You can easily fill a backpack (or even the trunk of a car) with a landscape photography kit. Cameras and lenses only scratch the surface – there’s an overwhelming number of other accessories out there. This article breaks down what’s available and explains exactly what a landscape photographer really needs.

This article isn’t meant to be a review of any specific product or company. Instead, it covers all the camera gear and accessories that are commonly used for landscape photography, along with my thoughts on whether or not they’re necessary in the first place.

Here’s how I’ll be ranking the usefulness of each type of gear:

- 1/4: Rarely worth getting

- 2/4: Can be useful

- 3/4: Very useful

- 4/4: Must buy!

This article only covers “ordinary” landscape photography rather than Milky Way photography, which I have covered in a separate article here.

Table of Contents

Camera (4/4)

A camera is obviously necessary for photographing landscapes, but which one? Unless you’re printing massive images, landscape photography isn’t that demanding of a genre. You can get away with cheaper cameras without anyone noticing, and you can even use image blending techniques like panoramas and averaging to squeeze more image quality out of them. I love 45 megapixel full-frame cameras (or 100 megapixel medium format cameras) as much as anyone, but you can easily take good landscape shots without them.

I recommend at least a micro four-thirds camera sensor with 16 megapixels or more. A 24 megapixel aps-c sensor is an even better target, and a 30+ megapixel full frame camera or larger is the crème de la crème. There are some potentially helpful features found on advanced cameras like sensor shift or focus stacking that can make landscape photography easier, but again, none of them are strictly necessary. If you have a bigger budget, our best landscape photography cameras article may help you decide. But chances are that whatever camera you already have is enough, so long as it has interchangeable lenses.

Second Camera (3/4)

I never leave on a landscape photography trip without a second camera, but I generally make sure it’s a lightweight (even pocketable) camera that is as easy as possible to carry along. Every camera dies eventually, and you don’t want to be empty-handed if yours stops working in the middle of a shoot. Even a phone can suffice as a backup if you’re happy with yours. Otherwise, pack away a small camera with a built-in lens like the Fuji X100V, Ricoh GR III, or Sony RX-100. I use the Nikon Coolpix A for this purpose – a tiny, discontinued DX camera with an 18mm lens (28mm equivalent).

Drone (2/4)

In recent years, I’ve taken some of my favorite photos with my drone, the DJI Mavic Pro 2. A similar but less expensive option is the newer DJI Air 2S, which also has a 1-inch type sensor – what I consider the minimum for high-quality landscape photography. Drones aren’t universally loved, and they’re also prohibited in many of the places where they’d make for great photos, like a lot of National Parks (rightly so in most cases). But there are still plenty of locations where drone photography is legal and unobtrusive, with great scenery that looks amazing from the air. They’re hardly a necessity but can lead to some great shots that can’t be captured any other way.

Lenses

Wide Angle Lens (3/4)

Wide angle lenses (anything about 24mm and wider) are by far the most popular type of lens for landscape photography. But sometimes photographers are a bit overzealous about them. “Beautiful scene + capture as much as possible in one shot” is not always a recipe for great photos. A wide angle lens is very useful for landscape photography, especially if you want to exaggerate the foreground, but it’s not the only way to get good results.

Normal Lens (3/4)

I’d categorize a “normal lens” as something in the range from about 28mm to 70mm full-frame equivalent. These are a bit more maligned for landscape photography as static or boring focal lengths. And it’s true that they don’t give you the exaggerated foregrounds of a wide-angle nor the subject isolation of a telephoto. But they also feel very natural and unforced. The longer I do landscape photography, the more I gravitate to this range of focal lengths.

Telephoto Lens (3/4)

Everyone knows that telephoto lenses are good for wildlife and sports photography, but it’s also becoming more common to see them used for capturing distant landscapes. It seems like every month I see a new article on popular photography websites about using telephoto lenses for landscape photography. There are a couple such articles on Photography Life, too, here and here. Like wide angles and normal lenses, you don’t need a telephoto to take good landscape photos, but it’s very useful.

I recommend that landscape photographers have a wide, normal, and telephoto lens if possible, but any of the three is sufficient to start. I spent a couple years shooting with nothing but a 105mm prime and still consider those photos to be among my favorite landscape shots.

