Last week, there was rain in the desert. I was so surprised to visit some of the driest places in America – Death Valley, Joshua Tree, Canyonlands, and more – and see them under storms and fog rather than the blue sky. It’s not “good weather” by most definitions, but it was perfect for landscape photography.

Bad weather makes good photos. It’s a mantra that I repeat to myself any time I feel the raindrops start to fall. The atmosphere of rain, snow, fog, wind, and other uncomfortable conditions can tell a story that good weather never could.

Of course, you can also take beautiful photos on a sunny day. I love photographing backlit trees and other intimate landscapes in the sunshine, and nothing beats Milky Way photography on a clear night. But bad weather is in a category of its own.

Chiaroscuro and the Spotlight Effect

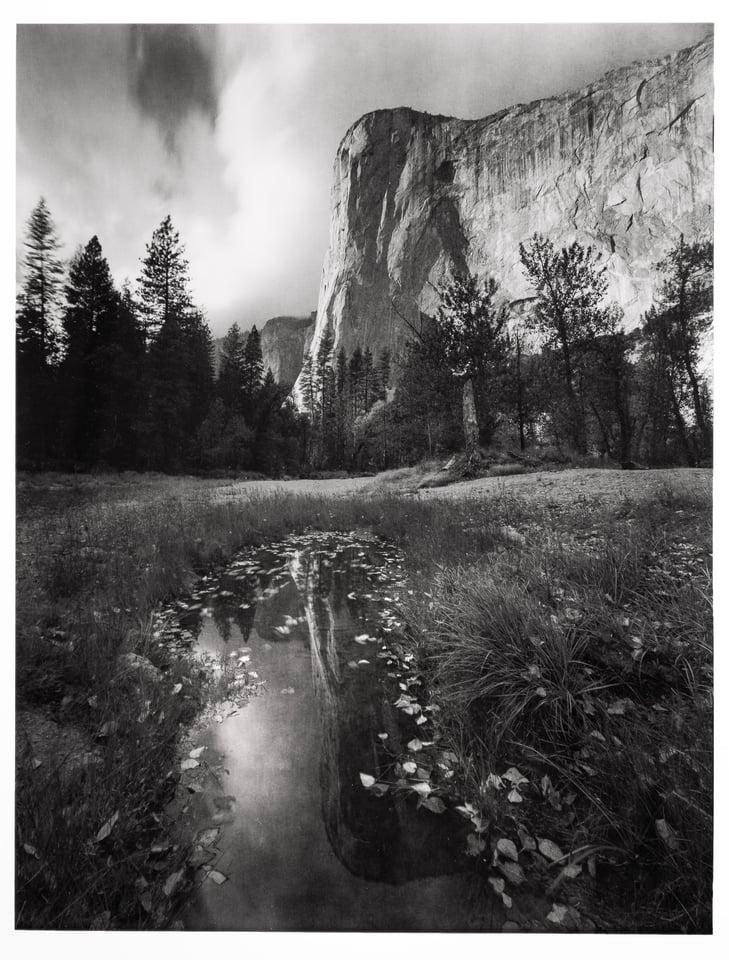

The best part of bad weather is the light, which has endless variety and character. One of my favorite examples is the “spotlight effect” – because even in a storm, there are often gaps in the clouds where sunlight shines through. This can selectively illuminate parts of the landscape and the sky itself in fascinating ways. It’s related to the topic of chiaroscuro that I wrote about last year.

Another example of the spotlight effect is lightning. This one is definitely more dangerous, but you can read our guide to photographing lightning if you want to know how to take photos like this. The portion of your photo illuminated by lightning immediately becomes an eye-catching, high-contrast subject with hints of chiaroscuro.

Sometimes, if the bad weather is moving in from one particular direction, the sun will keep illuminating the landscape in front of you while there are dark clouds overhead. Normally, we’d expect the sky to be brighter than the landscape, and this flips things on their head! It’s enough to make a photo stand out. One of my rules in landscape photography is to pull out my camera whenever I see this type of light.

These are just some of the many examples of good light in bad weather.

Sandstorms, Rainbows, and Blizzards, Oh My!

“If you want to be a better photographer, stand in front of more interesting stuff.”

