviously your opinion is different than mine. All my reply was intended to point out is that you are entitled to your opinion. It appears that you do not believe that I am entitled to have an opinion that differs from the one you have.

Tom

There’s a bit more to it than “opinion” I’d say.

As you wrote yourself, certain types of “people taking pictures” have moved from the simplest film camera incarnations, and then digital P&S cameras (which were the *only* available option at the time) to smartphones/phones with cameras.

Are these people a different marketing target from an amateur or professional photographer ? Yes, definitely.

But it doesn’t mean that the “real camera” market evolves in a vacuum, disconnected from this trend ; these people are still here, they’re still taking photos, more than ever actually. Moreover, “actual” photographers do the same in a lot of circumstances, I know photographers who have a habit of practicing certain kinds of photography with their iPhone, and it’s no less *photography* than with their DSLR.

Camera makers contortion themselves in order to appeal to this broad audience in some way, it’s where most of the money is, they spend resources on it ; yet somehow these people (and sales) are too often cropped out of the general picture, which tells a completely different story ; Sven’s plot don’t do that and is a much more accurate (or maybe, “actually correct”) representation of the camera market state.

All of this discussion is basically opinion. The facts are more or less restricted to the reported sales of various products in the broad digital imaging market. How we as individuals interpret those facts and assess/judge/view what they may mean in the future is all opinion.

I’m with you on this one, Sven: to best understand how the camera market is changing, one needs to include all cameras — Smartphones most certainly included. So much of this discussion is focusing on population trends at the sacrifice of individual preferences/choices in cameras. But the population is comprised by individuals. There are a ton of people using their iPhones for commercial (i.e. paid) work. Seriously. And I’m sure there’s data out there somewhere showing how much. F-Stoppers regularly features articles on some creative doing something outrageous with their phone (whether whole motion pictures, or glamour shooting). The range of add-on cine and still lenses and accessories to Smartphones is also intriguing. It’s too limiting to ignore this subset of the “camera market” because it has influence on the camera market. It’s hard to parse out just how much influence it has on, say, a person also purchasing a dSLR or point-and-shoot, but it’s harder still to image Smartphones having no affect on the more “traditional” camera market. Where does that leave Nikon, Canon, et al.? Teasing that out is probably what Nikon and Canon are trying desperately to do.

As an aside, I totally use my iPhone for photography. My Instagram is entirely comprised of iPhone-only shots. And the processing I do to the pics on my Instagram versus my regular photography is also totally different, and not just because I edit all those shots in-phone, either: I use my camera phone for a totally different aesthetic than I do my dSLR; and I use my dSLR for a totally different aesthetic than my SLR. And incredibly, I’ve sold a reasonable amount of 12×12 prints from my Instagram portfolio. So many other people I know use services such as Instagram to substantially promote and support their photography business, too, so it’s not only a camera phone but a virtual and mobile portfolio that can also take, develop and digitally print images on the fly. Certainly there is a need to understand how this market affects the entire camera market. Thanks for putting up that data set!

Best,

Brian

Great plot, what are we talking about ? We are talking about image capture both static and motion. Why the growth comes with exponential decrease in cost and increase in convenience to share and be viewed. Thoughts that come to my mind…

1) What if Camera companies realized they were in the image capture business would their strategy be different

2) What about kodak/fuji if they knew they were in the imaging business.

Will DSLRs and medium format go away, likely not but more and more of the pictures will be captured by the masses with smartphones. They have the luxury of huge volumes to drive silicon and software innovation to further increase their adoption. The “camera” companies struggle in all the wrong ways and are fighting the tide. Hopefully they will get a clue and survive as I am a GAS, I can afford the toys, but find more and more my whole family and me find the iPhone6 and Plus more than meet 99% of my needs. They are more then good enough, even journalists will soon migrate to phones with lenses then unwieldy DSLR for press items. Two years ago and two phone generations ago it was 76%, 4 phone generation ago the P&S was 50% and DSLR 50%.. is it any wonder why one is growing and the other is relegated to the dark ages. Think HiFi what revolution have they adopted in Moore’s Law… very llittle. Traditional camera companies will follow down that route.

The peaks we see in the sales of most things usually has for more to do with fashion than with the underlying technology and its performance. What is deemed fashionable today quickly goes out of fashion whereas hardware technology and its performance continually advances.

It was, for a while, ‘cool’ to be seen carrying a medium-sized camera adorned with a plethora of complex dials and buttons, which seriously impressed the average person who didn’t begin to understand how to use any of those controls. Now, everyone can capture a reasonably fit-for-purpose photo on their camera phone therefore they are no longer impressed by the people carrying complex photographic gear. Being an expert, or even just being skilled, in a particular field of endeavour is currently widely considered to be the opposite of being ‘cool’.