Tripod (4/4)

There are some landscape photographers who say you don’t need a tripod any more. I’d say to ignore them. Sure, high ISO performance is better than it’s ever been, and some specialized post-processing techniques like image averaging can potentially salvage handheld shots even in low light. But tripods do more than just maximize image quality. They also make it easier to use techniques like panoramas and HDR. Any my favorite reason for using them, even in bright daylight, is to make small and careful adjustments to my composition.

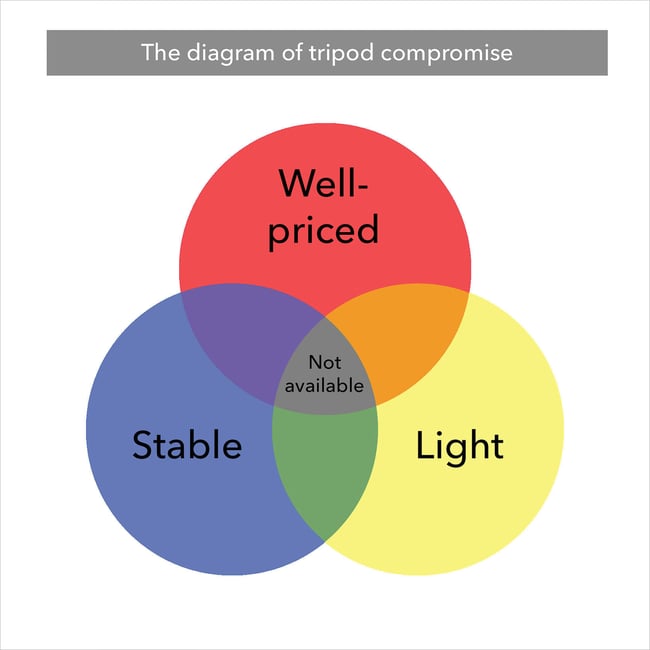

Tripods can be heavy and expensive, and some of them aren’t very stable, either. I always like showing this diagram:

But the truth is that tripods are getting better and better these days. You can find some sub-$200 carbon fiber tripods that are fairly stable and well-built. An earlier guide of ours goes into detail on getting a good tripod for landscape photography – but the important thing is to get one in the first place.

Tripod Head (4/4)

I consider a ball head and a geared head to be the two best types for landscape photography. Ball heads are smaller, lighter, and less expensive while being just as stable. Geared heads are nice for making very fine adjustments to your composition and are preferable if weight and cost aren’t major concerns. Regardless of which type you pick, you can’t use a tripod without a head, so find one that works for you.

L-Bracket (3/4)

To attach your camera to a tripod, it’s common to put a small lens plate on the bottom of the camera. However, this can make it awkward to take vertical photos with most tripod heads. The solution is to use an L-bracket instead of a small plate. These brackets hug the camera and allow you to attach it vertically just as easily as horizontally.

Panorama Nodal Slide (2/4)

If you like shooting panoramas, especially with a wide angle lens, an important tripod accessory is a nodal slide. It allows you to slide the camera forward and backward on your tripod head so that the “nodal point” of your camera system is exactly centered over the tripod head. When the nodal point is centered, you won’t get any parallax issues in your panorama (where the relative position of objects in the frame changes as you take each photo in the panorama).

I know that sounds really obscure, but dedicated panorama photographers will find these invaluable. You’ll simply have a much easier time aligning your panoramic photos in post-production if you used a nodal slide to center your camera system ahead of time. But it’s also a bit of a special case that doesn’t apply if you don’t shoot a lot of wide-angle panoramas, so I’m not rating it any higher than “can be useful.”

Tripod Leveling Base (2/4)

Normally, unless you’re on totally flat ground, it’s common for your tripod to be slightly tilted to one side or another. Even with a bubble level on the tripod, it can be a slow process to get the legs to be completely level. This isn’t much of a problem for ordinary landscape photography, but it can throw a multi-image panorama off-kilter.

The usual way to fix this problem is with a leveling base for your tripod. Leveling bases go directly underneath the tripod head, and they have a few degrees of motion in each direction to allow your tripod head to be completely level even if the tripod legs aren’t. This way, you can rotate the tripod head to take multi-image panoramas without introducing a major tilt to your shots. If you shoot a lot of panoramas, I recommend picking up a leveling base.

