The name Henri Cartier-Bresson does not immediately remind most people of landscape photography. It shouldn’t; he wasn’t a landscape photographer! Instead, of course, Henri Cartier-Bresson was a street photographer — arguably the founding father of the genre. However, although he rarely took photos of nature, his intimate approach to street photography still has value to people who prefer the company of grand landscapes. One technique is especially worth learning, no matter what genre of photography you do: the decisive moment.

Table of Contents

1) What is the Decisive Moment?

Sometimes, a photograph is taken at such a perfect moment that it feels as though no other point in time could express the essence of the event so perfectly. Henri Cartier-Bresson defined that as the decisive moment.

How does this work in practice? Every time that someone moves — or does anything, really — there is some point along the way which perfectly encapsulates the moment. If someone jumps, it is the moment that they are in the air. If someone catches a baseball, it is the moment their glove touches the ball. Henri Cartier-Bresson aimed to capture this exact moment in his street photos.

In street photography, one good way to capture the decisive moment is to stand in front of an interesting background and wait for something to happen. The goal is to be prepared. For example, if you point your lens at a billboard advertising cat food, it is inevitable that someone will walk their dog past the location. If you are ready to take a quick photo, you could capture an interesting and ironic image.

This is, admittedly, a simple example from someone who rarely takes street photos. Instead, I tend to photograph nature and landscapes. So, why is the decisive moment relative to such a different type of work? Quite simply, everything moves. Even landscapes, which tend to be relatively static, move and change dramatically as the day goes by. This means that you can apply the concept of the decisive moment just as easily.

2) Landscape Photography

On the recent Photography Life visit to Grand Teton National Park, our first goal was to find a good location to take sunset and sunrise photographs. I assume that this is the case for many landscape photographers — you go out in the middle of the day, search for locations, and find somewhere interesting to set up for sunset.

This process is also known as scouting, and it is one of the hallmarks of landscape photography. Every time that you visit an interesting location, even if the conditions aren’t right for taking photos, you can still lay the groundwork for a successful photograph in the future. For example, take a look at the image below:

I took this photograph at an overlook in the Grand Tetons. A lot of things are wrong with this shot. First, the light is relatively uninteresting. There aren’t any beautiful colors or unusual cloud patterns, and the entire image just feels a bit like a snapshot.

At the same time, there are some good qualities to this photograph. The mountains are beautiful, of course, and so is the river in the foreground. It’s not a bad location or a poor composition; the main problem is the light.

So, it was time to wait for better light. This sunset didn’t turn out to be very exciting — there still were no clouds in the sky — but the next day’s was very beautiful. The photograph below is the final result:

How does this relate back to the decisive moment? Although there are a few differences, the path that I followed is very similar to what Henri Cartier-Bresson described. I found a subject (my landscape) and waited for the defining moment (a good sunset). In some sense, every landscape photo is a combination of these two components.

3) The Subject and the Moment

In landscape photography, the “decisive moment” is all about light. How has the sun changed? Where is it in the sky? How do the colors look in your scene?

Landscape photography is as much about the decisive moment as is street photography. You can take a good photograph if you have an interesting subject, and you can take a good photograph if you capture the right moment. However, to take a great photograph, you need to capture an interesting subject at the right moment.

