Is micro four thirds suitable for wildlife photography? As someone who has photographed wildlife with micro four thirds cameras for the past 10 years, I can confidently assure you that the answer is yes! Even in today’s world where full-frame is getting the most attention, there are several perks to photographing wildlife with micro four thirds cameras.

Whether you already have a micro four thirds camera and are interested in dabbling in wildlife photography, or if you are considering buying a micro four thirds camera for wildlife photography, this article will cover what you need to know.

Table of Contents

What is Micro Four Thirds?

When people ask what camera I use, it’s rare that they know what I mean by micro four thirds. The defining feature of micro four thirds cameras is that they have a “four thirds type” camera sensor, with a size of 17.3 x 13mm. (This has an aspect ratio of 4:3, hence the name).

Micro four thirds cameras are mirrorless and – other than a few exceptions like some drones – have an interchangeable lens system. Currently, OM Digital Solutions (Olympus) and Panasonic are the two primary companies that make micro four thirds cameras and lenses.

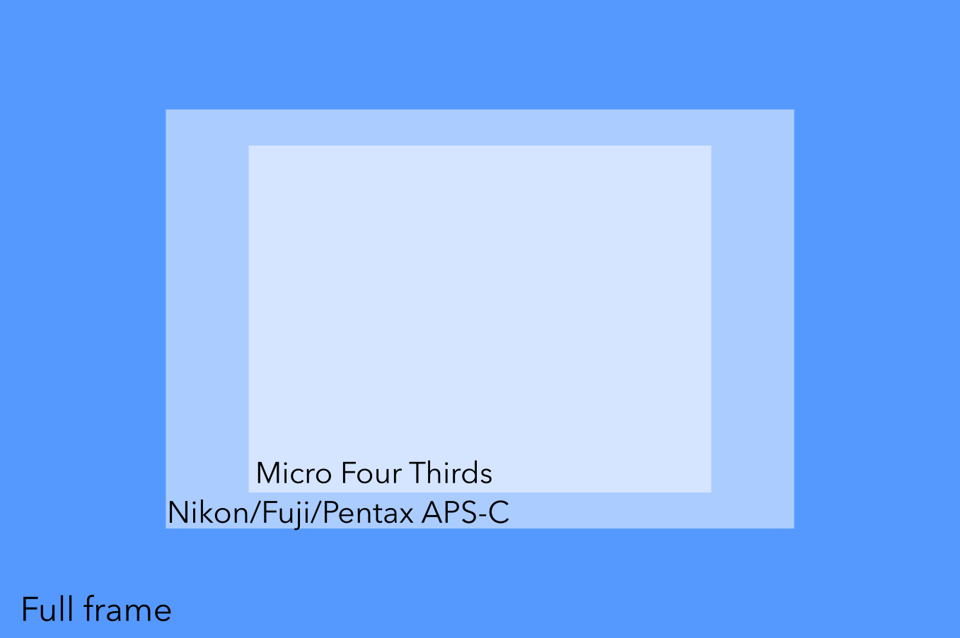

See the graphic below to see how the four thirds sensor compares to other sensor sizes.

Yes, the sensor of micro four thirds cameras is smaller, and that comes with some disadvantages. The most obvious is worse performance in low light. There’s also a 2x crop factor, which applies not just to focal length, but also to your f-stop. This makes it tougher to get a shallow depth of field with a micro four thirds camera. (For instance, to get the same look as a 50mm f/1.8 on a full-frame camera, you would need to use a 25mm f/0.9 on micro four thirds.)

So, why do I still shoot micro four thirds despite these inherent disadvantages? Do not be alarmed! It turns out the format makes up for these in several ways I will discuss in detail. They are also an excellent choice when shooting on a budget, which for many of us is a very important factor.

Micro four thirds technology has also been advancing at incredible speed. In the past 10 years, these cameras have set many of the trends that are finally being adopted by rival APS-C and full-frame cameras. (Notice how many items in our list, The Features That More Cameras Should Have, are from micro four thirds.)

Light Weight

By far the biggest advantage micro four thirds secures over all other formats is the compact body size and lightweight, yet excellent, lenses.

My Panasonic G9 weighs only 658 g, my 100-300 telephoto lens weighs 520 g, and my 60mm macro lens weighs 185 g, for a total weight of 1363 g (3.0 pounds). By comparison, a full frame camera with a 600mm lens mounted would weigh roughly 4500 g (9.9 pounds).

