If you’re first starting out in landscape photography, you probably have a lot of questions. It isn’t always an intuitive field, and not everyone finds a connection to it. That said, landscape photography is such a rewarding pursuit that many photographers want to learn more tips and techniques to practice it as well as possible. In this article, I’ll share some of my top landscape photography tips for beginners, including some suggestions that might fly in the face of what you’ve heard before. Hopefully, you learn something that helps you out along the way.

Table of Contents

1. Don’t Follow the Rules of Composition

Some photographers say that there are rules of composition in landscape photography. Are they correct? Don’t take everything at face value.

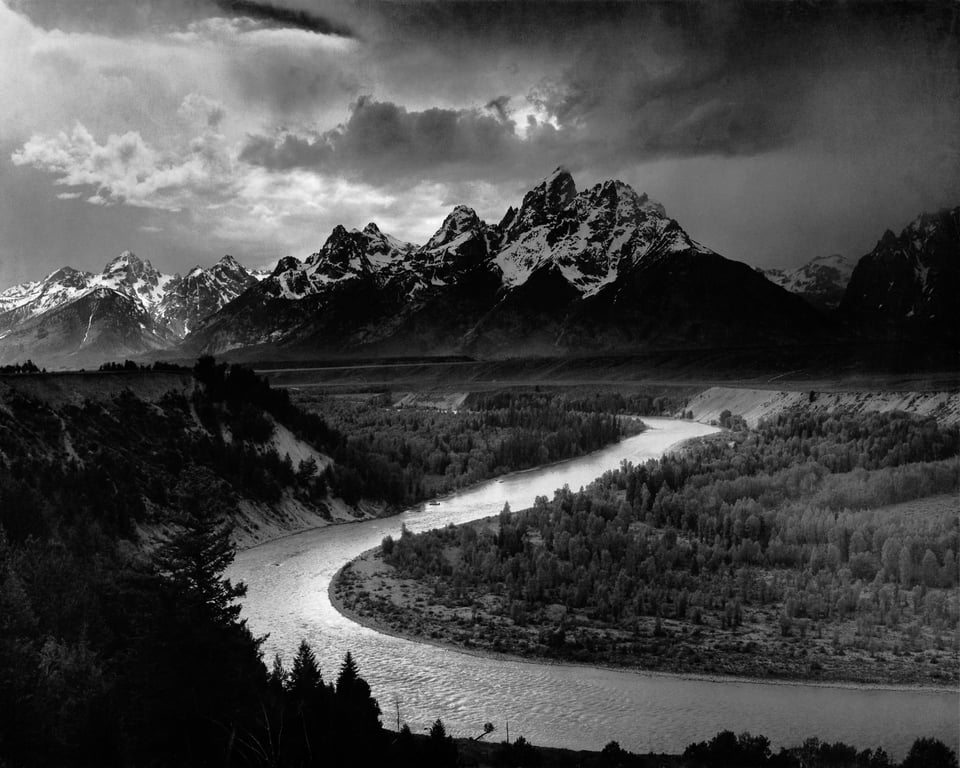

When creativity is involved, it is easy to fall back on basic tips and suggestions that simplify things. But the problem with many of these tips is that they oversimplify a remarkably complex process. Even the famous rule of thirds does this, distilling a deeply personal process down into an impersonal grid. Take a look at the work of a master photographer like Ansel Adams or Galen Rowell — or photos by any photographer you like. Chances are good that they compose their photos based upon what looks good, not upon a pre-conceived formula.

It’s not just the rule of thirds, either. Although that is the best-known “rule,” some others pop up from time to time. So, to be clear: All of this applies equally to every such rule and special grid of composition. The golden ratio, dynamic symmetry, the rule of triangles, and so on… These are cookie-cutter formulas that sound fine on paper, and might work as basic tips for beginners, but have no relevance for advanced creative photography.

That’s because composition should change vastly from photo to photo. It strongly depends upon the scene in front of you, as well as your personal style as a photographer.

Think about a practical example. For one photo, you might want to capture the chaos and intensity of an afternoon storm. For another, your goal could be to convey the quiet stillness of a mountain sunrise. To think that both of these scenarios require the same composition — even assuming that you’re at the same landscape — overlooks the purpose of composition in the first place: to convey your chosen message to a viewer.

A better rule is simple: Compose every photo so that it looks how you want. First, define your goal for the photo. Then, take the elements in a scene that matter the most, and emphasize them however you see fit in order to meet that goal. Walk forward and backward; move your camera up, down, and sideways. Choose your technical settings and camera equipment in a way that advances the creative message you’re trying to get across. After that, just take the photo.

No rule of thirds, no problem.