You can thank National Geographic photographer Jim Richard for that quote, which is one of my favorites. If you think back to the best photos you’ve ever taken, it’s probably true – your subject is interesting and tells a story.

Bad weather is interesting. If a sandstorm hits while you’re taking pictures on the sand dunes, that’s a great story, and I can think of a thousand other examples. Blizzards, lightning, dust devils, frost, rainbows – they’re probably not going to happen on a calm day when it’s 65° and sunny. (18° for my Celsius readers.)

To use Jim Richard’s language, bad weather is “more interesting stuff.” There’s a reason why some of the most extreme places on the planet, Death Valley to the Himalayas, are so good for photography – in places like that, it’s easy to see the story of how the weather shapes the landscape.

Colors and Simplicity

It might look like I took the following photo in good weather, but a second glance at the colors of the scene will hint at something more. In fact, I took this photo at Crater Lake in 2021 when a bad wildfire was nearby. The air quality was terrible, however, for photography, the haze added a stunning pastel atmosphere that would not have been possible in nicer conditions.

We often think of bad weather as chaotic, but in the case above, it was a way to help simplify my photo. This isn’t uncommon in bad weather. For instance, distant sunlight could backlight the rain, making your whole photo glow yellow and orange. Or, the storm clouds could be so thick that the entire landscape turns into deep, blue tones. Then there are the obvious examples of fog and dust storms, which simplify your photo by obscuring most of the details in the background. (You can see examples of all three of these situations below.)

Bad weather doesn’t always simplify your photo and unify the colors in the scene. Just as often, you’ll get the “spotlight effect” again, where part of the landscape is glowing while the rest is deep in shadow. It all depends on the scene and, of course, the direction you point your lens. But if the conditions are right – meaning that the weather is bad! – look for opportunities to simplify your emotional message and capture more effective photos.

Conclusion

I hope this article gave you a sense of why bad weather can be such a delight in landscape photography. How do you make the most of bad weather when it happens? My answer is simple: if the conditions are safe, just stay outside.

Staying outside in bad weather reminds me of another unloved part of landscape photography – waking up early for sunrise. Uncomfortable? Yes, it can be. Worthwhile? Absolutely. Too many photographers pack their bags once it starts to rain, and they miss some of the best light and subjects on earth.

Personally, if I got rid of every photo I took in bad weather, I think my portfolio would be about half the size. That holds true with my cityscape and macro photography as well! Outside of photography, I love sunny days. But when there’s a camera in my hand, give me raindrops over cloudless days almost every time.

In short, bad weather makes good photos – at least when you combine it with some creativity on your end. So, throw on the spare poncho that’s in your backpack (add one if you haven’t already!) and tell yourself to stick around a bit longer. You’ll be glad you did.

This article was not helpful. I’m waiting for one titled “Solid Overcast For 89 Days and Counting Makes Good Photos!” 😝

I have no idea what this “good light” is that people talk about.

Good light is a lot rarer than bad light. I’ve found that there are three good options when it’s that overcast.

One is to photograph smaller subjects and intimate landscapes that don’t need sunlight or sky in the photo. Forests are perfect for this.

Two is to make your own light. Portrait photography and macro photography work well on cloudy days, since you don’t have to account for harsh sunlight on your subject. You can be more flexible with your flash and lighting setup.

Three is to shoot at blue hour. Overcast blue hour looks great – very moody and intense. I often like blue hour more than golden hour anyway.

“I often like blue hour more than golden hour anyway”

PREACH! I have the same thoughts.

Yeah, it was a wry joke about the crap conditions we have here – for the benefit of others in the same boat. All the vegetation is dry, brown and dead. All the animal life is hibernating or has migrated. We see the sun about once a month the rest of the time it’s just gray.

Still, my whole reason for taking pictures is that it makes me get out, open my eyes and actively LOOK for subjects and I tell myself to work with what’s in front of me…but this time of year, it’s a real challenge.

I could tell you were kidding, but it was still a great point! We’re not going to have good light all the time, or even most of the time. It’s important to keep going out and taking pictures anyway.