Spiked/Claw Tripod Feet (2/4)

Another popular tripod accessory is a replacement for the standard rubber tripod feet. The most common replacement is for spiked feet, which are better at digging into sand and sticking there. Another option is for clawed feet, which are meant to grip well on wet or icy rocks.

I have some spiked tripod feet that I will occasionally bring along if I’m expecting to do a lot of seascape photography from a sandy beach. They’re nice to have but not critical.

Filters

Polarizer (4/4)

I think every landscape photographer needs a polarizing filter. By minimizing most types of reflections, they tend to improve the look of foliage and water substantially. They can also darken and saturate the sky – something that’s often doable in post-processing but still easier in the field.

ND Filter (2/4)

Almost everyone agrees that polarizers are useful for landscape photography and difficult to replicate in post-processing. There’s more division when it comes to other types of filters, particularly neutral-density (ND) filters and graduated ND filters.

ND filters are dark, neutral colored filters that allow you to use longer shutter speeds if desired. They can theoretically be replicated in post-processing by taking multiple photos with shorter exposures and averaging them in software like Photoshop.

I rarely find myself in a situation where either is necessary, to be frank. I’m usually happy with the shutter speeds I can get in-camera and don’t need extra motion blur from a long exposure. I tend to bring an ND filter along anyway but find myself using it a lot less than I’d expect.

Graduated ND Filter (2/4)

A graduated ND filter is simply a filter which is dark on one end and clear on the other, smoothly transitioning from one side to the other in a gradient. The idea is that the graduated filter can be aligned to darken the sky in your photo while leaving the ground untouched (thus helping avoid overexposed highlights in the sky).

It’s possible to simulate graduated NDs in post-processing with HDR or other image blending techniques. But there are still plenty of photographers who would rather get everything right in a single in-camera exposure, or who simply prefer the look of a graduated filter over HDR.

As with regular ND filters, I carry along a graduated filter but rarely use it. Nor do I often use HDR – not because I have anything against it, but just because I don’t end up photographing a lot of landscapes which need more dynamic range than my sensor is capable of with proper exposure. But some landscape photographers may consider these (and regular NDs) to be far more essential. It depends on your needs.

UV Filter (2/4)

I’m not a fan of UV filters (AKA clear filters or protective filters), particularly because of the additional flare that most of them add when the sun is in the frame. However, I still consider them a potentially useful accessory for landscape photography.

In windy and sandy conditions, it’s possible for the front element of your lens to get scratched even if you’re doing everything else right. A UV filter can take that damage instead. Also, many high-end UV filters these days have water-repelling coatings, while a lot of lenses don’t. If you’re planning to do waterfall or oceanside photography, a UV filter can make it easier to keep your photos free from water droplets.

Other Filters (1/4)

There are almost limitless types of other filters that you can use in photography. I don’t consider any of them to be very useful for landscape photography, at least when shooting digital. (Film photographers may wish to look into some color corrective filters.)

One minor exception is if you want to take exposing to the right to the absolute extreme. If you use a cc30m, cc30p, cc40m, or cc40p magenta filter, you’ll tone down the green color channel of your camera sensor, which tends to clip sooner than the red or blue channels. Technically you can get about 1/2 stop better dynamic range when using one of these filters on your camera at base ISO. I don’t do this or recommend it in general, but it’s worth knowing the effect exists.

Lightning Trigger (2/4)

If you want to photograph lightning, it may seem like a good idea to get a specialized lightning trigger from Miops or similar. And these triggers do work well if that’s your plan. But lightning photography is not something I recommend in general, for obvious reasons – and even if you do want to photograph lightning, a dedicated trigger isn’t necessary.

I actually have a Miops trigger but usually forget it at home. I took the only good lightning photo in my portfolio using the classic “timelapse method” where I set my camera to take photos on an interval and simply reviewed the pictures for lightning later.

Handheld Meter (1/4)

There are different schools of thought on metering in the digital world. I’m of the opinion that the in-camera meter is the only one you need, especially if you’re supplementing it with the camera’s blinkies or histogram. I’ve never met a scene where I’d have gotten better results with an external meter, at least on a digital camera.