2. Take a Lot of Photos

Henri Cartier-Bresson famously said, “Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst.” He was a street photographer, but it’s also true for landscape photography. As redundant as it sounds, taking photos is the best way to take better photos. Spend as much time as possible behind the camera.

That’s not all that matters, of course. It’s also crucial to look at your best images, and then ask yourself questions. What makes them work so well, and would you do anything differently next time? Make a mental note of everything you can. That’s even true for your bad photos — they are perhaps the best tool at your disposal for learning where you can improve the most.

If many of your photos are either too bright or too dark, you should work more on your exposure skills. If you aren’t capturing quite the sharpness that you want, figure out what needs fixing. Or, if you’ve mastered all that, but your landscape photos just don’t have enough of an emotional impact, you need to pay more attention to light, subject, and composition.

I take as many photos as possible every year. All of this practice adds up, and, over time, it’s easy to see some of the areas where I’ve improved (and what I still can do better). Quite simply, your work will get stronger and stronger as you keep taking pictures. This is one of my favorite landscape photography tips, since it’s something you’re already doing. Yet, it’s still one of the most powerful ways to improve.

3. Ruthlessly Critique

Not only should you take a lot of photos, but you need to be critical of the photos that you take. This isn’t always fun or easy, but it’s how you recognize your mistakes and keep improving.

Even if I’m planning to delete a photo, I always take a few seconds to study it carefully. I ask myself why I’m deleting it. The goal is to avoid making the same mistake again. Of course, it can be very difficult to critique your own photos. Even if you want to be critical, it isn’t always possible. Sometimes, when the backstory of a particular landscape photo is still fresh on your mind, it isn’t possible to see things as objectively as you may want.

What do I mean by that? Imagine that you spent a full day hiking up a mountain, then camped overnight and took a photo of the Milky Way. It may not be one of your all-time best photos, but it feels like it should be. After all, it was incredibly difficult to take!

When you’re sorting through your photos later, that Milky Way photo will pop out, simply because you remember all the difficulties of capturing it. I know from experience — it’s impossible to give photos like that an accurate review. Maybe they’re great, and maybe they’re not. But if the experience is still clouding your thoughts, it can be very difficult to tell.

For a while after taking this photo, I couldn’t decide how much I liked it. The problem is that it was a beautiful and difficult hike, and my memory was too fresh for me to form an accurate critique. Two months after the fact, I can see things much more clearly — and I can tell that, although I do like the photo, it doesn’t have a clear enough message (or subject) for me to consider it a top image.

The best thing you can do is to wait until your emotions from capturing the photo have started to subside. This can take anywhere from a few days to a few months. The longer you wait, though, the easier it is to see photos for their own merits.

Or, you could show your work to another photographer. Posting them online isn’t always ideal — especially on apps like Instagram — but many people enjoy sharing their work on dedicated photography forums. Of course, you also can talk to photographers who you already know and get their opinions as well. Either way, it can help to hear a third-party critique of your photo; you might see things that you didn’t notice at first.

You don’t have to do any of this if it doesn’t sound appealing. What matters, instead, is that you come up with a way to look specifically for issues with your work, including some of your best photos. It can be a harsh process, but it’s also the best way to avoid repeating a simple mistake in the future. For many people, that’s an important goal — continuing to improve your work and your abilities over time.

4. Bring a Tripod

Everywhere you go, bring along a tripod.

For a landscape photographer, this is perhaps the most important piece of equipment you can own. Tripods improve the image quality of every photo you take. They stabilize your camera and let you take long-exposure photos once it gets dark, providing the best image quality that your camera can offer.

It’s simple: if you plan to take landscape photos, you should carry a tripod. I always do, whether I’m taking pictures in my backyard or on a long hike through the mountains. No, tripods aren’t fun to use; they’re heavy and expensive. Still, they are a vital part of landscape photography, and you should carry one even if you’re trying to go lightweight.

Which tripod should you get? That all depends upon your budget. Eventually, if you stick with landscape photography, you’ll probably want a good carbon fiber tripod. They’re the best combination of study and lightweight, but also very expensive. Until then, get one that works (but doesn’t break the bank), and don’t replace it until you’re ready to upgrade to your dream tripod.

Especially when you’re starting out, the specific tripod isn’t all that important. A basic tripod will have some significant issues, but even it is a thousand times better than nothing. Get in the habit of using one, and you’ll know soon enough whether it’s worth getting a high-end model down the road.

And, as much as you might hate carrying it around at first, you’ll grow to love your tripod. Personally, I’m at the point where it feels strange to take a photo without one. The tripod has become a part of my thought process — a starting point that makes every other part of photography far easier and more natural.

5. Know Your Camera

Usually, landscape photography is very slow-paced, and the scene in front of you doesn’t move much at all.