This lightweight setup makes shooting handheld photos easier and hiking with all my gear a breeze, which translates to better photos. I can hike long distances with all my gear without having to make the hard decision of choosing which lens to leave at home.

Less Need for a Tripod

I almost never shoot with a tripod for my wildlife photography. In fact, I have only ever owned one tripod which has been mostly broken for the past several years. Even when shooting with a telephoto lens, I find that I do not need a tripod to keep my camera steady. This is because my camera and lens are so light.

Shooting without a tripod has several advantages. First, it is one less piece of equipment to pay for. Next, tripods are big and bulky, making them inconvenient to carry. Most importantly, shooting without a tripod makes you more mobile and quicker to set your composition.

One of the most important steps in wildlife photography is controlling the few elements you can while composing your image. Tripods only further restrict you by limiting the exact position you shoot from. With the luxury to change positions as the scene changes, I’ve been able to capture photos that otherwise would have been more challenging.

The photo below is one example. In this case, the Blue-Crowned Motmot was hopping around deep in the foliage in low light. There was only a narrow hole through the vegetation through which I had a clear shot of the bird. I had to hold my camera high almost above my head. Despite not having a tripod and shooting with a shutter speed of 1/125, I was still able to stay steady enough for this shot. I never would have been able to steadily shoot this shot if I had a heavy 600mm lens on a full frame.

Landscape photographers and others may care as much about this no-tripod benefit, but it’s a lifesaver for wildlife photography. You often find yourself shooting from awkward and non-ergonomic positions to captures animals in the wild, and it helps to be as mobile as possible.

Backpack Fits All

Having small and compact gear is great for trips where I don’t know exactly what photos to expect. I can fit all my lenses, including telephotos, into my camera bag and still have room to spare for more gear and extra layers. The convenience of fitting all my gear in one mid-sized backpack is not to be understated. It makes strenuous hiking easier and is also advantageous during air travel.

It’s also helpful when I shoot in the tropics, where a downpour could occur at any second. I can throw my gear into my waterproof bag very quickly, with no need to dismount lenses.

Display Advantages

The micro four thirds cameras I’ve owned have all featured excellent displays, both in the LCD monitor and the electronic viewfinder. This is becoming standard now that mirrorless cameras are overtaking DSLRs, but I’ve been enjoying the display advantages of micro four thirds for years.

1. Electronic Viewfinders

DSLR cameras have an optical viewfinder, meaning that looking through the viewfinder is an unaltered view of the scene. On the other hand, mirrorless cameras, including micro four thirds, have a digital, electronic viewfinder. I find that having an electronic viewfinder has many advantages for a wildlife photographer.

To start, every display that’s accessible on the LCD monitor is also accessible in an electronic viewfinder. This allows me to utilize useful tools such as focus peaking, menu settings, and anything else, without taking my eye off the viewfinder.

Beyond that, I find the electronic display to be a better way of predicting how the image will ultimately look, compared to a DSLR’s optical viewfinder. The preview in my electronic viewfinder accurately reflects the exposure of the image I’m about to take, eliminating guesswork. It also allows me to review my photos to check my composition or sharpness, without taking my eye off the viewfinder.

Finally, the electronic viewfinder is great when shooting in low light, because it will brighten the display to reflect how your settings will affect the image. This makes composing and focusing easier in low light.

2. Flexible LCD Monitors

The rear LCD on most micro four thirds is fold-out and articulating, which beats the fixed LCD found on many DSLRs. This makes it easier to hold the camera at awkward angles while still seeing my composition, which I find myself doing very often as a wildlife photographer!

All of this may be familiar to mirrorless shooters of other brands, but they’re advantages that have been built into the micro four thirds system for ages. And in any case, they surpass most DSLRs in flexibility.

High Quality Video

One of the selling points of micro four thirds cameras is their video capabilities. As a wildlife photographer, I often find myself opting to take a video of an exciting scene. Micro four thirds cameras historically have prioritized video features, and newer mirrorless cameras are only now catching up.

The videos I’ve shot on my Panasonic DC-G9 are extremely crisp, even in low light. Many Panasonic micro four thirds cameras shoot 10-bit internal 4K footage, and their video performance outcompetes a lot of APS-C and even full-frame alternatives.