Remote Shutter Release (2/4 or 3/4 depending on camera)

The most basic use for a remote shutter release is to allow you to use exposures longer than the normal 30 second limit on most cameras. Another major reason is to reduce camera shake caused by pressing down the shutter button.

However, many cameras these days allow longer than 30 second exposures (such as any Nikon camera with the “Time” exposure mode). And it’s just as easy to reduce camera shake with a self-timer or exposure delay mode, assuming you don’t mind waiting two seconds for the photo to be taken.

Remote shutter releases can still be useful, but I find myself bringing one along less and less these days – in fact, not at all in the past couple years. I know that a lot of landscape photographers would consider these a critical part of the kit, though. Take that as you will.

(Note that there are also much more advanced remote shutter releases such as intervalometers and even camera controllers that have many more features. I consider these to have a similar rating of 2/4 or 3/4 – not strictly necessary but potentially useful depending on your needs.)

Extra Batteries and Memory Cards (4/4)

I always recommend bringing along at least two extra camera batteries and an extra memory card with more capacity than you think you’d need. Personally, I’ve forgotten my memory card at home enough times that I now keep a spare in my car. You won’t be able to take any pictures without these necessities, and they don’t weigh much, so bring an extra!

Waterproof Memory Card Case (3/4)

Any sort of waterproof memory card case does the trick. The lighter the better if you’re planning to hike with it.

USB Battery Charger & External Battery Pack (3/4)

I’ve found that the best way to keep my camera and phone charged in the backcountry is with a generic battery pack (something with at least 10,000 mAh) plus a USB charger specific to my camera batteries. At the end of the day, I’ll plug the USB charger into the battery pack and recharge any empty batteries. One 10,000 mAh pack is equivalent to about four Nikon EN-EL15c batteries. My preferred battery pack is 20,000 mAh and lasts for ages.

Rain Cover (2/4)

Although I give rain covers a 2/4 rating, it really depends on what environments you shoot in. If you’re constantly photographing waterfalls or taking pictures during monsoons, a rain cover may be essential – whereas other landscape photographers may never need one at all. I personally haven’t bought one, but it would have been useful for me at least once, when I temporarily killed my Nikon D800e in a rainstorm several years ago (it was working fine again an hour later).

Backpack (4/4)

The best way to carry a camera for landscape photography – particularly with a tripod – is a backpack. Not just any backpack will do. The vast majority of dedicated camera backpacks are uncomfortable for long hikes and not at all designed to carry weight optimally. Even “hiking” camera bags like those from F-Stop Gear and Shimoda are what I’d consider the bare minimum for long hikes.

A much better alternative is to find a dedicated hiking backpack from a company like Gregory or Osprey and simply use it to carry camera gear. Some photographers complain that these bags make it hard to access camera equipment fast, but that’s just not true of many of them. Go to an outdoors store in person and look through the hiking packs. I’m sure you’ll find at least one that has easy access points. Your back will thank you.

Grab Bag (3/4)

When I’m doing landscape photography out of a car, I find that it helps to have a dedicated grab bag in the trunk for little essentials. For example, I may throw my extra jacket, filter kit, USB charger, and a bag of batteries into the grab bag. These are all things that I want to have accessible during the trip, but not things that I need to carry on my back every time I go on a short hike. It also helps for organization and spreading out while I travel. An ordinary canvas or cloth bag works well here.

Sensor Cleaning Kit (4/4)

I’ve found that my camera sensor gets dirty at the most inopportune times. And now that I’m using a mirrorless camera rather than a DSLR, it seems to happen a bit more often than usual (though it’s also a bit easier to clean).

Usually, a rocket blower is sufficient to clear pesky dust particles from my camera sensor. If not, I’ll either use a sensor gel stick or a wet cleaning option (or both) depending on how bad the dust is. While you can generally remove dust specks in post-processing without too much difficulty, it’s a big annoyance if you have to do so for dozens or hundreds of photos from a trip.

Lens Cloth and Cleaning Kit (4/4)

Lenses get dusty and dirty sooner than cameras, and while it’s not as big of an issue, it can still lead to some unwanted effects. That’s especially true if you’re taking pictures in rainy conditions or near a waterfall, when there’s no avoiding some water droplets on your lens. Bring an absorbent lens cloth (I like to use a microfiber towel) to clear the way.