Sometimes, though, you’ll end up photographing a crazy storm that’s breaking overhead, or a beam of light that lands for half a second in the perfect position. You’ll see an amazing breaking wave, or a spectacular explosion of lava, or a rainbow fading in the distance. Landscapes move slowly, until they move really quickly all at once.

When that moment happens — and it’s always unexpected — you need to be ready. Most importantly, you need to know your camera. You need to know how to use it blindfolded, and you need the skills to choose the right settings as quickly as possible. The less time you spend fumbling with your camera, the more time you can spend composing your photos and capturing the shot you have in mind.

How often will you find yourself in these types of situations? Personally, I find that amazing, unexpected events like this happen only a few times every year. It isn’t common at all. But, if you can make the most of fast-changing landscapes, you’ll end up with some of your best photos.

I only had seconds to capture this photo. The rainbow was fading, and I didn’t have time to do anything but compose and shoot. If I had spent more than a few seconds on camera settings, there’s no way I would have captured this photograph.

You won’t always react quickly enough to get every shot you want, and the photos you miss will haunt you. I can think of several photographs, for me, that are the “ones that got away.” Even though I know how to set my camera and use it quickly, I miss about a third of photos in fast-moving situations like this. I’m trying to get that figure down to 0%, and, until I do, there’s always room to improve.

Every time that you take landscape photos, you should have a plan in case something crazy starts to happen. Do you know what exposure mode you’ll use? Have you practiced changing lenses quickly (and without dropping them)? These are basic things that take too much time for many photographers, and they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

Again, this is something that takes practice, but it also takes the right mindset. If you’re always ready to jump into action, you’ll capture the shot that everyone else missed. The better you know your camera, the fewer opportunities that will slip away.

Conclusion

Good landscape photography tips can be hard to find, and it’s true that these are all just quick suggestions. Still, my hope is that you’ll find some of them useful and be inspired to use them in your own photography. Also, if you feel like you’ve mastered these tips, and you’re ready to take things another step farther, you might also want to read my article on advanced landscape photography tips.

Landscape photography is wonderfully fun, and it’s even better when you actually end up capturing the image you had in mind. These tips are a good place to start, and, even if you just focus on one of them, my hope is that you’ll see the quality of your landscape photos improve. No matter what, though, especially if you’re just starting out in landscape photography, I have no doubt that many exciting experiences await you in the future.

Spencer, I cannot agree with you about using a carbon fiber tripod. I have a fairly expensive “heavy duty” carbon fiber, but never use it as I prefer an “old school” Manfrotto 190D with the #029 MK2 tripod head. It is all aluminum, heavy duty, and well made. And, I have two different center columns for it, a shorty and the standard. It weighs 4.0 kg or 8.8 lbs. Add the weight of the Nikon D3, D3x, or D3S with lens and it it rock solid. I have been known to add a weight bag to it.

I paid a pretty penny for the “heavy duty” carbon fiber, but found the Manfrotto 190D with its #029 MK2 tripod head unloved and unwanted, for $99 in a second hand camping gear shop window. The head was jammed in the fore/aft tilt direction, but I simply disassembled everything, cleaned it up, and have happily used it for many years, since -and, never wished I had brought my carbon fiber with me, instead.

If I am shooting single frame astrophotography or landscape, with up to 1000mm focal length, I will use another Manfrotto 161 MK2B with a 400N Geared Head. It is ideally suited for studio work, due to size and weight. It weighs 10.6 kg or 23.369 lbs.

I have been taking photos, since 1967 and internationally published/paid, since 1992. So, not a novice.

A rock solid tripod is absolutely essential for serious photography.

A rock solid tripod is essential, I agree. Aluminum isn’t inherently bad either. All I’m saying is that, for a given tripod weight, carbon fiber is simply more rigid – it is a matter of physics. Your 4kg aluminum tripod is probably super stable, let alone your 10.6kg tripod. But the same could be said of a 4kg or 10.6kg tripod make of carbon fiber! It’s the weight that makes it stable.

Re the tripod, I gave been told by several landscape and architectural photographers that a monopod works just as well, is less obtrusive, and is easier to lug around.

Hi Jeremy, not sure who told that to you, but I wouldn’t take their advice. A monopod eliminates motion on the vertical axis, and decreases it somewhat on the horizontal and yaw axes. A tripod eliminates motion on every axis. You can easily use shutter speeds of 5, 10, 30, or 1000+ seconds on a tripod without motion blur. A monopod is capped around 1 second if you have good technique, and even then, an equivalent photo from a tripod will be sharper on fine details.

Not that there isn’t a place for monopods. A lot of architectural photographers like them because most interiors don’t *need* more than about a 1 second shutter speed, and it’s certainly true that they’re less obtrusive and easier to carry. But to say that a monopod works just as well as a tripod is very, very far from the truth.