Lens Options

One issue with micro four thirds is that it hasn’t been around as long as some systems, so there is a smaller choice of lenses. Panasonic and Olympus are the big two lens manufacturers for micro four thirds. As for third-party options, most of them are fully manual lenses, with less than a dozen exceptions (mostly from Sigma).

That being said, the available lenses perform with excellence. All micro four thirds lenses I have shot with handle well and focus quickly. They tend to be very sharp, lightweight, and affordable.

It is worth noting that – unlike when shooting Canon or Nikon – a micro four thirds shooter can use lenses from either Panasonic or Olympus on their camera, and is not limited to lenses of their camera’s own brand.

What About Adapters?

As with most camera systems, you always have the option of adapting lenses from different manufacturers – such as Canon or Nikon – onto micro four thirds. There are even some adapters with autofocus and automatic aperture control, although they tend to be substantially more expensive, and autofocus doesn’t always work perfectly well.

That said, I haven’t tried adapting big telephoto lenses from full-frame systems onto micro four thirds. In theory, it would work reasonably well – allowing you to shoot at supertelephoto focal lengths due to the 2x crop factor of micro four thirds.

In practice, though, I find that the main advantages of micro four thirds are often lost if you intend to adapt large telephoto lenses. You suddenly have a bulkier system that may need a tripod, plus has worse autofocus performance than a native lens.

Personally, I have used adapters on my micro four thirds cameras, just not with big super telephotos. Instead, I enjoy using the Laowa 15mm f/4 wide-angle macro lens, as well as the Laowa 24mm probe lens with adapters on my micro four thirds cameras. Neither lens is available to micro four thirds shooters without an adapter.

In both, cases I have opted for the most budget friendly adapter available. Since these Laowa lenses are fully manual anyway, the cheap adapter doesn’t lose anything other than perhaps some build quality. If there are any alignment issues with it that have caused less sharpness, I’ve never noticed.

I took this photo of a parrot snake with my Laowa 15mm macro lens and a micro four thirds adapter. It is not my sharpest lens, but still produces some of my favorite images.

Focal reducing adapters are on the market for micro four thirds shooters and are a more costly means to adapt APS-C or full-frame lenses. A focal reducer includes a piece of glass which corrects for the micro four third’s crop factor.

For example, one of the most popular is the Metabones 0.64x speed booster, which allows Nikon G lenses to be used on some micro four thirds cameras. As the name implies, you multiply both the focal length and aperture of the lens by 0.64 to get the new focal length and aperture on micro four thirds. The Nikon 50mm f/1.8G would become a micro four thirds 32mm f/1.2.

However, these sorts of adapters are pricy and add weight/bulk to your setup. I tend to recommend them only if you already have a lot of lenses from an APS-C or full-frame system.

Limitations of Micro Four Thirds

Micro four thirds is not perfect for wildlife photography. The purpose of this article is not to sell you on buying a micro four thirds camera for wildlife photography, but to assure you it is a viable option. There are still limitations that must be considered.

1. Crop Factor

Because the sensor of a micro four thirds camera is significantly smaller than a full frame, the resulting image is essentially “cropped” every time you take the picture. For example, a 300mm lens on a micro four thirds is cropped to the same perspective as a 600mm lens on a full frame camera.

The 2X crop factor also affects the f-stop, as discussed earlier. For example, mimic a 300mm f/2.8 lens exactly on micro four thirds, you would need a 150mm f/1.4 (and no such micro four thirds lens exists). If you want the depth of field and bokeh of a 300mm f/2.8, you have no choice but to use full-frame.

In short, it is trickier to create a very shallow depth of field and aesthetic bokeh with a micro four thirds camera. This is not a make-or-break issue for wildlife photography, but making your subject stand out against a very blurred out background works better with a larger sensor.

In the below image of an American Crocodile, a full frame lens would have let me further blur the vegetation behind it. The 60mm f/2.8 lens here is equivalent in appearance to 120mm f/5.6 on full-frame.

That said, the 2x crop factor can be useful for placing as many pixels as possible on a distant subject in wildlife photography, so it’s not all bad.