Solar Charger (1/4)

For charging camera batteries or your phone in the middle of nowhere, a solar charger seems like a great solution. And maybe it is under certain circumstances. But I find that a pre-charged battery pack weighs less, packs smaller, and charges enough to easily last a week without issue. I bought a solar charger years ago and have never needed it. Maybe if I ever go on a month-long outing in the wilderness (which I won’t) I’ll change my mind.

Specialized Apps (3/4)

There are apps available these days for almost anything you can think of in photography. My favorites for landscapes are OptimumCS for hyperfocal distance calculations, Photopills for tracking the sun, and The Photographer’s Ephemeris for planning my shoots. You should also look into various weather apps and, if you’re planning to fly a drone, a map to figure out legal restrictions.

GPS Camera Attachment (2/4)

Some photographers like knowing where they took a particular landscape photo, either for the sake of memory or just to make it easier to return there in the future. I’ve never cared too much about that personally, but if you do, there are GPS attachments available for most cameras that will attach the location to each photo’s metadata.

While a GPS attachment for a camera isn’t something I care much about, a GPS for navigation is essential. You’ve got to know where you’re going! I find that the GPS on my phone or Garmin watch usually does all I need, especially in combination with maps like All Trails, Gaia, or even a downloaded Google Map. This applies both to hiking and driving in the middle of nowhere without cell coverage. Make sure to have a map downloaded or printed ahead of time, and a GPS to navigate it.

Other Camping/Hiking Equipment (4/4)

This isn’t an article about hiking gear (I’ll work on one of those at some point) but suffice to say that it’s just as important as all the camera equipment above, if not more so. You need proper clothing, food, and shelter for where you’re going, plus first-aid and safety equipment. Even if you’re only going out on a short hike, don’t skimp. My rule (learned after some scarily close calls) is to consider what would happen if you broke a leg in the middle of the hike; make sure you have enough gear or are in a popular enough area that you would be safe even in such a situation.

Computer, Display, and Printing Equipment

As much as I love the field side of landscape photography, the studio side is also of utmost importance. To edit and organize your photos, you need some sort of software like Lightroom, Capture One, DxO PhotoLab, ON1, and so on, plus a fast enough computer to run them. Equally important is a good computer monitor (I recommend an IPS monitor which covers the Adobe RGB gamut) and calibration equipment so you know you’re editing the correct colors. Then there’s the whole printing side of things – a world of its own that you can either do yourself or outsource to a lab. As much as this article is geared toward the field side of things, you still need to think about what you’re going to do with your photos after you’ve taken them.

Milky Way Photography Equipment

This article is getting long enough already, but I have a separate article that goes into my recommended equipment for Milky Way photography! There are enough differences compared to “regular” landscape photography that it needed a full article of its own.

I hope you found this guide to be useful, and if there’s anything I missed, let me know in the comments below. Personally, I bring along the equipment I rate as 4/4 on every landscape trip I take, plus most (or all) of the 3/4 equipment and often some 2/4 gear as well. But every landscape photography outing is different, and so is every photographer, so feel free to modify this list as needed for your own work.

One more dumb one – a trash bag. Makes a good rain cover for the bag or the human (emergency poncho), can serve as a place to set camera gear on, on muddy ground or to kneel or lie on, for low angle shots on muddy ground.

Also, sadly, sometimes you need it for it’s intended purpose – to haul away crap that someone else left on a trail. 🤬

Great topic with excellent advice. The only nit ai have is going with a dedicated backpack company to carry your equipment. There are now a number of companies that make very comfortable backpacks that are created with photographers in mind (i.e. Shimoda, F-Stop, etc.) I find Shimoda bags (no, I’m not in any way associated with the company) very comfortable for all-day use and they have numerous options. They are pricey, though. Thanks for the article, great read.

Thanks David. I like both F-Stop and Shimoda just fine (you may have missed my mention of them in this article). I’ve actually reviewed a bag from both of them before on Photography Life! And though I think they’re good for short hikes or sub-25-pound bags (about 11 kg and less), I find that dedicated hiking packs are far, far better otherwise.