When we do learn a new language people often say: Start to talk, then you will quickly learn. It’s the same with photography-the language of light. As more photos you take you will understand the principles, words and forms to understand and speak that language. Light has many faces, learn to see it. Doesn’t matter what you shoot. Composition is the framework it will come with every shot you take.

I mean to see good quality of light, shadows, a perfect composition you actually don’t need a camera, you can do this with your eye. Go take a walk with your dog and lookout for the good light, the decisive moment, the perfect composition. Practice while waiting for the bus. Or sitting in the park or…whenever, wherever.

Spencer,

I am just getting into landscape photography and I found this article to be quite helpful, especially the

other articles that were attached. I already have a Nikon D750 that I use for some of my wildlife shots, so

I think I am good there. For lens, I have a Nikon 16-35 F4 along with a Nikon 24mm, 50mm, 85mm and a

70-200 f2.8. I have a very good tripod. Now all I need is to learn how to use the equipment.

Thanks for posting these Great helpful articles.

Sherman

Hi,

I’ve been Reading this with high interrest. You are right in many points, but the last photo of the ‘no rules’ section should not be titled ‘no rule of thirds, no problem’. Have auch second closer Look, there ist a lot of ‘ rule of thirds’ ;)

Regards, Joeran

PS: All your articles to date are outstanding!

Sorry for german auto-correct, i wanted to say:

Have a second closer look, there is a lot of ‘ Rules of Thirds’ in it.

— Joeran

Error: I’ve been using the 20 pounder since 1996, not 1986. Errors like this drive me bonkers, even if they don’t affect the main point.

Excellent article! You are correct about tripods in landscape shots. Two points.

1. Tripods do more than steady your camera. They allow you to make fine adjustments to your shot, tiny improvements in composition. You can stare at the scene, and then make an adjustment every once in a while as you refine your concept. You can use whatever aperture or shutter speed your composition needs; you can ignore these instead of working around them. You can stand there and wait for the sky to change, knowing that you’ll be perfectly composed, exposed, and filtered when it does.

2. Weight is your friend. In bad conditions — high winds, springy grass, etc — weight is the only thing that works. Since 1986 I’ve been using a set-up that tops 20 pounds with a 35mm camera mounted, and I sneer at 15mph Oregon Coast winds. I also have a good light-weight Gitzo for far-away-from-the-car, and I can tell you it does not cut the mustard. I’ve recently switched back to the 20 pounder on every shot, and put up with sore shoulders.

Very true points! I didn’t go into it as much above, but for me the compositional side of using a tripod is at least as important as the image quality side. Being able to replicate the same composition as conditions improve, or to make small adjustments to your framing without issue, is a benefit that can’t be overstated.

As for weight, a 20-pound setup is incredible. I can’t say my tripod is as heavy as that, but I’m sure it’s also not as stable! It does worry me to see beginning photographers using five-section MeFoto tripods at full height, including the center column, when it isn’t absolutely essential for composing an image. Even with my full RRS kit, I try to keep the tripod’s thinnest leg sections collapsed whenever possible, particularly with my telephoto. That, too, isn’t enough to stop camera shake in windy conditions. Perhaps a 20-pound monster is in my future :)

Regarding #3 when I was a student in professional photographic illustration @ RIT a professor had a good solution…print any photograph (especially those you are not sure you like) and display them so that you will see the image(s) daily. After about two weeks your thoughts about the images will change. This really works and today instead of printing, maybe make the image a screensaver or use a digital frame.

That is a clever and useful tip! Sometimes, you’ll notice things in a print that stand out more than in the digital image. So, I do think there is a benefit to having a hard copy for this sort of thing, although a screensaver would be another good way to keep seeing the image over time.

Thank you Spencer for this very informative article. Going to check out your site!!!!!

Much appreciated, Kelly, glad that you liked it!

The term “rules” is indeed a misnomer when it comes to composition. Most are derived from analyzing the works of the masters of photography and painting. So ignoring them is only a good advise for those who have the innate eye for composition, and for those who have mastered the art of composition. To master composition (if that is even possible), one has to get acquainted with them, apply them, and analyze the results to determined if their use was good or not, and why.

One resource I have found most beneficial, for studying composition, is Ian Plant’s “Visual Flow” book. I highly recommend it.

It is fair to say that some “rules” come from high-level artists — especially things like balance, visual weight, structure, interrelationships, patterns, and so on. To me, these are different from things like the rule of thirds, since they are not static or concrete. They allow much more flexibility to tell your message without “violating” the rules — and I would argue that they are indeed the building blocks to tell your message in the first place. Thanks for adding this!