The astonishing images produced by Thomas Stirr (and the many experts over the decades) ought to be more than enough to prevent people from trying to gain popularity on social media by posting selfies and their other hideously crap photos. But, most people currently prefer quantity versus quality and gossip versus truth. Such is modern life!

I’m humbled by your generous words Pete…thank you very much.

Tom

I agree with much of what was written in the article regarding the strategies the major camera makers are adopting, trying to cash in on the huge upsurge of people taking photos, and while I think there is a window of opportunity here, the approach taken is all wrong. I would even argue that the biggest barrier is not the cost of the investment. Of sure, it’s not cheap, the problem is what you do once you did plunk down say.., $1000 or whatever.

The biggest barrier by far is the huge disconnect between the previous photographic experience (smartphone) and this larger camera that is completely different. The scene modes they could just get rid of. I have never even heard of anyone using them. I saw a young man, sporting a Canon Rebel with a touchscreen, trying to take some pictures of a couple of very cute girls. So far so good. Having no clue what he was doing, he had it in live view mode, and kept stabbing at the screen trying to get it to shoot, with flash, then without, and no luck. After 4-5 tries, the girls gave him a half-hearted smile and wondered off.

You can argue he should learn and study and blablabla, but perhaps that was not his interest, and he just wanted to be able to take better pictures than his phone as promised by this so-called entry-level DSLR. Prior to the smartphone boom, the new buyers did not really have this expectation or practice but here the camera makers really needed to take this into account and find way to ease them into a new approach, and not punish them if they balk.

Hi Albert,

Thanks for sharing your perspectives! You bring up an interesting point that the camera industry needs to address…i.e. how to help people with little or no real experience with digital photography transition into the camera market, learn how to use more complex gear, and appreciate the differences in image quality. I think if the camera industry can somehow create a cohesive and cooperative approach to this issue it can help bring ‘phone photo’ folks into the dedicated camera market.

Tom

Olympus….needs to read your comment…!

Hi Thomas,

Good article, well written and informative, as are all of your articles here. I think the tremendous growth of camera sales was due to the rapid proliferation of digital cameras on the market, and what digital offered to consumers over film. I also know some news photographers where I am from in upstate New York that resisted digital and said they would never switch to it, but eventually did. Many people that jumped on the DSLR bandwagon, whenever a new model came out, would rush out to buy the latest and greatest camera (gas), which surely helped fuel the growth in camera sales even more. I think the drop in sales that we are seeing now can be attributed to a few different factors.

One, some new models that come out are not always a major upgrade to the model that they are replacing, and therefore, people aren’t rushing out to buy a new camera as often as a lot of them were before. I have a D800, and yes the D810 is an improvement on the D800 in some areas, (Group Area AF, Expeed 4, Native ISO and boost ISO), but for me, I did not rush out to buy the D810 when it became available. Not being a professional photographer, the D800 was still more than capable and adequate at this time, and suited my present needs, and therefore I saw no need to replace it simply because of “gas”. I would much rather spend my money on a new lens or other gear that i need. I think this is one of the main reasons we are seeing a drop in camera sales.

Two, IMO, as others have stated, phone camera sales have had a a great impact on camera sales. I know many people in my area, family, friends, co-workers, that all use their camera phones for taking pictures, and swear by them. A lot of them have digital cameras they bought during the growth in digital camera sales, but never use them now at all. Some of these phone cameras take pretty decent pictures, especially if you are taking pictures of mainly family gatherings, your kids, etc. Their opinion is, why do I need a camera when I have this phone that takes awesome photos. I have seen some camera phone pictures that have been printed to 8×10 and look excellent. What these people are saying is, they always have their phone with them at all times, therefore they always have a camera with them at all times, and don’t have to carry anything extra with them. I was at a very large retirement party for our church pastor and I brought my D800. The only other person that I observed there that day with a DSLR or even a point and shoot was the photographer that was hired to shoot that day. In fact, a few people even remarked, “look, someone who is using a real camera to take pictures, not their phone”. I thought that remark spoke volumes about the camera market. I think camera phones are probably the biggest reason for the decline in digital camera sales.

Three, then you have the people that I believe feel intimidated by today’s DSLR’s. I have heard many people say “look at all those buttons and knobs, I wouldn’t know what to press”. Even some of your smaller cameras seem to have this effect on people. This is just something I have heard people mention, so I am throwing that out there too.

Pros, serious hobbyists and amateur photographers alike will continue to purchase DSLR’s when they need to. Others, like myself, will purchase a new DSLR when a replacement for what we already own offers major improvements and features that we feel will benefit us. Of course, there are still those that suffer from “gas”, but I don’t think in the proportions that we have seen in the past.

Anyway, those are just some thoughts I have on the matter. Feel free to comment. Again, great article Tom. Love reading all your posts here on PL.

Vinnie

10 years ago I was at a class reunion party. Those bringing cameras with them all had digital compacts of various kinds. I was the only one using an analog film SLR (Nikon FA with 50/1.8 E loaded with Fujifilm 400 ISO color negative film. No flash).