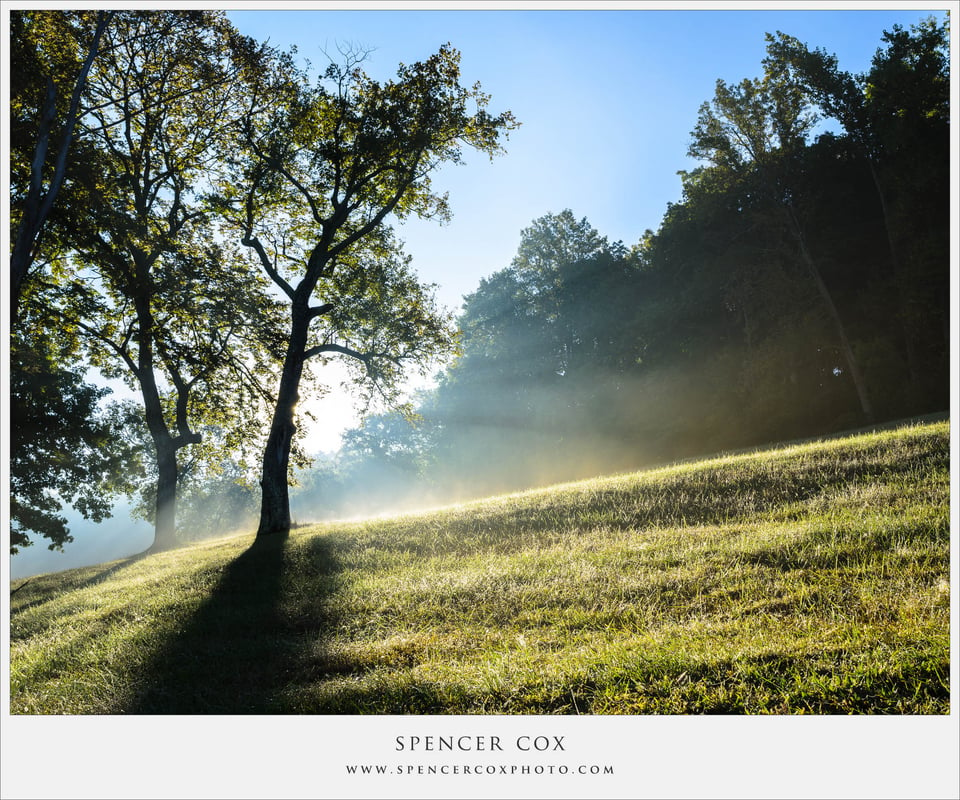

How does this look in landscape photography? Consider the photograph below:

This image was taken at a wonderful location, with dramatic lines in the foreground and interesting mountains in the distance. However, there is a crucial problem with it: the moment is completely wrong. For one, there are no clouds in the sky, but that isn’t the main issue. Instead, what bothers me about this photograph is the position of the sun: it is too high in the sky.

If I had taken the image a couple minutes earlier, there would have been a few differences. First, I could have captured the sun while it barely peaked over the distant mountains, not while it was above them. This would have shrunken the size of the sunburst in the frame, which is a big deal — currently, it just takes up too much space. Also, if the sunburst were smaller, there wouldn’t be the unusual colors around the sun, caused by a slight amount of flare. In short, the image would be much more interesting.

So, that was an example with an interesting subject taken at the wrong moment. What about the reverse? The photograph below is a good example:

Here, the light is absolutely incredible. I am a big fan of deep, dark shadows, along with dramatic clouds, so the weather here is exactly what I wanted. In other words, the moment is right — in fact, this is some of the best light that I have ever seen. So, why isn’t the final photograph one of my personal favorites?

Although I was able to find an interesting foreground, it wasn’t a stellar foreground. It was just… good. The mountains in the background are interesting, and the farm buildings aren’t bad, but they don’t have the same drama as other places I have photographed. This is what happens when the moment is right, but the subject is wrong.

It is worth noting something: the two images in this section aren’t terrible. The first one is close to being a great photo, but the sun is a bit too high. I still display the second one on my website, and it has even won a travel photography award as part of a set, so it isn’t a bad shot either. However, neither of them are world-class images by themselves.

Imagine, though, the landscape in the first photo underneath the light of the second photo. That would be an amazing shot! That’s the power of the decisive moment — good light and good landscapes work well on their own, but your goal is to combine the two in a single photo.

Finally, before moving on to the next section, it is worth mentioning that these are just my personal evaluations of the two shots, and you may feel different about their quality, either positively or negatively. The point, though, is the same — a world-class photo needs to be a combination of the right subject and the right light. In other words, it needs to capture the decisive moment.

4) Differences

The decisive moment in landscape photography is different from the decisive moment of street shots. When you are photographing people, everything moves much more quickly. It is harder to predict exactly what will happen, and it is harder still to capture it at the perfect moment.

In landscape photography, though, everything tends to change slowly. Sure, you may end up photographing a rainbow as it fades, but even then you often have a few seconds before it’s gone. Street photography, though, is impossibly quick. To capture his famous “jumping man” photo, Henri Cartier-Bresson had to be within a few milliseconds of the perfect moment. I understand that this is sometimes true in landscape photography, too. If you are photographing ocean waves or explosions of lava, you may have a fraction of a second to take the right shot. However, these are outliers for most people, not the norm.

Similarly, landscape photography has more predictable changes than does street photography. We all know when the sun will rise and set. I even have an app on my phone to calculate it, as I am sure many readers also do. Street photography isn’t random, but it is much more difficult to predict how a scene will look several minutes or hours in the future.

Finally, as I have mentioned a bit so far, landscape photography’s decisive moment typically involves a change in light. While street photographers often wait for objects in their scene to move into place, landscape photographers wait for the right light. It is a subtle difference, but it means that landscape photographers have the ability to return to the same spot — even several years in the future — and capture exactly the image they want.