I’m not referring to any random backpack that you might find at an outdoor gear store. Lots of those are no more comfortable than a basic camera backpack. Rather, there are some companies which make technical packs intended for multi-day hiking trips. Some backpacking websites go into much more detail than I can, but I strongly suggest testing those in person with 50+ lb loads (most camping stores will have people who can help you do that) and getting whatever is comfiest and has the best camera gear access. Not that you’ll hopefully be carrying 50 lbs as a photographer, but what’s comfortable there will feel like carrying a cloud at 30 lbs or less.

Spencer,

Excellent article. “Long time reader first time poster” here. I’m curious: What do you use to keep your cameras, lens, etc. safe and secure inside a normal hiking pack?

I’m also a fan of Gregory packs for both day hikes and overnights. But not quite sure what the right solution for padding and waterproofing is. (I’ve tried a dry sack with some t shirts stuffed inside it, but feels like there’s probably a better solution out there.)

Thanks in advance.

Matt

Sure thing. I use an insert from Shimoda to hold the camera gear safely. F-Stop Gear makes similar inserts – bulkier but a bit more padded. These hold the camera gear in the right spot for quick access via my pack’s large rear zipper. Not sure how I’d rearrange things if my pack were top-load only.

For waterproofing, I just use the backpack’s own rain cover if it starts to rain. I’ve never had any substantial amount of water reach the interior of the bag at that point.

Hello Spencer,

Appreciate very much the content that you and Nasim put out! Can you recommend a good lab or two for outsourcing printing of some “keepers” at 8×10 or 11×14? Also, maybe a few words about the proper procedures for doing so. Thanks!

Thanks Dave, I don’t have a ton of experience outsourcing to print labs, but from what I’ve seen, all the big ones do a good job. Mpix and Bayphoto are the ones that come to mind offhand. Bayphoto is where I tend to get prints done in the rare case that I want some unusual print, like on metal or wood.

The simplest way to get good colors that match those on your (calibrated) computer monitor is to export to sRGB and select the print lab’s “color correction” option if they have one.

A more complex method that is usually only feasible if you’re printing from home is to export images to the color space of your ink+paper combo, generally in Photoshop, and do slight manual color fixes after that.

I’ve written a bit about both methods before, found in section 7.2 of this article: photographylife.com/image-quality

Thanks Spencer, I will check your article and both labs. On both of my Nikon cameras I have selected under the Photo Shooting Menu: Color space: Adobe RGB. Assume that has no effect on exporting to sRGB for printing?

If you’re shooting in raw, it has no effect on anything other than very slightly changing the appearance of the image on your camera screen! Raw photos are not converted to the color space selected in camera.

If you’re using Lightroom with those raw photos, your working space is a color space similar to ProPhoto RGB, no matter what you selected in the camera. No way to change that in Lightroom’s settings, either. Only upon export does sRGB (or anything else) actually get baked into the file.

Hi Spencer,

I read the below quote in a 2018 PL article. I’m not splitting hairs but I am wondering if there are less expensive, good quality, non UV filters that may provide protection and better pass-through ability?

Thanks for another informative article.

“UV / Protective Filters

Let’s get UV filters out of the way – indeed, unless you are using a film camera, they are completely useless for the task of blocking UV. That’s already done by your sensor filter stack, which contains a UV blocking filter. Today, UV filters are only used as “protective” filters, for the purpose of protecting your lenses against damage.”

Sure thing. UV filters are the least expensive high-quality filters that provide some protection. They let through something like 99% of the light, so you won’t notice any light loss when using them. They go by other names like clear filter, haze filter, and protective filter, too. But it’s all basically the same thing.

That said, I use a polarizing filter so often that I don’t bother with UV filters. I think I only have one and almost never use it.

Thank you

How can I disagree with you, Spencer? It seems you took a look at my backpack and my grab bag. I always grab a second small “urban” tripod, a front light and a flash.

The grab bag is the key to all my road trips. Amazing how much easier it makes things.

Great article and fantastic photos. Thanks.

Do you use a sensor gel stick on Z6/Z7 without any problems? – as far as I remember Nikon recommended not trying to clean the sensor on their mirrorless Z cameras (not sure if it is due to IBIS?).