Today I would take a digital camera because of the ISO advantage. Preferably a mirrorless camera becuse of the smaller size. But I would propably be as alone with that choice today as I was with my film SLR 10 years ago as I am sure everybody else would bring their smartphone.

Only thing remaining the same would be my photos still being more attractive and capture the atmosphere better because of using a real camera with a fast lens instead of using straight-on flash.

Hi EnPassant,

Thanks for sharing your experiences! Your comment tends to support the notion that there will always be a ‘core’ camera market made up of people that want better image quality. That’s one of the reasons that I don’t believe that the camera market is collapsing as some others state. I think there was a huge wave of demand that swept through because of the advantages of the new technology…digital…and now the market is finding a new equilibrium back to its core.

Tom

Hello Thomas!

A late answer as I haven’t had time before. Was a bit surprised you answered on my short notice. I wrote a long post for the April 5: How Mirrorless… article that I suppose triggered your article. You could check out my post there where I also look forward.

To get the last word, unless you answer! ;), I created a separate post with my thoughts.

I had a parallel experience a few years ago at my class reunion, about 5 years ago. Everyone was using their little point and shoot cameras or their phones to take pictures, and I was the only one with a DSLR. The interesting takeaway was that everyone felt intimidated by having a large camera aimed at them, and several people mentioned this. But, later, when everyone was posting their pictures, mine were the ones that people liked the best, by far!

Hi Vinnie,

Thanks very much for taking the time to add to the discussion here. Our thoughts are certainly in good alignment. The tool that an individual uses to capture an image really comes down to their needs and what they intend on doing with the photo after they capture it. The needs of many folks are met with the image quality they get with their phones, plus they have the advantage of using one, integrated digital communication device. I think the phone manufacturers made a brilliant move when they added imaging capability to their phones. I’m certainly off-center with most people as I’ve never taken an image with my phone and most days if I’m in my office I don’t even bother to turn it on.

When I was in Greece last fall I saw very few full DSLRs in use…maybe a dozen people at day tops. Most folks were using compact cameras, tablets, and a few had bridge cameras. I didn’t see many people taking images with their phones, but that was likely because they were on a fairly expensive holiday and they perhaps wanted better quality images. Again, it all depends on individual needs.

When doing photography for my articles or for my casual use I normally pick up my Nikon 1 gear. I love the small size, handling, and I find the image quality is sufficient for most of my needs. I didn’t bother taking my D800 and FX lenses to Greece, opting for my Nikon 1 gear instead. I will be doing this for all future holidays as well…and will likely only take my D800 if I’m planning to use my Tamron 150-600 for BIF shots or if the images from that lens will be the subject of an article.

Tom

Several things need to change for the photo industry to revive. One of them is the way photographic images are consumed: most people flip through the Facebook pictures on their phones. Fewer do it on tablets. Some do it at work on their desktop computers when their bosses are not watching them (all out work times they do it on their phones). Much fewer ever print anything. Even fewer people print it large. The question: how many megapixels does one need and how many thousand bucks does one need to spend to produce a picture that would be watched on a 5 inch phone screen? So, the means of media consumption needs to evolve.

Hi Val, thanks for joining in on the discussion.

Tom

Hi, Thomas,

I always enjoy your articles. How do you manage your photo collection? Do you print them? Digital albums? Photo frame? Online albums?

I guess, great pictures need to be on some kind of display and easy access for the author or the audience. Just curious.

I used to use iPhoto and Aperture on iMac, and I am switching to Capture One and Media Pro.

Thank you,

Val

Hi Val,

I actually have very few of my images on display. The ones I do have up are printed, then mounted and laminated. The maximum trim size is usually 17″ x 22″. I often use my images in this format when I do seminars and workshops so they serve dual duty. My wife would like us to make traditional print albums of our travel images and we’ll likely do that sometime in the future. To capture holiday memories I typically put a selection of my photos into a video production that can be quickly shown to family and friends on a flat screen TV.

I don’t have any photo frames or an online digital album. I do have some images up on my main web site (along with my safety posters etc.) as gallery prints for sale. My site is terribly out of date and I need to make time to update it as I have a lot of images to add.

This may sound a bit odd…but after I capture a bunch of images and write a corresponding article I very seldom even look at those images again. Some of them may end up on my web site as gallery prints for sale, and the odd one may get printed/mounted/laminated and displayed for a time. Usually I just move on to the next photographic challenge that I’ve set for myself and grab a camera.

Tom

I don’t know you personally, but from a photography perspective, we are brothers from another mother. I have a few “big” prints and love doing slideshows of my travels or my pet, but most of my images end up stuck in Lightroom….Since most of these pictures are from photo shoots for someone else, I rarely look at them again. I take care of them in terms of backup, but that is it.

Our ‘camera mother’ would be pleased!

Tom