Despite all these differences, though, the decisive moment is just as important in landscape photography as in street photography. You may not have to capture the exact fraction of a second that someone jumps in the air, but you will need to plan how to spend your time photographing good light before it changes.

5) Conclusion

Perhaps it will help to think of your landscape photography as capturing the decisive moment, much in the same way as street photographers do. Ultimately, the goal is to maximize the amount of time that you spend in amazing locations under the right conditions. This may sound intuitive, but it is the real secret to successful landscape photography.

This is very amazing article…

I am fairly new to photography, and am learning all the time. Just starting to consider landscape photography, I now have more food for thought as I plan what I want to do. Thank you for this excellent article!

Glad that you found it useful! I think you will find that landscape photography is worth trying out :)

Previsualization, scouting an area, knowing where and when to be there for the right conditions. No ‘decisive moment’ other than the one you planned.

Yep, that’s the goal!

Thanks for putting a name to something we all try to capture—The Decisive Moment.

There is a location that I return to frequently. When the conditions are right it’s a special place to get an amazing image. When the light is otherwise, it’s just an ordinary location.

Some of the images captured at this location can be predicted well in advance (rising or setting moon/sun/stars/planets) while others can only be anticipated based on the weather (e.g., lightning, clouds, snow, reflective pools from recent rain, etc.).

Perhaps one of these days I’ll put together all my images showing the many moods and Decisive Moments of this special place.

Thank you, David! There can be many decisive moments at a particular landscape, depending upon a change in conditions. I wish you the best in capturing them all :)

I think that comparing the considered slow pace of landscape photography, to the immediacy and urgency of street photography is quite a long bow to draw

For many photos, I would agree with you. But, what about Galen Rowell’s famous photo of the Potala Palace? He had to run at a frantic pace to capture the rainbow before it faded. The same is true for Ansel Adams’s “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico,” which is a story I am sure you have heard. These are not outliers — they are two of the most famous photos of all time. Sometimes, landscape photographers have the luxury of waiting for the light. Sometimes, the right moment fades away in an instant.

Conceptually speaking those examples, and others along the same lines in the landscape discipline, don’t have the same urgency at all. I’m sure there were times when Cartier-Bresson took a more deliberate approach as well, but the term ‘Decisive Moment’, speaks of an otherwise elusive moment in street photography, perhaps never to occur again. The moon in Adams’ shot would have been there at the same spot the following night, albeit with subtle differences perhaps. In the end though, it’s just the internet.

Nice shots btw

Thank you, Byron! I see what you’re saying. I always have thought of the decisive moment as photographing the exact second that captures the essence of a landscape, or a scene on the street. So, I see no problem if that scene happens to repeat itself, since there is still a single moment that encapsulates exactly the feeling I want to convey. However, by your definition, I agree wholeheartedly.

Piloting and aircraft is sometimes described as “Hours of boredom followed by moments of pure terror”. Landscape photography can be hours of waiting/planning followed by minutes to even seconds of opportunity.

What I think is the decisive moment might not be the decision moment for the people who buy your photos. For example, you don’t like that picture in the sand desert but I like it very much.

I also like that one. The stark contrast and the beautiful lines created by the long shadows is what makes the photo. Had the sun dipped below the mountain, the exposure would have been longer and we could see even more details in the shadows. And then perhaps the drama and mystery would have lessened. Would be nice to see both versions.

I thought it was great as well. I loved the interplay of light and shadow and the texture of the dunes and the sunburst.

Thank you, Z! I like the photo too — I just wish that the sun were slightly lower, barely peeking over the mountain, to have a smaller sunburst.

Hi Spencer, even I liked the exposure in the sand part. If starburst is the only concern, can you not play with it in PP?

Yet another well thought out and well put down essay. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Very glad that you enjoyed it!

I wish you would include a quote from Bresson, where he talks about the decisive moment.

The Decisive Moment was the name of the English translation of Cartier-Bresson’s book. The original quote — not his — dates back to Cardinal de Retz in the 17th century: “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.”

This is how Henri Cartier-Bresson described it himself:

“To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression.”

Hey Spencer,

Great article. I didn’t know there was a name for this. All I know is since I wanted more story in my landscape pictures I have to get up early hahaha.

That’s definitely one of the hardest parts about landscape photography :)

I think the first photograph is stunning, with its innocent, calming demeanor. But I wish it was possible to position your camera behind the river so the river leads a viewer right through the foreground to the horizon. I am curious to see that that would look like!

Thank you, Clement! We did try a few different camera positions, including the one that you mentioned, but the view we had in mind wasn’t accessible. I’m sure that it would have been a great angle!