We don’t even have Blue Hour -it’s Dark Gray hour. 😉

Agree wholeheartedly with the thoughts in the article but….sandstorms are fine if they are some distance away! I just choose to not risk sand getting into every crevice of my Z6. What do others do in this situation? Do you use something protective, or pack the camera away?

I found the Z cameras to be quite resilient when it comes to sand. I only used the 24-200 to avoid change lenses though.

What I’ve done:

1) Use only weather sealed lenses

2) Do not change lenses

3) Thoroughly clean everything off after I get back home, taking special care around anything that moves (especially telescoping barrels, buttons, knobs, etc.)

But that’s just when it’s windy in sand dunes, not when it’s a full blown sandstorm. If we’re talking color run or Burning Man or abuse of that kind I’m just not going to bring the camera. Or maybe it’s time to invest in an underwater housing.

U.K. photographer Martin Parr’s first book was called ‘Bad weather’ (it is more people than landscapes, but the one of Yorkshire mill town Hebden Bridge is a gem (it’s also photographed by Fay Godwin)).

I lost my copy in our 2007 floods …

I see you use a Viltrox lens. How do you find it?

I enjoyed it! I was testing two (the 24mm and 35mm AF lenses) for upcoming reviews. It strikes me as a good balance of price and features, although the Nikon Z 24mm f/1.8 is certainly better optically.

The lightning in the swirl in the clouds makes for an almost alien scene. Nice!

That said, I suppose ‘interesting’ is very dependent on the intended use. For personal projects, or photo’s for photography’s sake so-called bad weather can definitely make for unique or otherwise unusual scenes that elevate a location – or even tell a story if the photographer finds the right angle.

But for many of the clients I’ve worked for, I’m pretty sure that the only place they’d ever want to see a raindrop on a photo is alongside an obligatory ‘we advise visitors to prepare for the weather in winter’ note on their website or in their brochure. Clouds are generally fine, though, and can be a big help in how they change the light in the scene. Anything ‘worse’ means the attempt is usually scrapped. For that purpose, anyway.

Thank you, David! And good points. I would never hope for stormy weather if I were making a brochure for Hawaiian travel :)

It shows that the client’s or viewer’s perspective always plays a role in how our photos are interpreted, whether we like it or not.

Great photos, Spencer. The best “spotlight” effect I’ve ever seen was years ago in the White Mountains of California, looking toward the Sierras. Unfortunately I didn’t have my (film) camera out, but I still remember the scene. Question: how do you meter (in camera) for the spotlight scenes? Will Matrix metering cover it?

At least on Nikon, matrix metering biases too much toward the focus point. It’s not foolproof in spotlight situations. Even though I still use matrix, I’m also using exposure compensation in one direction or the other. I always keep an eye on the histogram (usually the three-channel histogram when reviewing photos) and expose as bright as possible while carefully avoiding clipping.

This reminds me of a moment in time at Singapore where a group of us were scouting around for interesting perspectives to shoot from, and we just happened to come across an incredible sight of a heavy thunderstorm rolling in towards the city.

It was a sight to behold, with the heavy clouds being a sharp contrast to the sunny portions that were rapidly being smothered, with whatever light that was left showing off a literal wall of rain pouring down the city.

It was spectacular.

Wow, that’s awesome. I can picture it vividly already based on your description. There are a few moments like this which we will never forget as photographers!

Nice article! I have been to many of the desert locations you list in the introduction, and indeed, the cloudless skies were a bit of a problem. :D At least I got treated to a good old-fashioned sand storm in Death Valley during my last visit, which created some interesting opportunities.

They are some beautiful places! I’ve been lucky to see a couple of storms in Death Valley before, but usually when I visit the desert, it reminds me why it’s a desert.

+1!

We’re really not taking pictures of objects, we’re taking pictures of the light that reflects off them. And IMHO there’s no light like that shaped by clouds. The shadows make compositional elements. The varying intensity creates depth. And the selective attenuation affects colors in interesting ways, forget about white balance. Good article…

Thank you, Glenn! Whether the weather is nice or not, I always hope for clouds for my landscapes. When I went to Yosemite last year and had sunny skies for a couple of weeks, I had to change course and shoot a lot of forest photography and intimate landscapes that didn’t need the clouds. Fun in its own right, though.