2. Low Light Performance

Micro four thirds overall do not perform as well in low light as a full frame camera, or even APS-C. The difference is about two stops in favor of full-frame. In other words, at ISO 400 on micro four thirds, you’d get about as much noise as ISO 1600 on full-frame (all else equal).

The difference is not enormous in all cases, though. I still shoot up to at least 1600 ISO with little worry about grain ruining my photos. If I tolerate noise, I have taken usable images up to ISO 6400. To be clear, the ISO performance of micro-four thirds cameras, especially newer models, is not awful and still suitable for most situations, but larger sensors do perform better.

I shot the below image after sunset in very low light. In this image, I pushed the limits of the ISO capabilities of my Panasonic DMC-G2. Even the G2, a 12 year old camera, functions decently at high ISO. Today’s micro four thirds cameras are much better with grain.

3. Limited Telephoto Options

The most significant drawback with shooting wildlife on micro four thirds cameras is that the selection for telephoto lenses made for micro four thirds is limited. The more affordable lenses available mostly top out at 300mm, with a couple 400mm options. The higher quality glass is quite pricy too.

This is not as bad as it may sound, however. Because of the two times crop factor of micro four thirds, an image shot at 300mm on a micro four thirds camera would yield a similar photo as an image taken with a full frame camera at 600mm.

There are really only a few wide-aperture telephoto lenses for micro four thirds. The Olympus 75mm f/1.8, Panasonic 35-100mm f/2.8, and Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 are the only three obvious choices. There is also a 300mm f/4 prime lens, which is the closest to a high-end supertelephoto prime from either brand, but doesn’t let in as much light.

I don’t find this limitation to be a problem for the subjects I shoot, but photographers who specialize in distant wildlife photography may need to be more wary.

Conclusion

That sums up my thoughts on micro four thirds for wildlife photography, both good and bad (but mostly good)! If I could snap my fingers and have a full frame setup, I probably would, but there’s little to complain about micro four thirds for my wildlife photography.

The photographic quality of one’s images is not determined by the gear, but the photographer. The difference in performance between micro four thirds and other formats is not so significant to rule it out for aspiring wildlife photographers, or even professionals, depending on their needs.

Micro four thirds holds advantages over many other cameras, especially the compactness and modern feature sets. I’ve taken many photos with my micro four thirds setup that I believe would be impossible – or at least far more difficult – to capture any other way.

I hope this article has put you to ease if you had doubts about using micro four thirds for wildlife photography.

I would suggest one of the disadvantages of MFT stated, the noise at higher ISOs, in my experience can be obliterated in processing with software such as Topaz Photo AI. This effectively negates this issue in my opinion.

I think the real competitor of MFT is the mirrorless APSC format, not FF. Differences between FF and MFT are still way too pronounced for them to be direct competitors. And about the (lack of) shallow depth of field vs FF, I think it is not that big a deal. Personally I do not like backgrounds obliterated completely; why scratch our heads over composition and then melt everything but the subject into oblivion? Now there will obviously be some scenarios where MFT will be hard pressed, but that is true for all systems. Everything is after all a game of compromises.

Cheers! Great shots. Keep shooting.

MFT cameras are great for 1) portability and 2) focal reach on cheap. For wildlife they are great but not so much for other genres. I am shooting landscapes and cityscapes. The dynamic range is just barely acceptable from an APSC DSLR like the 90D which is a flagship level apsc from Canon. Especially on difficult light situations like blue hour or just after sunrise, only a full frame can handle the colors and the highlights without serious clipping. On my experience, for daytime (landscape) photos the best results comes from a pixel dense APSC like the 32mp 90D, or better, a 42mp+ full frame. For low light only full frame can do the job perfectly. The biggest drawback of MFT in terms of image quality is the ISO. And I have seen too much noise from MFT cameras even at base ISO in comparison to APSC and FF at 100% zoom or bigger prints.

What I like on MFT? 1) the lens ecosystem. I wish to had the native capability to use any APSC or FF lens on my Canon DSLR. 2) the feature proofing. MFT cameras are the best equipped for the price, at any level. Great AF, IBIS, screens and video capabilities. 3) the weight.

Thank you for your input! I agree with all your points, especially that you get the most bang for your buck with MFT.

Yep, I used to shoot birds with a G9 and really enjoyed it, especially Pre Burst.

But contrast-detect only AF cost me too many shots.