Yes, I use a sensor gel stick all the time on my Z6 and Z7. Never had any issues with it. It’s not sticky enough to wobble the sensor, unless maybe you’re intentionally trying to damage the camera.

Thanks, really nice to know. Haven’t dared to do it yet, so nice to know that it is possible.

Where to get these gel sticks?

Photography Life is the only site that sells the official ones, and we’re out of stock right now unfortunately. You could risk it with a knockoff on Amazon in the meantime, or wait until we get some more in stock, most likely later this year.

Thank you! It would be helpful to have a notification when these are available.

Will do, I’ll make sure to post about it when they’re back in stock.

Thank you! If you meet someone in the business from Wisconsin someday, preferably from Cambridge or Stoughton, please tip them about my dream to sell images to Norwegian/Americans from my region: stock.adobe.com/no/co…C3%98yvind

Great article, Spencer. The only area where I have a differing opinion is on UV filters which I have on every lens for protection against drops. I have had two drops of my D750 where the camera/lens combo was saved by the filter, so for me, a UV filter is a necessity. On another note, I’m wandering which USB charger you’d recommend for the En-El 15 batteries? Thank you.

Thanks, HMS! Everyone has a different opinion on UV filters. Personally I find a lens hood to be sufficiently protective for my needs, except in sandy/windy conditions. Certainly nothing wrong with using UV filters if you prefer them.

I use this USB charger but there are many similar ones: www.amazon.com/Wasab…olife0c-20

It’s from a company called Wasabi and actually comes with two off-brand Nikon batteries, which frankly is a steal for the price. But be aware that the two included batteries probably don’t work on the Nikon Z6 II or Z7 II. (The ones I bought don’t, but I bought them a couple years ago – Wasabi may have updated their batteries since then. They work fine on my older Z6 and Z7.)

While not for everyone or every occasion a very short set of light tripod legs is quite useful for low perspectives. Along the lines of 15″ max height and under a pound, headless. Screw your usual head into the short legs. Can compress down so an easy fit in backpack. Likely another 2/4 item.

Great suggestion, thanks Charles! I know several photographers who have multiple tripods for different situations – hiking, car travel, international travel, etc.

Spencer, excellent point about backpacks. I just use a Gregory 65L backpack, which is more than enough for camera gear (and I can use it for backpacking!).

Regarding image sensor cleaning kits, how good is the automated sensor cleaning of different brands? I have a Z6 and Z7II and as a SOP, I use the “clean sensor” menu option every time I swap a lens. The Z7II seems to do so in much less time than the Z6, but I have not measured how effective this is. I wonder about the same option on Sony, Canon etc.

Hey, we have the same backpack! I love it, one of my all-time favorite pieces of gear.

At least on Nikon, the automatic sensor cleaning is pretty hit-or-miss. I find that it sometimes manages to remove dust, but other times just shifts it to someplace else on the sensor or doesn’t move it at all. Sony’s and Canon’s are similarly effective (or ineffective as the case may be). They’re better than nothing, but I still end up needing to manually clean the sensor with some frequency.

Yes, what I especially like about this backpack is that the main compartment can also be accessed by unzipping from the front!

I have been petrified to clean the sensor myself other than using a blower. Any recommendations on cleaning kits?

Regarding battery packs – after 3-4 weeks trekking in the Himalaya a few years back, I discovered that battery packs run out (and sometimes sooner than you expect in cold conditions), and a good solar panel can come in handy to charge the battery pack and your gear – I borrowed one from another trekker. When traveling internationally you are also limited in how powerful a battery pack you are allowed to carry on a plane. And there isn’t much point carrying more than one because of weight. You can buy battery packs that also come with solar panels that they claim can be used to charge the pack, but the one I got did not work well for me.

Sony sensors are like magnets to dust, neither automated cleaning or blower helps much. Hope they’ll innovate anti-static sensors soon!

Excellent article Spencer. Another useful item for panoramas might also be a leveling base. It is probably best classified in the “can be useful” category since the same can be achieved by just adjusting the tripod legs for level. However, I have found it makes things a little easier and less fiddly on uneven ground.

Great addition, thanks David. I just added a couple paragraphs about leveling bases. They’re a big help for panoramas.