I’m a retired 66-year-old professional photographer/videographer. I have a degree in zoology. I’ve used Olympus gear since the original OM-1 days (1970s). I now shoot OM-1 + 150-400 f4.5 TC1.25X for most of my wildlife work. Sometimes I add the MC14 teleconverter. I feel that I can confidently tackle any telephoto wildlife assignment with my lightweight, agile, fast, and superb image-quality set up.

Your article fails to adequately explain one of the great strengths of the OM Systems approach to system design—processing power and computational photography.

High-megapixel full-frame systems will never be able to surpass MFT in terms of shooting speeds and frame rates (e.g. [current] ProCapture modes, sustained 120fps RAW shooting, 50fps CAF-TR ProCapture, high video frame rates such as the OM-1’s 240 fps FHD mode).

Why? Because, for example, a 50mpx (or greater) full-frame camera cannot buffer, shoot, and save-to-card, RAW images faster than, for example, a 20mpx OM-1. It’s simple physics; a bandwidth factor. This is a SIGNIFICANT advantage for fast action (e.g. BIF) wildlife photography.

When, eventually, the processing power of full-frame systems matches the current OM-1’s speed, the OM-2 (and successors) will still be way ahead of the full-frame pack, in the processing speed department, because the successor OM-x cameras will be similarly exploiting advances in microprocessor technology…they will still be saving fewer megapixels, and faster, to their cards…WITHOUT the need to crop to get a decent sized subject in the frame.

It’s not fan-boy religion. It’s physics!

As for DoF and low light noise advantages of FF. Yes, these are also science-based (physics) advantages of FF over MFT. They are simply not an issue for my work. I get fantastic bokeh through intelligent camera use. I shoot high ISO and control noise with Topaz Denoise AI.

You can see my ‘sub-optimal’ ;-) wildlife photographs and video work on FB or Instagram by searching for thelensfalcon (@thelensfalcon).

You are right it’s physics. But Sony makes the sensors and the CIOs makes politic. With MFT for wildlife only OM Systems ist absolut top with OM1 and 300/f4 and 150-400 f4,5. Panasonics AF is not good enough. That shows physics potential will not always realiesed. With OM1 and 150-400 f4,5 still the spirit of Olympus is feeling. Hope it goes on!

120 fps with CAF and continuous AE?

The A1 (50 mpix FF) shoots 4K video at 120 fps.

In my opinion MFT is a good option for wildlife photografie. The new OM1 ist very fast with AF. The Panasonic not. The prime teles are expensive. If you spend much money and you do not want heavy wight it is probably the best option!

Extrem wideangle is a problem because 7,5mm (15mm VF) LAOWA is the widest angle you can get.

For VF up to 9mm rectiliniar is available. This is about 30 degree more! Of course it is possible to stich but this is not the same:-)

There are a couple of additional telephoto options including the M.Zuiko 100-400 mm f/5-6.3 IS and the M.Zuiko 150-400 mm f/4.5 TC1.25X IS PRO. It should also be mentioned that the M.Zuiko 100-400, M.Zuiko 150-400 PRO and M.Zuiko 40-150 PRO are all compatible with M.Zuiko MC-14 and MC-20 teleconverters.

Tom

Good catch, Tom! Thank you for the addition!

Olympus/OM System M4/3 cameras and lenses are more than up to the task of professional wildlife photography.

Just check out the award winning work of professionals like…

Andy Rouse www.andyrouse.co.uk/index…?p=1000025

Petr Bambousek www.sulasula.com/en/home/

Jari Peltomaki jaripeltomaki.com/

Tom

Achieving shallow depth of field with a M4/3 camera is quite easy to do. Just use a longer focal length and position yourself from the subject appropriately. smallsensorphotography.com/shall…h-of-field

One needs to use cameras appropriately, regardless of sensor size. Suggesting that a M4/3 camera should be used with the same technique as when shooting with a full frame camera is misleading.

Tom

Thanks for the long awaited MFT article, well balanced and accurate. I’ve been using the Lumix G Vario 100-300mm on a GX7 for years, it’s a handy lightweight set which doesn’t always hit the bell but is sufficient for documenting rare birds. When you carry a scope on a tripod plus binos, weight becomes important, especially strung around your neck for miles and hours at a time.